Loy’s playwriting coincides with her literary debut, first in Camera Work in 1914 with “Aphorisms on Futurism” and followed by publications in Trend, Rogue, Others, The Blind Man, and The Dial. Once settled in New York, she starred with William Carlos Williams in Alfred Kreymborg’s Lima Beans, a one-act play produced by the Provincetown Players in December 1916.

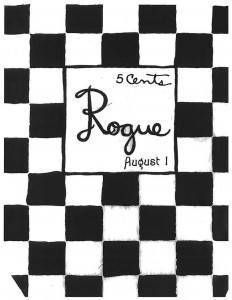

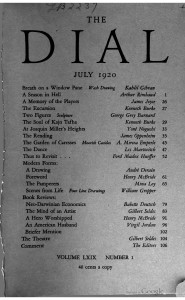

Three of Loy’s plays were published in New York-based little magazines. “Collision” and “Cittàbapini” appeared under the title Two Plays in the August 1915 Rogue, and “Cittàbapini” was republished on its own in the December 1916 Rogue. The Pamperers appeared in the July 1920 Dial, introduced by art critic Henry McBride to inaugurate a “Modern Forms” section “devoted to exposition and consideration of the less traditional types of art” (61). Loy tried to find a home for The Sacred Prostitute, but the play remained unpublished until 2011, when it appeared in print in Sara Crangle’s edition of the Stories and Essays of Mina Loy and online in Triple Canopy.1

Little Magazines as Stages

Although the plays were not produced in Loy’s lifetime, little magazines served as stages for experimental literary productions, connecting them to real live audiences. Little magazines—small, non-commercial, often short-lived forums for alternative ideas and forms—function as experimental performance spaces, more similar to theaters than to books. As I’ve argued elsewhere,

Little magazines are intimate and social: they bring together an ensemble of writers into a small space, staging a performance for a familiar audience of like-minded people, who read each issue during the same limited time period. The sense of time, space, and audience is palpable in little magazines, which often prominently feature the life world of the magazine—the editorial work, the production tasks, and the conversations among contributors and readers. Margaret Anderson, for example, frequently comments on the work of publishing The Little Review, going so far as to publish a series of cartoons illustrating her activities when she was not working on the magazine because acceptable contributors had neglected to come forth. The cartoons insist upon the need for an ensemble of willing participants to bring about a successful little magazine production. The motto of Poetry—“To have great poetry, there must be great audiences”—attests to the necessity of an audience to understand and appreciate the performances staged within a little magazine.2

The correspondences between little magazines and experimental theaters can be seen in the striking resemblance between the cover of Rogue and black and white checkerboard set of “Lima Beans,” designed by Marguerite and William Zorach based on screens by Gordon Craig (Kreymborg 243).

The same artists and aesthetics transferred from one forum to another, insuring an understanding, appreciative audience for literary and dramatic productions.

Rogue, the decadent, irreverent, “cigarette of literature,” presented Loy’s Two Plays to a small coterie audience of avant-garde artists, wealthy patrons, and Greenwich Village bohemians who were open to experiment and receptive to off-beat humor. The Dial, a more prestigious, serious magazine of the arts, allowed her work to reach a wider audience of intelligentsia, elevating her to a stage she shared with Arthur Rimbaud, James Joyce, and Ford Maddox Hueffer.

-

Archival versions of the four plays are now available in PDF form for viewing and downloading in the Beinecke Library’s digital collection:

Scholarly reprints of The Sacred Prostitute and The Pamperers are available, somewhat surreptitiously, in Stories and Essays of Mina Loy, astutely edited by Sara Crangle (Champaign, Dublin, London: Dalkey Archive Press, 2011). A delightfully illustrated version of The Sacred Prostitute is also available online in Triple Canopy.

- Suzanne W. Churchill, “The Lying Game: Others and the Great Spectric Hoax of 1917,” in Little Magazines and Modernism: new approaches, Eds. Suzanne Churchill and Adam McKible, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing 2007, p. 179.