A Burlesque of Love & Sex

According to Sara Crangle, Loy wrote The Sacred Prostitute in 1914 while living in Florence, as a burlesque of the battles between the sexes she witnessed and experienced in her affairs with the Futurists.1 The play was never published or performed in Loy’s lifetime, but Crangle pieces together the handwritten and typed manuscripts to reveal a hilarious send up of the sex wars. As in Two Plays, Loy deploys an eclectic method, but in Sacred Prostitute, she combines avant-garde techniques with allegorical forms to expose gender as a performance, love as a game that women can’t win, and the sex war as a commercial enterprise from which no one—not even the Futurist—escapes.

The title, The Sacred Prostitute, deconstructs the division between virgin and whore; as Loy puts in her “Feminist Manifesto“:

The first illusion it is to your interest to demolish is the

division of women into two classes the mistress,

& the mother

For Loy, the realm of the sacred is inseparable from the profane: both are entangled in the same sexual economy in which women exchange virginity for wealth, security, and male protection. Love is the illusion and marriage is the contract that together render the prostitute sacred in the eyes of society.

Were it staged, The Sacred Prostitute has the potential to be brilliant and funny satire of sexual relations, yet it could easily become boring and talky. The characters are types, some even seem interchangeable, and stage directions do not indicate a distinct physical setting: the characters’ performances—their gestures, postures, and poses could take place anywhere and everywhere. One way to highlight the theatricality of the characters’ poses and maximize audience participation would be to stage the play in a marketplace, mall, or plaza. In such a setting, the line between players and audience members could blur, exposing their mutual investment in the same entertainment economy.

Read the play in Triple Canopy

Plot Summary

The play opens with a group of men debating the value and appeal of women. Futurism arrives on the scene, first dazzling the men and then seducing the women. But when Futurism meets Love—a woman like no other he’s “had” before—he finds himself faced with a new challenge. He attacks her publicly, tries to seduce her privately, and then enlists her in a boxing match—a Futurist restaging of the Sex War—for the benefit of Don Juan, who wants to learn some new tactics in the game of love. After three rounds, the cutting-edge fight degenerates into familiar, predictable moves. The Procuress of the World and her associates appear on stage, revealing that the entire spectacle has been a mass commercial scheme.

The Theater of Spectacle & Performance of Gender

In The Sacred Prostitute, Loy casts Futurism and Love as allegorical figures in order to investigate on an intimate scale whether she and Papini can achieve a harmonious relationship, and on a grand scale, whether men and women can form mutual, loving partnerships. Although the play comically satirizes the “sex war,” it also seriously examines spectacle. The meta-theatrical comedy looks at looking, making a spectacle in order to scrutinize the making of a spectacle. Loy upstages male Futurist performance, spotlighting his postures, poses, and ruses before various audiences. In the process, the play exposes gender as performance—one that comes with a prefabricated script and is highly dependent on an audience.

As in her previous micro-plays Collision and Cittàbapini, Loy continues to explore en dehors garde strategies for exploring gender as performance and collaborating with her audience. In Sacred Prostitute she also makes an en dehors turn outward to the public in order to scrutinize intimate relationships. Loy looks skeptically and humorously at a boxing match initiated by the futurist avant-garde, exposing how the politics of gender, romance, and “bromance” become entangled in the ring.

The play opens in an indeterminate setting, possibly a café or salon, with “a rogue’s gallery of male ‘types’” discussing “the problem of love” and debating strategies for seducing women.2 Loy’s choice to begin in medias res implies that the misogynist discourse is ongoing and continuous. Indeed, the timeless discourse constitutes both the setting and characters in the play, appearing at the top of the manuscript, where we would expect to find a set description and cast of characters.

Interrupting the dialogue, Futurism arrives on the scene “with a loud report,” determined to stir things up and demonstrate some new tactics. He enthralls his all-male audience by conjuring an illusion of the future with his bare hands. “A prophet has come among us!” the Men ejaculate, their exclamation an expression of homosocial desire. The Procuress exclaims, “My word—the women ought to see this!” She summons women onto the stage, and Futurism promptly “lascivates” them with his eyes, leaving them begging to sign their names in his autograph album, “a tome labeled ‘Women I have had.’”

Dryly observing that Futurism has “successfully plumbed the feminine shallows,” Dolores, the only named woman in the play, offers him a greater challenge, introducing him to Love, a character with a “hermaphroditic aspect,” who is immediately unhooded and exposed as a beautiful woman with golden curls. “For the benefit of his male audience, ‘Futurism’ manhandles Love,” Janet Lyon observes, “but when his audience leaves (not wanting to witness another man’s triumphs),” he grows gentle and apologizes, saying, “Excuse me, I hope I didn’t hurt you. I have to do that for the sake of my reputation.”

Futurism’s confession exposes masculinity as a homosocial public performance, in which men dominate women to impress other men. Heterosexual romance operates in service of homosocial “bromance.” But even after the men and women leave the stage so that Futurism and Love can exchange private intimacies, Loy makes it clear that they are still play-acting in the “game of love”—another game that women can’t win. After an exchange of verbal sparring and seductive sallies, Futurism declares “check-mate” and stuffs Love into his pocket. In Sacred Prostitute, Loy’s en dehors garde staging illustrates the necessity to re-stage the steps and directions of gender performance. Even if, as a female playwright, she can’t extricate herself from mandatory gender scripts, she can at least try to outwit them.

Staging a Feminist Critique

In both public and in private, Futurism—exemplifying masculine performance—attempts to delude, outwit, seduce, and triumph over an audience presumed to be feminine, inferior, and pliable. Loy orients performance in a different way in her play, however, and staging is key to her en dehors garde critique.

The scene in which Futurism stuffs Love into his pocket offers a case in point. At first glance, it seems impossible to stage, but clever designs for costumes and set could conjure the theatrical illusions Loy imagines. Stage directions indicate that Love is wearing “a formless roseate garment,” and her gown could have a detachable scarf that Futurism pulls off as he picks her up. He could stuff the scarf into his breast pocket as the actress slips away behind a curtain. If the stage had a roseate curtain for the backdrop that Love first emerged from, the set would make visible the way in which women serve as audiences for male performance and are indistinguishable from the domestic spaces that define their roles and limit their orbits.

This beat is an important allegorical moment in the play, which literalizes female objectification. When Love is put in a man’s pocket, like a wallet, she is reduced to a commodity that can be exchanged in a male dominated economy. “What have you done with her,” the men ask Futurism, who “(absent-mindedly)” replies, “Oh, everything—and nothing,” indicating her reduction in value. Although Loy can’t evade female objectification, she can analyze it, put it on view for our scrutiny, and expose a hidden or underlying truth about gender inequality. In this way, she deploys an en dehors garde strategy of unveiling the workings of a system that commodifies and marginalizes her as a woman.

Amateur Theatricals

Just after this beat, the Procuress reappears to announce, “We are just going to have some amateur theatricals—if you care to stop?” Futurism, already engaged in his own amateur theatricals, doesn’t get the joke and just keeps performing. The Procuress introduces a play called “Man and Woman,” and stage directions indicate: “(The audience sit circlewise on the outskirts of the hall to watch the performance.)” We do not get to see the theatricals, however, because the next page of the manuscript indicates: “Seven pages of manuscript missing.” This omission may not be an accident, however, because at this crucial turn, the actors are converted into an audience, and their reactions to the “amateur theatricals” become the spectacle we watch.

This turn is similar to one used by Charlie Chaplin in his 1915 silent film, A Night at the Show. Chaplin plays two characters in the drama, the highbrow Mr. Pest and the lowbrow Mr. Rowdy (in the gallery) and both are audience members for the eponymous show. Their behaviors and antics as audience members become the spectacle we watch, as in this scene:3

View this film at Public Domain Movies, starting at 9:12.

The two men holding hands over the lovely women between them could be Don Juan and Futurism, comically interacting while a play goes on in front of them. But whereas Chaplin shifts the camera among highbrow theater-goers in the dress circle and boxes, lowbrow audience members in the upper balcony, and scenes from the Orientalist theatrical, “La Belle Weinerwurst,” in Sacred Prostitute, Loy limits our attention to the antics of the highbrow characters gathered to view the amateur theatricals. At this moment, she’s more interested in satirizing the antics of the avant-garde than in poking fun at audiences.

Boxed into the Sex War

Unable to watch “Man and Woman,” our attention turns to the side show of Futurism and Don Juan. Bored by a performance that doesn’t include them, they plot to induce Nature to destroy women and allow men to self-propagate. When Nature rejects their idea, Futurism suggests that they turn their backs on her and “identify ourselves with machinery!” But Don Juan feels stronger comparing himself to women than to machines, so he asks to “hear some more about the latest amorous strategics.”

Futurism agrees to perform, and the stage directions indicate how Love’s feminine identity is conjured by his “off-hand gesture” (masculine sleight of hand) and “masterful eye” (male gaze):

(with an off-hand gesture he draws love out of his pocket, scattering the newspapers, shakes Love out and stands her on the floor in front of him, taking her measure with a masterful eye as she pulls herself together.)

He announces, “This is the sex-war,” and conscripts Love into the role of his co-star: “Come along—you must pretend anyway,” he tells her, “Somebody’s probably looking.” Once again, gender is exposed as a performance, staged for the benefit of an audience.

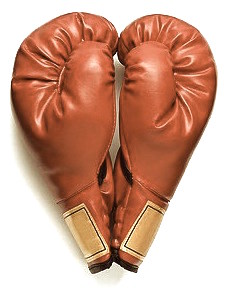

The couple don heart-shaped, red flannel boxing gloves and begin sparring. Although Loy hadn’t yet met Arthur Cravan when she wrote the play, the scene of Futurism sparring with Love might resemble this film clip of Cravan sparring in a 1916 match in Barcelona:4

Thirty seconds into this film, Cravan spars with a much smaller contender, who lashes wildly against his giant opponent. The little guy could be the plucky, unfaltering Love trying to break down Futurism’s towering, muscular ego.

Whereas the sturdy Cravan has no need to vary his boxing technique, in the Sacred Prostitute, the match extends for three rounds, with tactics shifting in each:

- Round 1: Violent Conquest, in which Futurism battles Love and wins a kiss, returning it with a punch and a caress.

- Round 2: Romantic Seduction, in which Futurism lures Love into a hypnotic state, until she snaps to her senses and remembers his misogyny; ends in draw.

- Round 3: Sexual Awakening, in which Futurism excites Love’s primal instincts and she becomes territorial, driven by violent jealousy to protect her future offspring.

The boxing match comes to a halt when the players realize that the “latest amourous strategics” are nothing but an “elementary old-fashioned fool’s game.” The match is just another round of the same primitive battle of the sexes that’s gone on for centuries. Directing the players to repeat stock “strategics” that end in a draw, Loy’s play deploys innovative, en dehors garde strategies that wittily re-stage the predictable steps and enable the audience to recognize the patterns.

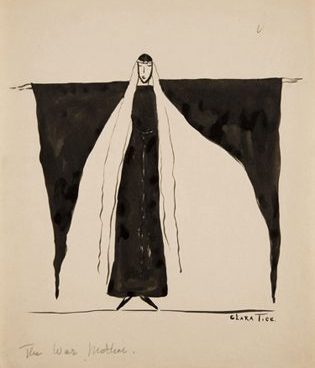

Epilogue: The World’s Brothel

In an ironic epilogue, the Procuress reappears on stage, accompanied by the Directors of the World’s Brothel: Purity, Joy, Reality, and Word-Flesh-and-Devil. Loy remixes allegorical characters typical of a medieval morality play in her en dehors garde drama in order to expose the old-fashioned ideas animating even the most modern performances. As the characters discuss “balancing accounts” in relation to “supply” and “demand,” we discover that they have orchestrated the entire spectacle. Their goal is neither to solve the problem of love nor end the sex war, but to “gloss over” the “mess” and “keep the surface glittering,” in order to insure a sold-out crowd for an age-old show. The epilogue exposes the producers’ complicity in the capitalist economy of mass commercial culture.

In Sacred Prostitute, Loy collapses the difference between virgin (Love) and whore (Procuress), showing how they both propel the same economy. Dolores acts as a commercial agent or go-between, further eroding the dichotomy between the sacred and profane. Loy does not exempt herself from the critiques of romance and commerce. Rather, she aligns herself simultaneously with the savvy but world-weary Dolores who arranges the match, the fatuous Love who falls for Futurism, and the cunning Procuress who produces the show. Wittily staging, restaging, and upstaging gendered roles, The Sacred Prostitute dramatizes how an en dehors garde artist may occupy multiple positions, assume different strategic poses, and be intimately and emotionally entangled in the sexual economies she critiques.

Loy’s Allegorical Method

As in Two Plays, Loy combines Futurist themes and techniques with popular forms such as puppetry and cinematograph. In Sacred Prostitute, she also incorporates inside jokes that reference Futurist manifestos, such as Futurism’s fantasy of all-male procreation, identification with the machine, and proposal to put glue on theater seats. Loy heightens the humor with elements of burlesque and variety theater (a venue that also influenced Futurist Theater). The play comprises a series of comical skits, held loosely together by common themes and stock characters, combined in absurd, surprising ways. But the biggest surprise in this experimental, en dehors garde comedy is its reliance on a traditional form of allegory that hearkens back to medieval and early Tudor morality plays and Renaissance masques.

Allegory is a narrative and dramatic form in which the story plays out simultaneously on two levels: the literal and the symbolic. Characters, plots, and settings “are contrived to make coherent sense on the ‘literal,’ or primary, level of signification, and at the same time to signify a second, correlated order of agents, concepts of events.” 5 Derived from the Greek “to speak otherwise,” allegory allows Loy to adopt and speak from an “other” perspective—to look beyond her personal predicament with the Futurists and see the bigger picture of the ongoing “sex war.”

Northrop Frye explains that “a writer is being allegorical whenever it is clear that he is saying, ‘by this I also (allos) mean that.”6 Writing allegory enables Loy to “also mean” something beyond the immediate situation being enacted. She stages scenes with characters who resemble herself and her Futurist cohorts, but who also represent symbolic concepts such as Don Juan, Futurism, Love, Nature, the Procuress of the World, and World-Flesh-and-Devil.

Through allegory, Sacred Prostitute retains grounding in Loy’s personal experience, while introducing a parallel dimension in which characters also represent abstract concepts and general types. For example, the minor character Tea Table Man is likely a version of Stephen Haweis, whom she described to Mabel Dodge as having a “parasitic orientation towards dillitante [sic] tea-tables.” But Tea Table Man’s allegorical name allows him simultaneously stand in for an individual in Loy’s personal life, and represent a broader type. In this way, characters become representative of gender scripts and social paradigms that govern private and public life and limit self-expression for even the most radical, groundbreaking artists.

Loy describes her method in an unusually long, self-revealing 1915 letter to Van Vechten, which begins with discussion of her ongoing revisions to The Sacred Prostitute and concludes with an ecstatic description of a new project7:

So I am writing a book now called ‘Possessions’ which is wonderful—I do really think it has something of genius in it—It is trying to ferret out the innards of the ‘Sex War’–as manifested in the passionately intense frictional attraction–between Genius & Woman. It is absolutely personal & entirely impersonal—It tries to analyze moods—newly—it never gets away from fact—& is tremendously imaginative—brutally impartial & never unkind—pathetically dramatic & very funny everything to quote myself ‘just is & there it is.’ But oh poor me it’s all about sex—& the artistic creative faculty—but the issues of course are something entirely transcending sex— I have tried to analyse—or give the impression on a ‘seeking neutrality’ of sexual intercourse—there is just one short bit—which I think is magnificent—But it’s something bigger than the thing as one is accustomed to accept it—

Loy’s explanation of her book sheds light on the allegorical method of The Sacred Prostitute, a play that also tries to “ferret out the innards of the ‘Sex War’” by staging “frictional” encounters between “Genius” (Futurism) and “Woman” (Love). Her allegorical approach makes the play “absolutely personal & entirely impersonal” at the same time, grounding the story in fact, while allowing for tremendous imaginative expansion. In this way, the plays are “all about sex—& the artistic creative faculty,” yet they also get at “something bigger,” addressing issues “entirely transcending sex.”

In her making Sacred Prostitute operate on two levels, Loy anticipates T. S. Eliot’s theory of poetic drama:

It is possible that what distinguishes poetic drama from prosaic drama is a kind of doubleness in the action, as if it took place on two planes at once. In this it is different from allegory, in which abstraction is something conceived, not something differently felt, and from symbolism… in which the tangible world is greatly diminished—both symbolism and allegory being operations of the conscious planning mind.8

The action in Loy’s play takes “place on two planes at once.” But unlike Eliot, however, Loy does not separate the intellectual, conscious mind from the physical and metaphysical dimensions of her poetic drama. Instead her eclectic, en dehors garde method combines poetry, allegory, physical comedy, and other forms to simultaneously entertain her audience and expand their imaginations.

Seeking an Audience

During her play writing period, Loy’s letters alternate between expressions of enthusiasm about her work and despair about her personal circumstances. Feeling isolated on the Costa San Giorgio, she was as desperate for an appreciative audience as she was for a compatible soulmate. “I am just hanging on to my sanity by a thread there’s not a soul here to talk to,” she confided to Mabel Dodge, “If I read my work to anyone they think I’m mad — Giovanni came within ace of really smashing me for good… too much sense of humour I suppose.”

Loy hoped Van Vechten would be more receptive to her work and would help her find an audience who appreciated her sense of humor. She was eager to publish The Sacred Prostitute and tried to arouse Van Vechten’s interest in the play, writing in a December 1914 letter, “I am going to send you — a part of the Love-Sex Review- ‘The Sacred Prostitute.’”

She sent him the play in separate “teaser” installments. When she got no response, she wrote again, pleading for his reactions: “Did you get the bundle of Conversational Sex-Love Review–I sent you or did they make so little impression–I am just going to send you the whole lot–& please give me your fullest attention–it’s so simple as to hide some of its subtlety.”

Loy recognized that the play would be a challenge for audiences, explaining to Van Vechten:

The first scene is irrational—intentionally—people may miss the significance of each point being negated by the next— But it’s most important— the psychological portent … is big — & new —”

Although she worried that the “Love-Sex Review” would confuse people, Loy was convinced that its insights were important and thought the public capable of grasping its “psychological portent.” She hoped Sacred Prostitute would amuse, cajole, and enlighten her audience, providing new insights into the age-old problems of love and sex.

The Sacred Prostitute suggests that commercial interests control the game of love and even the most free-thinking, avant-garde performers can’t break out of the plot. Nevertheless, Loy stages the entire enterprise in order to analyze it, get a purchase on it, and simultaneously amuse and enlighten her audience about the predicament we’re all in together. In this way, she doesn’t simply objectify her audiences as in Futurist theater, but gives them agency and respects their intelligence, trusting them to enjoy the entertainment and grasp its critique of larger social structures. Rather than attacking the audience for their naiveté, bourgeois values, and conventional tastes, Loy lets them in on the joke.

- Sara Crangle, ed. Stories and Essays of Mina Loy, Champaign, Dublin, London: Dalkey Archive Press, 2011, p.362-3.

- Janet Lyon, “Mina Loy’s Pregnant Pauses: The Spaces of Possibility in the Florence Writings,” Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, p.395.

- Charlie Chaplin, “A Night In The Show” (1915) | Public Domain Movies. https://publicdomainmovie.net/movie/charlie-chaplins-a-night-in-the-show-1915. Accessed 7 Apr. 2023. Scene starts at 9:12.

- ÉCLAIR BRUT, Arthur CRAVAN – Film Archives (Barcelone, 1916). YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5UEt4yziCd4&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 14 Mar. 2019.

- M.H. Abrams, “Allegory,” A Glossary of Literary Terms, 6th ed., Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College, 1993, p.4.

- Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays, Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 195,. p.90.

- Amy Feinstein quotes this letter at the beginning of her article, “Goy Interrupted: Mina Loy’s Unfinished Novel and Mongrel Jewish Fiction,” Modern Fiction Studies 51.2 (2005): 335-353. Examining Loy’s melding of “science and art, autobiography and experimentation, allegory and ethnography” in her in her unfinished 1930s novel Goy Israels, Feinstein does not identify the experimental method described in the letter as allegorical, although her article evinces Loy’s enduring interest in allegory.

- T. S. Eliot, “John Marston.” Essays on Elizabethan Drama. 1934; reprinted by Harcourt Brace, 1956. 173