In which our principal dancers, Loy and Stieglitz,

turn from Dada to more tangible pursuits

Alas, the American public did not get The Blind Man’s jokes. The irreverent little magazine “failed to provoke a scandal,” perhaps because no one read it, or because “a country at war could not tolerate such insouciance.”1

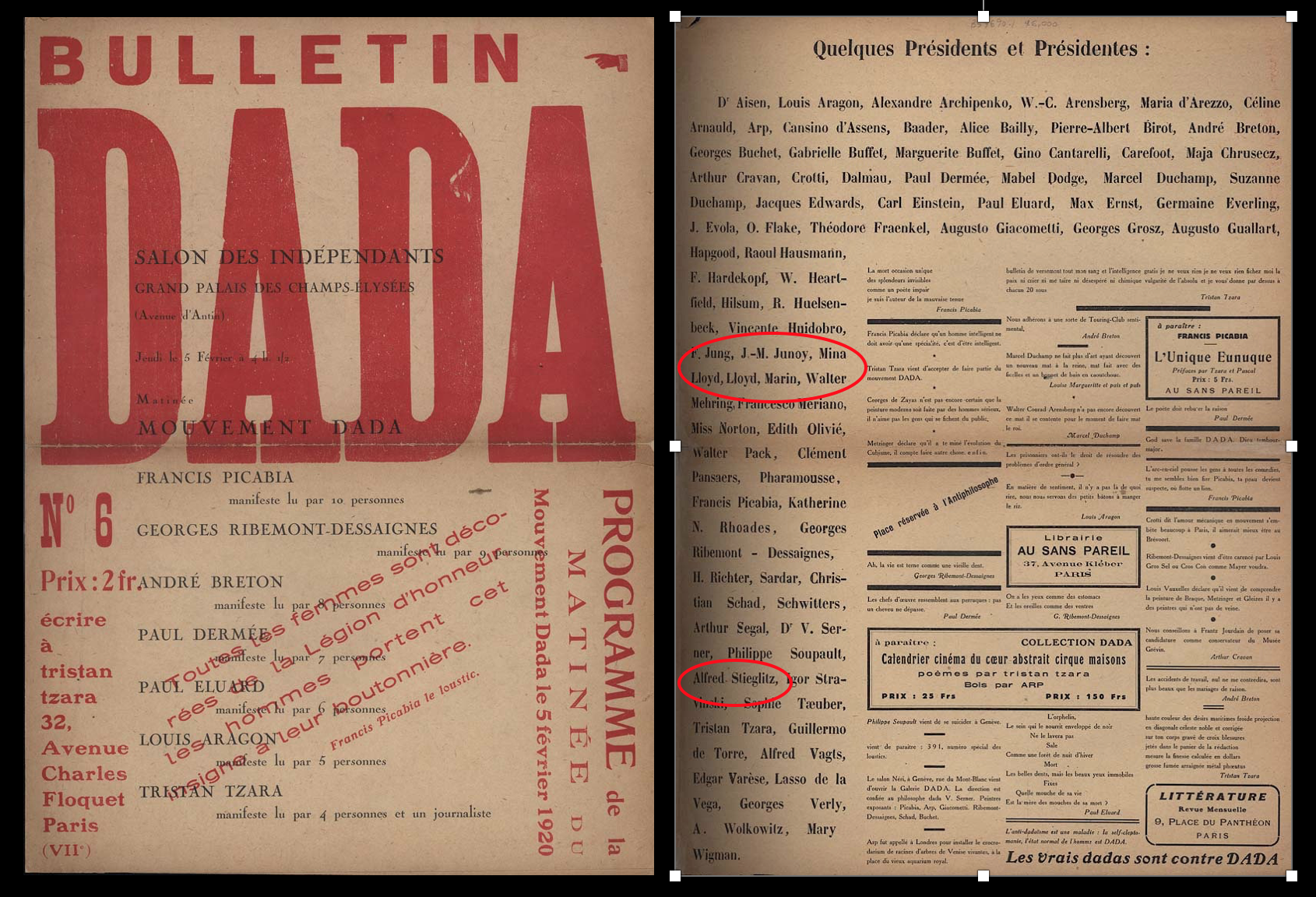

According to Francis Naumann, Francis Picabia and Tristan Tzara continued to champion Dada, “join[ing] forces to make Dada an international phenomenon” and working especially hard to promote it in New York newspapers.2 Although they “succeeded in generating precisely the publicity they sought” (Naumann 198), by the time they nominated Stieglitz and Loy to their roster of presidents in their 1920 Bulletin Dada, the two artists had already moved on to other pursuits. Stieglitz and Loy weren’t late for the Dada ball; rather, the ball was too late for them.

Stieglitz may have turned from Dada in part because it tried too hard to sell itself. First with the Modern Gallery and later in courting publicity for the international movement Dadaglobe, Picabia and Tzara embraced commercial tactics and advertised their program in a way that was inimical to Stieglitz’s anti-commercialism.3 Moreover, advertising, as Dada recognized, is an “ideatic” enterprise, selling not so much a product, but ideas such as sex, beauty, and power.

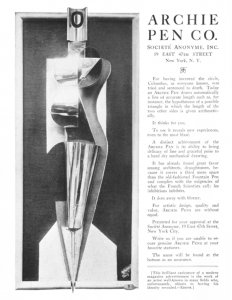

The crowning example of the marriage of Dada and advertising appeared in The Arts magazine in 1921, when the Société Anonyme Inc. published “an advertisement for the Archie Pen Co., an obvious pun on Archipenko, the Russian sculptor whose works were then being shown at the Société Anonyme” (Naumann 160-61). Of course, the pen did not exist—it was an abstract idea, another of Duchamp’s playfully elusive prods, as the editors explained, “This brilliant caricature of a modern machine is the work of an artist well-known in many fields who, unfortunately, objects to having his identity revealed” (qtd by Naumann 160-61).

Loy, meanwhile, turned from New York Dada prior to its dispersal in part because it did not sell. Her publications in New York little magazines made her no money, the Provincetown plays she starred in never made it to Broadway, and her scheme to sell tapestries failed (Burke 301). Her love affair with Cravan ended tragically when he disappeared somewhere off the coast of Mexico, and her embrace of the American public had not been reciprocated.

The American public was not as “jolly” as she’d hoped, as she explained to Mabel Dodge: “I have not been able to get along in the commercial field in New York because I cannot understand their distinctions between one nothingness and another” (qtd by Burke 304). Here, Loy portrays the world of commerce as an ideatic enterprise rather than an exchange of goods, a trade in “one nothingness and another.”

Perceived this way, the commercial field starts to resemble the Dada playground, which, Francis Picabia wrote,

smells of nothing, nothing, nothing.

It is like your hopes: nothing.

Like your paradise: nothing…” (qtd by Hartley 250)

A play of abstractions resulting in “nothing”—particularly no remuneration—could not satisfy Loy’s material and physical needs. “More absorbed in efforts to earn a living…than in her friends’ antics,” Loy turned away from New York and Dada. In 1919, she sailed to London, where she gave birth to Cravan’s child, Jemima Fabienne Cravan Lloyd. She then took the infant to Europe to meet Cravan’s family and see her other children, Giles and Joella, before moving to Paris intent on opening a restaurant (Burke 301, 303).

Meanwhile, according to Susan Rosenbaum, the New York Dada circle dispersed in 1921. Duchamp and Man Ray returned to Paris, reuniting with Picabia and Tzara in “a vibrant Dada scene” that soon disintegrated under the combined pressures of leadership struggles and anarchic energies. Loy remained on the margins of the Paris Dada scene, due to her feminist resistance to their gendered assumptions and behaviors, including their mythologizing of Cravan in a way that “implicitly cast Loy as the entrapping, pregnant wife” (Read more about Loy’s relationship to Paris Dada and emerging affiliation with Surrealism in Rosenbaum’s Surrealist Histories).

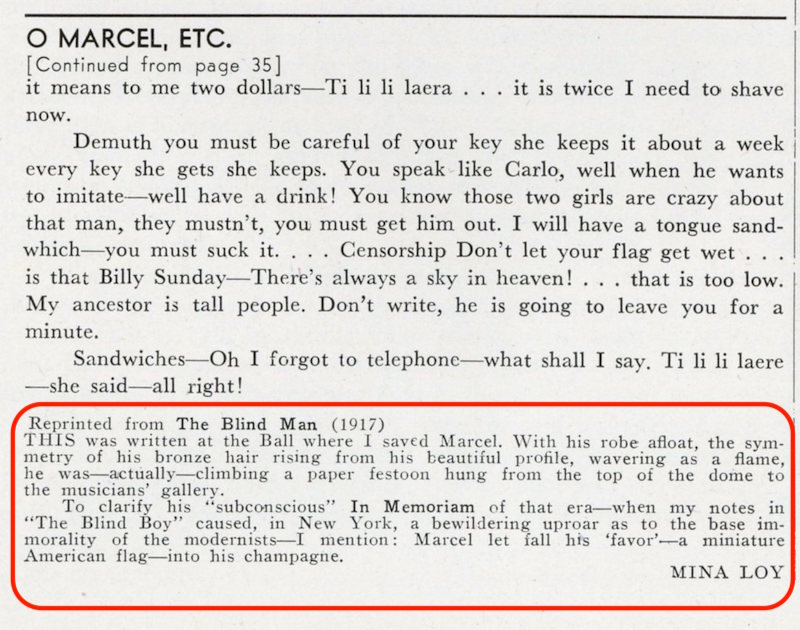

However bitter she was about Cravan’s disappearance and the resulting myths, Loy later expressed nostalgic affection for her dance with New York Dada. In 1945, when Loy granted permission to reprint “O Marcel” in an issue of View dedicated to Duchamp, Loy offer an explanatory note that resolves much of the sonograph’s ambiguity:

THIS was written at the Ball where I saved Marcel. With his robe afloat, the symmetry of his bronze hair rising from his beautiful profile, wavering as a flame, he was—actually—climbing a paper festoon hung from the top of the dome to the musician’s gallery.

To clarify his “subconscious” In Memoriam of that era—when my notes in ‘The Blind Boy’ caused, in New York, a bewildering uproar as to the base immorality of the modernists—I mention: Marcel let fall his “favor”—a miniature American flag—into his champagne.

MINA LOY (51)

Loy’s note confirms that “O Marcel” was an experiment in recording modern life as it happened at the Blind Man’s Ball in 1917. Describing Marcel’s “robe afloat,” “bronze hair…wavering as a flame,” and gymnastic movements, the note supplies the visual context so conspicuously absent from the scene as she originally recorded it, suggesting that, in memory, vision has overshadowed the sounds that once captivated her imagination. By clarifying the context, however, the note undoes its ambiguity, wresting interpretive authority away from readers and restoring it to the author’s name.4

The note also puts Loy in sympathy with Duchamp and the modernists and in opposition to an ignorant and prudish American public. Marcel’s nonchalant gesture of dropping “a miniature American flag” into the champagne suggests the superiority of French sophistication to American democratic ideals—ideals Loy seems to have turned her back on in disgust.5 But in 1917, during her brief dance with Stieglitz on the Dada stage, Loy made an en dehors garde turn outward to an American public she hoped would be receptive to her provocations.

- Carolyn Burke, Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1996, p.230, 246.

- Francis M. Naumann, New York Dada: 1915-23, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, p.198.

- See Stephen E. Lewis, “The Modern Gallery and American Commodity Culture,” Modernism/Modernity 4:3 (Sep. 1997), 85.

- See Erin McClenathan’s StoryMap of the Duchamp issue of View, in which the Loy piece was re-printed: this issue of the magazine sought to cement Duchamp’s name and reputation as central to Dada, and Loy seems to support this aim.

- As Taylor points out, the date of this flippant dunking of the American flag is significant, coming on the heels of the U. S. entry into World War I: “On April 6, 1917, exactly four days before the opening of the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition, the United States declared war on Germany” (210). American nationalism rose to a fever pitch, and as an English-born woman with French and Italian cultural ties, Loy may have felt especially alienated from the American public.