The Theater of Life

Perhaps in part because of her personal predicament, Loy recognized early on that the economies of sex, gender, and art were inextricable. According to Carolyn Burke, Loy moved to Paris in 1903 to advance her art career at the Académie Colarossi. There she met Stephen Haweis and soon became pregnant with his child, necessitating a hasty marriage “on the last day of 1903.”1 Oda Janet, a beautiful baby with violet eyes, was born five months later on May 25, 1904. Meanwhile, Loy had just begun to earn an audience for her work, exhibiting six watercolors at the prestigious Salon d’Automne in 1904, and getting two more accepted by the Salon des Beaux Arts the following spring. But then in May 1905, “Oda died of meningitis two days after her first birthday, and Mina nearly went mad with grief” (Burke 97-98).

The following year Loy was elected a member of the Salon d’Automne, yet once again, personal troubles disrupted her career. Estranged from her husband, she “drifted into a relationship with Henry Joel Le Savoureaux, the sympathetic doctor who treated her for neurasthenia after the death of Oda,” and became pregnant again(Burke 102). Haweis refused to divorce her, but agreed to claim paternity for the child on the condition that Loy move with him to Florence (Burke 104). With no viable options, Loy moved to Italy with Haweis in 1907. (Read more about Loy’s life in Florence in Linda Kinnahan’s “Mapping Florence: First Tour, Loy at Home.”)

Long a refuge for British families fleeing scandal and financial woes, Florence in the 1910s had become a hotbed for artistic, social, and sexual experimentation. There, Loy met Carl Van Vechten, the writer, photographer, and music critic who became her literary agent and epistolary confidante after he moved back to New York in 1914. Loy also befriended the free-loving salon hostess Mable Dodge, golden-haired Futurist artist Frances Stevens, uncorseted modern dancer Isadora Duncan and Duncan’s lover, English stage designer Gordon Craig. In the summer months, she rendezvoused with Leo and Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas to discuss the Paris art scene. And when Marinetti motored in from Milan to consort with Papini and the playboy-poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, she could indulge in heated verbal sparring and steamy flirtations. (Read more about the social scene in Florence in Kinnahan’s “Mapping Florence: Second Tour, Friends.”)

While gossip about personal dramas provided ample entertainment in the Florentine expatriate community, modern drama was also a popular topic of conversation. Haweis struck up a friendship with Gordon Craig, immersing himself in discussions about Craig’s “theater of the future” and creating plates of his innovative stage sets for publication in Craig’s theater magazine, The Mask (Burke 110-111).

According to Burke, Loy disliked Craig and “found his relations with Isadora Duncan far more interesting than his plans to modernize the theater” (111). But Loy had her own ideas about modernizing theater. Even if she disliked Craig, she would have had a hard time resisting The Mask, given how desperate she was for news of the art world beyond Florence and how often she pressed Van Vechten to send her magazines from New York. The Mask gave her ready access to “Magazine Reviews” of the latest issues of Camera Work, the English Review, the Century, and other journals; discussions of the latest developments in European theater; histories of folk drama and puppetry; and a translation of Marinetti’s 1914 manifesto, “Futurism and the Theatre.”

Summer Theater in Forte dei Marmi

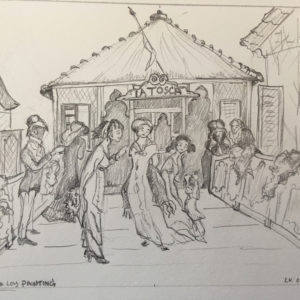

During the summers between 1909 and 1915, while staying at the seaside town of Forte dei Marmi with her children, Loy may have attended open air theater productions. One of her paintings from this period depicts what appears to be an entrance to a performance of La Tosca, although on the back of the painting, Loy has written “Maison des bains a Forti dei Marmi” (bath houses at Forte dei Marmi), suggesting the scene could be an entrance to a private beach.

According to Linda Kinnahan,

‘La Tosca’ was originally a play by Vitorien Sardou, premiering in Pairs in 1887 and continuing to be popular into the early 20th century. It played at London’s Lyceum Theater in 1888 and toured the world thereafter. Sarah Bernhardt played the title role, making the play quite popular. Set in Rome, the play involved the characters of Floria Tosca, a celebrated opera singer, and her artist lover Cavaradossi, arrested by Rome’s evil Regent of Police, Baron Scarpia, and imprisoned in the Castel S’Angelo. The officer demands sex from La Tosca in exchange for her lover’s release, and she pretends to agree but takes the opportunity to stab him to death. In the meantime, the order has already been given for Cavaradossi’s execution. When La Tosca learns of his death, she throws herself to her death from the heights of the Castel S’Angelo.

In 1900, the Giacomo Puccini adapted the play as an opera, “Tosca,” which opened that year in Rome. Puccini (born in Lucca) lived at the time in Torre Del Lago, a village very close to Forte dei Marmi, where Loy spent several summers while in Italy. Puccini lived in Torre del Lago from 1900 until 1921, overlapping with Loy’s years in Florence and visiting Forte dei Marmi. He knew and associated with Gabriele D’Annuzio, who lived in the Villa la Versiliama in the early years of the 20th century (in the Versiliana Park, on the edge of Forte dei Marmi). Loy, of course, references D’Annunizio in poems like “Lions Jaws.”

Whether it depicts a bath or theater entrance, however, the scene has a stagy, theatrical feel, as you can see from Linda Kinnahan’s sketch of the painting:

In this scene, the people lining up to enter “La Tosca” are themselves performers. Dressed in elegant costumes, they pose on the boardwalk, observed by curious onlookers on the sidelines. “Maison des Bains” depicts the theater of life, displaying Loy’s keen interest in gender performativity.

Use the arrows to take a guided tour of Maison des Bains a Forte dei Marmi

To read more about this watercolor & Loy’s stays in Forte dei Marmi,

navigate to Kinnahan’s “Italian Retreats.”

The Florentine Players

Back in Florence, Loy learned about experimental theater in America from Neith Boyce and Hutchins Hapgood, resident representatives of the Provincetown Players. From them, she may have learned about playwrights such as Susan Glaspbell and Rachel Crothers, who took up questions of women’s rights and roles, using realist approaches to interrogate gender inequality in art and life. Glaspell’s one-act play Trifles was performed by the Provincetown players in 1916. Crother’s 1911 play He and She, a battle of the sexes between husband and wife artists, became a Broadway hit in 1920. If Loy’s satire of the sex war, The Sacred Prostitute, wasn’t directly influenced by these early feminist dramas, it partakes of the same zeitgeist. The Provincetown Playhouse’s openness to feminist experiment may have appealed to Loy when she agreed to star with William Carlos Williams in Lima Beans in 1917. She may also have appreciated the Provincetown Players’ collaborative approach to audiences. In contrast to the Italian Futurist’s combative relationship, “American poets sought to restore the audience within a social theater, equally engaged in the rituals and realizations of the modernist stage.”2

While in Florence, Loy could only experiment in the theater of her imagination. She engaged in probing discussions about dramatic theory with Herbert Trench, a British poet, playwright, and former director of the Haymarket Theatre, reporting to Van Vechten:

Trench is writing a tremendous play—& the theory at the back of it which is all he has imparted to me so far—is so deep—I wonder where the public is to come from—The Futurist Theatre is very poor by the way—there is little being evolved here. I wrote a play called ‘The Pamperers’—which is simultaneously a parody of the “Genius”—& the society that takes him up—it’s a good deal longer than the ones in Rogue—the hero is a man who picks up cigar ends.

In rapid fire, Loy expresses her interest in dramatic theory, her concerns about a “public” for theater, her dissatisfaction with Futurist Theater, and her excitement about her own advances in play writing.

Female Roles & Feminist Ploys

Within the limited orbit of the expatriate community of Florence, Loy was able to observe the conversations, interactions, and theatrical antics of the avant-garde from close-range. She analyzed everything she read and saw, trying to understand how the modern art world worked and what was not working—why the Futurists were not living up to their own revolutionary rhetoric, and why her own position as an “exceptional woman” was not leading to artistic or sexual fulfillment, but rather to disappointing love affairs and suffocating isolation.

Although Futurism may have woken her up, it did not turn out to be a high-speed train ticket to emancipation. Loy simply couldn’t exercise the same artistic freedoms Marinetti and Papini enjoyed, particularly in pre-war Italy. Without a license or a car, she couldn’t drive through the city streets, hurling posters and expletives at passers-by. She couldn’t stir up interest in the local cafes without endangering her reputation, as “Ladies did not venture into such places” (Burke 106)—at least not unchaperoned. Loy and Haweis did attend Futurist gatherings at cafés such as Giubbe Rosse and were referenced in Lacerba as part of the Futurist café crowd (Kinnahan, Hypothesis annotation, 30 May 2019).

While Loy was able to venture out accompanied by her husband, women in pre-war Italy were largely confined to domestic spaces and feminine activities, as Loy sardonically observes in her poems of the period: “all permissible pastimes” were “Attendant upon chastity,” and young women spent their lives “chasing moments from one room to another” (“Italian Pictures,” LLB96 9). Unmarried women were effectively prisoners of the bourgeois home: “Houses hold virgins / The door’s on the chain” (“Virgins Plus Curtains Minus Dots,” LLB96 21). Women could not appear in public, much less assume the stage to publicly challenge sexual propriety, without seriously risking their reputations.

Loy’s reputation was especially vulnerable. Although she was estranged from her husband, “divorce was out of the question, since any impropriety meant the end of her income” (Burke 102). Stepping out of bounds in person or in print could lead to getting cut off by Haweis or disowned by her family. “Do you notice how frightened I get like a small child when I have written anything I mean,” she confessed to Van Vechten, “I feel my family on top of me” (quoted by Burke 192).

Nevertheless, she persisted. Writing gave her a vehicle for analyzing her predicament. In addition to poems and manifestos, she wrote fragmented roman-à-clefs that restage scenes from her exhilarating and frustrating encounters with Marinetti and Papini. A sense of drama and theatrical tropes permeate her poems, roman-à-clefs, and art from this period, even as they provide impetus for her plays. Loy’s poems and roman-à-clefs provided a way of thinking about sex war on an intimate scale, while giving her critical distance from her own dilemmas. But the more public-oriented plays offered her a larger stage in which she could move from analyzing her personal plight to investigating social roles, psychological patterns, and gender structures. In a sense, Loy was looking for love, seeking satisfying relationships in both life and art, because for her, life and art were inextricable.

Loy was not merely interested in solving her own personal problems through her writing; she wanted to examine the big picture and understand her position in a much larger system. Playwriting allowed her to explore her personal predicament on a public stage, transforming and generalizing her experiences into art. Her plays offer an insider’s view into the structures and operations of the historical avant-garde, providing en dehors garde insights into her evolving understanding of the artist’s relation to audience and the performative nature of gender.