by Carolyn Burke

Voyages in Time

This talk takes us on a series of voyages looping backwards and forwards, all in the past. At the same time it is an emblem or allegory of how the life of a modernist—a modernist life?—may get written, given the accidental, even unlikely nature of the materials that survive, and their fragile, fragmentary, damaged condition. It will illustrate, I hope, the way this biographer worked to restore such materials, to recompose them into a plausible whole.

Prelude

In the 1970s, when I first came across the name Mina Loy, I was living on the rue Campagne Première, where she too had lived, and reading expatriate memoirs, including Peggy Guggenheim’s Out of This Century. In 1976, after I began my research on Mina, I wrote to Peggy to say that I was coming to Venice and hoped to speak with her about their relations during the 1920s, when she had backed Mina’s lampshade business. We are making our way, as I did, down the Grand Canal toward San Giorgio for our first view of Guggenheim’s home, the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni.

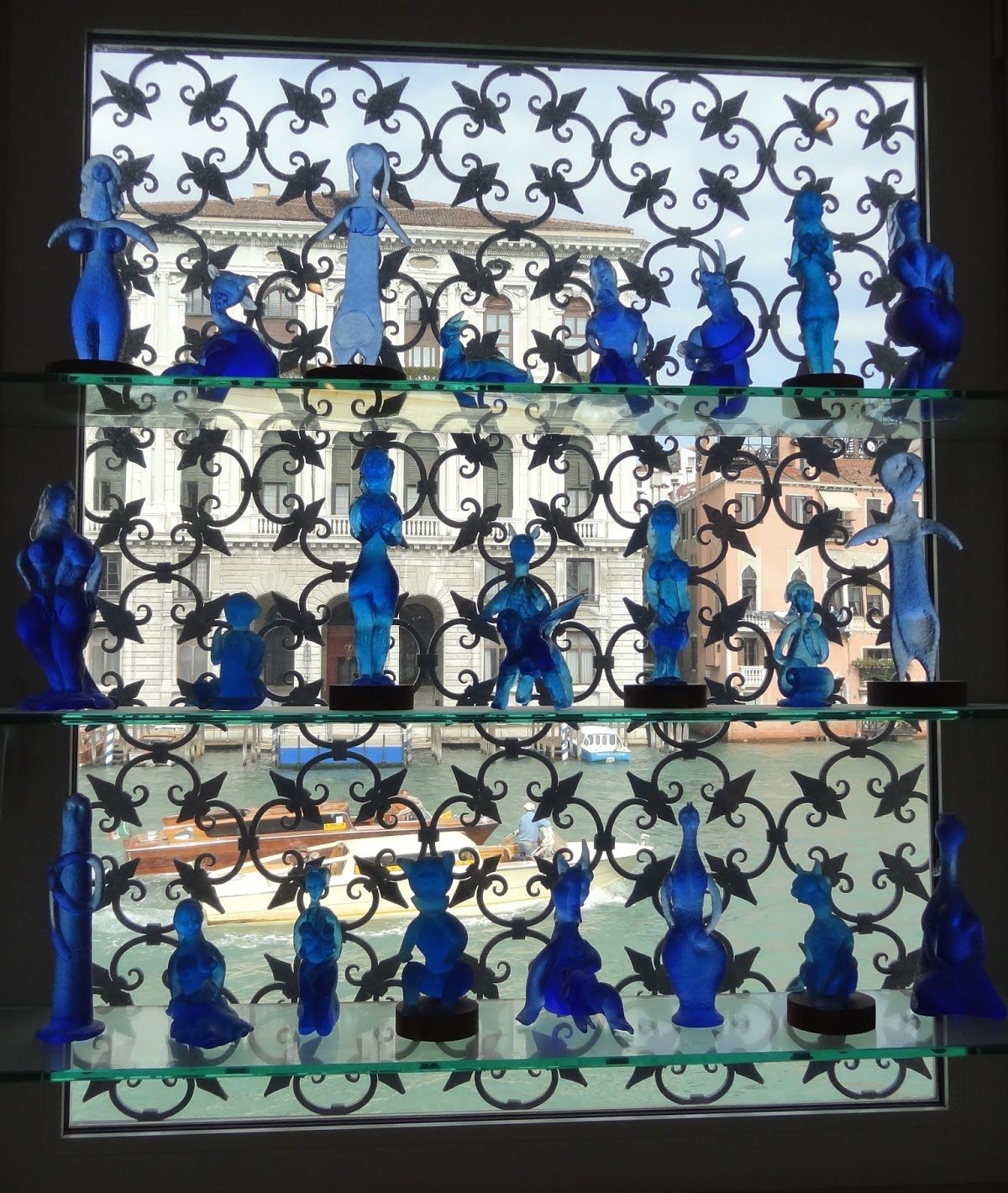

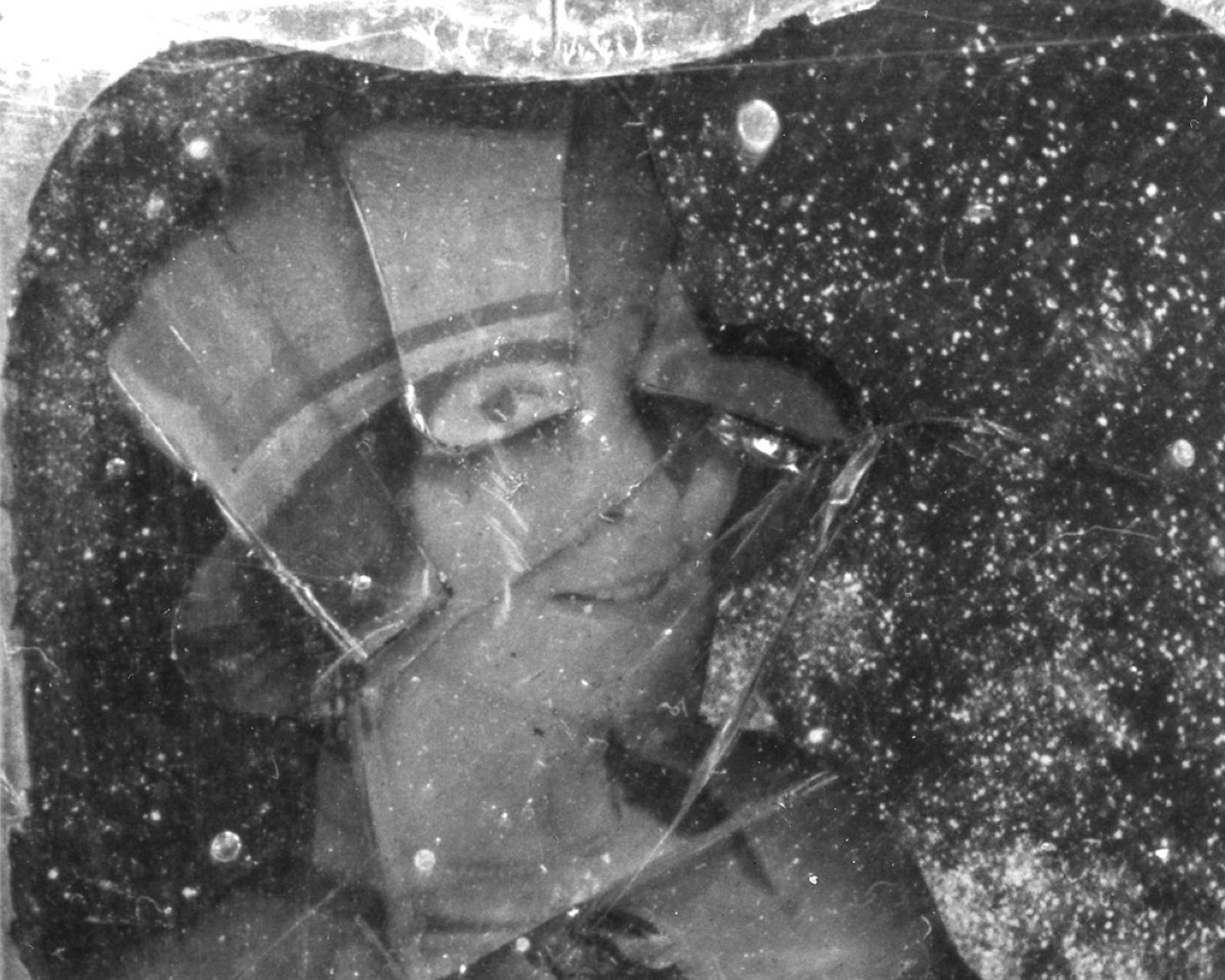

To my mind’s eye, this interior view from Palazzo Guggenheim to the Grand Canal (below) evokes a quintessentially Loyian image, Mina’s childhood memory of the shards of glowing color that she yearned to possess—the glass fanlight above the door of her London home. The blue of Venice, which also recalls that of Loy’s 1933 solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s art gallery in New York, offers us a series of looks into the past, to introduce both Mina’s and my own.

Reconnaissance, 1977

I prepared for my trip to Venice at the Bibliothèque Forney, Paris, in an effort to find out more about the missing lampshades. In tattered issues of Art et Decoration from 1927 and 1928 I found black and white pictures of several of them, including “L’Ombre Féerique,” “The Corvette,” and “La Galère.” I had them photographed but could not find any originals. It seems that none survived due to the fragility of their materials—most of which Loy found at the marchés aux puces (Paris flea markets).

I had written to Peggy Guggenheim from Paris with questions about the lampshades. When I arrived at the Palazzo, she received me courteously, but said that she could remember nothing about those days except that they had been friends. She did, however, own a Mina Loy. Would I like to see it? I said yes, I would, astonished at this serendipitous opportunity.

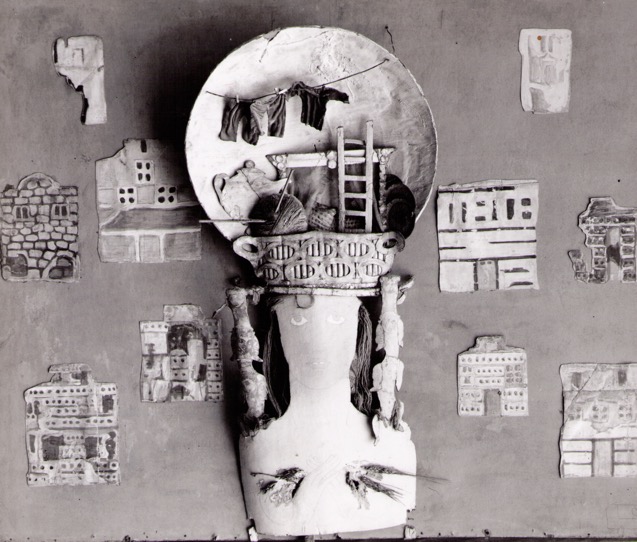

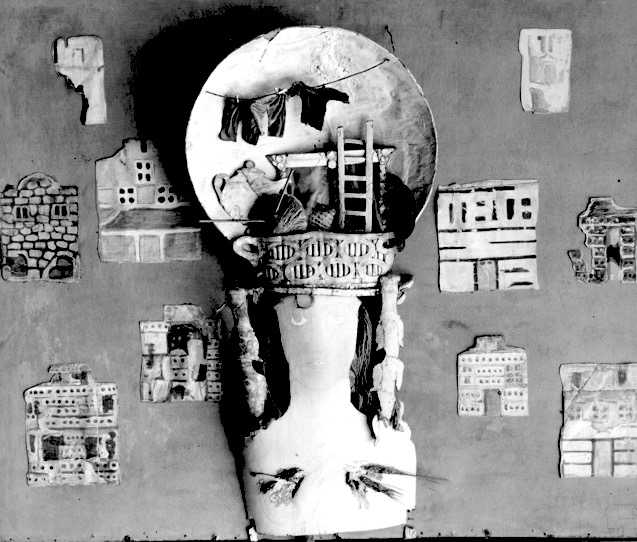

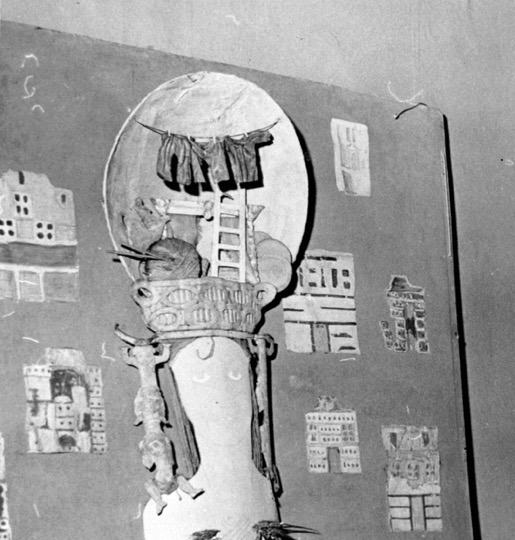

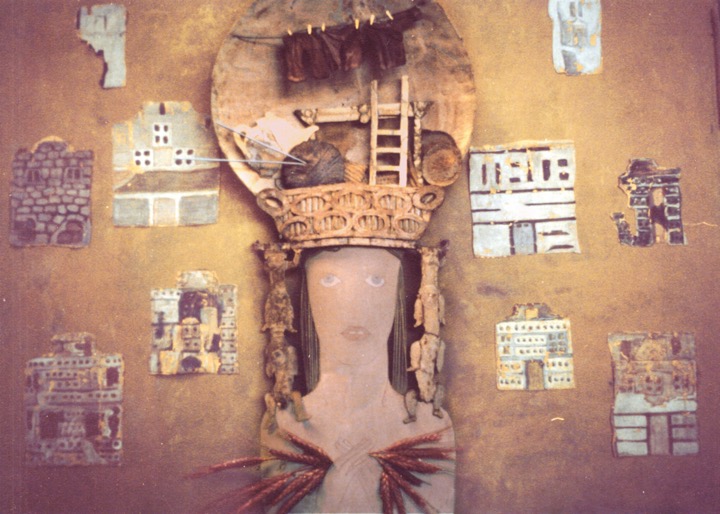

Peggy took me to the palazzo’s private wing and into her pink bedroom, where I saw Househunting for the first time. She left me alone there; I meditated for a long time on the almost pre-Raphaelite central image before returning to my scholarly preoccupations.

I noted the hand-made details—the basket on the woman’s head backed by its opaque aureole—her crown?—with its imagery, a ball of wool and needles suggesting a play on the notion of ouvrages de dame (women’s work); a teapot and plates; the sheaves of wheat the woman held to her chest; the ladder leading up to a clothes line; and most strange, to my way of thinking, two putti (naked children) dangling like earrings on each side of her head. In the background, cardboard cut-outs resembling fragments of houses, all somewhat Italianate, suggested the woman’s many abodes. The colors of the work, her pink visage and the rosy-beige background, glowed against the bedroom’s pink walls. Was this assemblage a kind of dream, a way to recompose the times and places of its subject’s past?

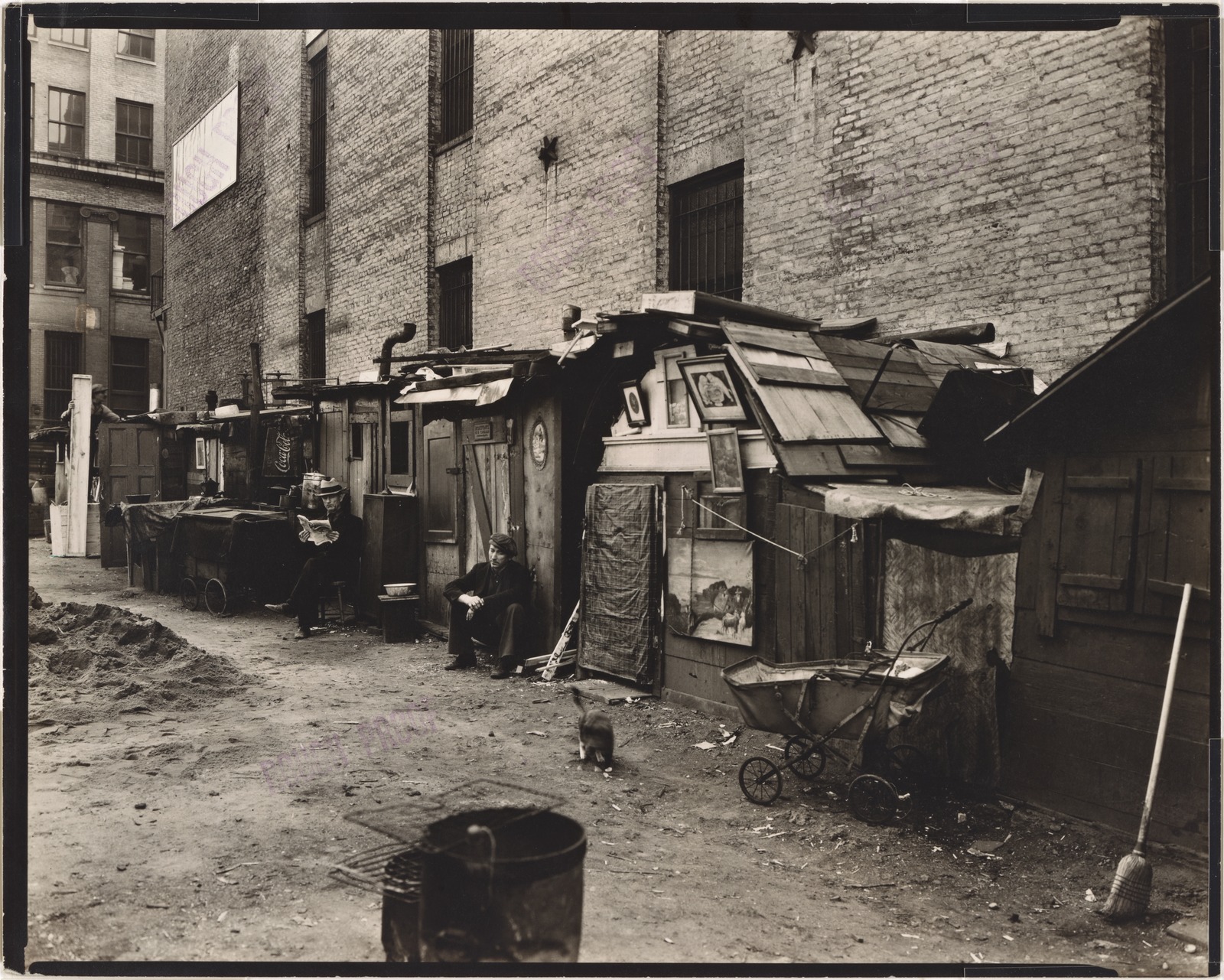

At the same time I was struck by the contrast between Loy’s vision and Guggenheim’s palazzo. I knew that Loy had constructed Househunting in the early 1950s, when she was living in a communal household near the Bowery, on Stanton Street, and writing poems about the unhoused, or as we would say today, the homeless. She had settled in this disreputable part of New York in 1949, a time in her life that provides the backdrop to the rest of my story.

Backdrop, New York, 1940s

By 1937, when Hitler was speaking openly about the Germans’ need for greater Lebensraum (“living space”), Mina left Paris to live in New York with Joella and Julien Levy, her daughter and son-in-law. By 1940 she was sharing a rooming-house apartment with Fabienne, her younger daughter. As they moved further downtown, where rents were cheaper, Mina gradually willed herself “to share the heedless incognito” of the urban crowd (“On Third Avenue”). In those years, Joella believed that Mina “was at her maddest”—depressed, isolated, obsessed with her inventions, some of which she hoped to patent and sell to prominent companies, such as Helena Rubenstein. In 1949 she settled on her own in the Stanton Street communal household where, with the help of three figures from her past—Joseph Cornell, Dorothy Day, and Berenice Abbott—she began the series of objects (her term; they were later renamed “constructions” by Julien Levy), drawing inspiration from her surroundings, including Househunting, which in some ways typifies this late phase of her artistic production.

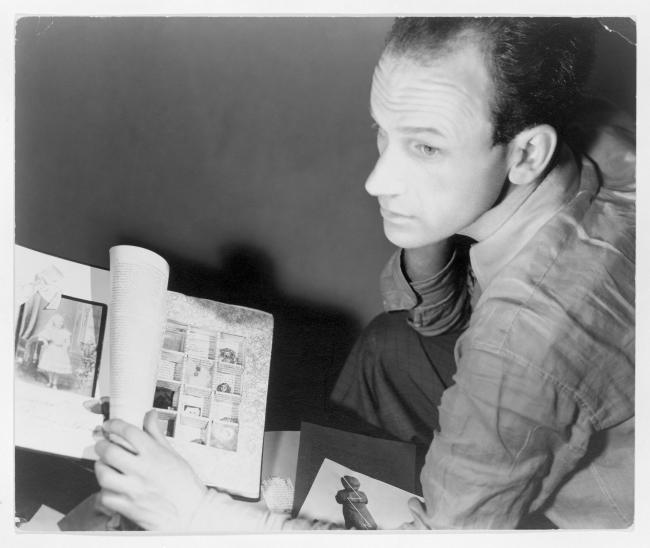

Julien Levy had introduced Joseph Cornell to Mina a decade earlier, when he gave to Cornell the antique boxes from the same Paris flea markets she frequented. By the 1940s she was a fixture of Cornell’s image inventory—as an older beauty, a kindred spirit, and an artist of a particular sensibility. He treasured the portraits of herself that Loy gave him for his “image-research.” What was more, they both practiced Christian Science. Its “white magic,” Cornell believed, offered an antidote to the Surrealists’ darker spirit. Mina introduced him to the spiritual vision of Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes (The Wanderer), the book that inspired his boxes on the theme of the enchanted castle—to his mind, one of the many fortunate outcomes of their close personal and artistic friendship.

It is likely that the example of Cornell’s shallow boxes filled with unusual findings in turn nourished Mina’s thoughts about her Bowery constructions on the themes of home, and homelessness.

By the time that Cornell made Portrait of Mina Loy she had long been part of his constellation of images. The portrait, which contains a Man Ray photograph of Loy from the 1910s, is inscribed on the back with the phrase “imperious jewelry of the universe,” the line from her “Apology of Genius” that had been included in her 1933 Levy Gallery catalog.

In an homage to the dominant blue of Loy’s exhibition, Cornell placed shards of blue glass among the materials that comprise this delicate tribute to her as an artist and a poet. She in turn considered Cornell “one of the angels.”

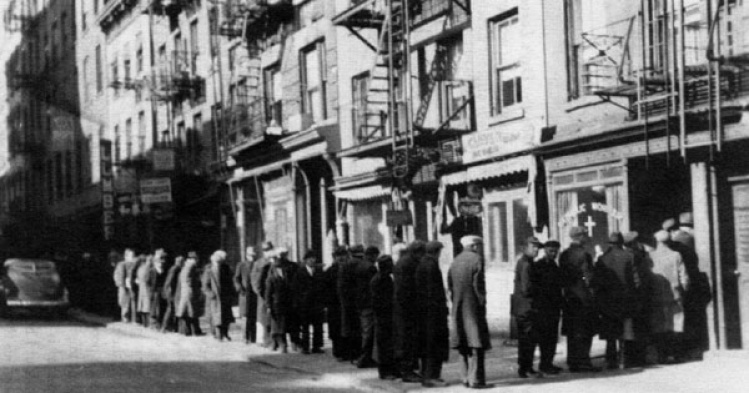

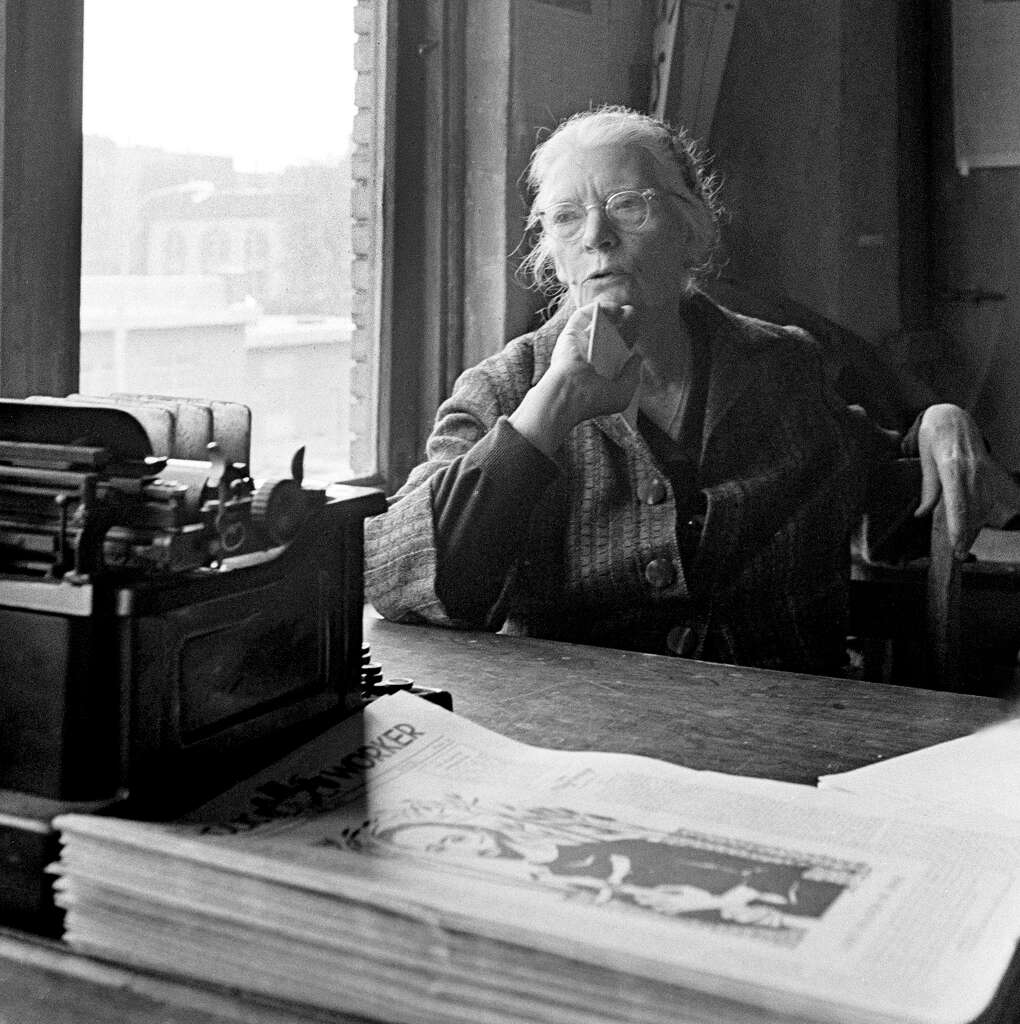

If Cornell was an angel, to many Dorothy Day was a kind of secular saint. Her engagement with the Catholic Worker movement became an important source of inspiration for Mina once their community moved to Chrystie Street, around the corner from her communal household on Stanton.

Mina took an interest in aspects of the group’s dedication to their work, including their soup kitchen, housing program, and progressive newsletter The Catholic Worker, to which she subscribed. To those in the know, Day’s editorials in the Worker read like neighborhood gossip columns with a spiritual stance. Even after moving to Aspen in 1953, Mina continued to correspond with friends at Stanton Street about the goings-on at the Catholic Worker.

Mina and Dorothy had been acquainted since the 1910s, when Mina acted at the Provincetown Playhouse and Dorothy worked for the left-wing periodical The Masses. Day’s conversion from her early political activism to the practice of bearing witness in community service encouraged Loy to envision her own “compensations of poverty”—the shallow three-dimensional objects that bore witness to life on the Bowery.

Loy had also known Berenice Abbot, the third figure to provide support at this time, at the Provincetown Players in the 1910s, and again in expatriate Paris, as Man Ray’s assistant and part of the lively Montparnasse set. Of their Greenwich Village days, Abbott said decades later, “we were all pacifists then.” Having looked to Loy as a great beauty, she remarked, “when a lovely woman grows older it’s a tragedy for her.” Mina turned inward, Abbot believed, in her reflections on the lives of her new-found subjects, the bums.

Of her visits to Mina’s neighborhood, Abbott continued, “It was like wandering around in hell, everything in brownish tones, everyone was alone.” Abbott tried to help Mina by photographing her constructions gratis, an exception to her usual practice, and by steering her to galleries that might take an interest in her work—to no avail.

Mina’s poem “Hot Cross Bum,” a guided tour of the Bowery, describes it as an urban hell but also a “sanctuary,” where the residents, its “blowsy angels,” work out their own approaches to salvation. The poem includes a parodic communion offered by “some passing church/or social worker” (the Catholic Worker group?) at which the officiants’ “egoless eagerness” encounters the “impious” mysticism of the bums.

Stanton Street Constructions, c. 1950 to 1952

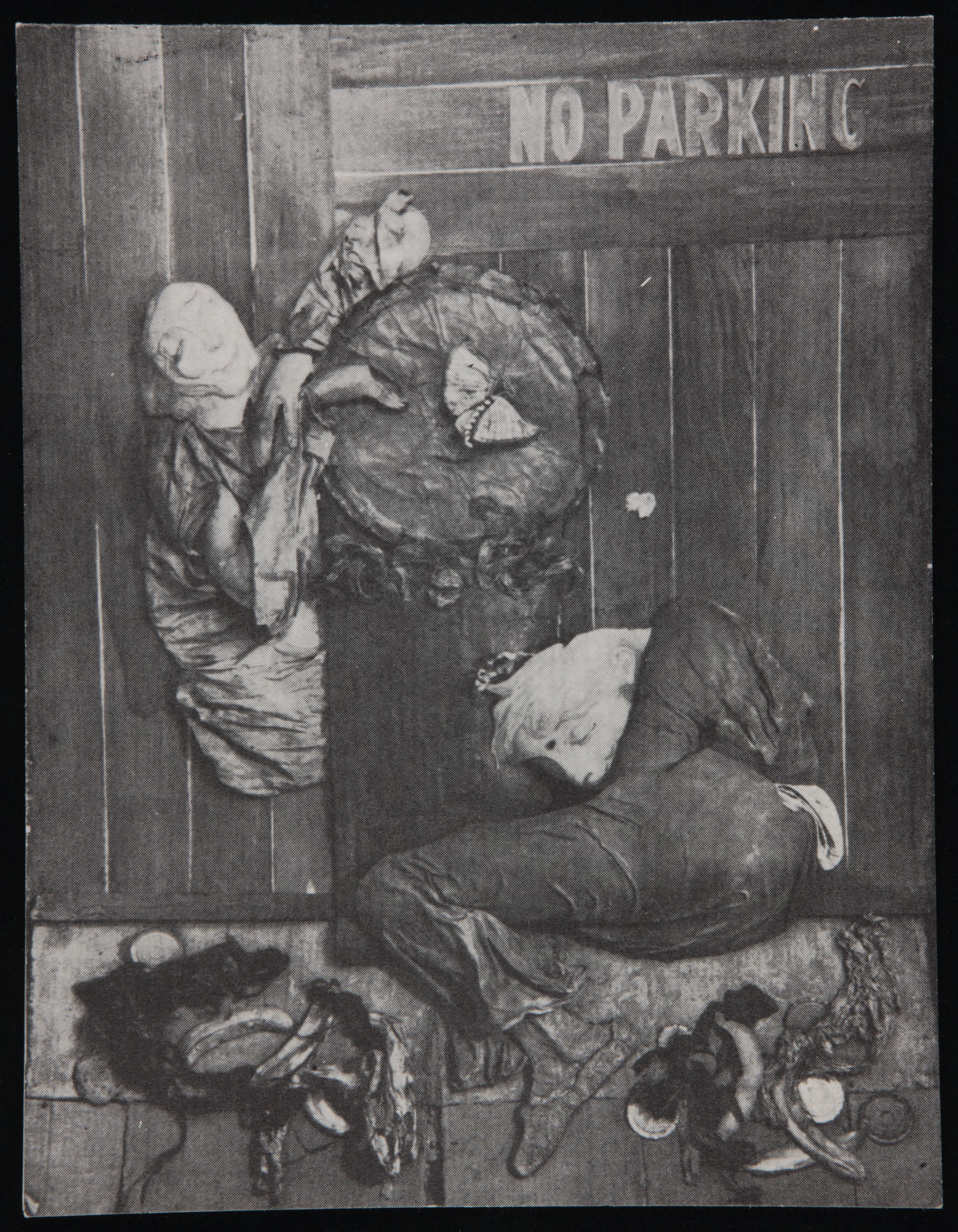

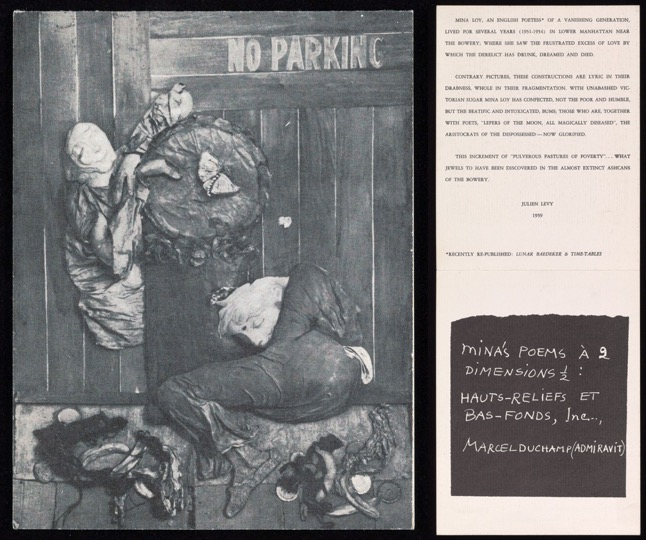

In a photograph of No Parking taken by Berenice Abbott, one can see bits of the room where Loy stored her constructions after settling in Aspen (the original construction is lost, and licensing fee’s for Abbott’s photo were cost prohibitive). The rare visitors at the time often felt assaulted by the contrast between the delicate modeling of the derelicts’ features and these works’ sordid materials, made of actual refuse, used to depict their surroundings. Still, some understood the scene’s central image, the trash can out of which a butterfly arises: “That image, the plea of discarded life to be reanimated, inspires all of these works, in which the common becomes triumphant through a spiritual effort” (clipping from Arts, 1959).

Like No Parking and other constructions, Communal Cot was fashioned from the overflowing detritus of the streets. Mina brought to her shabby materials an acute sense of the cost involved for those who searched the garbage cans, those who lived at the bottom of the heap. At the same time, she saw such figures as saintly, as in this depiction of sleeping derelicts as a contemporary version of the twelve apostles.

Similarly in Bums Praying (aka Bums in Paradise) the five enrobed figures seem to transcend their bodily circumstances in prayer, however ironic. In them, the Stanton Street household recognized Mina’s models, the derelicts she sometimes hired to pose for her and paid in small change, with which they bought supplies of cheap red wine, known locally as “creepy Pete.”

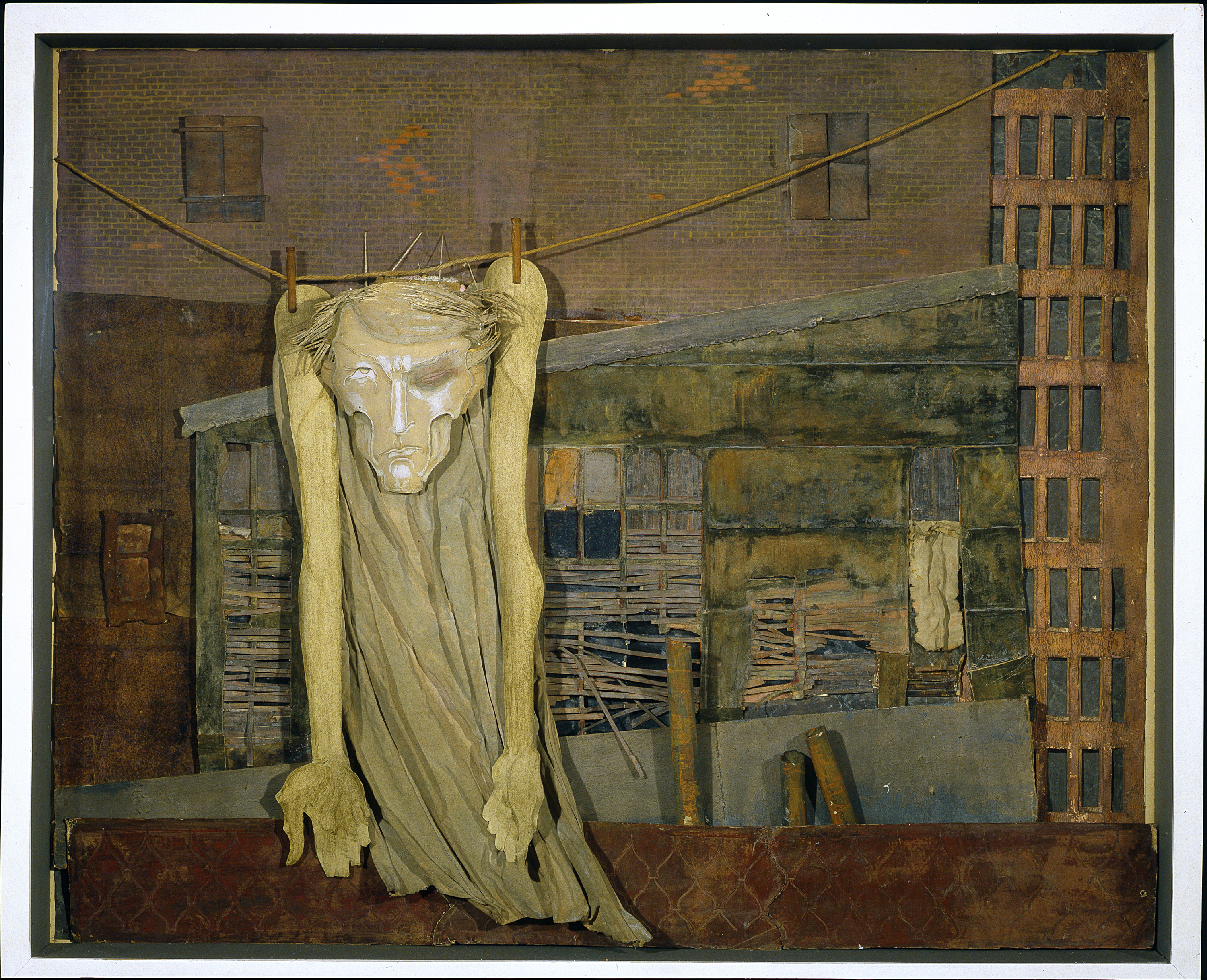

In Christ on a Clothesline, they all recognized the tubercular Scandinavian fisherman whom Mina chose as the model for Jesus, because of his trade and his emaciation. Surely the most disturbing of the series, this construction puts the viewer on the roof of a Bowery tenement, in the place of an awkward passer-by. One senses that his spirit is on the verge of departing: his cadaverous face stares straight at us in outraged accusation.

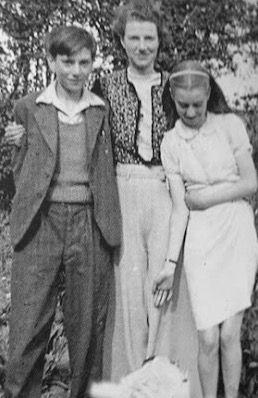

Househunting at Mina’s apartment, before it was bought by Peggy Guggenheim.

Visit to Stanton Street, 1959

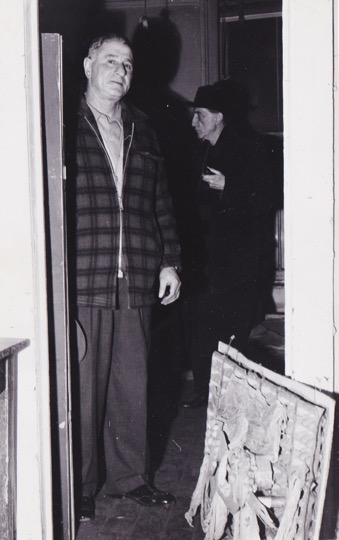

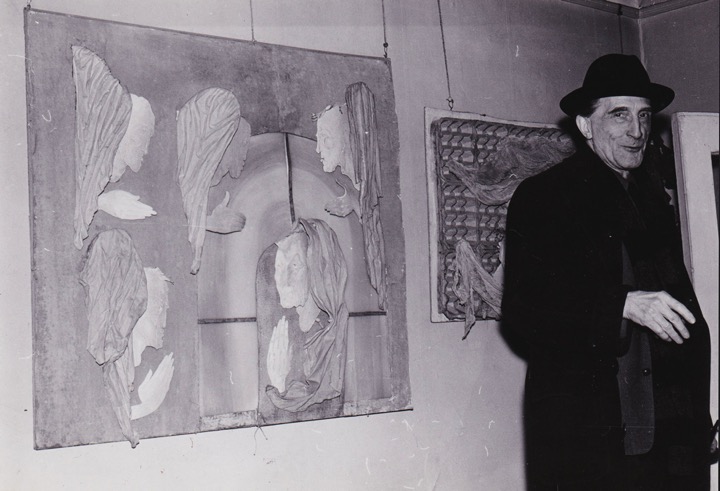

Five years after Mina moved to Aspen to be with her daughters, her constructions, including Househunting, were still in her Stanton Street apartment. They stayed hidden under their dust cloths until 1958, when Marcel Duchamp brought David Mann, the director of the Bodley Gallery in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, to see them. Mann gave me these photos, which document their visit to Mina’s neighborhood and their discovery of the work that formed her response to the winos who looked after her and called her, affectionately, “our Duchess.”

We begin at Al’s Bar, the local hangout owned by Al Bossom, Mina’s landlord and, in a sense, her protector as well as the protector of the bums (he doled out their finances, a nickel at a time). Mina knew each by name; they revered her; some welcomed opportunities to pose or do her errands for a quarter. She in turn admired their stoicism and their otherworldliness, an attitude toward “deprivation” that she hoped to convey in her constructions.

When writing “Hot Cross Bum,” Mina verified intimate details of her derelict friends’ lives, such as their fondness for rotgut. She read successive drafts of the poem to members of her household, one of whom described her “in full sail floating down the Bowery in her maroon housecoat and white hair, holding her pencils and pens, greeting the bums… They loved her” (Stephen Ferris, letter to Carolyn Burke).

David Mann joined Bossom, Duchamp, and Georgie Duffee, co-owner of the Bodley Gallery, at Mina’s apartment to inspect her objects.

According to Mann, Duchamp too adored Mina and called her “a genius.” Urging that her work be shown at the Bodley, he commented on each construction but in self-effacing fashion wanted no credit for the show.

Moved by the Surrealist mix of grim subject matter and tenderness of mood in these pieces, as well as their original use of what others called arte povera (poor art), Mann was struck by Loy’s gentle approach to the theme of homelessness, as well as her use of such materials as Quaker Oats boxes, egg cartons, clothespins, and other sorts of refuse.

As they stared at Househunting, Duchamp insisted, “you must do the show.” Bossom, Duchamp, and Mann packed up the objects, put them in the gallery’s station wagon, and took them uptown to the gallery, a deeply ironic shelter for Mina’s “Refusees”—another of her proposed titles that neatly summed up her life in its punning blend of refuse, Refusés (cf. the Salon des Refusés), and refugees.

Bodley Gallery Show, New York, 1959

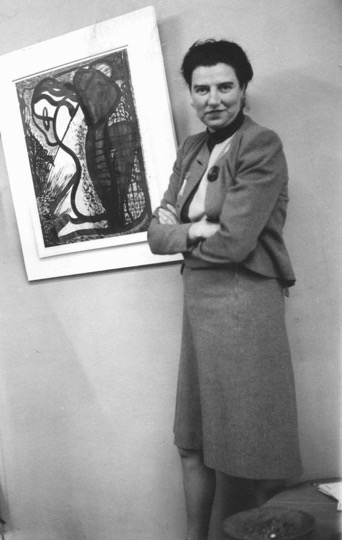

During the 1950s the Bodley Gallery, a showcase for Surrealist and contemporary art, exhibited such artists as Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Andy Warhol. Although Loy’s belated recognition came too late for her to enjoy in person, her exhibition was celebrated by her friends and admirers at the vernissage (private viewing): among them, Max Ernst, Duchamp, Cornell, Djuna Barnes, Frances Steloff of the Gotham Book Mart, and Peggy Guggenheim, who was “amazed to see everyone.” Mina’s old friends phoned to congratulate her in Aspen; she often called Mann to tell her about her latest work.

Julien Levy wrote a poetic description of her objects for the invitation: “Contrary pictures, these constructions are lyric in their drabness, whole in their fragmentation, with unabashed Victorian sugar.” Her subjects, he continued, were “the beatific and intoxicated…those who are, together with poets, ‘lepers of the moon, all magically diseased,’ the aristocrats of the dispossessed.” Duchamp wrote more succinctly, “MINA’S POEMS À 2 1/2 DIMENSIONS; HAUTS-RELIEFS & BAS-FONDS, INC.. MARCEL DUCHAMP (ADMIRAVIT).”

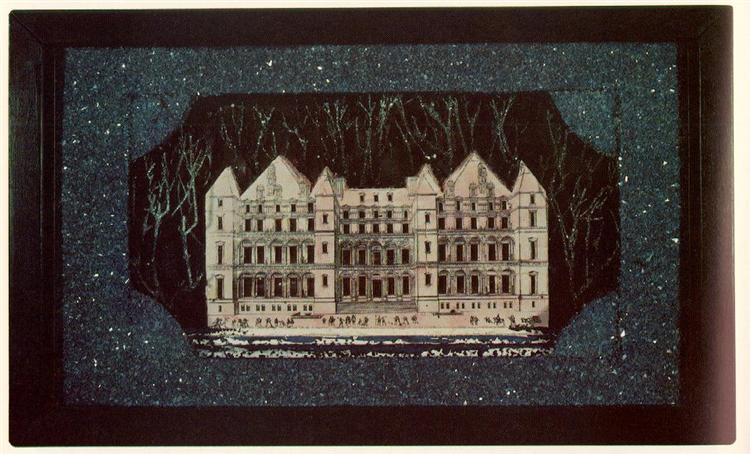

Peggy Guggenheim, whose Art of this Century gallery had featured work by some of their mutual friends among the modernists in the previous decade, bought Mina’s Househunting that night. One wonders what attracted her to this idiosyncratic work: perhaps its formal elements, the architectural details combined with the modernist use of fragments, the mixtures of tones and messages, above all the evocation of the aesthetics of the “Old Crowd” at a time when New York critics favored the non-representational aesthetics of abstract expressionism.

While Art News dismissed Mina’s constructions as “theatrical trappings dripping with sentimentality,” The New Yorker’s critic Robert Coates, who knew her in Paris, wrote of them: “the fact that they are focused on the life of the derelicts on the lower East Side establishes them as studies of the Lower Depths. For all their grim subject matter, however, the mood of the show is tender, and in its own uninsistent way, extremely moving.” Several pieces sold, Househunting to Guggenheim and No Parking to Frances Steloff, who displayed it in Book Mart’s window along with Mina’s 1958 book of poems, Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables.

Retrieval, Paris & Venice, 1985-86

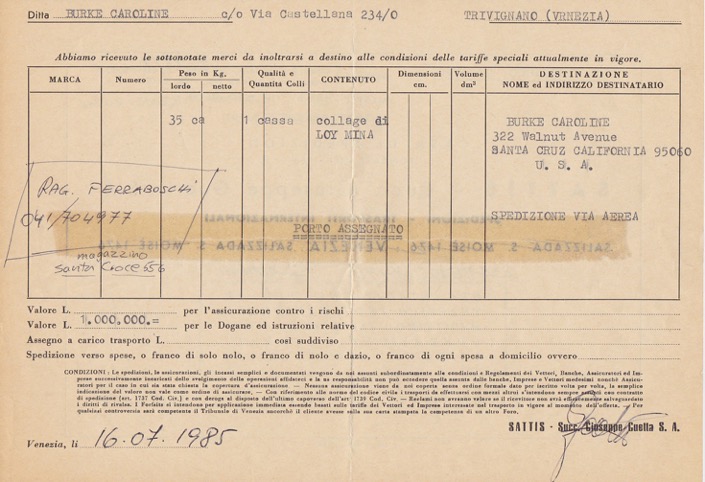

In 1985, when I was again in Paris, writing the book that would be published as Becoming Modern and seeking to interview anyone who knew her, I met Sindbad Vail, the son of Peggy Guggenheim and Lawrence Vail. Sindbad remarked dryly that after his mother’s death, he inherited everything from her collection that was of little or no value (the rest went to the Foundation). These items, including Househunting, were stored in his warehouse outside Venice. He encouraged me to go there and help myself to the Loy, then added that he had no idea of its condition since ‘vandals’ had ransacked the warehouse. He gave me the key. I made plans to go to Venice to see what was left of Househunting.

I started the trip at the Train Bleu, the restaurant at the Gare de Lyon where travelers to Venice and points southeast often begin their trips with a glass of champagne.

Once in Venice I made my way to Vail’s warehouse, in Mestre, an industrial center across the railroad bridge from old Venice. It looked unpromising, to say the least, from the outside.

Once I unlocked the door, it was even more depressing.

The “vandals,” according to Vail, family members intent on recovering anything of value, had gone through what remained there and in the process, damaged Househunting. I was all but undone. Nevertheless, I took the construction back to Venice and arranged for it to be held at a transport agency pending my decision about its future.

The owner of a damaged Mina Loy, I returned to Venice in 1986, having decided to rescue the piece despite its condition and the complexities of international shipping. A month later the piece arrived in its box at San Francisco airport and cleared customs as a worthless work of modern art, of interest to no one but myself.

Restoration, Northern California, 1986-1990

This was just the beginning. I had to find a way to restore the work I had become attached to despite, or because of its dilapidated state.

A friend directed me to the Achenbach Foundation for the Graphic Arts: they recommended Karen Zukor, a “conservator of documents and works on paper” in Oakland, who had worked on everything from Dürer prints to Chinese portraits on scrolls. She was up for the challenge. From her preliminary report: “All the elements are very brittle, weak and desiccated. The poor quality of the materials used (acidic cardboard, adhesives which age poorly, for ex.) have contributed to the overall deterioration…If the assemblage is conserved and/or restored all efforts will be made to retain a color balance overall; it will be kept in mind that the whole must be as harmonious as possible.”

It would take two years to finish the delicate work of restoration.

To aid in the process, I gave Karen Zukor the one photograph in my possession of a Loy construction from Aspen (formerly in the collection of her friend Goodie Taylor), to compare coloration, materials and overall treatment, although it was presumably put together after 1953.

Returning to work on the manuscript, it felt as if I now had a collaborator in my restoration project, the writing of Loy’s life.

This photo was taken after the removal of the central figure for cleaning, reattaching the crown, and the restoration of the other elements.

“It is astonishing how the addition of the head pulls the composition together,” Zukor observed at a later stage, when details such as the clothes on the line still needed her attention.

Zukor thought of giving a talk to her colleagues about her work on the piece. Its restoration had been “something of a triumph”—the means to salvage part of a life that had been “unusual…if fragmented.”

For me, Househunting holds many meanings. It is emblematic of the process of life-writing, the voyages backwards and forwards in time, the fortunate accidents of one’s encounters with documents, objects, and people, as well as the improbability of achieving completion or an harmonious whole despite one’s best efforts and unexpected moments of grace.

Coda

In some ways, Househunting is also an emblem of my peregrinations as a biographer, some of which I’ve tried to conjure for you today, and more generally, of my life as what we might call a serial expatriate. Like Loy, I have often moved house and country, and at times, been in fear or in thrall to the idea of being “unhoused.” Haven’t we all dreamed our own “househunting” dreams—domestic, vocational, artistic, spiritual—the contradictions of which still challenge us some one hundred years after Loy wrote in her 1914 Feminist Manifesto, “Forget that you live in houses that you may live in yourselves.”