In this section you can explore:

- Loy’s Criticism of Freud

- “The Library of the Sphinx”: New Models of Eros & Female Sexuality

- Eros Obsolete, “Lunar Baedeker,” and Duchamp’s Large Glass

- The Library of the Sphinx & Surrealism

- Surrealism & Maternity

Loy’s Criticism of Freud

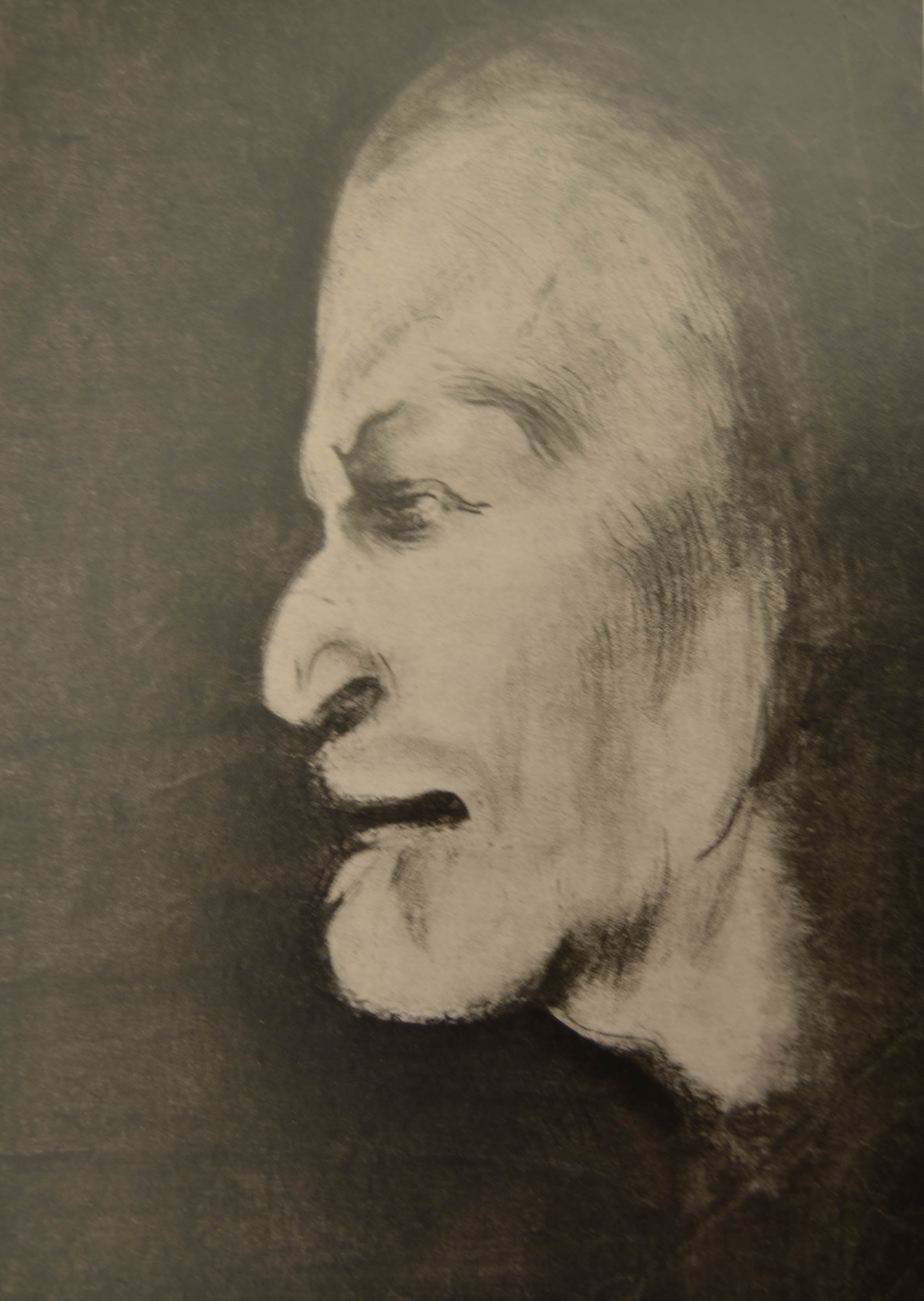

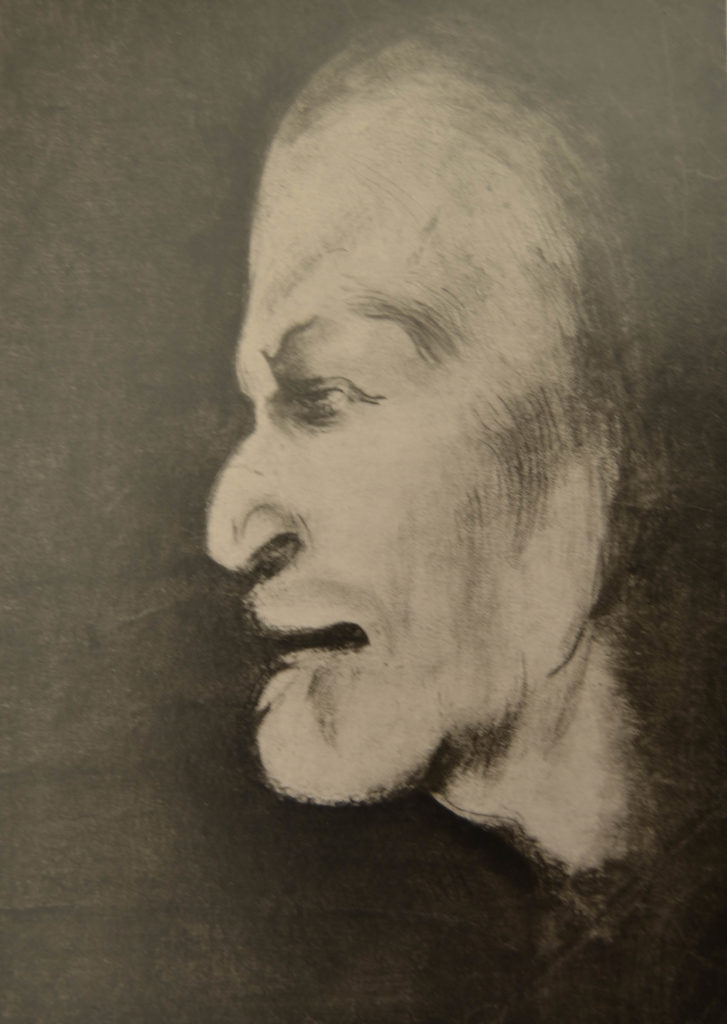

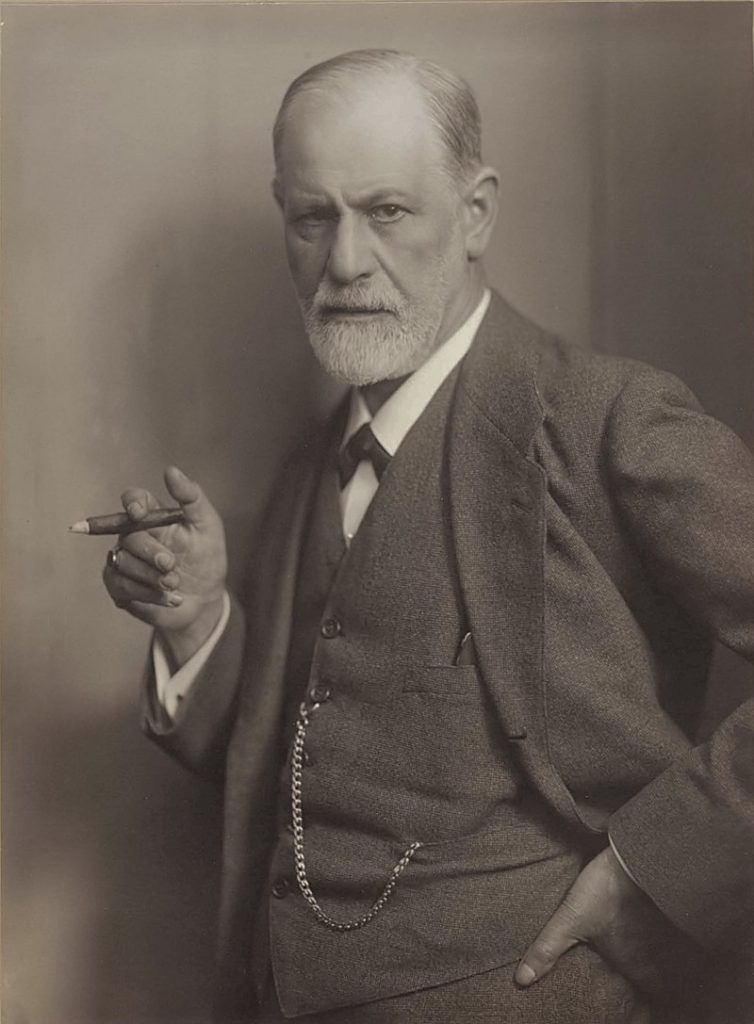

Loy had read Freud as early as 1910, possibly in the original German (Burke 119).1 She used Freudian language in her early poems and manifestos (she refers to the “subconscious” in “Parturition” and “subconsciousness” in “Aphorisms on Futurism”), and Freudian psychoanalysis was the “topic of choice” during Loy’s years (1916-1917) as part of the Arensberg circle in New York (Burke 214). She met Freud in Vienna in spring 1922, prior to moving to Paris; he read Loy’s stories while she drew his portrait and pronounced her story “Hush Money” as “analytic” (Burke 312-313). While Loy acknowledged Freud’s importance, from the 1920s onwards she would criticize Freudian theories.

Loy was not alone in criticizing Freudian thought and looking elsewhere for understandings of psychology, the unconscious, eros, and female sexuality (Chadwick 126). The painter Leonora Carrington turned to alchemy and Ithell Colquhoun to occult nature and myth (Chadwick 85, 105, 153). Melanie Klein and Joan Riviere (who worked with and translated the works of Klein and Freud, and was analyzed by Freud in Vienna in 1922), offered alternative models of childhood development and female sexuality that were influential at this time.

Loy felt that Freud limited the unconscious with his theories, but did not dispute the powerful role of the unconscious. As she commented in “Modern Poetry” (1925), “I believe that the quality of genius must be largely unconscious” (LLB96, 160). Like poet Elizabeth Bishop who was interested in Surrealism but skeptical of Freud, Loy was more interested in the unconscious as the realm of artistic creation than as the repository of repressed wishes and desires.2 She makes this point of view clear in her essay “Conversion,” subtitled “Critique / of D.H. Lawrence / Psychoanalysis / & the inconscious (sic)” (SE 375), and written in the 1920s in response to Lawrence’s 1921 book.3 Loy quickly establishes an analogy between the Catholic Church and Freudian analysis:

The obsessions prescribed by the Holy Church of Rome, are re-edited by the Psychoanalyst. / The Fathers and Freud successively established confessionals for neurotics, and it will not be long before they are fitted with domestic appliances (SE 227).

Catholic and psychoanalytic confession both invite the revelation of repressed or proscribed sexual actions and desires, with the aim of moral regulation on the part of the Church, and therapeutic recognition on the part of Freud.

Although divided by a secular gulf, both “the Fathers and Freud,” Catholicism and Psychoanalysis operate with rigid, patriarchal understandings of femininity and maternity. Just as Loy connects Freud to the church Fathers, she connects the Freudian “Eternal Mother” to the Virgin Mary, noting that “In psycho-analytic literature, at least, we are offered no escape from the post-natal womb of the Eternal Mother. / And the Eternal Mother devours her literary kittens —-invariably” (SE 227). As Catholics worship the Virgin Mary, so the psychoanalytic convert turns to his “mother complex” (SE 227).

Distinguishing her aims from those of the Catholic Church and Freud, Loy writes

The aim of the artist is to miss the Absolute —- the only possible creative gesture —- whereas the mystic impulse is to embrace a ‘ready-made’ in the way of absolutes / And the Absolute of this new mechanised mysticism of the Psycho-Analyst is the Unconscious. (SE 228)

Linking the Catholic God to the Freudian Unconscious as “readymade” absolutes, Loy implies that such concepts and the belief systems they engender are received mechanically. In “Aphorisms on Futurism” (1914) Loy referred to the “mechanical reactions of the subconsciousness, that rubbish heap of race-tradition –” (LLB96 152), suggesting that the critical mind must mediate this “rubbish heap.” Whereas artists like Duchamp and Loy transform the ready-made or mass produced object or idea, Loy implies that Catholic and psychoanalytic converts unthinkingly accept an already-defined “absolute,” shutting down spiritual and intellectual inquiry.4 Thus Loy accuses Lawrence as a convert to Freud of “dangerously damn[ing] his own creative flux with a theory” (SE 228). Theory renders static those forces elemental to creative flux (sexuality, the unconscious, desire).

Loy also felt that Freud was limited in his understanding of eros and female sexuality, arguing in “History of Religion and Eros” (dated by Burke to New York 1948-53) that

Freud is unnecessary to the future. His utile achievement lay in his solution of the problem, ‘To mention or not to mention.’ By making it, aided by the scientific aegis – – – fashionably polite to mention. Clearing a way out for inhibition.” (SE 252)

Suzanne Hobson argues that for Loy, “By over-intellectualizing and over-exposing the act of procreation, Freud had turned a mysterious life-force into a dogmatic duty” (Salt 252). Although Freud had helped to lift sexual inhibitions, Loy found his understanding of eros “blind”: “that terrain, exploited by his followers, is become an infinitely extensible maze of introversion in search of Eros – – – the little man who isn’t there – – – – -” (SE 252).

In naming Freudian Eros “the little man who isn’t there,” Loy belittles the search for an Eros defined by men, a search that preoccupied Surrealists such as Breton. As Whitney Chadwick observes

The cultivation of eros in Surrealism made woman into an active sexual force in the world and in man’s creative life, but the language of love, whether expressed in the romantic visions of Breton and Eluard or in the perverse images of Dali and Bellmer, was a male language. Its subject was woman, its object woman, and even while proclaiming woman’s liberty, it defined her image in terms of man’s desires. (Chadwick 103)

As Loy asks in “Faunfare,” “for is not / Eros / forever overall / a male?” (LLB96 128).

In her novel Insel based on Surrealist painter Richard Oelze, Loy’s protagonist Mrs. Jones comments “we had, in our ‘timeless conversation’ with Insel’s concurrence in my ‘wonderful ideas,’ superseded Freud” (166). In the late 1930s and 1940s Loy and her friend Joseph Cornell positioned Christian Science and its belief in thought as a healing force as an alternative to the Freudian unconscious and Surrealism’s “black magic,” a belief evident in Insel.5 Sarah Hayden reads Mrs. Jones’s “alternately solicitous and cruel policing” of Insel’s body as Loy’s response to the masculine and often misogynist treatment of eros by the Surrealists (Curious Disciplines 156).

Loy connects this misogyny to applications of Freud: in one scene Insel comments of Mrs. Jones’ lampshade design threaded with a coil of “shocking pink” that “It would surely be of the greatest interest to Freud” (166). Mrs. Jones comments acidly, “Out of this harmless even pretty object an ignorant bully had constructed for me, according to his own conceptions, a libido threaded with some viciousness impossible to construe. / I was astounded” (166-7) (See “Mina Loy’s lampshade shop” and on the Freudian fetish, “Surrealist Objects, Fashion, Design”).

“The Library of the Sphinx”: New models of Eros & Female Sexuality

The problem of eros — and of female sexual desire — interested Loy throughout her career and preceded her engagement with Surrealism.6 At the end of her “Feminist Manifesto” (1914) Loy had stated,

Another great illusion that woman must use all her introspective clear-sightedness & unbiased bravery to destroy — for the sake of her self respect is the impurity of sex the realisation in defiance of superstition that there is nothing impure in sex — except in the mental attitude to it — will constitute an incalculable & wider social regeneration than it is possible for our generation to imagine. (LLB96 156)

Although Freud had provided a rationale for the modernists to challenge sexual taboos, Loy found that her male contemporaries were operating under a number of illusions that prevented them from acknowledging women’s real sexual desires and experience. Loy would turn to Havelock Ellis and other sexologists for a fuller understanding of female sexuality than that offered by Freud.7 In “Havelock Ellis” Loy recounts a 1920 conversation with Ellis in which he told her that “Ninety percent of the women in England …found no pleasure in marriage” (SE 235), and Loy preferred Ellis’s realism to Freud’s theories and her contemporaries’ illusions.

In her essay “The Library of the Sphinx” likely written in the early 1920s, Loy tackles these illusions, taking inspiration from Havelock Ellis. In Loy’s essay the sphinx figures the representation of woman as she appears in writing by men, and whose actual experience thus remains veiled and enigmatic:

“Woman–” said Havelock Ellis to the sphinx, “put up with what she got and she got nothing!”

I dared not lose my literature — sobbed the sphinx — it was so lo-o-o-vely!

Your literature — let us examine it your literature —

It was written by the men– (SE 254)

Loy proceeds to examine work by Joyce, Frank Harris, D.H. Lawrence, and T.S. Eliot, and concludes that

Practically the whole of our psychological literature written by men might be lumped together as the unwitting analysis of the unsatisfied woman. (SE 257).

She skewers the inaccuracy of these writers’ sex scenes and their “one-sided” portrayals of women:

IF our erotic, romantic, and realistic literature has presented the gentle reader with an interminable procession — of ladies ‘possessed’ in floods of delight — the instantaneous beatification of the female by the (always) condescending male — where may we ask did those authors live? In some sublime refuge from our daily life? (SE 256)

Eros Obsolete, “Lunar Baedeker,” and Duchamp’s Large Glass

Loy’s 1923 poem “Lunar Baedeker” explores the “library of the sphinx” with a critical eye, figuring it as a lunar landscape defined by “Eros obsolete” (LB96 82). Loy’s poem alludes to the avant-garde scenes in New York, Berlin, Florence, and Paris, but distorts and transforms them through the lens of the poetic imagination. The lunar landscape is simultaneously real and fantastical, geographical and literary, allowing Loy to engage critically with the avant-garde’s depictions of eros while breaking new aesthetic ground.

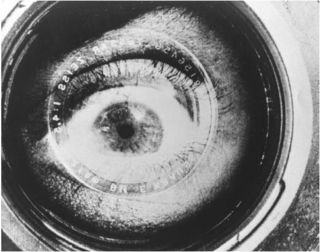

Duchamp’s proclamation “Eros, C’est la vie” and his appearance in Man Ray photos from the early 1920s as his feminine alter-ego Rrose Selavy (a pun on “Eros, C’est la vie”) indicated that the landscape of gender and eros was ready to be re-made.

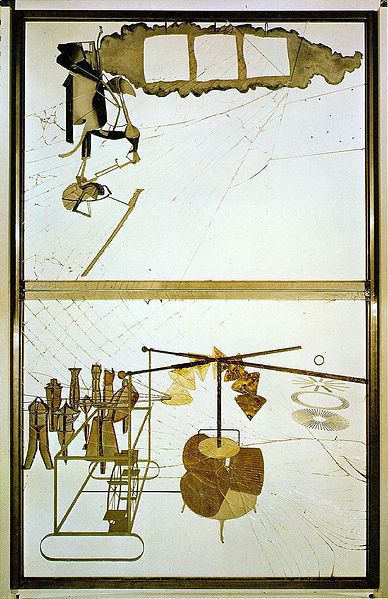

Although Duchamp and the male avant-garde remained largely preoccupied with the masculine experience of eros, Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, known as the Large Glass, which Loy had visited as part of the Arensberg circle in New York as early as 1917 (Burke 228), proved generative to a number of women.8

In dividing the Bride from her prospective mates by placing her in the top half of the Glass, Duchamp set in motion a spatialized “plot” involving heterosexual desire and a frustrated romance. Duchamp’s Bride, both positioned within but also resistant to the plot of heterosexual desire and feminized spectacle, could be written over by women who were redefining readymade gender roles in their own works and lives. The abstract and mechanical qualities of Duchamp’s Bride and Bachelor allow them to “defy traditional gender qualifications” (Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp 71). In describing the Bride both as an “apotheosis of virginity” and as a “new motor,” who is stripped nude by the bachelors but whose own “desiring” generates a “stripping voluntarily imagined” (Notes 22, 24), Duchamp presents conventions of masculinity and femininity as ready-made clichés that mechanize our habits, but which can also be ironized, suspended, and performatively remade.

The Glass’s refusal of consummation coupled with its resistance to the Bride’s visual allure creates a “Delay in Glass” (Notes 42), inviting an intellectual, verbal engagement (Judovitz, Drawing 40-41). In 1934 Duchamp published La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même (commonly known as the “Green Box),” a collection of notes (begun in 1912) about the Glass, and in his words, “the final product was to be a wedding of mental and visual elements” (Tomkins, Duchamp 296). The pun on wedding reveals that the only marriage of Bride and Bachelors would be a conceptual one, involving the play of word and image.

As I argue in Dada/Surrealism, the Large Glass’s creation of an active role for the spectator proved generative to many women who were interested in establishing new models of producing, displaying, and consuming avant-garde art. Taking up the invitation of the Large Glass, and often taking on the role of Duchamp’s Bride, women such as Loy used their position on the margins of both the museum and the avant-garde as an impetus to reimagine both, and in doing so, to comment variously on institutional power, the practices of surrealist display, and gendered modes of looking. In their responses to and reframings of the Large Glass, Loy and others contribute to a mobile, poetic museum built from mixtures of media and the transformative power of the spectator’s imagination.

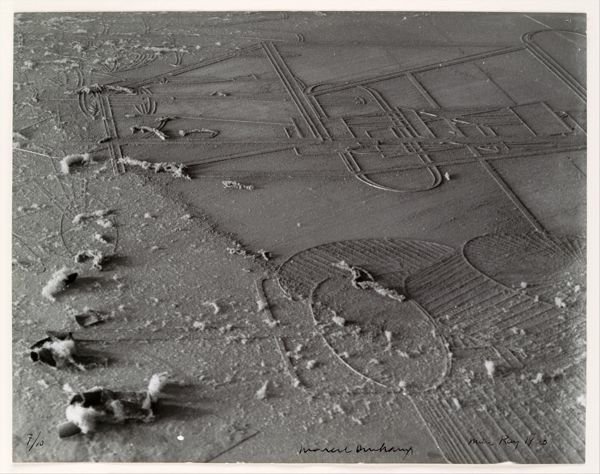

While the poem “Lunar Baedeker” invites many kinds of readings and interpretive models (see “Return to New York” for a different approach), reading the poem as a response to Duchamp’s Large Glass illuminates Loy’s depiction of “eros obsolete.” Just as Man Ray’s “Dust Breeding”, a photographic close-up of dust on a section of Duchamp’s Large Glass transforms the glass into a strange new landscape, Loy’s “Lunar Baedeker” transforms the Glass into the surface of the moon:

Cyclones

of ecstatic dust

and ashes whirl

crusaders

from hallucinatory citadels

of shattered glass

into evacuate craters (LLB96 82)

While Duchamp’s bachelors experience a frustrated desire for the bride, Loy’s landscape is completely drained of eros and the colors that conventionally signify sex, passion, and fertility: the red-light district becomes the “eye-light white-light district of lunar lusts.” Rendering her lunar landscape in photographic tones of black and white, Loy may allude to Man Ray’s photo and/or the ways in which film, photography, and photomechanical reproduction mediate and delay sexual desire, also a theme of the Large Glass. But she may also reflect on the lack of room for female desire in the works of the avant-garde.

In Loy’s lunar landscape women’s presence is restricted to outmoded, cliched depictions of desirable women as imagined by the European tradition:

in the oxidized Orient

Onyx-eyed odalisques

and ornithologists

observe

the flight

of Eros obsolete (LB96 82)

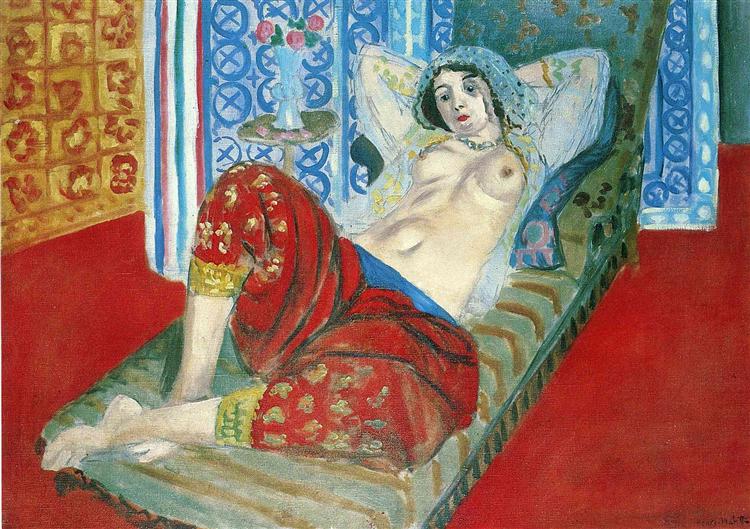

Notably, Eros has vacated the scene. Loy’s “odalisques” from the “oxidized Orient” — referring to female slaves or concubines in a Turkish harem — connote the worn-out or “oxidized” Orientalism of a European tradition that had long conflated female sexual allure with racialized others, a tradition that shaped modernism, notably Matisse’s paintings of odalisques (1917-1930).

Loy concludes her poem by reflecting on the clichéd figure of the feminized moon as rendered in the poetic and artistic tradition:

‘Crystal Concubine’

— — — — — — —

Pocked with personification

the fossil virgin of the skies

waxes and wanes — — — — (LLB96 82)

Either “concubine” or virgin, the representations of the moon in the “library of the sphinx” are tied to outmoded gender roles and binaries (mistress/mother, whore/virgin) that deny and erase female eros. Loy’s dashes figure the moon’s pocking and waning, even as they visually create a space in the lunar landscape for new language and new thinking about female desire to emerge.

The Library of the Sphinx & Surrealism

Loy’s “Library of the Sphinx” explores the treatment of sex in the Anglo-American tradition but would also resonate with the works of Surrealism. Alyce Mahon argues that for the male Surrealists, “The myth of the sphinx was especially attractive, providing the perfect metatext for an exploration of forbidden desire, as well as encompassing the fantasy of the femme fatale, the potential of the city for the marvelous encounter, and a means of self-questioning by which logic and riddle could be set against each other” (Dada/Surrealism). Mahon considers the gendered treatment of the sphinx by Breton, Ernst, Dali, and Freud, and concludes that “the sphinx and modernity were aligned as they were perceived as sharing an element of seduction and threat. Woman’s presence in the modern city became problematic – as we find with Breton’s Nadja, her status was often suspect, poised between prostitute and fallen woman.”

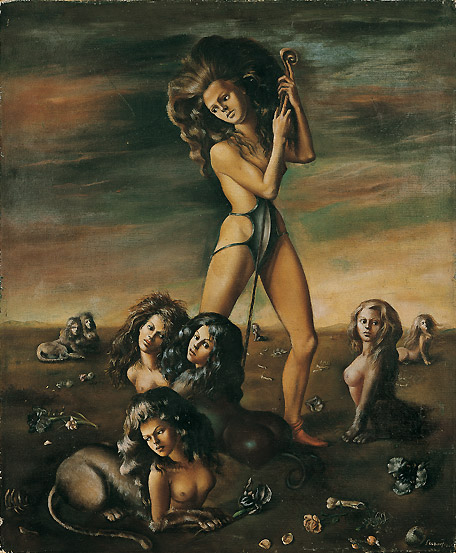

Like Loy, the female surrealist painter Leonor Fini was interested in the sphinx and sought to imbue this creature with new meaning in a critical deparature from the work of the male Surrealists. Alyce Mahon argues that in Fini’s paintings “a different sphinx is found, one who stands as a mistress of riddles but also as a guardian of life. Fini presents a peculiarly Egyptian sphinx, expanding the sphinx’s mythology for surrealism so that the feminine denotes humanism rather than the simple threat of death. Fini’s paintings emphasize the regenerative power of the sphinx and her ability to return the individual to his/her primordial nature.” The sphinx’s mixture of human and animal, male and female interested Fini, and perhaps also Loy, who would create mixed, hybrid creatures in her paintings, objects, and poems of the early 1930s. Loy likely crossed paths with Fini in Paris, given that the painter Richard Oelze (who Loy would portray in fictionalized form in her novel Insel), asked Loy in a November 1936 letter to let him know whether Fini was still in Paris, as he was hoping to contact Fini to return a small picture of his.9

Surrealism & Maternity

Coupled to the masculine, heterosexual definition of eros in Bretonian Surrealism was the vexed status of maternity in Surrealist circles; Surrealists associated motherhood with bourgeois values and a de-eroticization of the mother, and very few female Surrealists in the early decades of the movement had children (Chadwick 130). Loy’s experience of and thinking about maternity diverged from that of the Surrealists and Freud. When Loy moved back to Paris in 1921 she had already given birth to four children, and her time in Florence and contact with the Futurist movement had shaped her radical revisioning of maternity (See “Firenze is a Woman”). As she had argued in her Feminist Manifesto (1914) “The first illusion it is to your interest to demolish is the division of women into two classes the mistress, & the mother” (LLB96 154). Loy scathingly critiqued the sexual double standard that divides mother from mistress, and worked to uncouple maternity from the economic “bargain” of marriage. Alex Goody argues that Loy’s representation of the maternal body in her 1925 autobiographical sequence Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose responds to and reworks Freud’s 1922 The Pleasure Principle (“Empire, Motherhood, and the Poetics of the Self”).

Loy’s efforts to forge a career as an artist and mother informed her own treatment of maternity in both her writing and painting, but maternity also signified a nexus of gendered, cultural, religious, and economic concerns that would continue to interest her in Paris and New York. For instance her sculpture “Maternity” (1935) dates to her final year in Paris and resonates with documentary photos from this time such as those by Dorothea Lange and Doris Ullmann (LLB82), perhaps anticipating her interest in documentary in New York (Kinnahan, Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography).

- The first translation of Freud into English was Studies in Hysteria, translated by A.A. Brill and published in 1909; see G.G. Meynell, “Freud Translated: An Historical and Bibliographical Note.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 74 April 1981. Freud’s Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis, delivered at Clark University in Worcester MA in 1909, were published in 1910 in English.

- As poet Elizabeth Bishop wrote Marianne Moore in September 1937 from Paris regarding her reasons for avoiding Freudian psychoanalysis, urged on her by Bryher, “…everything I have read about it has made me think that psychologists misinterpret and very much underestimate all the workings of ART! ‘Psychoanalysts do not see the poet playing a social function, but regard him as a neurotic working off his complexes at the expense of the public. Therefore in analyzing a work of art, psychoanalysts seek just those symbols that are peculiarly private, i.e. neurotic, and hence psychoanalytical criticism of art finds its examples and material always either in third-rate artistic work or in accidental features of good work.’ This is from Illusion and Reality by Christopher Caudwell– have you seen it? It is a very confused, uneven kind of book, but nevertheless, very worthwhile, I think” (One Art 63).

- Sara Crangle notes that Lawrence’s Women in Love, referred to in the essay, was published in 1920, and that Mary Pickford (also mentioned in Loy’s essay) was famous from 1910 – 1930 (SE 376). Suzanne Hobson dates the essay between the mid-1920s and 30s (Salt 249). Hobson’s insightful essay discusses “Conversion” at length, as a means of illuminating the “profane religion” of Loy’s poetry (Salt).

- See also Steve Pinkerton’s insightful analysis of Mina Loy’s blasphemous conflation of sex/eros, religion, and Christ in her late work. Pinkerton argues that Christ “is the fleshly tie that binds ‘Religion and Eros’ in Loy’s formulations, because ‘the Flesh,’ in the case of both the religious and the sexual, is the ‘instrument’ of the body’s access to the divine” (57). Thus sex becomes “sacred by Loy’s standards, to much the same extent that it is profane by orthodox standards” enabling “a divine merging that Loy charges Christian dogma itself with defiling in its war against the flesh'” (58).

- In Insel Loy’s protagonist Mrs. Jones asks Insel “Are you one of those surrealists who have taken up black magic?” (42) and states “there’s something fundamentally black-magicky about the surrealists…It’s funny how people who get mixed up with black magic do suddenly look like death’s heads– they will grin and there is nothing but a skull peering at you, at once it’s all over — but you remember” (21). Andrew Gaetdke reads Insel as an analysis of Insel that subjects the psychoanalytic case study to radical ethical critique. On the importance of Christian Science to Loy’s novel Insel, see the essays by Tim Armstrong (Salt 204-220) and David Ayers (Salt 221-247). See too Sarah Hayden’s treatment of Insel in the context of Christian Science in her recent edition of Insel and in Curious Disciplines. On Loy and Christian Science see also Lara Vetter, “Theories of Spiritual Evolution, Christian Science, and the ‘Cosmopolitan Jew’: Mina Loy and American Identity.” Journal of Modern Literature 31.1 (2007): 47-63.

- In the 1910s and 20s female experimental artists including Loy, the Baroness, and Claude Cahun opened up explorations of femininity, masculinity, and sexuality, departing from the narrow confines of middle-class patriarchal culture and the depictions of female sexuality in the masculine avant-garde. Loy’s Songs to Joannes is perhaps the best example of Loy’s frank engagement with sexuality. Irene Gammel singles out the Baroness, Loy, Barnes, Stein and Millay as those who “vigorously pushed the boundaries of female sexual expression in poetry” (Baroness 9-10), writing that the Baroness “tore down post-Victorian gender codes by poeticizing decidedly unpoetic subject matter, including birth-control devices such as condoms…, sex toys…, and specific sex acts including oral sex…” (Baroness 9).

- See Paul Peppis, “Rewriting Sex: Mina Loy, Marie Stopes, and Sexology” Modernism/Modernity 9.4 (November 2002).

- Duchamp worked on the Large Glass from 1912 to 1923, starting the Notes in Paris and continuing work on the Glass after his move to New York in 1915 and declaring it “definitively unfinished” in 1923. A selection from the Notes was published in English translation in the Surrealist Number of This Quarter (1932) edited by Breton.

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 6, Richard Oelze Folder, and Notes on Mina Loy’s Correspondence Folder.