Nella Larsen, avant-garde? Modernist, yes, but avant-garde? Her writing is hardly in the vein of a Gertrude Stein or a Djuna Barnes. So linear, so easy to consume. Surely she can’t be comfortably housed with the co-hort we’ve come to call “avant-garde.”

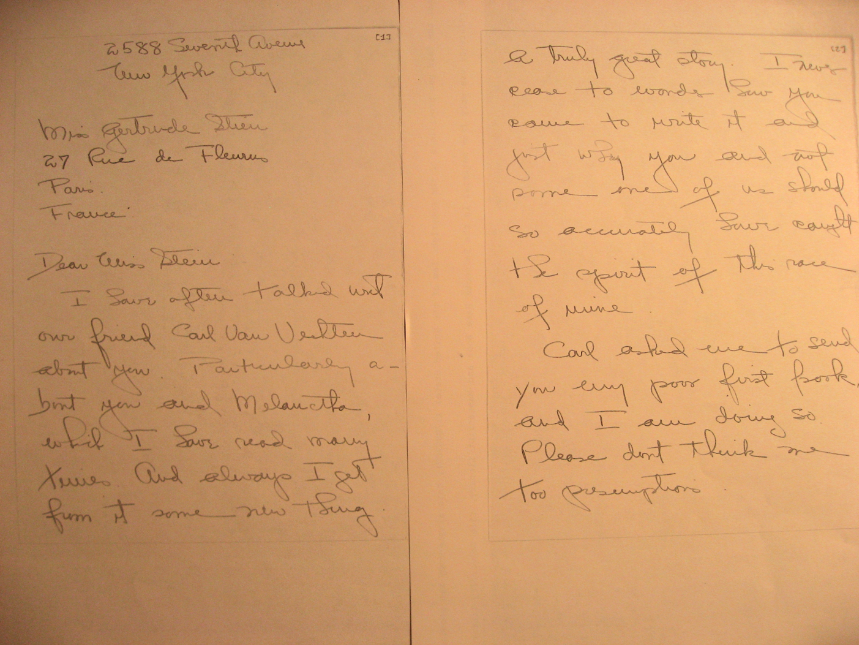

In an effort to add more black women to my course on the feminist avant-garde, I include Nella Larsen, along with contemporary poet Harryette Mullens, reading both alongside Gertrude Stein. I introduce Larsen’s Quicksand by way of a letter she wrote to Stein praising “Melanctha.” She has read “Melanctha” many times, she writes, and always gets from it “some new thing.” What did she get from Stein?

To read Larsen’s novel alongside Stein’s is to see its estrangement from realism in its apparently realistic style. Its repetition with variation, its presentation of experience over event, its expression of the emerging interiority of a young black woman. Like Melanctha, Helga wanders; like Melanctha, Helga desires something inchoate. Like Melanctha, Helga “could neither conform, nor be happy in her unconformity.” Neither woman has a home. Home, with its connotations of stasis and permanency, does not fit the time-sense of the twentieth century as Stein saw it. Larsen’s novel ends not with a resolution but with the endless repetition of the same.

Quicksand is a quintessentially modernist novel in other, more familiar ways: its urban settings, its nightclub scenes, its references to jazz, its fashion sense. Larsen immerses us in the everyday life of Chicago, Harlem, and Copenhagan: the crowded city streets, the advertisements in the shop windows, the rush of taxi cabs, the oppressive noise and odor. But it is less in the “fabric of things” (Virginia Woolf’s phrase) that Larsen’s novel feels modernist than in Helga’s, and the narrative’s, self-conscious awareness of the moment, of its “being seen.” We are not just watching the scene before us but we are aware that we are watching, as in a movie. Larsen’s use of free indirect discourse exposes Helga’s mindfulness of her own position as an onlooker, of and apart from the scene, en dehors.

Larsen can no longer look at the world the same after reading Stein. Stein gave her the temporality of the moment, the heightened mediation of what is happening everyday. If Stein captured “the spirit of this race of mine,” as Larsen writes in her letter, Larsen does so anew, apprehending the fleetingness of the interval, that moment between old forms of representation and the possibility of something new, en dehors the avant-garde.

En dehors garde works beautifully as a way to argue not for the inclusion of writers like Larsen in the historical avant-garde, but for the contribution they make by turning away from it, or writing alongside of it. I can no longer look at Stein the same after reading Larsen.