The term “avant-garde,” derived from the “advance guard” of an army, emphasizes the militant, oppositional stance of the early twentieth-century art movements it came to describe. The Oxford English Dictionary defines avant-garde as:

- The foremost part of an army; the vanguard or van.

-

The pioneers or innovators in any art in a particular period.

- 1910 Daily Tel. 1 July 14/6 The new men of mark in the avant-garde.

The OED’s first recorded usage of avant-garde in relation to the arts emphasizes masculine virility: the “new men of mark” were remarkable and visible because they stood at the forefront of culture. Implicitly white and able-bodied, they could make a mark by opposing cultural institutions because they had cultural power.

Today, avant-garde is colloquially applied to anything new or experimental, especially in the arts. Scholars use the term historical avant-garde to refers to early twentieth-century, European, predominantly white, male-dominated art movements such as Futurism, Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. These experimental movements opposed bourgeois values and tastes, seeking to challenge and shock their audiences. They chronicled their exhibitions, publications, and performances, generating their own heroic histories and archives. Although women played major parts in the historical avant-garde, they tend to be omitted from its definitions, histories, and theories.

Mina Loy offers a case in point. Just as her career does not conform to linear narratives, so her life and work do not fit neatly into theories and histories of the avant-garde. She participated in nearly every avant-garde movement of the early 20th century—including Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism—yet was contained by none. “She was the avant-garde poster girl,” notes Cristanne Miller, “seen in her work, her appearance, and her life to represent the arts, the movement, and the times.” 1 Yet whereas scholarship on Loy almost invariably mentions her participation in international avant-garde circles, studies and anthologies of Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism rarely include Loy.

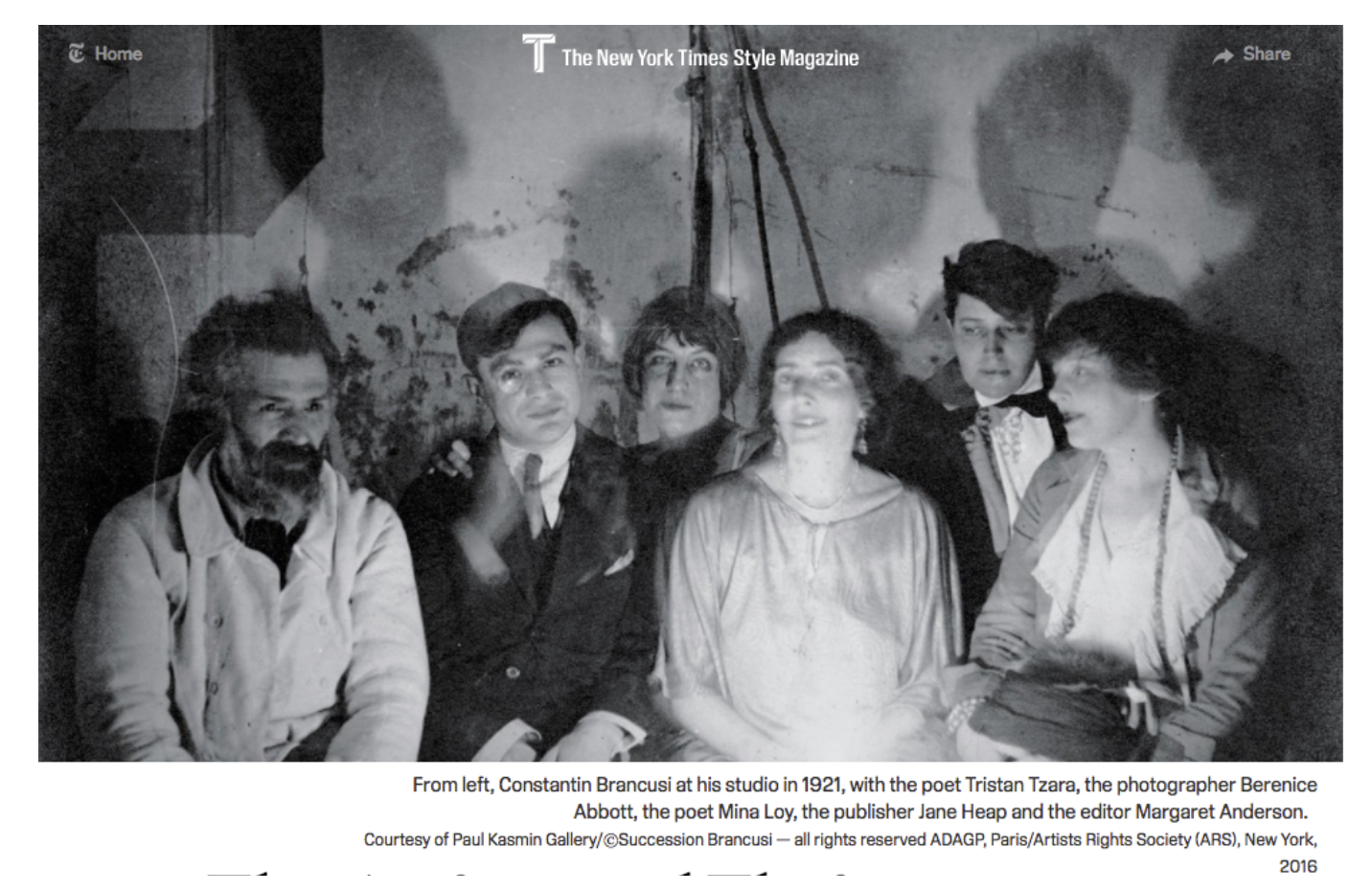

Take, for example, this archival photograph, published in the New York Times Style Magazine in 2016, nearly a century after the moment it records. The photograph depicts an avant-garde gathering in Constantin Brancusi’s Paris studio in 1921 (from left to right: the artist Brancusi, Dadaist and poet Tristan Tzara, the photographer Berenice Abbott, poet and artist Mina Loy, Little Review publisher Jane Heap, and Little Review editor Margaret Anderson). As reproduced in Style Magazine, this iconic photograph typifies Mina Loy’s position in the avant-garde. She is a central, animating, illuminating presence, yet she is also a ghostly spectre, mentioned only in a caption and never in the article.

Mina Loy’s position is representative of women in the historical avant-garde. Although women played major parts, they have been relegated to supporting roles in its lore—posed in a photograph, mentioned in a caption, or deposited in a slim folder in the archive of a celebrated male associate. While Marcel Duchamp’s role as an avant-garde provocateur who was central to several movements but who resisted strict affiliation with any particular movement has been amply chronicled and celebrated, Loy’s similar role and trajectory, fueled by her feminist perspective, has contributed instead to her marginality. Loy’s interest in avant-garde experiment was shaped by feminism, gender, and sexuality, and led her to self-consciously assume a position on the margins of avant-garde movements. Her ambivalent stance of interested but critical, feminist detachment typified the relationship of many women to the historical avant-garde, who did not fit comfortably in existing roles.

For women artists, working in the margins often offered an escape from oppressive conventions of femininity and masculinist standards of achievement. As James Martin Harding explains, “performance in the margins can legitimately be characterized as a site of resistance against the compromises and acquiescences to the normative values that are demanded in the mainstream.”2 But self-conscious marginality runs risks of obscurity and neglect, especially for women: “However romantically or idealistically conceived, the margins are less a site of choice than of exile” (Harding 4). The word neglect comes from the Latin “neg-” and “-legere,” meaning to be unread, which has too often been the fate of women writers.3

- Cristanne Miller, Cultures of Modernism: Marianne Moore, Mina Loy, & Else Lasker-Schüler: Gender and Literary Community in New York and Berlin, p.18, University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- James Martin Harding, Cutting Performances : Collage Events, Feminist Artists, and the American Avant-Garde, p.3, 1st pbk. ed., 1st pbk. ed., University of Michigan Press, 2012, Project Muse, Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

- Thanks to Stephen Ross for making this connection in his Hypothesis annotation, 5 April 2015.