In the summer of 2018, we conducted an experiment.

We wanted to develop a feminist theory of the en dehors garde—a term we coined to account for women, people of color, and others who have been excluded or marginalized in histories and theories of the avant-garde.

We didn’t just want to propose a new theory, however; we wanted to generate theory in a new, collaborative way.

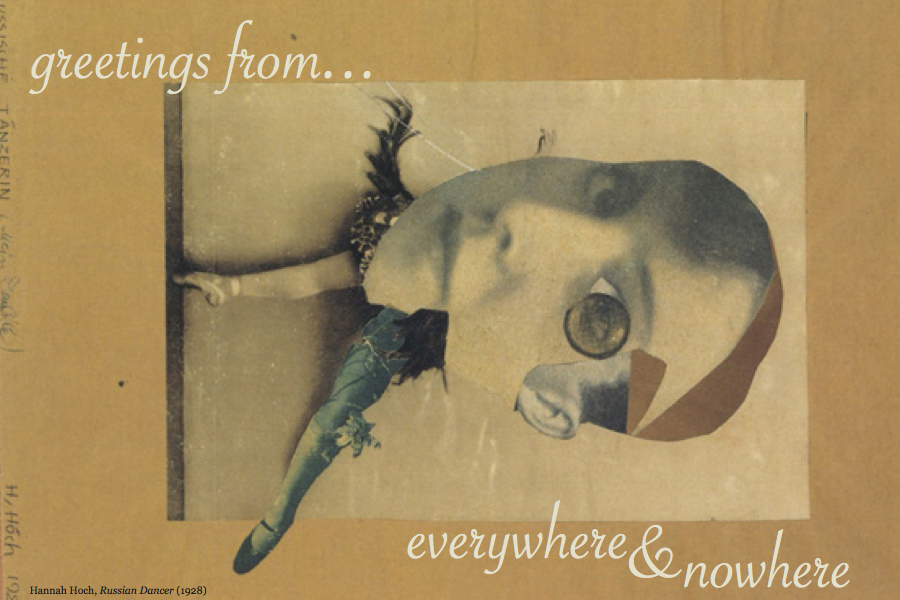

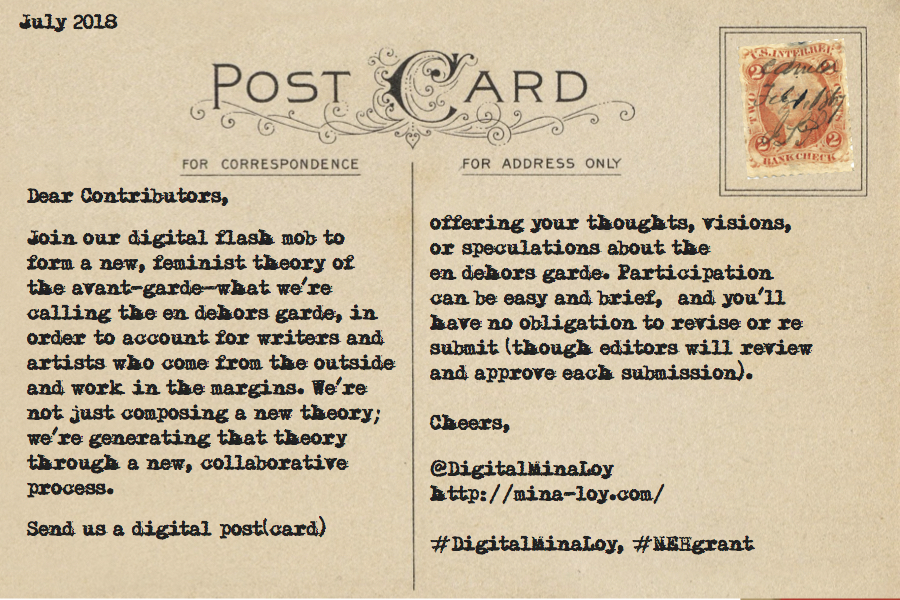

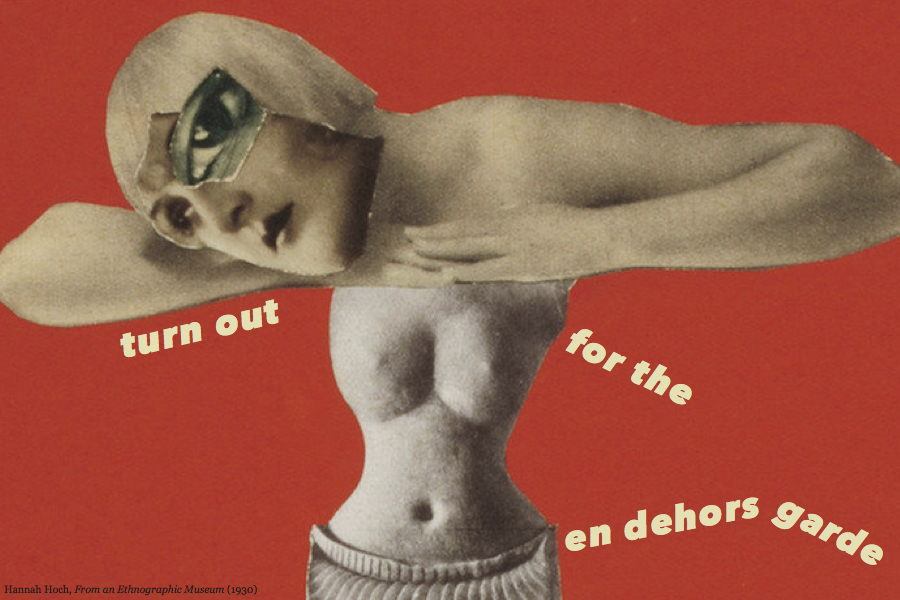

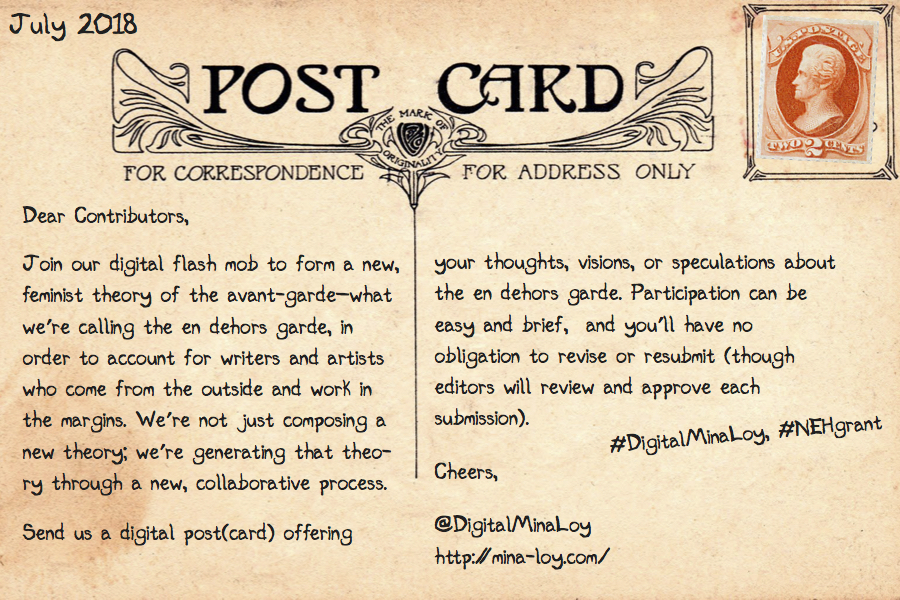

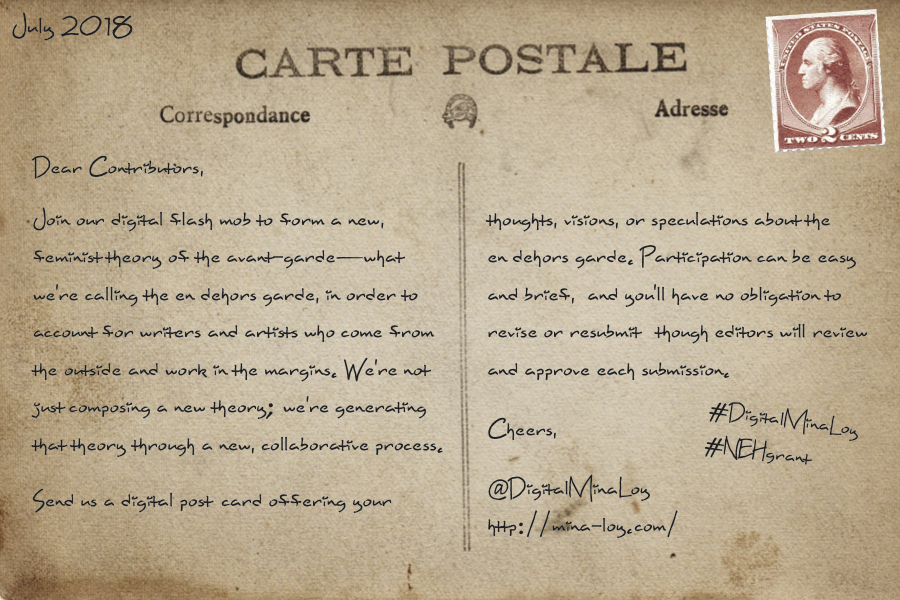

So we orchestrated a digital flash mob, inviting scholars, students, artists, writers, and the interested public to submit digital post(card)s expressing their ideas about the en dehors garde. Contributors could sign their names, adopt pseudonyms, or remain anonymous, and no prerequisites or qualifications were required. Answering Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s recent call for “generous thinking” in the humanities, we asked contributors to “think with” us and participate in the ongoing work of reimagining the historical avant-garde as a more inclusive en dehors garde.

Read the Original Flash Mob Invitation

We received 70 post(card)s from the U.S., Canada, UK, and France, and watched our site stats grow from a monthly average of fifty to a record high of 4,450 in September 2018. The post(card)s we received are displayed in a random grid. You can read, select, and arrange the post(card)s to compile your own, customized theory of the en dehors garde, exporting the results as a PDF. In this way, you can participate in the ongoing production of feminist theory.

Via this production process, theory is not a static, unified, or finished argument, but a plural, elastic, and ongoing process. Our method is feminist in its collaborative, decentralized structure, which defies the expectation of a single authority or unified argument.

Yet the process of selecting and arranging post(card)s may not be so different from what we do when we read what we typically think of as theory—dense, complex, abstract arguments. When we grapple with that kind of theory, we typically underline the passages that we deem most important and rearrange them according to our own interests, often combining them with other texts. Our method simply makes the process of selecting and arranging more tangible and explicit, so that readers may become more conscious of their active role in theorizing.

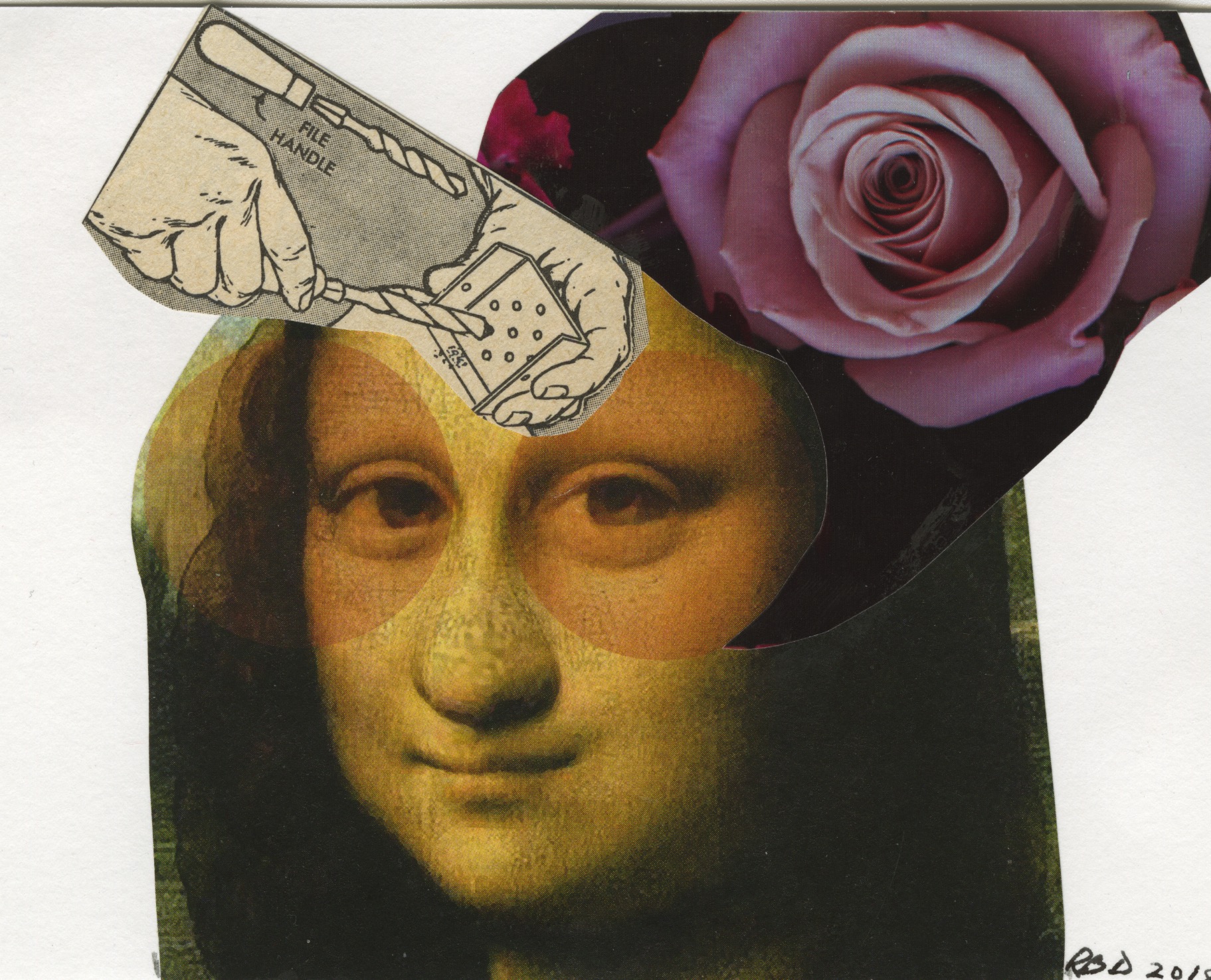

Despite the success of the “flash mob,” the experiment did not produce anything resembling theory as we know it. Few post(card)s take the form of “position statements” that can be assembled into any kind of coherent theory. The most popular form of submission was collage. The popularity of the collage form indicates our readers’ desire to become creators—not to theorize as a purely intellectual activity, but to theorize as a creative act and an intellectual intervention.

Of course, collage is also a key practice of the historical avant-garde, initiated by the Cubists and adopted by Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Romare Bearden, and others in an effort to disrupt conventional ways of seeing and knowing. As Marjorie Perloff explains, the term collage “comes from the French verb coller and refers literally to ‘pasting, sticking, or gluing,’ as in the application of wallpaper. In French, collage is also idiomatic for an ‘illicit’ sexual union, two unrelated ‘items,’ being pasted or stuck together.”1 James Martin Harding argues that the subversive power of collage gives it “amazing potential for structured feminist dissent and resistance to the hierarchies of male privilege,” making it a preferred form for avant-garde women artists.2

There is something daring about collage, which enables the juxtaposition of disparate objects in order to generate surprising patterns and unorthodox compositions. The form issues a a double shock:

1) Collage challenges the basic tenets of realistic representation in Western art.

Collage no longer offers a window to reality, it breaks the window to create its own reality.

For collage typically juxtaposes ‘real’ items–pages torn from newspapers, color illustrations taken from picture books, letters of the alphabet, numbers, nails–with painted or drawn images so as to create a curiously contradictory pictorial surface. For each element in the collage has a kind of double function: it refers to an external reality even as its compositional thrust is to undercut the very referentiality it seems to assert. And further: collage subverts all conventional figure-ground relationships, it generally being unclear whether item A is on top of item B or behind it or whether the two coexist in the shallow space which is the ‘picture.’ (Perloff, “Collage and Poetry”)

2) Collage subverts conventions of gender and sexuality.

According to Carolyn Burke, Stein and Picasso would have been well aware of the slang meaning of collage as an illicit sexual union; in the early 1910s, “both artists were living in differently choreographed but equally unconventional ‘menages a la colle,’ they must have been amused by the wit implicit in the new term for what Stein would later call ‘the modem composition'” (“Getting Spliced” 103). Stein, Loy, and other modernist women writers embraced collage poetics as a way of subverting gender and sexual norms, and modeling other patterns of union and intercourse, in which it’s not always clear who or what is on top:

As practiced by Stein, Loy, and [Marianne] Moore, the poetics of collage is flexible enough to express homosexual, heterosexual, and asexual models of the links between sexuality and writing. (Carolyn Burke, “Getting Spliced: Modernism and Sexual Difference,” American Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 1, 1987, p. 115., doi:10.2307/2712632.)

As James Harding argues, collage offers an “aesthetics of dissonance” which can be used to express dissidence, particularly feminist dissent. Techniques of parataxis and juxtaposition may be deployed to flatten hierarchies of meaning and value. The form is “cutting edge” not only in being associated with the “vanguard of artistic experimentation,” but also in the sense of “edges openly cut and spliced together in collage’s candid acknowledgment of the constructedness of its images” (Harding 24). Thus, according to Harding, collage offers not only a mode of feminist artistic expression, but also a model for feminist historiography, one that calls attention to the constructedness of histories of the avant-garde (Harding 25).

Why was collage the preferred form for our flash mob contributors? Were contributors aware of its potential to subvert hierarchies and pattern new, unorthodox relationships? Or was this form, which became dominant in the early 20th century, and has been enabled by digital technologies, an expedient choice? Were contributors inspired by the “postcard” form and its mixture of word and image? By Mina Loy’s crossing of verbal-visual boundaries? Did collage appeal as a way to juxtapose past and present, connecting the historical avant-garde to contemporary thoughts about the en dehors garde?

We see no need to privilege or exclude any of these possibilities. And while we have embraced an inclusive approach in gathering, presenting, and reflecting on the post(card)s (the only submissions we rejected were those that failed to supply citations for borrowed images), we are aware of the limitations of our experiment—its potential complicity with structures of privilege and exclusion.

Paranoid about continuing the exclusionary history of the avant-garde, the feminist avant-garde realizes its complicity with an inability to be entirely outside of patriarchal structures and compensates by dispersing editorial authority into the hands of the contributors.3

Despite our broad and open calls for participation on social media, many of our contributors were white women. While we tried to cast a wide net, we were most successful in activating a feminist network of scholars, artists, and writers, many of whom, like us, are associated with college and universities.

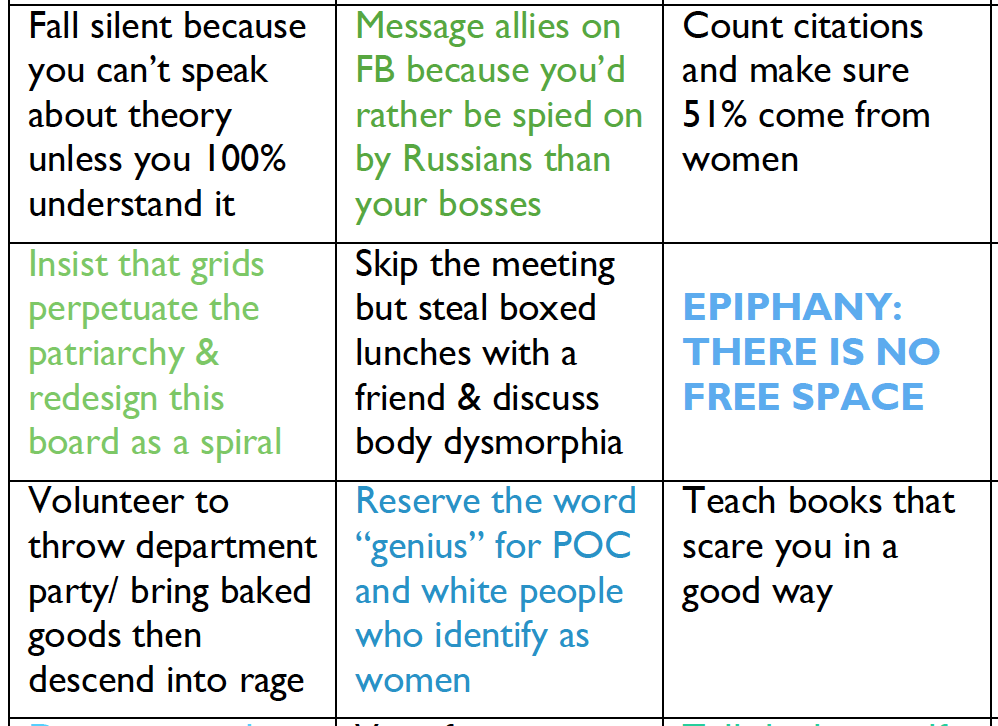

In addition the grid display, necessitated by the logic of HTML code, confines post(card)s within a rigid framework—a worry Lesley Wheeler articulates (and satirizes) in her “En Dehors Garde Bingo” post(card): “Insist that grids perpetuate the patriarchy & redesign this board as a spiral.”

In designing the display we offset the hierarchical effects of the grid by randomizing where the postcards appear, so that every time the page loads, post(card)s appear in a different order. In this way, no single post(card) gains priority or dominates the ever-changing formation.

Our en dehors garde experiment seeks to activate what Sophie Seita calls “a feminist politics of the forum, which aims for hospitality and non-hierarchical dialogue in avant-garde communities” (Seita 165). Like the feminist avant-garde magazines of the 1980s, ’90s, and ’00s magazines that Seita analyzes—HOW(ever), Chain, HOW2, M/E/A/N/I/N/G, and Raddle Moon—our flash mob aimed to create an open forum in which divergent points of view and heterogeneous materials were welcome. Whereas those magazines enacted “an alternative mode of forming literary communities that was deliberately more provisional and hospitable than in traditionally defined avant-garde groups (defined usually by their key players, key characteristics, and clear group boundaries)” (Seita 167), our experiment activates an alternative mode of forming theory that is deliberately more provisional and hospitable than traditional, single-authored theories of the avant-garde (defined usually by their key players, key characteristics, and clear group boundaries).

Ultimately, our digital flash mob’s failure to produce “theory as we know it” may be the mark of the experiment’s greatest success: it invites us to think of theory in new ways, and to recognize that our feminist theory of the en dehors garde resides in the process rather than the product. As Stephen Ross points out in his public peer review of the site,

…the intention was never to produce theory as we know it now, but to allow the aesthetic and the theoretical to inter-implicate and generate… For poesia [poetry] and theoria [theory] to coller [join] in an unsanctioned but passionate embrace so that we can see how the aesthetic theorizes and theory aestheticizes. Loy’s poetry is theory, her practice a theory of the avant-garde/en dehors garde. Why not let it teach us how to think it?4

Rather than authoring a conventional theory, we initiated a new process of theory making, in which the aesthetic and theoretical cross-fertilize, breaking down artificial oppositions between reason and imagination, analysis and creation, work and play, individual and collectivity. We’ve let Mina Loy’s example teach us how to be innovative and experimental in digital humanities.

From the perspective of dominant culture, many of Mina Loy’s artworks and inventions “failed,” in the sense of being unpublished, never produced, overlooked, or lost. They failed because, committed to experiment, Loy ventured outside norms, conventions, and proven strategies that would guarantee success. Yet she succeeded in creating compositions that continue to fascinate, provoke, and delight a century later. Loy declared that

the aim of the artist is to miss the absolute—the only possible creative gesture.5

With similar spirit, we might say that the aim of the feminist DH theorist is to miss the absolute—to fail to produce a total, complete theory may be the only possible creative gesture worthy of the en dehors garde.

- Majorie Perloff, “Collage and Poetry,” https://marjorieperloff.com/essays/collage-poetry/ Accessed 9 March 2019.

- James Martin Harding,Cutting Performances : Collage Events, Feminist Artists, and the American Avant-Garde, p.24, 1st pbk. ed., 1st pbk. ed., University of Michigan Press, 2012, Project Muse, Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

- Sophie Seita,“The Politics of the Forum in Feminist Avant-Garde Magazines,” Journal of Modern Literature, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Fall 2018), 176.

- Stephen Ross, Hypothesis annotation, 5 April 2o15

- Loy. “Conversion.” Stories and Essays of Mina Loy, p.228, Edited by Sara Crangle. Dalkey Archive Press, 2011. 228.