Mina Loy, the artist at the heart of this born-digital scholarly inquiry, was an inveterate visionary, ever seeking new and better designs in art and life. In her 1917 poem “Songs to Joannes,” for example, she pauses in the middle of a biting satire of a failed love affair to envision more fulfilling possibilities:

We might have lived together

In the lights of the Arno

Or gone apple stealing under the sea

Or played

Hide and seek in love and cob-webs

And a lullaby on a tin-panAnd talked till their were no more tongues

To talk with

And never have known any better (LLB96 59)

The lovers in “Songs to Joannes” never fulfill the speaker’s ardent hopes: egos and inhibitions drive them apart. Yet though her speaker fails in her romantic quest, Loy exuberantly succeeded in her literary quest to transcend limitations of gender and genre. Undaunted by literary, social, or moral constraints, Loy defies feminine propriety and breaks with poetic convention, writing about sex, eliminating punctuation, and splitting syntax to tell a new kind of love story—perhaps imagining that future readers, emboldened by her poem, will not to be so constrained.

Today, a century later, inspired by Loy’s visions of new possibilities for human relationships, we wonder:

- How might we bring pleasure, play, and more “tongues/to talk with” into the work of scholarship?

- How might we break out of the conventions of scholarly publication in order to design new forms of communication with you, our readers?

- How might digital tools alter our scholarly methods and processes, allowing us to work together rather than in isolation or competition?

- How might digital platforms transform the print forms we traditionally use to share our research with others?

Mina Loy: Navigating the Avant-Garde explores these questions, seeking new and better designs for scholarship in the age of digital production. Our scholarly Baedeker, or travel guide, aims to help users navigate Mina Loy’s relationship to the avant-garde, including texts, artwork, and artifacts related to Mina Loy and her circles. In doing so, we aim to provide what Whitney Trettien describes as “more textured histories of women’s writing and work.”1

In terms of its impact on the production and dissemination of knowledge, the transition from print to digital publication is as revolutionary as the shift from manual to mechanical reproduction, which German Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin theorized nearly a century ago. Our subtitle, “The Work of Scholarship in the Age of Digital Production,” plays on the title of Benjamin’s famous 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In that essay, Benjamin analyzes how mechanical advances in print technology have transformed art and culture, beginning with a simple history lesson:

In principle a work of art has always been reproducible. Man-made artifacts could always be imitated by men. Replicas were made by pupils in practice of their craft, by masters for diffusing their works, and, finally, by third parties in the pursuit of gain. Mechanical reproduction of a work of art, however, represents something new.2

Today in the age of digital production, we face a similarly momentous transformation, one with significant implications for scholarship. Revising Benjamin’s words for our digital age, we might begin:

In principle a work of scholarship has always been reproducible. Scholarly monographs could always be imitated. Reprints were issued for students in practice of their discipline, by masters for diffusing their works, and, finally, by third parties in the pursuit of gain. Digital production of a work of scholarship, however, represents something new.

The “born-digital” work of scholarship cannot simply reproduce print books in electronic formats; it must transform scholarly processes and products. A complete redesign is in order.

From Print Books to Digital Publication

Consider how the tectonic shift from print culture to the digital age is transforming practices of reading and writing, turning a solitary, contemplative endeavor into an interactive, multimedia activity. The shift is also affecting scholarly practices, albeit more gradually. Humanities professors, rooted as we are in print-based traditions and methodologies, tend to approach the digital revolution with attitudes ranging from healthy skepticism to horror. The popular “blog,” for example, seems the antithesis of the thoroughly researched, well-reasoned, expertly vetted analysis that we expect in academia.

As Scott Pound explains in “The Future of the Scholarly Journal,” our expectations arise from a system for producing and disseminating scholarly knowledge that dates back to the seventeenth century.3 Working within this system today, a lone scholar typically researches and writes an academic monograph that takes years to prepare and requires the private approval of two anonymous experts in the field before being published by a prestigious university press, issued in an expensive hard copy , purchased primarily by academic libraries, and reviewed in subscription based, peer-reviewed academic journals read only by professionals in the field.

Whereas the print model of scholarly production puts on premium on the values of individuality, permanence, hierarchy, linear thinking, scarcity, and depth, the digital age ushers in new systems for producing and disseminating knowledge, as well as alternative practices and values such as collective intelligence; networks; divergent, lateral, systemic thinking; abundance; and breadth (Pound). Today, anyone with access to a computer can publish a blog; research questions can be crowdsourced on bulletin board systems such as Reddit; and the general public can contribute to the expansion and regulation of free, open-access informational resources like Wikipedia, where you can learn about any subject in minutes, click on numerous links, and surf the World Wide Web to related (and unrelated) sites.

Whereas the print model of scholarly production puts on premium on the values of individuality, permanence, hierarchy, linear thinking, scarcity, and depth, the digital age ushers in new systems for producing and disseminating knowledge, as well as alternative practices and values such as collective intelligence; networks; divergent, lateral, systemic thinking; abundance; and breadth (Pound). Today, anyone with access to a computer can publish a blog; research questions can be crowdsourced on bulletin board systems such as Reddit; and the general public can contribute to the expansion and regulation of free, open-access informational resources like Wikipedia, where you can learn about any subject in minutes, click on numerous links, and surf the World Wide Web to related (and unrelated) sites.

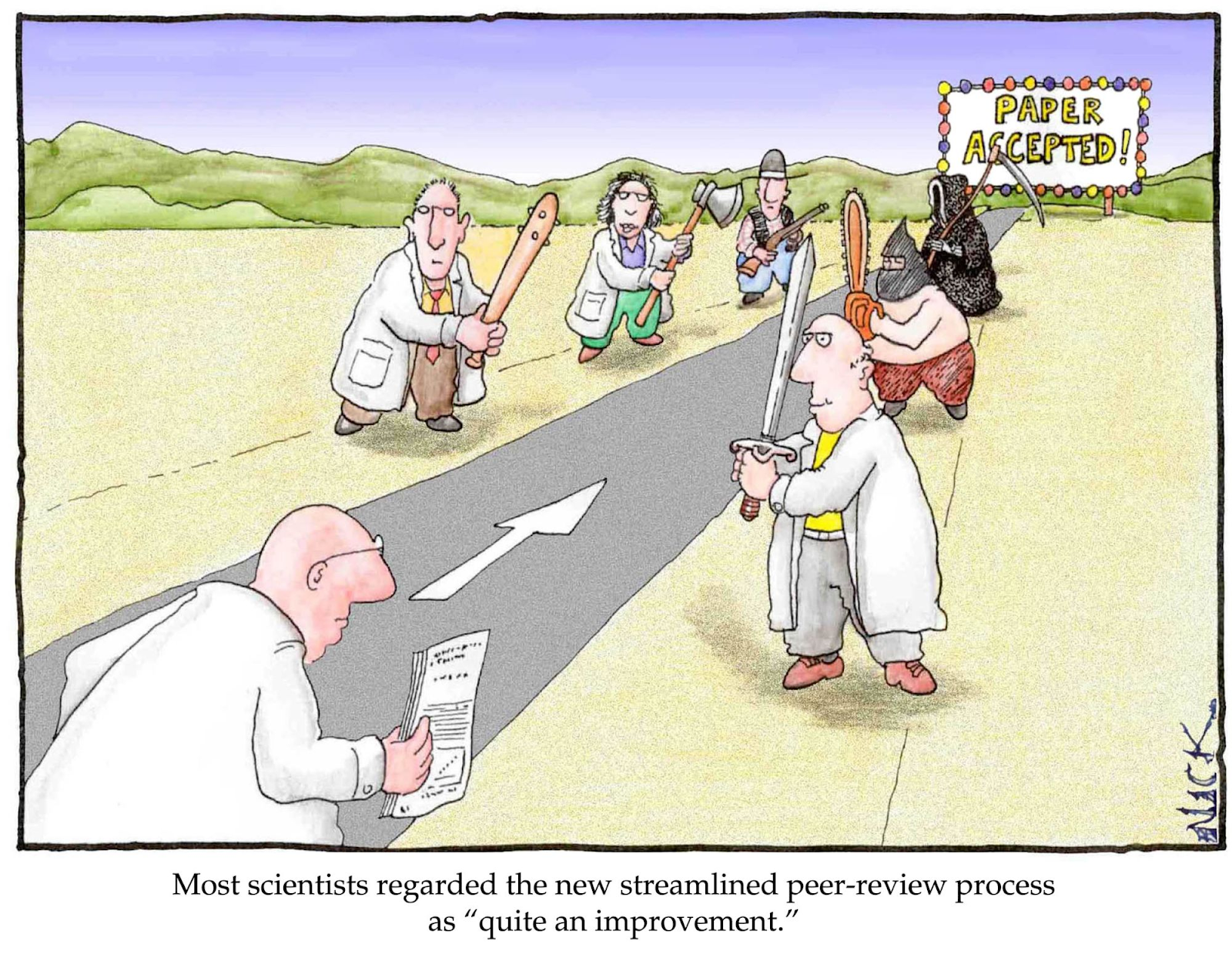

The typical scholarly response has been to resist the resulting tide of information abundance, as Pound explains: “For the most part, the scholarly community has managed to artificially maintain its traditional grounding in information scarcity through hefty subscription rates, low acceptance rates, and slow mechanisms for vetting research.” Innovation in scholarly vetting procedures can a slow, arduous, and painful process, as Nick D. Kim’s cartoon shows.

But not all scholars resist the change. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, co-founder of the digital scholarly network MediaCommons is a leader in the effort to adapt digital tools and platforms to serve the highest standards of scholarly inquiry and communication. “The blog is not a form but a platform,” she argues, explaining that the blog is not a genre that precludes sustained analysis or concentrated attention, but a “stage on which material of many different varieties—different lengths, different time signatures, different modes of mediation—might be performed.”4 Fitzpatrick and other digital humanities (DH) pioneers have begun to utilize digital platforms for academic writing, with promising results. For example:

- Fitzpatrick used MediaCommons to write, receive peer review, and revise Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy, which was simultaneously published as a print book by NYU Press.

- Whitney Trettien’s Master’s thesis, “Computers, Cut-ups, & Combinatory Volvelles” generates scholarly arguments and theory in nonlinear, participatory frameworks, while her co-edited digital journal Thresholds uses split-screen architecture to embody the entanglement of texts and ideas that is the essence of critical reading and writing.

- Lauren Klein’s forthcoming Data by Design: A Cultural History of Data Visualization, 1786-1900 pairs a monograph with an interactive digital companion, tracing modern data visualization techniques back to Enlightenment models and arguments “about how knowledge is produced, and who is authorized to produce it.”

These innovators recognize that in the scholarly enterprise, as in book publishing, we must avoid simply relocating print-based practices to the digital realm. In this regard, we can take lessons from non-academics like independent writer, designer, and publisher Craig Mod:

Everyone asks, ‘How do we change books to read them digitally?’

But the more interesting question is, ‘How does digital change books?’5

Academics may be similarly inclined to wonder, “How do we change our scholarship to publish it digitally?” But the more interesting question is: ‘”How does digital change scholarship?”

Rather than simply uploading our articles as PDFs, we must put our minds and imaginations to the task of designing new methods and forms of digital scholarship—forms capable of presenting long and deep inquiry, fostering intellectual exchange, and maintaining rigorous standards of peer review.

Digital Design

Design is fundamental to the work of scholarship in an age of digital production. Just as books need readers, digital tools and media need users. But digital resources must pay more attention to design as a mediating element of reading. Every literate reader knows how to read a book, but the conventions for reading online are still forming and changing as more sophisticated digital tools enable new modes of presentation and communication. Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp explain:

Printed books and humanistic scholarship have a shared history. For centuries, humanists have worked with formats—the printed page, the bound codex—that have remained essentially consistent. But communication in digital environments has required the invention of new forms, tools, and schemata. The lack of conventions and the opportunity to imagine formats with very different affordances than print have not only brought about recognition of the socio-cultural construction and cognitive implications of standard print formats, but have also highlighted the role of design in communication. Modeling knowledge in digital environments requires the perspectives of humanists, designers, and technologists.6

By collaborating and combining our areas of expertise, we can design new and flexible conventions for immersive, online reading.

Multimedia journalism such as John Branch’s Snow Fall (NYTimes.com) and David Boeri’s Bulger on Trial (WBUR.com) provided inspiration for our project, demonstrating that online reading of long-form narratives is not only possible but potentially more engaging than print—when sufficient attention is given to design. These projects integrate interactive maps, documents, and media into non-fiction narratives, guiding readers through complex, information-rich territory.

Attention: Style

To capture and hold readers’ attention in an era of information abundance, Richard Lanham argues, we must focus on style:

The devices that regulate attention are stylistic devices. Attracting attention is what style is all about. If attention is now at the center of the economy rather than stuff, then so is style. It moves from the periphery to the center. Style and substance trade places.7

Academics are unlikely to accept such a tradeoff of substance for style, however, and for good reason: accuracy of data and quality of interpretation remain paramount in scholarship, so much so that stylish delivery may be viewed with suspicion. “Traditionally, academic writing has derived much of its authority from its explicitly anti-rhetorical stance, its relative indifference to audience, and its refusal of style,” Pound argues, insisting that “such a model can only exist in the context of information scarcity.” In this era of information abundance, scholars can no longer afford to be indifferent to audiences or to neglect style. But rather than subordinating substance to style, as Lanham argues, we must wed style and substance and focus our attention on matters of design.

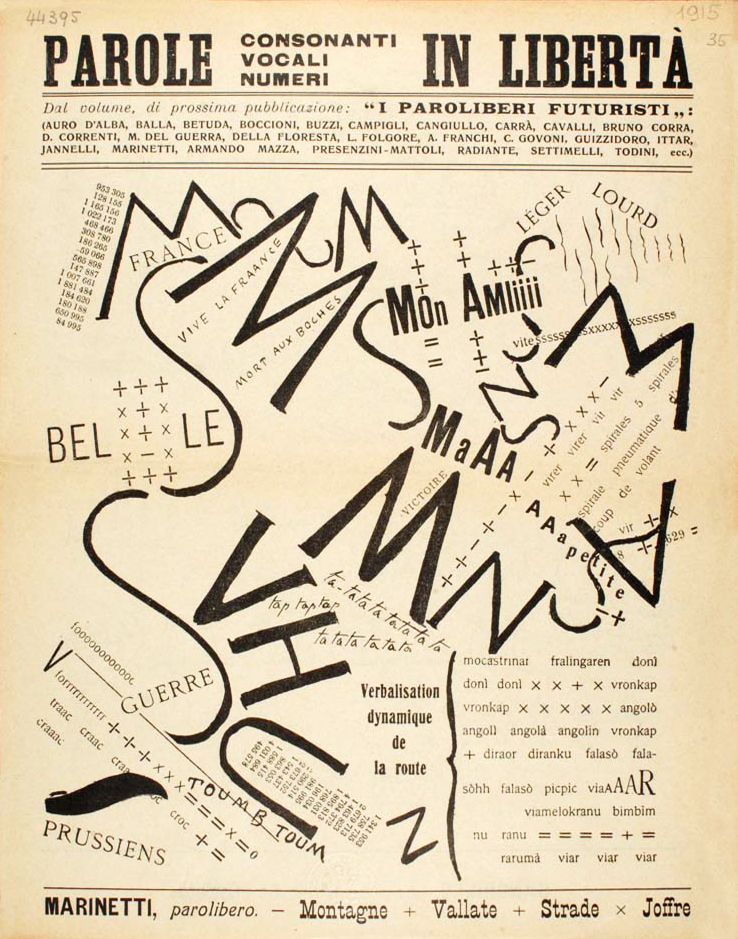

At the beginning of the twentieth-century, avant-garde artists and writers experimented with form in an effort to disrupt habits of seeing and reading. This 1915 Italian Futurist poster by F.T. Marinetti, for example, employs “Parole in Liberta” (“words in freedom”), demanding that readers participate in assembling the collage of signs and symbols into sounds and meaning.

Just as the historical avant-garde deployed aesthetic design to disrupt conventional habits of reading and seeing, scholars today must use UX (user experience) design to defy habits of both print-based reading and web surfing. We must design immersive online environments that can sustain the reading of complex verbal-visual texts and long-form scholarly narratives.

Definition: UX design

The process of enhancing user satisfaction by improving the usability, accessibility, and pleasure provided in the interaction between the user and the resource.

Creators of online content must use UX design to attract, orient, and reward users with a satisfying, even pleasurable reading experience, so that navigating an online resource can be as intuitive, immersive, and pleasurable as reading a good book. Good UX design helps users navigate digital spaces with ease and confidence, so that design itself operates as a Baedeker or travel guide.

As Burdick et al argue, if the humanities are to thrive in the age of digital production, then design must move to the forefront of our scholarship:

When print artifacts are no longer the primary medium for knowledge production in the humanities, norms begin to change and the ‘how’ of design reasserts itself at the core of every ‘what.’ In embracing such a transformation, the Digital Humanities not only takes on a new set of disciplinary and technological tasks, but also a world of linked and lived experiences that are at once social and epistemological in character. (Burdick et al 76).

Scholars, like their readers, must learn to read and write in more interactive and social ways—ways that will transform what we see, how we learn, and what we know.

- Whitney Trettien, COMPUTERS, CUT-UPS AND COMBINATORY VOLVELLES, https://www.whitneyannetrettien.com/thesis/#thesis, Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in an the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), Marxist Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm

- Scott Pound, “The Future of the Scholarly Journal,” Amodern 1, February 2013, https://amodern.net/article/the-future-of-the-scholarly-journal/

- Kathleen Fitzpatrick, “Reading (and Writing) Online, Rather Than on the Decline,” Profession, 2012, p. 48, www.jstor.org/stable/41714136.

- Craig Mod, “Post-Artifact Books and Publishing,” 2. https://craigmod.com/journal/post_artifact/.

- Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp, Digital-Humanities. MIT Press, 2012, p. 10.

- Richard Lanham, Economics of Attention, University of Chicago Press, 2007, pp. xi-xii.