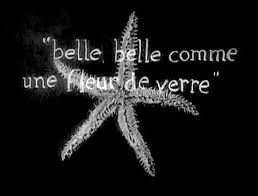

Surrealism originated as a poetic movement, and one of its enduring legacies was to expand the understanding of “poetry.” Breton called the activity of revealing the commingling of surreality and reality “poetry,” and thus the poetic act was as central to film, photography, and painting as it was to poems proper. Juxtapositions created by uses of different media (word and image) and by collaborations between different artists became a key “poetic” technique in Surrealist works meant to bring together two distinct states, dream and reality, the unconscious and conscious mind. Thus Breton’s understanding of poetry as a means of realizing a surreality, whether through visual or verbal media, led to verbal-visual hybrids (collaborative books, film-poems) and to collaborations between artists and writers.

Surrealism marks an important turn in the long history of word/image relations, understood by most scholars of ekphrasis (defined by James Heffernan as a “verbal representation of a visual representation”) as an antagonistic struggle, historically gendered in terms of a silent, feminined image or artwork narrated or made to speak by a male writer (Museum of Words 3, 7).1 Even as recent scholarship on feminist and queer ekphrasis has complicated this understanding of word-image relations, it has often come up short in addressing (or has avoided altogether) the works of the avant-garde.2 Surrealist poets and artists tended to collaborate and to work across verbal/visual boundaries, just as they challenged other oppositions assumed to be antagonistic (e.g. dream and reality).

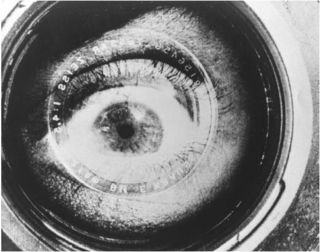

Many of Loy’s poems from the 1920s and 30s participate in and transform the tradition of ekphrasis, opening up the kinds of media that poems and other texts represent, and using the relationship between word and image to advance feminist commentary on how gender and sexuality shape technologies of vision, the gaze, eros, and imagination. Loy’s work in diverse genres and media invites us to complicate the conventional word/image antagonism of ekphrasis.3

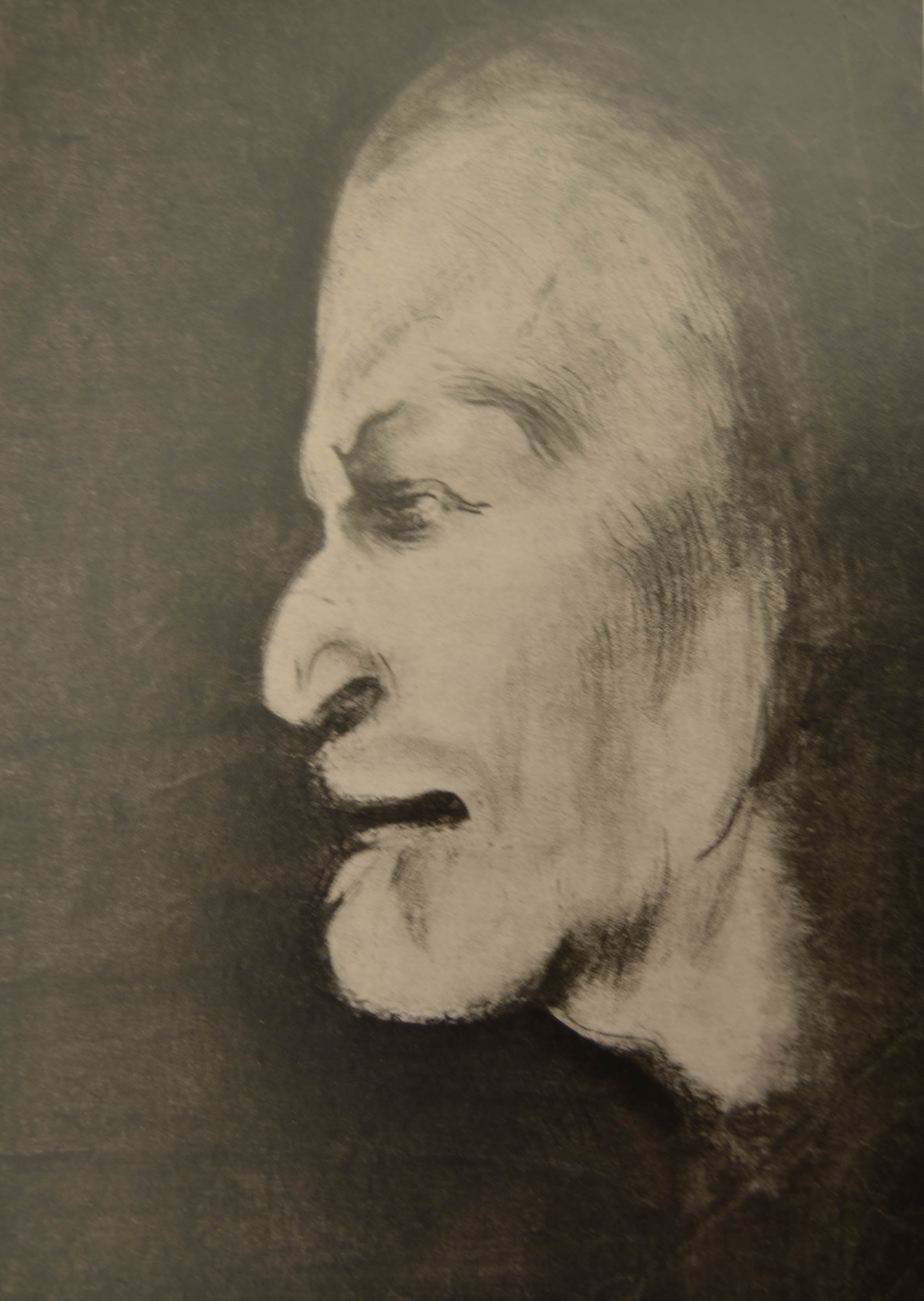

Notably Mina Loy began her career as a painter, not as a poet: she attended art school in London and Munich and exhibited paintings in the Salon d’Automne in 1906, London’s Carfax Gallery in 1912, the Futurist Exhibition in Rome in 1914, and the Independent Artists Exhibition in New York in 1917. She published her first poems in 1914, and from that point onwards continued both to write and to create visual art.

Loy responded to the possibilities and limitations of word and image as an artist capable of working adeptly with both, and like the Surrealists she was interested in expanding an understanding of the “poetic” and in experimenting with new, hybrid genres. Loy has affinities with the Baroness Elsa von Freitag Loringhoven, Wyndham Lewis, Duchamp, and Cocteau as artists who worked in and across many genres and kinds of media: for these artist-poets, language remained important in the composition of visual works, and vice versa.4 Just as Loy’s poems from the Paris years and post-1936 New York years often comment upon visual art and desgin, Loy’s visual art created during her Paris years is often poetic, and the reviews of her 1933 exhibition at the Levy Gallery compared her painting to that of Blake, Apollinaire, Eluard and Cocteau, all of whom were interested in the poem-painting (Burke 379). Not coincidentally, while Loy’s paintings were shown at Levy’s Gallery in 1933, one of Loy’s paintings titled “Faces” was simultaneously shown at the Hartford Atheneum in their “Exhibition of Literature & Poetry in Painting Since 1850.”5

If we consider Loy’s poetry alongside her lamps and paintings, her novel Insel, her autobiographical fiction, and her published as well as unpublished essays and stories, the Paris years 1921-1936 are notable for Loy’s experimentation with and across verbal and visual media, consistent with Surrealist poetics.

Leaving behind the conventional antagonism between word and image for an erotics of word and image, many Surrealist poets and artists used the crossing and mixing of media to dramatize the play of difference and affinity, competition and union, that animates desire. In his discussion of Lautreamont’s celebrated proto-Surrealist image of “the chance meeting upon a dissecting table of a sewing-machine with an umbrella,” Ernst stated that “umbrella and sewing-machine will make love” (This Quarter 81).

Not only did Ernst and other male Surrealists emphasize the erotics of bringing together disparate realities through the surrealist image, and through the related practices of collage and frottage, but collaborations involving different artists and media contributed to the erotic dynamic of these surrealist works. Collaboration facilitated the “fortuitous encounter upon a non-suitable plane of two mutually distant realities” (Ernst) that centered the Surrealist image and practices of collage and frottage. Breton argued in his Surrealist Manifesto that “the forms of Surrealist language adapt themselves best to dialogue. Here, two thoughts confront each other” (Manifestoes 34), and he described Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields), his collaboration with Philippe Soupault, as “the first purely Surrealist work,” a “dialogue…freeing both interlocutors from any obligations of politeness” (Manifestoes 35).

Similarly, Ernst in Beyond Painting argued, “When the thoughts of two or more authors were systematically fused into a single work (otherwise called collaboration) this fusion could be considered as akin to collage” (quoted in Lydenberg 279). 6

This conception of the erotics of word-image relations, collage, and collaboration was gendered. As Linda Kinnahan argues, Lautreamont’s sewing machine became a privileged icon in the visual art of Dali, Man Ray, and Cornell, with women’s bodies the materials that are pierced, produced, and/or sewn by the machine, reflecting the gendering of the labor of sewing, of the consumer, and of fashion itself, a complex that Mina Loy would critically engage in “Mass-Production on 14th Street” (Kinnahan, Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography 93-4). Insofar as the icon of the sewing machine self-reflexively figures the creation of collage through the “sewing together” of disparate materials, Loy’s work as a seamstress and dress designer conjoined with her critical engagement with Surrealism would prove important to her development of a different understanding of collage and the Surrealist image. Through her friendship with and artistic dialogue with Joseph Cornell, Loy would articulate these differences.

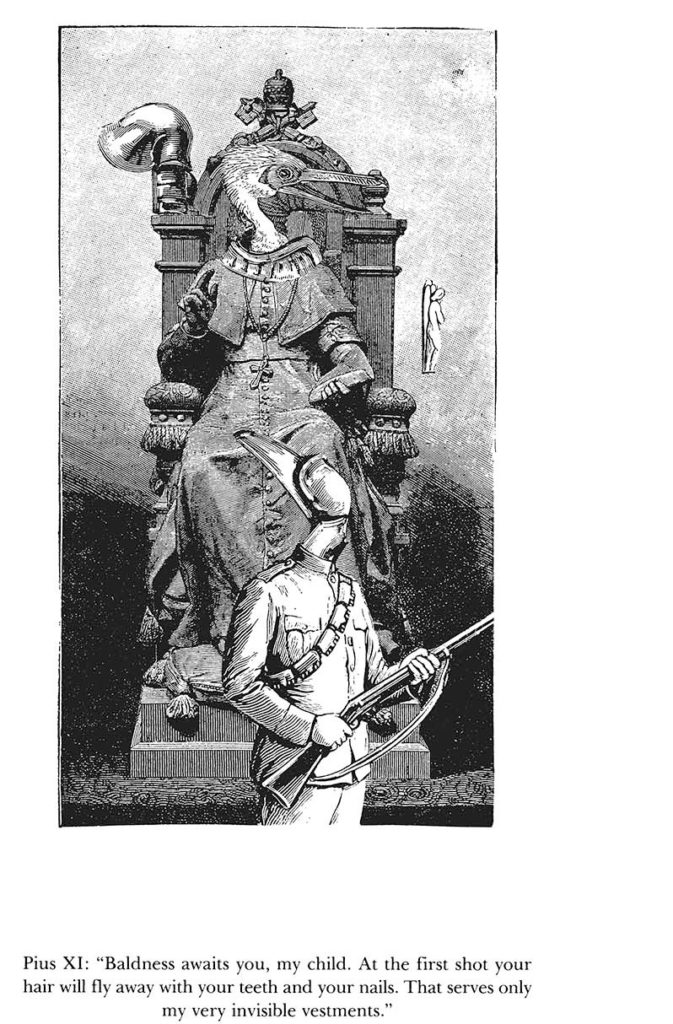

Loy’s verbal works that engage Cornell’s art blur the line between ekphrasis and collaboration, in that they form part of an ongoing artistic dialogue, involving a degree of reciprocity (see “Sidewalk Surrealism”). Moreover, as Jessica Burstein has argued, Loy often used one form of her art to comment on her designs created in a different medium (Cold Modernism 190). Burstein draws attention to the relationships Loy explored across media; for instance, she emphasizes the echoes between Loy’s lamp designs and her lampshade-like hats and dress designs (190). In the 1920s and 30s, Loy would explore ideas about human-animal hybridity in her poems, novels, paintings, and objects. Similarly, Loy’s Bowery poems and collages from the 1940s and early 1950s are intimately connected, suggesting a collaboration across media (see “Collecting Mina Loy”). Loy’s oeuvre suggests that “ekphrasis”and “collaboration” are concepts that need to be expanded to encompass an artist who often alluded to, described, and collaborated with her own artwork in a different medium. Intermediality may prove to be a more productive concept to engage the relationship between Loy’s artwork in different media.

Many women artists and poets were inspired by the Surrealist emphasis on collaboration.7 Renée Hubert points out that in Surrealist circles, while men collaborated with other men, and women occasionally collaborated with other women, the most common collaborative grouping was the heterosexual couple; collaborative works created by gay or lesbian couples were less common (1, 6). The works of Claude Cahun (born Lucy Schwob) and her partner Marcel Moore (born Suzanne Malherbe) were groundbreaking in this respect. The Surrealist painters Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington were also friends and artistic collaborators, and their collaborations suggest different models of aesthetic affiliation than those commonly associated with the male Surrealists (Arcq, Moore, Van Raay, Surreal Friends).

Collaborative works involving women not only commented on and refigured notions of original authorship, but also explored and challenged social relationships defined by gender, sex, race, class, and power (Hubert 4, 10, 27). In visual-verbal collaborations, patriarchy and its associated hierarchies, including the conventional antagonism between a masculinized word and feminized image, were challenged and opened up: collaboration often served as a means of exploring new configurations of gender and desire, beyond the limits imposed by Breton and the Surrealist movement.

- On this word/image antagonism see W.J.T. Mitchell, James Heffernan, Elizabeth Bergmann Loizeaux, Ellen Levy.

- Scholarship on feminist and queer ekphrasis has illuminated and complicated the gendering of word-image relations, revising the conventional notion of a male poet-viewer who seeks to control or possess a feminized silent image or art object by narrating it or making it speak. On ekphrasis and modernist women’s poetry see also Lundquist, Blau du Plessis, Bergmann-Loizeaux, and the essays on women’s ekphrastic poems in Halpern, Hedley and Spiegelman, Eds. On queer ekphrasis see in particular Brian Glavey.

- On Loy and ekphrasis see Ashley Lazevnick and Linda Kinnahan.

- Loy’s career was similar to that of the Baroness: “Whether working on assemblage art, poetry, criticism, or performance, the Baroness always pushed her work to the extreme edges of genres, creating hybrid genres. With the everyday as her chosen site for revolutionary artistic experimentation, she imported life into art, and art into life, thus taking modernity out of the archives, museum spaces, and elite literature to anchor it in daily practice” (Gammel, Baroness 10).

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, Box 6, Folder “Exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery 1933, photographs and reviews.”

- On the origins of surrealist collage Elsa Adamowicz notes, “In the pictorial field the surrealist model is provided by cubist papiers collés, while in the literary field Tzara’s ‘pour faire un poème dadaiste’ is the founding recipe … ” (15).Ernst noted that while collage techniques “were being used before our advent, surrealism has … systematized and modified them … ” (This Quarter 80). Lydenberg argues that “collage’s erotic potential is most explicitly developed in Dada and Surrealism: the process of collage experimentation, both verbal and visual, may be seen as an erotic encounter and its fertile outcome,” and notes that many Surrealist artists and writers who employ collage “describe the interaction of elements in their work in terms of desire, copulation, and regeneration” (272).

- Women poets’ and artists’ collaborative works have received less attention than ekphrastic poetry, but Lundquist in her study of Barbara Guest’s collaborations with Grace Hartigan and Mary Abbott suggests that collaboration provided mutual recognition and support, while Kinnahan’s study of Erica Hunt and Alison Saar’s Arcade explores how their collaboration offered an opportunity to reflect on, denaturalize, and critically transform the visual economies shaping inherited understandings of the racialized body (see in particular 80-109). On the homo-erotic nature of collaboration, see Koestenbaum, Smith.