Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables (1958) & The Bodley Gallery Exhibition (1959)

‘You should have disappeared years ago’ —-

So disappear

on Third Avenue

to share the heedless incognito (LB96 109)

The statement that opens Loy’s poem “On Third Avenue” — “You should have disappeared years ago” — may have embodied a damning voice directed at the poet and the homeless, but also articulates the poet’s defiant challenge to make a new kind of poetic art out of this disappearance (see “Return to New York”). For Loy, to “disappear” signaled a loss of power but also permitted an artistic freedom to experiment without care for the world’s judgment, enabling her unique perspective on the Bowery. Disappearance — at once imposed by age and circumstance, but also embraced through personal inclination and artistic sensibility – resonated with Mina Loy’s career-long negotiation of the margins and with the process of publishing and exhibiting her art.

As this scholarly guide navigates Loy’s career and relationship to the avant-garde in Florence, Paris, and New York, Loy’s ambivalence about and tenuous relation to public channels of recognition, particularly during her later years in New York (1937-1953), come into sharper focus. Her “en dehors garde” position on the margins of largely male avant-garde movements (which were already marginal in the wider culture) required that she negotiate gendered forces in the art world and literary publishing from a place of little power. This necessitated a complex dance to get her work to the public: as discussed below, in New York Loy relied on the help or collaboration of male friends, editors, publishers, and gallery directors, even as her work was deeply individual, critical of organized art institutions, and scornful of male privilege.

Although Loy privately felt certain of her poetic and artistic gifts1, her penchant for the margins of modernist and avant-garde circles presented obstacles to publishing her writing, exhibiting her art, and finding backers to help produce her commercial designs. Peggy Guggenheim was an important patron and facilitator of the sale of Loy’s “Jaded Blossoms” objects and of her lamps in the 1920s, but lacking such a patron in New York, most of Loy’s designs and patents from the New York years did not result in commercial products (see “Surrealist Objects”). As discussed in the Paris Surrealism chapter, Loy’s publications and exhibitions from her second stay in Paris (1923-1936) represent only a fraction of her artistic output during these years, and this remained true for her years in New York (1937-1953).2

Loy’s editors and biographers (chiefly Marisa Januzzi, Carolyn Burke, Roger Conover, and Sara Crangle) in their careful tracing of Loy’s career, including the history of her exhibitions, publications, and critical reception, have demonstrated that Loy’s connection to particular circles (the Others group, the New York Dada circle, the Little Review circle, Natalie Barney’s salon, the Julien Levy Gallery) was her bridge to the public: Loy depended on friends in these circles to help place her writing and arrange showings of her visual art.3 Roger Conover points out that at the start of Loy’s career in Florence, Mabel Dodge and Carl Van Vechten placed Loy’s poetry in the little magazines, while in later years, Djuna Barnes, Peggy Guggenheim, and Julien Levy assumed this “agent’s function” (LB82 xxx).

Cristanne Miller has suggested that “Loy’s passivity about her later publishing may be a sign of her general lack of perceived agency in the infrastructures of modernism” (Cultures 180). Similarly, Sara Crangle argues that

as ‘modernism’ became an aesthetic construct, Loy did not become part of its canon, a fate she shared with many of her female peers. […] As explanations for her waning popularity, critics point to Loy’s reclusiveness, as well as her disinterest in self-promotion and publishing in later years. However, it should be borne in mind that Loy was only ever well-known within avant-garde circles, and even there, she often remained on the periphery. (“Introduction” SE ix)

Both Cristanne Miller and Sara Crangle emphasize that Loy’s position on the periphery affected her ability to publicize her work, and suggest that in New York her relation to the avant-garde had become more marginal. Although Loy’s desire to publish and exhibit her late work hadn’t diminished, her efforts to secure publications and a gallery exhibition were often unsuccessful, and her letters (discussed below) record her frustration.4 In New York Mina Loy was no longer tied directly to a particular little magazine or artistic circle that could help her navigate a route to the public, and her key relationship, to Julien Levy and his gallery, although more tenuous than in Paris, proved to be critical at this juncture.

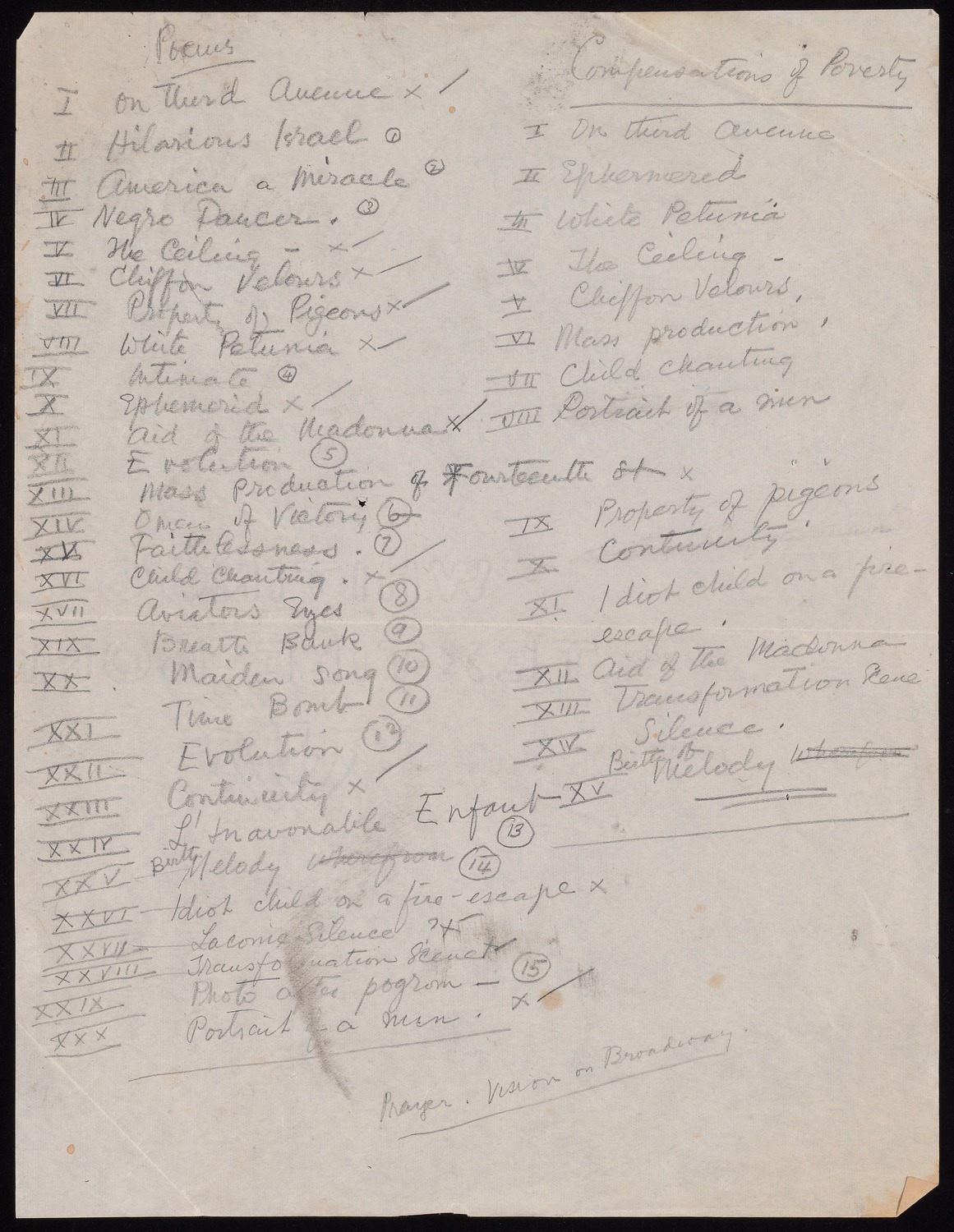

Despite the barriers she confronted, Loy persisted and ultimately succeeded in her efforts to publish and exhibit her work. Roger Conover and others have noted that Loy grouped her late poems under the title “Compensations of Poverty” and “probably hoped to publish them as a book” (LB96 207).5 A handwritten list of poems by Loy (see image below) titled “Compensations of Poverty” appears to be culled from a longer list of unpublished “Poems” on the same page, indicating a coherent design.

In the 1940s and 1950s Loy was in frequent contact with Julien Levy, pressing him to arrange an exhibition for her Bowery Constructions; Levy continued to help Loy place her poetry and to mediate her connection to publishers and art galleries.6 Levy was responsible for Loy’s first solo exhibition at his gallery in 1933, and with the help of Duchamp, arranged her second exhibition at David Mann’s Bodley Gallery in 1959.

As Loy depended on friends to help publish and exhibit her work, she was fortunate that old and new friends in New York recognized the value of her Bowery poems and constructions. In addition to Julien Levy, a handful of Loy’s old friends — Djuna Barnes, Berenice Abbott, Joseph Cornell, and Marcel Duchamp — stepped in to help, as did a younger generation of writers, editors, and gallery directors including Kenneth Rexroth, Gilbert Neiman, Henry Miller, Jonathan Williams, and David Mann: together they championed Loy’s work and demonstrated its continuing relevance to the avant-garde.

The intersecting efforts of these older friends and more recent admirers resulted in two related events in the late 1950s that brought Loy’s poetry and visual art to broader public prominence, and helped to ensure that her work would reach later generations. I briefly recount the history of these two events to suggest how Loy’s navigation of the avant-garde affected the re-appearance of her work in the late 1950s.

Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables (1958)

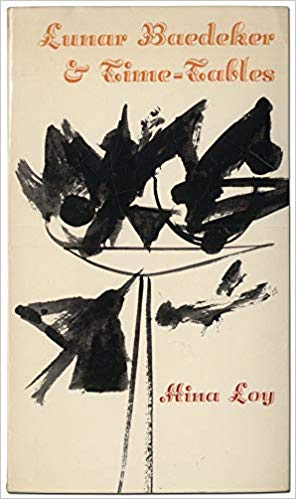

In 1958, thirty-five years after the publication of Mina Loy’s first collection of poems, Lunar Baedecker, Jonathan Williams brought out a second edition of Loy’s poems, titled Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables, through his Jargon Press located in Highlands, North Carolina. A poet, photographer, and graphic artist associated with Black Mountain College, Williams founded his press in 1952 and published experimental poetry, fiction, photography and art. He learned about Mina Loy’s poetry through his friend Kenneth Rexroth (Januzzi, “Bibliography” 553) and Rexroth’s publisher James Laughlin.

Like Jonathan Williams, Kenneth Rexroth was an important influence on the formation of a post-1945 American poetic avant-garde, what Donald Allen famously termed in 1960 the “New American Poetry.” Rexroth was a poet, painter, essayist, and Buddhist involved in the San Francisco Renaissance and early Beat movement, and like Mina Loy was committed to a career of poetic experiment. In 1944 Rexroth published “Les Lauriers Sont Coupés No. 2: Mina Loy” in Circle 1.4 (1944) 69-70. Rexroth made the case for the importance of Loy’s poetry and in doing so helped to bring it to the attention of a new generation of experimental poets: however, Loy was not included in Allen’s influential anthology, an exclusion that contributed to her marginalization in literary history.7 As Roger Conover points out, Rexroth concluded his essay “with a strong exhortation to his publisher at New Directions Press: ‘Mr. Laughlin, the ‘Five Young Poets’ are still Eliot, Stevens, Williams, Moore, Loy — get busy'” (LB96 214).

Rexroth was not alone in his efforts to spark interest in Loy’s poetry in the 1940s. In 1945 Gilbert Neiman, an artist, poet, and editor who (along with his wife Margaret) was friendly with Man Ray and Henry Miller in Los Angeles, met Loy for a dinner in New York arranged by Miller. After meeting Loy, Neiman facilitated the publication of four of her recent poems in Accent magazine: “Ephemerid” (1946), “Aid of the Madonna” (1947), “Chiffon Velours” (1947), and “Hilarious Israel” (1947)8

Roger Conover writes that “Neiman tried without success to place other poems for Mina Loy in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was turned down by Circle, Poetry, and several other magazines. He also tried to interest his own editor at Harcourt Brace in publishing a collection of her poems, possibly ‘Compensations of Poverty’, in 1947 (LB96 210). Neiman contacted Loy again in 1960 to invite her to publish some of her poems in his new magazine Between Worlds (LB96 210-211), which resulted in the publication of seven previously unpublished late poems.9

James Laughlin, the founder and publisher of New Directions Press and its associated annual anthology, likely read both Rexroth’s essay and Loy’s poems in Accent, for in 1948 he invited Loy to write a short review of W.C. Williams’ Paterson (which New Directions published serially in five books).10 In 1950 he published Loy’s long poem “Hot Cross Bum” in New Directions 12 (1950). Laughlin had been acquainted with Loy’s writing since at least 1938, when he began corresponding with her about publishing her surrealist novel Insel; after further correspondence and contact with Loy in the 1950s and early 1960s, Laughlin ultimately passed on publishing the novel.11 Although Laughlin chose not to publish Loy’s novel or a collection of her poetry, he did put Jonathan Williams in touch with Loy in 1957 (Burke 431).

Jonathan Williams traveled to meet Mina Loy in Aspen, Colorado, where she had been living under the care of her daughters Joella and Fabienne since 1953. With the family’s permission he prepared a collection of Loy’s poems, including selections from Lunar Baedecker (1923), sections from her long poem “Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose” (1925), and a selection of Loy’s late poems. The previously unpublished poems in the book include “Jules Pascin” written ca. 1930 in Paris (LB96 207), and from Loy’s later years in New York, “Omen of Victory,” “On Third Avenue: Part 2,” “Stravinski’s Flute,” “Transformation Scene,” and “The Song of the Nightingale is Like the Scent of Syringa.”12

Williams evidently felt the need to introduce Mina Loy’s poetry to a new generation of readers, given the time lapse between her first and second collections and the small number of poetry publications in the intervening decades. He prefaced Loy’s poems with an essay by W.C. Williams, an excerpt from Rexroth’s 1944 Circle essay, and an essay by Denise Levertov. The back cover contains further admiring commentary, with blurbs written by Henry Miller, Edward Dahlberg, Walter Lowenfels, Alfred Kreymborg, and Louis Zukofsky (See LBTT58, Januzzi “Bibliography” 525, Burke 432). Loy’s second book was ushered into print by a coterie of older and newer admirers, lead by Jonathan Williams.

The publication party for Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables was held at the Martha Jackson Gallery in December 1958. Carolyn Burke writes that Loy did not attend the party but telephoned from Aspen during the party (433). Absent in person but present through her voice mediated by telephone and by her book of poems, Loy’s presence-absence at this party was emblematic of her liminal place in literary history.13

A book party at an art gallery was appropriate for the poet-painter Mina Loy. While she had always worked across verbal-visual boundaries, her poems and assemblages inspired by the Bowery were particularly intertwined. As Roger Conover observes, “Some of these poems feature scenes, figures, and phrases also found in her three-dimensional assemblages” (LB96 209).14 Loy had created many of these works in tandem and envisioned the poems and assemblages exhibited together (see “Surrealist Poetics: Word and Image”); Carolyn Burke writes that Loy “scolded Jonathan Williams for not taking the trouble to hang her Bowery constructions at the gallery, where they belonged” (Burke 433).

Indeed, copies of Loy’s letters to Jonathan Williams in the Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller indicate that this oversight touched a nerve.15 While Loy’s letters convey her appreciation for Williams’ “book creation” and his concern for her poetry, in three letters Loy emphasizes her disappointment that Williams didn’t hang her pictures at the Martha Jackson Gallery for the book party. These letters imply that Loy understood her Bowery poems and Constructions as a coherent “poetic” collection in different media; they also reveal how highly Loy regarded her Constructions, and her longstanding, frustrated desire for an exhibition. In one letter she mentions that Duchamp had been working on an exhibition for her Constructions when she left New York, and adds, with self-deprecating humor that nevertheless reveals her sense of her achievement, “I will try to find someone to show you my ‘Bowery Masterpieces’ in New York if you would care to see them.”

In fact, letters exchanged in the mid-1950s between Julien Levy and Mina Loy indicate that Loy had been pressing Levy to help arrange an exhibition for her Constructions since she left New York in 1953, and that he had begun to contact galleries on her behalf in 1954.16 In a 1955 letter to Joseph Cornell, Loy writes that she has heard that Cornell didn’t appreciate her Constructions, suggesting that he had recently seen them.17 In addition to asking Julien Levy for his help, Loy spoke with Djuna Barnes and Berenice Abbott about her desire for an exhibition: in 1955 Barnes urged Loy to follow up on arranging a gallery show for her new works. At some point Berenice Abbott photographed Loy’s assemblages to help her try to secure a gallery exhibition.18 While Loy’s friends had already initiated the effort to exhibit Loy’s Constructions, the publication of Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables in 1958 spurred Levy and Duchamp to action, resulting in the 1959 Bodley Gallery exhibition.

The Bodley Gallery Exhibition, 1959

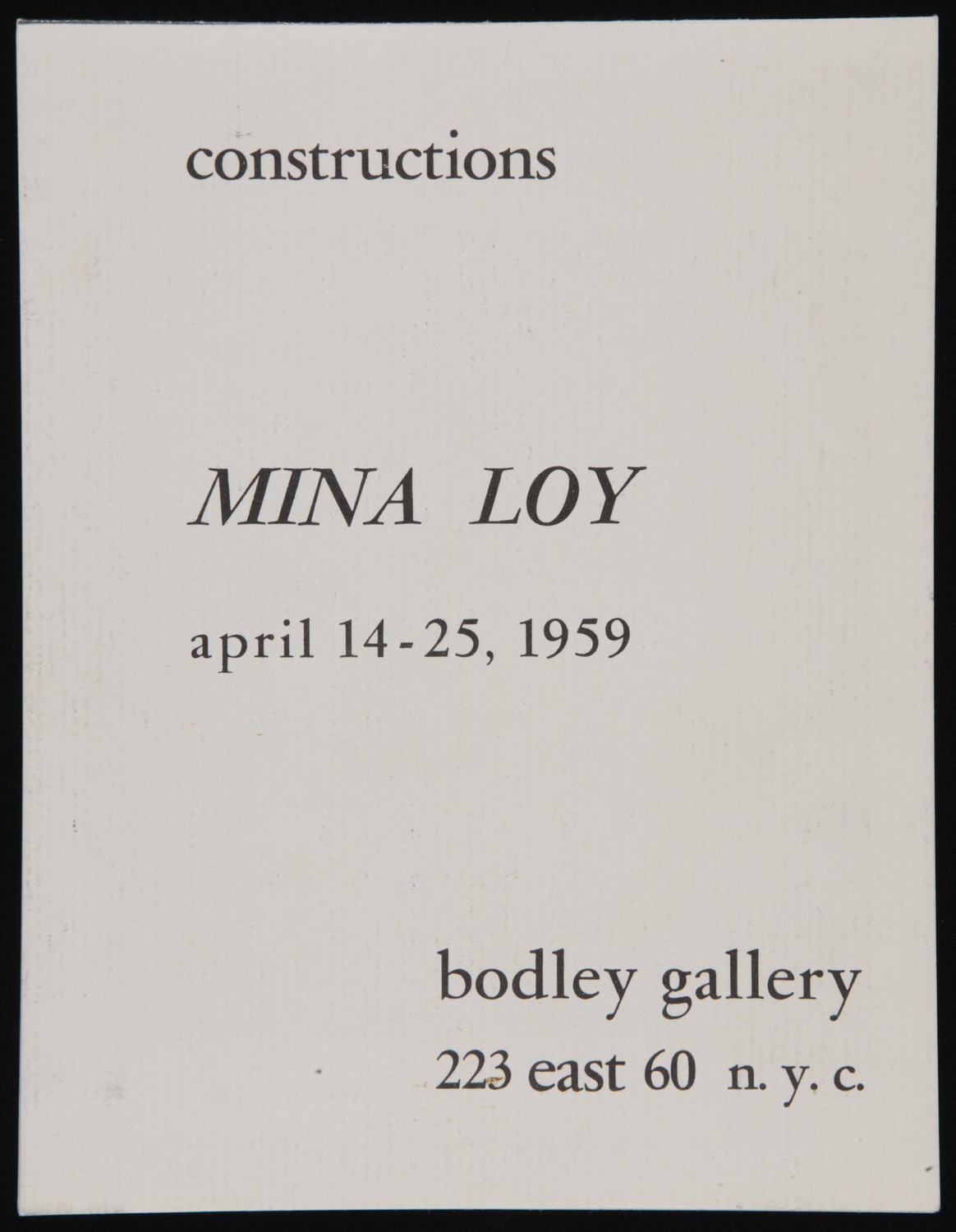

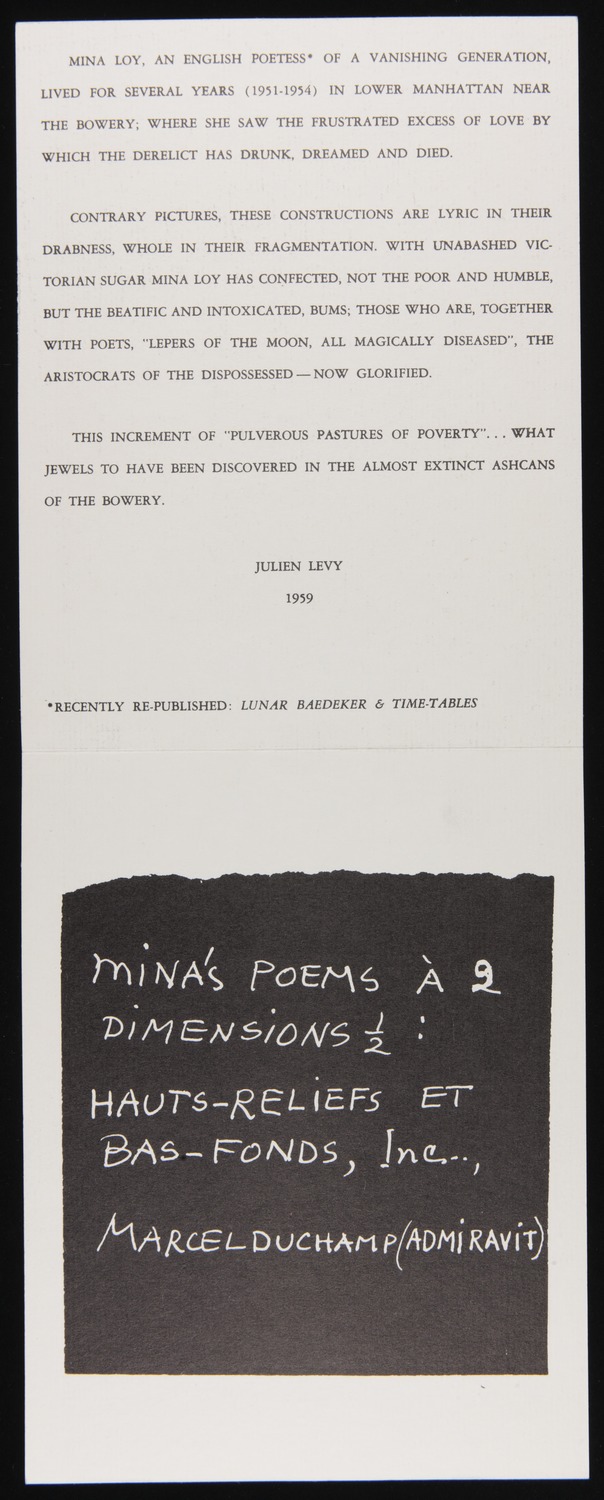

Loy’s keen desire for an exhibition of her Bowery assemblages would come to pass: her Constructions were shown at David Mann’s Bodley Gallery, 223 East 60th Street, on April 14-25, 1959.

When Mina Loy moved to Aspen in 1953, her Constructions were wrapped in plastic and stored in her apartment at 5 Stanton Street, under the care of her housemates Alex Blossom and Steve Ferris (Burke 433; see also Carolyn Burke’s essay, “Mina Loy and Househunting: or, Biography as Restoration”).

The 1958 publication of Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables served as a prompt both to Loy and her circle of friends to arrange an exhibition of her artwork, and Marcel Duchamp and Julien Levy worked together to find an appropriate gallery.19 Duchamp recognized the value of Loy’s new work, and likely understood her response to his own use of readymade materials (see the discussion of Duchamp in the Storymap of Loy’s Construction): he decided to nominate Loy for an award from the Copley Foundation for her Constructions, and to apply on her behalf, required copies of her books and photographs of her artwork. In January 1959, Duchamp and Levy visited Loy’s apartment to survey her artwork (which Levy found to be in good shape), and spoke with David Mann about an exhibition.20

By March 1959, Loy’s Constructions had been moved out of her apartment and were under the care of David Mann, who had agreed to an exhibition; the dates for the exhibition had been set; and Julien Levy was working on a press release and list of patrons to sponsor the opening.21 Loy wrote to James Laughlin to ask whether David Mann could “exhibit” her poem “Hot Cross Bums” at the request of Duchamp, a re-use of the poem which would require Laughlin’s permission. This letter suggests that Duchamp was quite involved in the curation of the exhibition, and that like Loy, he understood the Bowery-era poems and Constructions as part of the same verbal-visual collection.22

Julien Levy and Marcel Duchamp designed the exhibition announcement, and both in their own fashion emphasized the poetry of Loy’s Constructions:

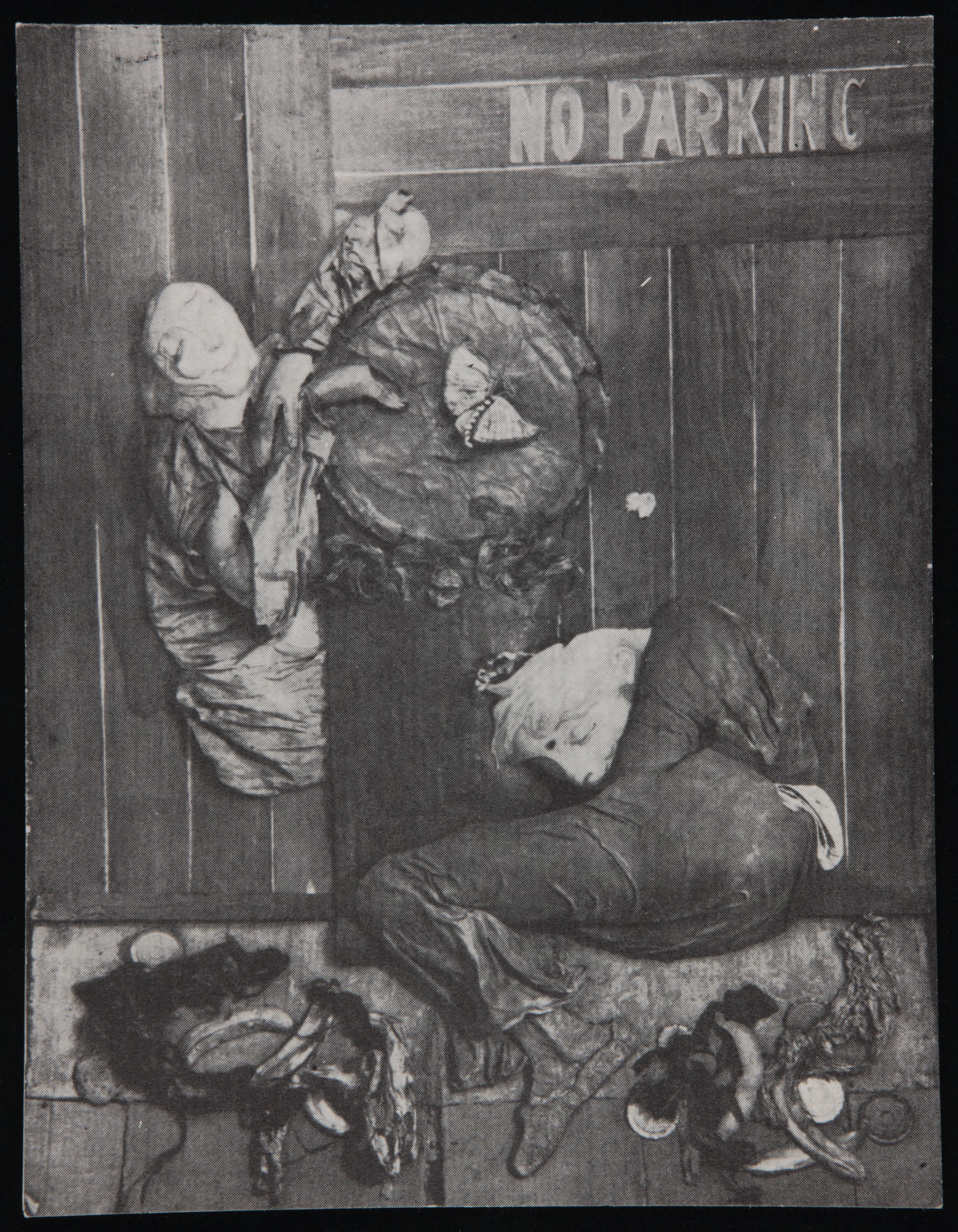

Accounts of the gallery opening suggest that it was well-attended. Julien Levy reported to Mina Loy by letter that Peggy Guggenheim purchased a Construction, and that Djuna Barnes, Coates, Walter Starky, Bob Brown, Hans Fraenkel, [Steve] Ferris, Lipshitz, William Maas, Sidney Janis, Oscar Williams, Kay Boyle, Gilbert Seldes, and Alexander Blossom, all attended.23 Carolyn Burke also mentions that Joseph Cornell and Frances Steloff, founder of Gotham Book Mart, attended the opening, and that Mina Loy telephoned to speak with her friends, just as she had for her 1958 book party (434). Frances Steloff, who had known Loy from her Greenwich Village days and shared Loy’s interest in Christian Science, created a related “exhibition,” a front window display at the Gotham Book Mart which featured Loy’s construction “No Parking” (included on the exhibition announcement) and Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables (Burke 399, 434).

Take a guided tour of a Mina Loy Construction ca. 1950s

Carolyn Burke has summed up the contemporary reviews (434-435), which were not enthusiastic.24 Loy’s works were out of sync with — or once again ahead of — the times: in 1958-9 the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition of abstract expressionism, The New American Painting, toured eight European countries. “Poetry” in painting, decisively linked by Clement Greenberg to the influence of Surrealism, had been rejected in favor of a pure abstraction.25 In a ca. 1959 letter to Jonathan Williams, Loy mentions that Duchamp has arranged an exhibition of her work at the Bodley Gallery that Williams might like to attend, but adds that “perhaps you would not care for anything that is not – although new – not abstract.”26

Yet by the estimation of a different circle of admirers who appreciated the expansive understanding of poetic art that emerged out of Dada and Surrealism, Loy’s Bowery constructions had taken avant-garde experiment in a decidedly new direction. Thanks to Duchamp’s and Levy’s efforts, Mina Loy was awarded “the Copley Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement in Art” (Burke 435). Levy and Duchamp, imaginative curators of avant-garde exhibitions, had helped to ensure that Mina Loy’s artistic as well as poetic legacy would continue.27

In a twist typical of Loy’s career, the Constructions that didn’t sell at the Bodley Gallery disappeared from public view for decades. They were stored in Julien and Jean Levy’s barn in Connecticut until a fire prompted their removal to a storage locker.28

The unsold Constructions remained in this storage locker for almost forty years, until they were rediscovered by Roger Conover.

Read Roger Conover’s account of this discovery.

Roger Conover took up the task begun by Mabel Dodge and Carl Van Vechten, Gilbert Neiman and Jonathan Williams, Julien Levy and Marcel Duchamp, of collecting, editing, and publishing the works of a poet-artist who both desired and resisted making her work public, or rather, who wanted to reach the public on her own terms, even while dependent on others to make this contact possible.

Carolyn Burke, in following the trail of Loy’s life and career as she conducted the research for her biography, came into possession of Loy’s Construction “Househunting” through Peggy Guggenheim, and oversaw this fragile work’s restoration.

Read Carolyn Burke’s “Mina Loy & Househunting, or Biography as Restoration”

Amy Elkins has recently discovered and published Berenice Abbott’s photographs of a number of Loy’s Constructions as they were displayed in her Stanton Street apartment, including three previously unseen Constructions.29 Further Constructions may well turn up in the future.

Loy’s peripatetic life and career, the scattered nature of her archive, and the ephemerality of many of her designs, has rendered any collection of the elusive “Mina Loy” necessarily fragmentary and incomplete. Yet as her work came back into the public eye in the late 1950s, Loy’s two “collections” — a book of poems, an exhibition of her Constructions, which in Loy’s understanding were parts of a poetic whole — invited a rethinking of what public collections do. Troubling the line between word and image, visibility and disappearance, experimental art and democracy, Loy’s late work challenged her audience to leave behind the well-trodden path through the museum — the “frame or glass case of tradition” (LLB82 297-8) — to navigate the overlooked poetry of the urban streets, a “museum without walls” (Malraux). This was the museum of the en dehors garde, and through it Loy found a space for her work.

- For instance, in a 1930 letter to Julien Levy written soon after Jules Pascin’s death, Loy writes that Pascin’s last words to her were “a scolding — because I wasn’t writing poetry — while my poetry was the only poetry that had as high a value as Paul Valery — on ne peut pas contenter tout le monde! [one can’t please everyone]” In this letter she also comments (with arch humor) on her recent poem, “If you poor darling can’t see that ‘The Widow’s Jazz’ is a great poem — I’m — well — I just shrug my shoulders — Just as ‘The Apology of Genius’ is a great poem.” Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 3. In a letter to Jonathan Williams Loy referred to her “Bowery masterpieces” in quotes: her humorous awareness of this seeming oxymoron nevertheless conveys Loy’s sense that she had made unprecedented works.

- Both Roger Conover and Cristanne Miller have remarked on the small number of poems that Loy published in New York. Conover states, “Mina Loy was never interested in administering her own poems […], and from the 1920s on, she rarely did. She published only ten poems in the last thirty-five years of her life, all solicited” (LB82 xxx). Cristanne Miller points out that “Loy published no poetry at all between 1931 and 1946 and began to write again only in 1941” (193).

- Marisa Januzzi’s annotated bibliographies of works published by and about Loy provide a detailed publication and reception history of the poet, and are necessary reading for any student of Loy trying to understand the arc of her public career. Roger Conover’s Introductions to both LLB82 and LLB96, along with his detailed Editor’s Notes on the editorial, publication and reception history of the poems in LLB96, are a crucial resource. Sara Crangle’s “Introduction” and “Notes” to The Stories and Essays of Mina Loy contain detailed histories of drafts of unpublished works, and for published texts, histories of their publication and reception. Carolyn Burke’s biography provides an overview of Mina Loy’s life and career built on scrupulous research and interviews with Loy’s family, friends, and acquaintances. Burke’s biography is an invaluable resource for the history, context, publication, and exhibition of Loy’s writing and art. In addition, Cristanne Miller considers Loy’s work and career alongside those of two other modernist women, Marianne Moore and Else Lasker-Shuler, providing a comparative reading of their modernist careers.

- Loy’s repeated yet unsuccessful attempts to get James Laughlin, founder of New Directions, to publish her surrealist novel Insel, is a good example. I speculate that Loy’s inability to secure an exhibition for a group of her surrealist-inspired paintings in the mid-1930s influenced her critical stance on Surrealism in her novel Insel, which can be viewed as an alternate space of exhibition (see “I’m not the museum”). Roger Conover quotes from Loy’s 1930 letter to Joella and Julien Levy about her failure to place her 1930 poem “Jules Pascin” with Hound and Horn editor Bernard Handler, who had invited a submission but passed on the poem (LB96 207).

- Linda Kinnahan and Deirdre Egan have both discussed “Compensations of Poverty” as a coherent collection.

- Levy’s informal role as agent began in the early 1930s. Levy secured two of Loy’s Paris publications “Lady Laura in Bohemia” and “The Widow’s Jazz” in Pagany in 1931, after Loy had sent the poems to Joella with the request that Joella take them to Thayer and Marianne Moore at The Dial. See Roger Conover’s Editor’s note, LB96 203-205; see also Linda Kinnahan’s discussion of the circumstances of this publication, which involved Levy’s agreement to permit publication of some Atget photos in Pagany if Loy’s poems were also published (Mina Loy and Twentieth-Century Photography 152). In a June 21, 1951 letter to Mina Loy, Levy states that he showed her poem “Hot Cross Bums” (New Directions 1950) to his neighbor Philip Rahv who thought it magnificent, and asked for a poem for Partisan Review. (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 3, Folder Mina Loy to Joella and Julien Levy, ca. 1950-54). Levy subsequently submitted “Idiot Child on a Fire-Escape” to Partisan Review where it was published in 1952 (LB96 209).

- I discuss the exclusions of the New American Poetry and their effect on American literary histories in “Modernism: the Next Generation.”

- See Januzzi, “Bibliography” 525; Burke 403-4; Conover LB96 210.

- The poems that appeared in Between Worlds were “Property of Pigeons” (1961), “Photo After Pogrom” (1961), “Time-Bomb” (1961), “Faun Fare” (1962), “Impossible Opus” (1961), “Negro Dancer” (1961), and “In Extremis (Show Me a Saint Who Suffered)” (1962) (Januzzi, “Bibliography” 526). Roger Conover writes that “they were the last poems she published anywhere during her lifetime […] Neiman’s effort is remarkable only because it indicates how different the published record might have been had other editors taken similar initiatives” (LB96 211).

- Loy’s response to Laughlin’s 1948 invitation can be found in Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 6, Folder “James Laughlin: Letters from Mina Loy.”

- See “I’m not the museum” for a detailed discussion of the correspondence between Loy and Laughlin about Insel.

- See Jonathan Williams’ essay in The Nation May 27 1961 (461-2) about meeting and publishing Mina Loy.

- A further mediation and “collection” of Loy’s voice is connected to Jonathan Williams. In 1965 while Williams was a poet in residence in Aspen, Robert Creeley and Paul Blackburn visited (they knew Williams from Black Mountain College). While in Aspen, Blackburn interviewed Mina Loy with Robert Vas Dias of the Aspen Writers’ workshop, and recorded their interview, which can be heard through Pennsound (See Burke 436-438).

- Suzanne Zelazo argues for Loy’s use of a similar collage method in both her Bowery poems and collages: “by troubling normative conceptions of dimensionality, Loy’s assemblages underscore the material and textual aspects of language explored in her collage-inflected poetry, creating new and interdisciplinary ways of reading and writing” (50).

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 7, “Williams, Jonathan: Correspondence.”

- An April 29, 1954 letter from Levy to Loy refers to Loy’s letter expressing concern about her Constructions. In his reply, Levy reminds Loy that since he lacks his own gallery (the Levy Gallery closed in 1949) he would make inquiries at the Jolas Gallery and the Hugo Gallery, and reassures Loy that he will press for a show. A January 29 (no year) letter from Levy to Loy mentions Duchamp’s recent marriage to Teeny Matisse, which dates the letter to early 1955 (the marriage took place in 1954). In this letter Levy mentions his efforts to arrange an exhibition for Loy’s Constructions, and names the Jolas Gallery and also David Mann’s Gallery as possibilities.

- Loy wrote Cornell (September 26, 1955) from Aspen, thanking him for an “object card” that he had sent her, and commenting, “I heard you were displeased with my trion pictures — which however some people appreciated deeply — one man said he’s seen the God in them. Now you know this is Mina Loy writing you — do give me news of you — had many exhibitions?” She signed the letter “Longing for news of you artist.” Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 4, Joseph Cornell Folder. Carolyn Burke writes that Steve Ferris apparently contacted galleries on Loy’s behalf and that Cornell came to view the constructions, but reportedly said that given their frail condition his dealer would not want to exhibit them. See Burke 433-4 on the details of the Bodley Gallery exhibition.

- See Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The letters between Julien Levy and Mina Loy are located in theJulien Levy folders in Boxes 6, 7, 8. See also Box 4, “Berenice Abbott, Letter and Interview” and Box 6, “Djuna Barnes: Letters.”

- In a letter to Loy, Julien Levy reported that neither he nor Duchamp needed a commission for this work as both were “in love with” Mina Loy (Burke 433-4).

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. See the December 24, 1958 letter from Julien Levy to Joella Bayer (Box 3), and the January 19, 1959 letter from Julien Levy to Mina Loy (Julien Levy folders, Boxes 6, 7, 8).

- A March 10, 1959 letter from Julien Levy to Joella Bayer mentions these details. In an undated letter to Joella Bayer, Levy discourages her from sending Loy to the opening, given her fragile health and his concern that the show might disappoint her, given the fragility of her constructions. Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 3 “Correspondence.”

- As the creator of The Large Glass (1915-1923) and the accompanying notes on the Glass collected in The Green Box (1934), Duchamp stated that “the final product was to be a wedding of mental and visual elements” (Tomkins, Duchamp 296). Duchamp like Loy used the interplay between word and image to resist the visual allure of the artwork as a commodity framed by the museum, inviting the intellectual response of the spectator in an effort to create a dynamic experience of art in a “museum without walls” (see “Brides Stripped Bare”). In a ca. 1960 letter to Joella Bayer, Levy mentions that while Mina Loy has thanked him many times for the Bodley Gallery exhibition, he wonders whether she has also thanked Duchamp who was “chiefly responsible.” Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 3 “Correspondence.”

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. “Julien Levy Correspondence.” Boxes 6, 7, 8.

- The New York Times stated that the “alliance between Dada and social commentary is downright sinister” and Art News pronounced the constructions “theatrical trappings dripping with sentimentality”(quoted in Burke 434-5).

- As Ellen Levy demonstrates, Clement Greenberg’s influential quest for a purified abstraction in his essays of the late 1930s and early 40s resulted in an effort to purify and separate the disciplines of visual art and literature, to “hunt” the arts “back to their mediums” (Criminal Ingenuity 6-8, 11, 129-133). But this was hunting with a clear winner, painting, whose ascendancy Greenberg championed (Levy). In particular Greenberg conflated Surrealism with a poetic contamination of the “superior” drive towards painterly abstraction (Laocoon 37). Greenberg argued that the branch of Surrealist art relying on the Surrealist image (Ernt, Tanguy, Roy, Magritte, Oelze, Fini, Dali) introduced new subject matter but not a “new way of seeing”: he argued that “the Surrealist image provides painting with new anecdotes to illustrate […] it has promoted the rehabilitation of academic art under a new literary disguise” (Horizon 54). More pointedly, in conflating Surrealism with poetry, Greenberg attempted to “write the Surrealists out of the history of modernism” and to write “literature out of the history of modernism altogether” (Levy 132; 8).

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 7, “Williams, Jonathan: Correspondence.”

- On Levy’s and Duchamp’s experimental exhibitions see Lewis Kachur, Displaying the Marvelous.

- In letters from Julien Levy to Joella Bayer dated December 17, 1963 and January 18, 1964, Levy states that he has stored the works in his barn, covered in plastic. In an April 18, 1969 letter to Joella Bayer, Julien Levy mentions that his barn has collapsed and asks whether he should ship or store the two cases of Loy paintings. In a letter dated May 6, 1969 Joella Bayer refers to their phone conversation and reiterates her permission to have the artwork crated and stored. Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. “Correspondence” Box 3.

- As Elkins notes in her PMLA essay, “the photographs are the only truly contemporary images of Loy’s assemblages that show them the way Loy herself chose to display them, revealing Loy’s particular orientation of her artwork” (1095). Given the importance of Loy’s unconventional installations of her artwork, including in her Paris apartment, Abbott’s photos provide crucial insight into Loy’s alternative, “en dehors garde” museum (see “I’m not the Museum”).