In which we consider how Stieglitz came to Dada,

with Duchamp playing ambassador of New York Dada

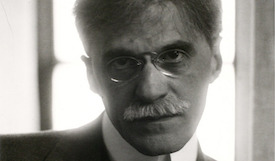

“To scholars of both Dada and Stieglitz,”Jay Bochner observes, “it has seemed that [Stieglitz] was critical of the extremes of Dada and entirely unreceptive to its shenanigans.”1 It’s easy to see why. Stieglitz’s earnest, idealistic stance and sensuous, earthy photos seem like the polar opposite of Duchamp’s cool, evasive poses and abstract, cerebral artistic experiments.

Contending that “the differences between the two men’s aesthetic positions would always remain vast,”2 Debra Bricker Balken positions each at the helm of “two distinct aesthetic factions” of the American avant garde: “Alfred Stieglitz, the proponent of an intuitive and sensuous approach, and Marcel Duchamp, the champion of a more cerebral form of artistic investigation” (Balken 34, 18). Their “contrasting sensibilities” come into sharper focus in their own statements about art.3 Whereas Stieglitz asserted that, “Art begins where thinking ends” (qtd by Balken 63), Duchamp professed, “I was interested in ideas…I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind” (qtd by Naumann 43).4

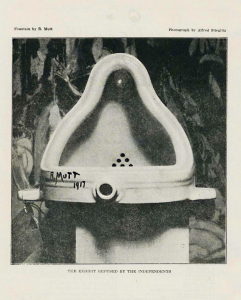

When Duchamp arrived in New York in 1915, he found Stieglitz too stern and serious for his taste: “He always spoke in a very moralizing way,” Duchamp recalled, “He didn’t amuse me much at the beginning. I must say he didn’t think much of me either; I struck him as a charlatan” (qtd by Balken 40).5 But though the two artists may have been skeptical of one another from afar, according to Duchamp, “when we met in 1915 we got on very well, at once. From then on all went splendidly between us. He had my ‘ready-made’ R. Mutt figure at 291 when it was pushed aside by the Society of Independent Artists in 1917. He also photographed it” (qtd by Norman).6

Jay Bochner illuminates the common ground between the two artists. Although Stieglitz was more idealistic and physical, and Duchamp was more “ideatic” in his interest in abstract ideas, both “contrived to dispossess the market of the art object” and both “insistently goaded a sleepy, self-satisfied public.”7 What united Stieglitz and Duchamp under the umbrella of Dada was an interest in removing art from the elites and handing it over to the American public.

From its initial inception to its intended dissemination, Stieglitz’s iconic “The Steerage” (1907) illustrates his democratic, anti-commercial stance. Stieglitz recalled his first encounter with the scene: “I stood spellbound for a while. I saw shapes related to one another—a picture of shapes, and underlying it, a new vision that held me: simple people; the feeling the ship, ocean, sky; a sense of release that I was away from the mob called rich” (qtd by Norman 76). In this account, abstract shapes and patterns lead Stieglitz’s imagination to a more visceral contact with the physical world and its human inhabitants. Later, Stieglitz “agreed to have The Steerage appear in 291, to see what the American people would do to it if left to themselves,” but he insisted that he “made no attempt to solicit orders nor to sell the magazine” (qtd by Norman 127).

In this seminal work and throughout his career, Stieglitz sought to spur new ways of seeing and make contact with real, “simple people,” all while evading commercial entanglements. According to Bochner, similar democratic ideals had motivated Stieglitz more than a decade earlier to form Secession, an avant-garde collective that sought to foster a “link between modern art and modern society, as if not to let commerce run away with the whole culture.”8 Indeed, throughout his career, Bochner explains, Stieglitz worked toward three main ideals: the recognition of photography as art, the formation of a distinctly American tradition of modern art, and the “education of the American public to make them see spiritual and emotional value in individual, native work not distorted by the marketing of art” (“Eros Eyesore” 106).

Although Duchamp’s provocations are more ironic than Stieglitz’s photographs, they also attack the elites—the critics and connoisseurs who guard the gateways to the high art. Duchamp inserts everyday objects into this sacred realm, turning them over to the public to accept or reject. For the readymade to have its effect on art,” Bochner explains, “much depends on its finding its way to a public that will decide whether or not it can be allowed into the inner circle of art” (“Eros Eyesore” 103).9

Michael Taylor argues that the urinal in particular “was explicitly chosen for its shock value, and was intended for public rather than private consumption”; Fountain was “a deliberately provocative ‘blague’—a premeditated joke in plastic form, designed to flush out the hypocrisy of the Society’s professed liberal idealism” and expose it to the American public (Taylor 206). Duchamp’s “blagues” defy authority and incite laughter, and as Joseph Stella remarked in 1921, “To poke fun at, to break down, to laugh at, that is Dadaism” (qtd by Naumann 200-1).

Michael Taylor argues that the urinal in particular “was explicitly chosen for its shock value, and was intended for public rather than private consumption”; Fountain was “a deliberately provocative ‘blague’—a premeditated joke in plastic form, designed to flush out the hypocrisy of the Society’s professed liberal idealism” and expose it to the American public (Taylor 206). Duchamp’s “blagues” defy authority and incite laughter, and as Joseph Stella remarked in 1921, “To poke fun at, to break down, to laugh at, that is Dadaism” (qtd by Naumann 200-1).

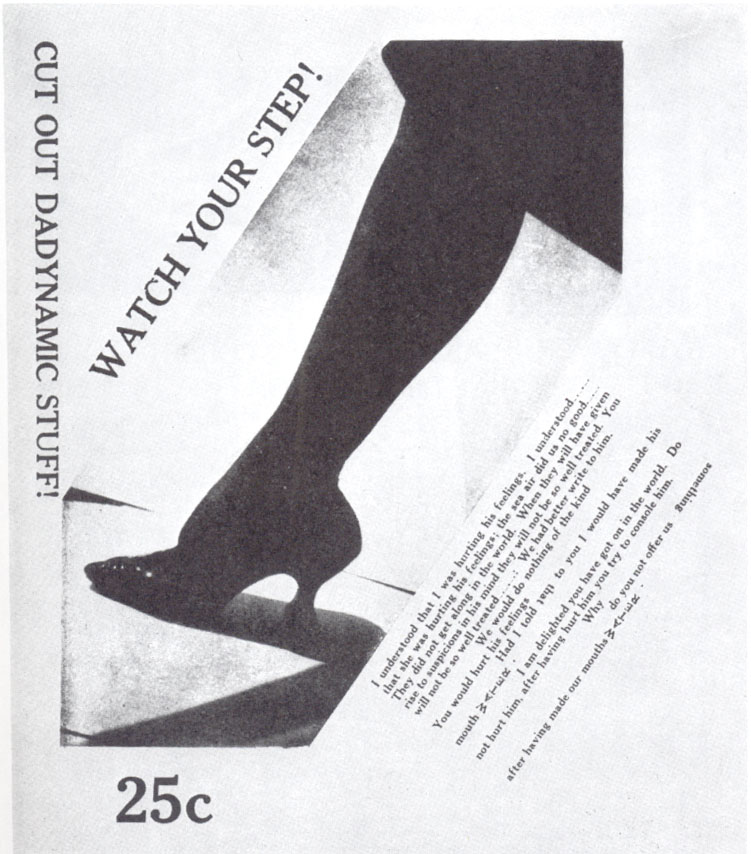

For all his high seriousness about the cause of art, Stieglitz got the joke, writing to Duchamp and Man Ray in response to their magazine New York Dada: “It’s quite a marvel…—The cover is a delight…—The skit—Hartley—Mina Loy—Stella—most amusing—and Francis’s letter a real message—It’s all a prod” (qtd by Bochner 215).

- Jay Bochner, An American Lens: Scenes form Alfred Stieglitz’s New York Secession, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005, p.215

- Debra Bricken Balken, Debating American Modernism: Stieglitz, Duchamp, and the New York Avant-Garde, New York: American Federation of the Arts, 2003, p. 62.

- Michael R. Taylor, “Blind Man’s Bluff: Duchamp, Stieglitz, and the Fountain Scandal Revisited,” Mirrorical Returns: Marcel Duchamp and the 20th Century Art, ed. by Yukihiro Hirayoshi (Osaka: National Museum of Art, 2004), p.209.

- Stieglitz made this remark in a 1926 public address; see Herber Seligman, Alfred Stieglitz Talking: Notes on Some of His Conversations, 1925-1931 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966), 110. Duchamp’s remark was recorded in “Eleven Europeans in America,” ed. by James Johnson Sweeney, Bulletin 13, Nos. 4-5 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1946), 20.

- This remark is recorded in Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. by Ron Padgett (New York: Viking Press, 1971), 54.

- Dorothy Norman, Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer, New York: Random House, 1973, p.123.

- Jay Bochner.“Eros Eyesore,” In Debating American Modernism: Stieglitz, Duchamp, and the New York Avant-Garde, Ed. by Debra Bricken Balken, New York: American Federation of the Arts, 2003, p.113.

- Jay Bochner, An American Lens: Scenes form Alfred Stieglitz’s New York Secession, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005, p. 118.

- Rosalind Kraus similarly argues that, “the readymade logic itself was aimed squarely in the realm of high art in order to reveal the sense in which art was already caught up in the system of exchange and of the deracination of objects by removing them from their original sites in order to circulate them within the rootless conditions of the museum” (251).