In which we introduce our principle dancers,

poet Mina Loy and photographer Alfred Stieglitz

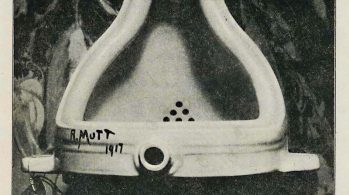

Mina Loy and Alfred Stieglitz take the stage together in May 1917, in The Blind Man 2, the proto-Dada little magazine issued in conjunction with the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. The issue celebrates Fountain, a urinal submitted under the pseudonym of R. Mutt, purportedly by Marcel Duchamp, which had just been rejected by the exhibition organizers.1 The Blind Man 2 not only contains the only surviving photograph of the lost urinal-turned-high-art, but also sheds light on Loy’s migration from Italian Futurism to New York Dada, and her en dehors garde turn toward the American public.

Loy, Futurist femme fatale lately arrived from Firenze, and Stieglitz, great American patriarch of straight photography, seem like an unlikely pair in this proto-Dada dance. Although they had been moving in the same avant-garde circles since January 1914 when Loy made her literary debut in Stieglitz’s Camera Work with “Aphorisms on Futurism,” their adjacent publications in Blind Man seem diametrically opposed.

Loy’s contribution, “O Marcel – – – otherwise I Also Have Been to Louise’s,” is a fractured transcript of conversational snippets from a soirée.2 The gossipy compilation indulges in flagrant name-dropping. In addition to foregrounding “Marcel” [Duchamp] and “Louise” [Norton] in the title, the piece mentions “Mina” [Loy], “Clara” [Tice], “Carlo” [William Carlos Williams], and [Charles] “Demuth,” all members of Walter Conrad Arensberg’s exclusive salon (14-15).

Immediately following Loy’s compilation, Stieglitz’s letter to “My dear Blind Man” calls for anonymous submissions to the next Independent Society Exhibition. Stieglitz advises “withhold[ing] the names of all the makers of all work shown,” and putting “in the place of the names of artists, simply numbers” in the exhibition catalog (15).

“Oh Marcel,” Loy’s flippant, ironic transcript seems like the antithesis of Stieglitz’s earnest, idealistic letter. Her name-dropping banks on the power of name recognition; his call for anonymity refuses to trade on its commercial value. Her compilation is random and incoherent; his letter is rational and logical. Her speakers sound drunk; his tone is sober. What could possibly draw such disparate performances together on the Dada stage?

A version of this chapter was first published in French, under the title, “Pas de Deux: la danse dada de Mina Loy et Alfred Stieglitz,” in the collection, Carrefour Stieglitz: Colloque de Cerisy-la-Salle, sous la direction de Jay Bochner et Jean-Pierre Montier (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012), 325-338. I would like to thank Jay Bochner and the participants of the colloquium for their generosity and insights into the world of Alfred Stieglitz.

- While the prank has long been attributed to Ducahmp, recently art historians have argued that the Baroness Elsa Von Frietag Loringhoven was the Dada provocateur behind “Fountain.” See Josh Jones, “The Iconic Urinal & Work of Art, “Fountain,” Wasn’t Created by Marcel Duchamp But by the Pioneering Dada Artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven”, Open Culture, July 5, 2018.

- Loy also explored the conversational medium in her experimental play The Pamperers, which she wrote between 1915 and 1917. The script begins with “Tag Ends of Overheard Conversation,” from which the characters and drama materialize.