In which we consider how Loy came to Dada,

with Duchamp playing ambassador of New York Dada

According to lore, Mina Loy was powerfully attracted to the Italian Futurists: she “woke up!” under their electrifying influence, but was ultimately repelled by their misogyny.1 As I argue in “Courting an Audience: Loy’s Plays,” Loy’s critique of the Futurists was actually more complex than this legend admits. She rejected not only their “scorn of woman,” but also their arrogant attitudes toward audiences. Her 1915 plays “Collision” and “Cittábapini” satirize Futurist hubris, and their publication in the decadent, pre-Dada, American little magazine, Rogue, signal Loy’s increasing distance from the Futurists and growing affinity with the New York avant-garde.

Loy sailed to New York in 1916, seeking both romantic fulfillment and a public she could embrace, rather than mock and antagonize. Once there, she found herself as attracted to Marcel Duchamp and Dada as she had been to F. T. Marinetti and Futurism (and when she met Dada icon Arthur Cravan, much more so).

Although Burke says Duchamp’s “contrepetteries”—bilingual sexual puns—put Loy in an “awkward” position (218), and Marisa Januzzi interprets “O Marcel” as “the first bit of feminist criticism on Duchamp,”2 Roger Conover asserts that Loy and Duchamp “had much in common besides a mattress” they shared with Beatrice Wood and two other revelers the night of the Blindman’s Ball, including “a distrust of doctrine and…distaste for bourgeois values.”3 Januzzi likewise contends that Duchamp was “the proximate irritant for some of [Loy’s] most creative and ultimately profound considerations of the verbal and visual terrain: the emergent mediascape in which Dada staked its claims” (Januzzi 596-7).

Beyond their shared “interest in constructions and destructions of female virginity” (Januzzi 597), Loy must have recognized Duchamp’s female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy, as a kindred spirit to her own pseudonymous masks: “Gina,” “Imna,” and “Ova,” to name just a few (for more on her pseudonyms, see Loy’s Signature Style). Man Ray’s 1923 photograph of Rrose Sélavy bears a striking resemblance to an unsigned photo of Loy published in the Little Review in 1920 and probably also taken by Man Ray (below).4

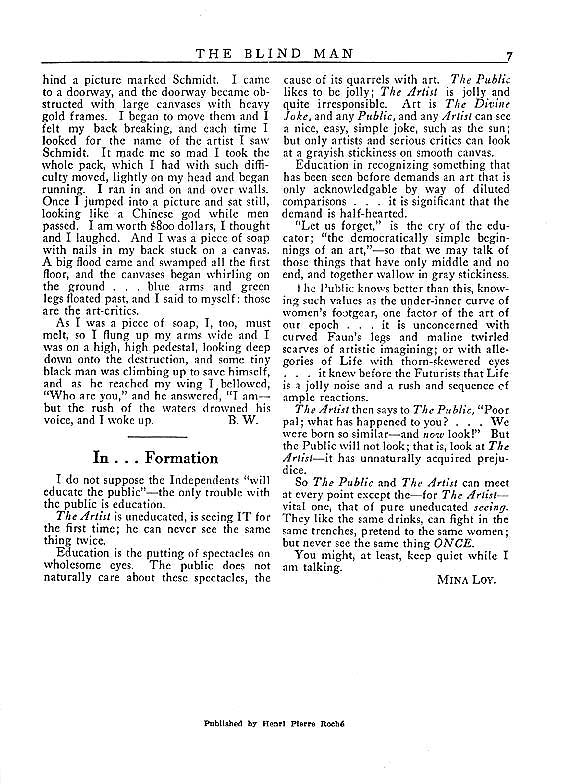

Loy also shared Duchamp’s interest in using humor to prod the public. “In…formation,” an essay she wrote for Blindman I, asserts the possibility of an amiable relationship with her audience, more akin to Dada’s jocularity than to Futurism’s scorn. Her use of ellipses in the title deconstructs the business of giving “information,” implying that education enforces conformity. To deliver information is to align people in formation.

Loy defends the public against the prejudicing influence of education: “I do not suppose the Independents ‘will educate the public’,” she writes, “—the only trouble with the public is education” (7). If the public would remove the “spectacles” put on by education, they might return to their “wholesome” vision. Here, Loy may be punning on the double meaning of spectacles as both eyeglasses and performances, implying that the educated public should not be distracted by the spectacles they’ve been educated to desire. Uncorrupted by training, the public, Loy insists, is naturally sympathetic to new and irreverent art:

The Public likes to be jolly; The Artist is jolly and quite irresponsible. Art is The Divine Joke, and any Public, and any Artist can see a nice, easy, simple joke, such as the sun. (7)

If you got that joke, you’re a Dada natural, because it makes no sense. It makes nonsense. Which is nice, easy, simple, and jolly.

Quick-witted Loy recognizes the irony of her position as a writer instructing the public to reject their educations: she concludes her piece by ironically assuming the pedantic pose of a lecturer and scolding, “You might, at least, keep quiet while I am talking” (8). The ambiguous tone of this closing remark cuts both ways, calling attention to her didacticism and her audience’s inattention, and provoking us to reassess her remarks in a more humorous, skeptical manner. The multilayered tone is typical of Loy’s en dehors garde pose: she is at once affectionate, witty, ironic, and self-implicating.

- Carolyn Burke, Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1996, p. 178-9.

- Marissa Januzzi, “Dada Through the Looking Glass, or: Mina Loy’s Objective,” In Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, Ed. by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1998, p.583.

- Roger L. Conover, “(Re) Introducing Mina Loy.” In Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, Ed. by Maeera Schreiber and Keith Tuma, Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation, 1998, p.257.

- The Little Review does not give a photo credit, but the photograph resembles another by Man Ray reproduced in the appendices of Mina Loy, Lost Lunar Baedecker, ed. by Roger Conover (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1996), 167