Jazz emerged out of African American history and experience and was shaped by the contact between African, European, and American musical forms. Thus from its start in New Orleans, jazz embodied and gave voice to cultural mixture and to the promises and limitations of democracy, in particular the African American struggle for freedom and civil rights. As jazz traveled across the Atlantic to Europe during and after World War One, black musicians often encountered greater freedom and acceptance than in the U.S., but nevertheless were subject to the fashion for, and racist stereotypes of, the exotic and the primitive1 (on Negrophilia, Négritude, Afro-Surrealism, see “Surrealist Histories.”).

Petrine Archer-Straw has chronicled the negrophilia of white avant-garde artists in Paris as they responded to African American jazz:

In the case of 1920s Paris we are faced with a doubling act: whites act out what they think is black, based on stereotypes. The difference between the negro’s and the negrophile’s acting is that one is about material survival, while the other is about the survival of art poetry and fantasy. Jazz facilitated this transformation; celluloid gave it permanence. The images remain long after the party is over, an eerie reminder of possibilities. (Negrophilia 105)

Archer-Straw makes an important distinction between the performances of African American jazz musicians and the representations of jazz by the white avant-garde, who commonly relied on stereotypes of racial primitivism. These stereotypes are present in the work of Mina Loy, who was inspired by listening to jazz in New York and Paris, and wrote about jazz as central to American modernism. However, her representations of jazz present an additional doubling act, as many of her images simultaneously reinforce and resist racist stereotypes of primitivism. This section explores how Loy’s position as a woman on the margins of the Surrealist avant-garde influenced her engagement with jazz and race.

Nancy Cunard’s Negro: An Anthology, Surrealism, Mina Loy

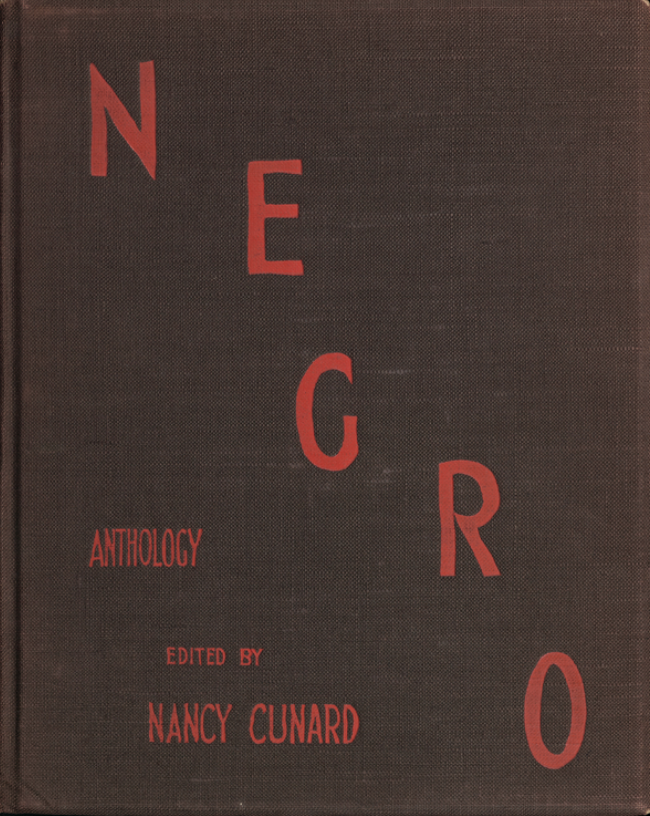

Poet, publisher, journalist, and political activist Nancy Cunard’s Negro: An Anthology (1934) emerged from Cunard’s commitment to racial equality but was simultaneously shaped by the negrophilia of the Parisian avant-garde. Reflecting on the aims of the anthology, Cunard stated “It was necessary to make this book — and I think in this manner, an anthology of some 150 voices of both races — for the recording of the struggles and achievements, the persecutions and the revolts against them, of the negro peoples” (“Preface” iii). As Petrine Archer-Straw points out, although “Cunard promoted the publication as representing a collaboration between the ‘two races’, the majority of its contributors were of African descent” (Negrophilia 167). The contributors to the anthology addressed black history, sociology, politics, music, art (sculpture, film, dance, theater), and poetry, chiefly in the U.S., but also in Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Emphasizing the anthology’s dedication to Pan-African racial justice, and to the ongoing struggle against imperialism and the legacies of slavery, Cunard wrote, “the chord of oppression, struggle and protest rings, trumpet-like or muffled, but always insistent throughout” (“Preface” iv).

Contributors to the anthology were associated with a number of intellectual and political traditions, including Surrealism, Communism, the Harlem Renaissance, and Négritude. Although the anthology did not originate with the Surrealist movement, a number of Surrealists wrote essays, with Samuel Beckett supplying the translations from French to English.2 The Surrealist contributions to the anthology can be considered as an early archive of Afrosurrealism, understood as “an anthologizing denomination that designates a surrealism that is Black, or rather, a surrealism for which race and politics form its constitutive priority” (Eburne). Cunard’s association with the Surrealist avant-garde in the 1920s and early 30s shaped the anthology’s politics: she included the Surrealists’ anti-colonialist tract “Murderous Humanitarianism” in a section on Europe (see “Afrosurrealism”), and she wrote a number of essays that commented on and sought to intervene in racial injustice, including “Scottsboro — and other Scottsboros” (Negro Anthology 245).3 Although Cunard never joined the Communist party, in her “Preface” she indicated her sympathy with Communism, which she felt could eradicate racial as well as class distinctions (Negro Anthology iii), a sentiment shared by many Surrealists in the early 1930s (Friedman, “Introduction” xv, xxvii; Chisholm 106-7). Maureen Moynagh points out “Not only does Cunard reiterate this connection in her own contributions, she devotes two sections of the anthology to the topic, and several of her contributors, black and white, were Communist Party members or fellow travellers” (“Introduction” Essays 15).4

Just as Surrealism and its affiliation with Communism influenced Cunard’s political stance, Cunard’s negrophilia — particularly the view that “blacks belonged to a primitive chaotic order rooted in nature that needed to be maintained for their cultural authenticity” (Archer Straw, Negrophilia 170) — aligned her with members of the Parisian avant-garde who looked to African “primitive” cultures to “replenish and revitalize European culture,” thus perpetuating “racist myths” (Negrophilia 94).5 Cunard’s essays criticize the history of European and American colonialism and racism, but she simultaneously “idealized and stereotyped black vitality and the ‘shoeless state’” (Archer Straw, Negrophilia 170).6 This contradiction characterizes many of the contributions by the Parisian avant-garde, laying bare the schisms and divergent backgrounds and viewpoints that shaped Negro: An Anthology.7

The avant-garde’s negrophilia was particularly evident in the anthology’s essays on jazz, which were included in sections on “Music” and “Negro Stars” (vi). As Robin Kelley and Franklin Rosemont argue, “as early as 1919 the appearance of African American jazz in France was a notable historic event for André Breton and his friends and was duly recalled as such thirty-one years later in the group’s Surrealist Almanac (1950)” (Black, Brown, and Beige 6). In Belgian Surrealist Robert Goffin’s essay “Hot Jazz,” translated by Samuel Beckett, Goffin emphasized “the analogy between the acceptance of ‘hot’ and the favour enjoyed throughout Europe by the Surréaliste movement” (Negro Anthology 239). Defining “hot jazz” as “improvised jazz” (Negro Anthology 238), Goffin pursued the analogy:

Is it not remarkable that new modes both of sentiment and its exteriorisation should have been discovered independently? What Breton and Aragon did for poetry in 1920, Chirico and Ernst for painting, has been instinctively accomplished as early as 1910 by humble Negro musicians, unaided by the control of that critical intelligence that was to prove such an asset to the later initiators. (Negro Anthology 239)

Relying on stereotypes of African American jazz musicians’ “primitive,” “untrained,” “natural,” and “unconscious” expression (Negro Anthology 239), Goffin ignores the “critical intelligence” and conscious engagement with cultural traditions at work in jazz, so as to support the analogy between musical improvisation and the kinds of unconscious and automatic expression prized by the Surrealists. Nevertheless his attempt to forge connections between jazz and Surrealism would reverberate with later Afrosurrealist writing.8

Mina Loy did not contribute to Nancy Cunard’s anthology, but she knew Cunard in Paris, as they traveled in the same avant-garde circles. Loy’s poetic portrait “Nancy Cunard,” written in the 1920s or early 1930s (LB96 103, 205-6), indicates Loy’s interest in Cunard’s life and status as a modernist icon (see “Close Reading by Cristanne Miller”).9 Cunard became an avant-garde poster girl through her careful cultivation of her own image, as in her choice to wear African ivory bracelets stacked from wrist to elbow, signifiers of the exotic and the primitive, a fashion that was covered in London Vogue (October 1927) and immortalized by Man Ray’s 1926 photograph.10 Wendy Grossman comments that “Primitivist fashion was accorded its ultra-modern status with this portrait” (Man Ray 137).11

Man Ray was not the only artist who took Cunard as muse: she was the subject of photographic, painted, and sculpted portraits by Cecil Beton, Constantin Brancusi, Oskar Kokoschka, Wyndham Lewis, Curtis Moffat, Barbara Ker-Seymer, and John Banting, among others. Cunard’s notoriety stemmed from her rejection of her aristocratic British family (she was sole heir to the Cunard shipping fortune) and from her equally dramatic self-fashioning as an independent modern woman devoted to writing and art, radical politics, and sexual freedom. Cunard lived the crossings of boundaries of class, race, sexuality, and nationality that Loy explored in her poem “Lady Laura in Bohemia” (see “Surrealism in Loy’s Paris-era Poetry”), and like Lady Laura, Cunard’s choices invited censure from all sides.12

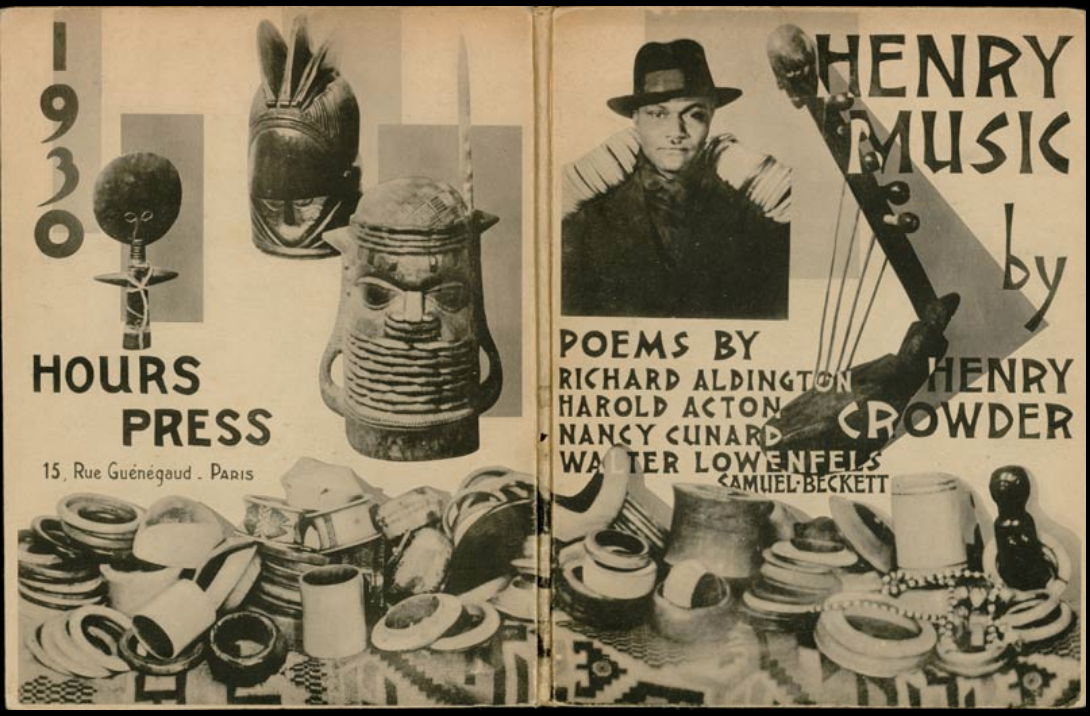

Cunard moved to Paris in 1920 and began her artistic career as a poet with the publication of Sublunary in 1923; like Loy, a fellow “lunar” geographer, Cunard traversed the margins of the Parisian “surreal scene” (Moynagh 21-22, 24-25; Chisholm 103-107). She became romantically involved with Surrealist poet Louis Aragon in 1926, and from 1928 to 1935 was involved with African-American jazz pianist and composer Henry Crowder, who helped her run Hours Press (1928-1931) and inspired her work on the Negro anthology.13 The press published experimental works including “Henry Crowder: Six Piano Pieces with Poems by Richard Aldington, Walter Lowenfels, and Nancy Cunard,” and Henry Music, with music by Crowder and song lyrics by Samuel Lowenfels, Samuel Beckett, and Nancy Cunard, with cover photo and collage by Man Ray. From 1931-33 with the help of Raymond Michelet, Cunard assembled the Negro Anthology, which she dedicated to Crowder, “my first Negro friend” (Dedication, Negro Anthology). Although scholars have chronicled Cunard’s activities as a poet, publisher, and political activist, Cunard remains an “en dehors garde” figure, marginal rather than central to histories of the avant-garde.14

Like Cunard, Mina Loy’s engagement with Surrealism and race in her writing and visual art of the 1920s and 30s was mediated by her experience of jazz in Paris and New York. Loy’s painting Surreal Scene (1930) positions African-American jazz as both instigator and muse for what Loy would later term Surrealism’s “topsy-turvy” experiments. In her 1950 essay on Joseph Cornell’s Aviary exhibition, Loy commented, “[Surrealism’s] theoretic contrivance for somersaulting reasons into an ‘Alicism’ world of topsy-turvy logic greatly entertained me [but] my conclusive reaction to much of it was ‘Black Magic’”(see “Sidewalk Surrealism”).

Loy’s 1930 painting depicts a small, naked black girl who embodies the spirit of jazz. She holds a hose-like “horn” which in Surrealist fashion has both mechanical and organic qualities: the horn’s head resembles a sieve or shower head, while the horn itself tapers off into a long snake-like tail. The girl and her horn-hose clearly make things happen, as the starlike puffs (perhaps signifying musical notes) that emerge from it either pierce or inspire the movement of the neighboring bicycle wheel-woman, a machine-human hybrid similar to the hybrid snake-horn. Loy paints the black girl with an upside-down head, as an impish figure of inversion and misrule, aligning jazz with the “topsy-turvy” spirit of Surrealism in their shared challenge to the rational order of bourgeois society.

But even as Loy’s painting draws connections between jazz and the Surrealist challenge to white, middle-class culture, Loy’s depiction of the girl draws on racist caricatures; like Cunard and the Surrealist avant-garde, Loy simultaneously challenged white European patriarchal culture while representing its black “primitive” other in ways that echoed and perpetuated racist images and stereotypes.

More specifically, Loy’s depiction of a mischievous, naked black girl with pigtails wearing only one shoe echoes racist images of the picaninny (or pickaninny), a figure often shown nude, made famous by the character of Topsy:

The first famous pickaninny was Topsy, a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1850). Like Tom, Topsy was intended to be a sympathetic character, one that would show the reader the evils of slavery. Topsy was a neglected slave girl who, wild, ignorant, and miserable, had been corrupted by slavery. When asked if she knows who made her, she professes ignorance of both God and a mother, saying “I s’pect I growed. Don’t think nobody never made me.” Topsy’s wildness is only tempered by the steady, Christian love of the angelic White child, Eva. Despite Stowe’s noble intentions, Topsy soon became a common character in the minstrel shows of the era, where any sympathetic qualities were replaced by a happy, mirthful, mischievous persona. Topsy’s unkempt physical appearance and poor language skill became comic props. On stage, Topsy became a pickaninny, a child coon. (History on the Net)

The character of Topsy remained pervasive in popular culture, and in 1927, due to Universal Films’ version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Topsy dolls were sold.

Loy’s representation draws on these widely-circulated caricatures of the picaninny, but Loy’s depiction of the figure’s upside-down head suggests that she may also have been drawing on the racial symbolism of the topsy-turvy doll. Elizabeth Pochoda describes the topsy-turvy doll thus:

The reversible, double-ended doll fuses two torsos—one black, one white—at the waist, typically with a long skirt. Turned one way, the doll is black; flipped over so the skirt obscures the black doll, and the doll is white. (“What the Black Dolls Say“)

The doll originated in the nineteenth century, possibly on plantations, and has been interpreted as both subverting and reinforcing racial and sexual hierarchies.15 Julian Jarboe writes,

Either way, the dolls have since the beginning been reinterpreted and appropriated to suit the use of their makers, the children who played with them, and the people who felt they were worth preserving—their purpose was always context-dependent, a moving mirror of racial womanhood.” (“Racial Symbolism of the Topsy-Turvy Doll”)

Loy does not depict a black and white figure, but her portrayal of the girl’s “topsy-turvy” head and her later use of the term “topsy-turvy” to describe Surrealism, suggests that Loy may have drawn on and recognized the implicit surrealism and racial hybridity of the topsy-turvy doll.16 Loy’s topsy-turvy image transforms even as it reinforces the picaninny stereotype: Loy draws out the potential of jazz to unsettle or subvert hierarchies, even as her use of the stereotype reinforces racial and sexual hierarchies, in a double movement characteristic of the topsy-turvy doll and of Loy’s aesthetics.

Loy’s depiction of jazz as a “topsy-turvy” art form resonated with the Surrealist practice of juxtaposing opposed or distant entities, a technique that centered the “surrealist image” and which the topsy-turvy doll, with its two opposed fused bodies, materialized. For Loy, jazz embodied her efforts to generate new, hybrid images and forms involving both sexual and racial mixture and inversion, a motif she not only explored in “Surreal Scene” but also in her poems of the 1920s and 30s, in her novel Insel, and in the surrealist object “Lobster Boy.” Loy describes or alludes to jazz in a number of poems from this era, including “The Widow’s Jazz,” “Crab-Angel”, and “Negro Dancer” (possibly inspired by Josephine Baker).17 In these poems Loy relied on stereotypes of black primitivism in her depictions of jazz, even as she simultaneously transforms them and/or acknowledges the white audience’s appetite for primitivism and the performers’ self-conscious playing to this desire.

For instance, Linda Kinnahan argues that Loy’s poem “Negro Dancer”

recalls the theatrics of Josephine Baker, who performed the ‘danse sauvage’ in Paris during the years of Loy’s residence there. Indeed, the poem’s attention to the dance as performance, in the poem’s final lines, recasts the racialized (and racist) visual signifiers to suggest the dancer’s conscious appropriation of white expectations. In ‘posturing’ the ‘aboriginal innocencies’ [sic] of ‘an overwrought eros,’ the dancer performs blackness ‘in the glare of a theater,’ both a ‘Puppet’ to cultural stereotypes and also, the poem arguably suggests, exceeding them in the ‘cosmic spasm’ that mitigates the ‘glare’ of an artificial racial lens, circulated within a visual set of signifiers. (Loy and Photography 62)

Similarly, in “The Widow’s Jazz,” Loy reinforces stereotypes of the black musicians’ primitivism, even as she observes that the “white flesh quakes to the negro soul,” and challenges the conflation of the primitive with the bestial through the contradictory image of “black brute-angels” (LLB96 96)(see “Surrealism in Loy’s Paris-era Poetry”).18

Loy developed her understanding of jazz as a form embodying hybrid mixture in her 1925 essay “Modern Poetry,” written in Paris and published in Charm magazine. Loy suggests that jazz like free verse embodied a modern American art form that emerged from a democratic vernacular, an “English enriched and variegated with the grammatical structure and voice-inflection of many races, in novel alloy with the fundamental time-is-money idiom of the United States” (LB96 158).19 She argued,

The new poetry of the English language has proceeded out of America. Of things American it attains the aristocratic situation of vitality. This unexpectedly realized valuation of American jazz and American poetry is endorsed by two publics; the one universal, the other infinitesimal in comparison. (LB96 157)

Although Loy noted that jazz is easier than modern poetry “to get in touch with” (LB96 157), and thus has a bigger audience, she emphasized that the two arts spring from a similar source:

Modern poetry, like music, has received a fresh impetus from contemporary life; they have both gained in precipitance of movement. The structure of all poetry is the movement that an active individuality makes in expressing itself. Poetic rhythm, of which we have all spoken, is the chart of a temperament. (LB96 157)

According to Loy, free verse and jazz both enact in their formal designs the “movement” of contemporary life, governed by individual expression and temperament rather than by inherited conventions.

Explaining why “the renaissance of poetry should proceed out of America,” Loy emphasized the “living” nature of the language which “grows as you speak” (LB96 159), enabling jazz-like improvisation and the ability to change the language. Loy added that the

true American […] ingeniously coins new words for old ideas, to keep good humor warm. And on the baser avenues of Manhattan every voice swings to the triple rhythm of its race, its citizenship and its personality. (LB96 159)

Indicating that this “living” American idiom is her muse, she writes: “Out of the welter of this unclassifiable speech, while professors of Harvard and Oxford labored to preserve ‘God’s English,’ the muse of modern literature arose, and her tongue has been loosened in the melting pot” (LB96 159).20

Loy, Race, Insel: Double Images, Coining New Words

Although Loy, like other participants in the largely white Parisian avant-garde, employed stereotypes of black primitivism in her art and writing, she simultaneously criticized the Surrealists’ negotiation of racial and sexual difference in their art and personal lives, a critique particularly evident in her novel Insel (see “I’m not the museum”). In an episode set at the Dôme, the novel’s narrator and protagonist Mrs. Jones demonstrates that the surrealist painter Insel’s assumption of male superiority is upheld by racist beliefs and behavior, a critique she reveals by employing, and subsequently dismantling, a surrealist double image. In this way Loy revealed how surrealists’ beliefs about sex and race fueled their aesthetic preoccupations. By “coin[ing] new words,” a strategy Loy attributed to the “true American” in her essay on modern poetry (1925), Loy offered an alternative to the surrealist double image through a verbal form of hybrid mixture.

Salvador Dali popularized the technique of the double image, which he defined as

such a representation of an object that it is also, without the slightest physical or anatomical change, a representation of another entirely different object, the second representation being equally devoid of any deformation or abnormality betraying arrangement. (James Thrall Soby, Dali 25)

The double image allowed an image to be seen in two ways, much like a visual pun or optical illusion, and many earlier painters such as Arcimboldo had employed it. For Dali, however, the double image was a key technique of his “paranoiac-critical method,” which disclosed — beneath the “real” appearance of things — hidden, unconscious meanings.

Loy’s use and critique of the double image in Insel centers on racial and sexual mixture, and emerges through the protagonist Mrs. Jones’ narration: Jones had been sitting with Insel in a cafe, but left momentarily to buy cigarettes which she placed on the table, before leaving again to apply some rouge:

When I returned it looked as if the empty space in our quiet corner had come alive, the leather padding had broken out in a parasitic formation, a double starfish whose radial extremities projected and retracted rapidly at dynamic angles.

It was Insel all cluttered up with his ‘private life.’ Draped with the bodies of two negresses, spiked with their limbs. They seemed, out of ambush, to have fallen upon him from over the back of the high seat. The waiter had laid a startling oblong of white cloth which knocked the milling muddle of polished black arms and faces round Insel’s pallor into a factitious distance, although he and his mates were actually attached to my supper table. (Insel 79)

Mrs. Jones first describes a moving, double starfish that has emerged from the leather banquette, a fantastical surrealist image that combines objects not conventionally found together. She then reveals the second way to view this image, as “Insel all cluttered up with his ‘private life’”, involved in a struggle with two black women over the possession of Jones’ cigarettes. These doubled images of the women — seen fantastically as “parasitic” starfish or “realistically” as black bodies “spiked” with limbs — position them as animals surrounding and preying upon Insel’s “pallor.”

Loy draws on primitivist stereotypes of the “negresses” as less than human, as animalistic bodies or more reductively, parts of bodies, involved in a primal struggle. However, Loy is also commenting on, not simply reproducing, Surrealist representations of the primitive. Loy emphasizes the contrast between the women’s “polished black arms and faces” and “Insel’s pallor” to underscore the mixture of seemingly opposed entities. This juxtaposition was a common feature of art by white Surrealists featuring white and black subjects, as in Man Ray’s “Noir et Blanche,” a photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse posed next to a polished African mask, published in Vogue in 1926.

Similarly, Man Ray’s photomontage cover for the Hours Press “Henry Music” (1930), a collection of Crowder’s jazz compositions and poems they inspired, features a photographic portrait of pianist Henry Crowder in a black suit surrounded by Nancy Cunard’s arms, covered in her famous African ivory bracelets.21

Cunard’s braceleted arms are positioned along Crowder’s shoulders, while Cunard’s hands and body are otherwise invisible: the effect of this “double image” — like the starfish in Insel — is to at first glance render Crowder a kind of strange, elephant-like beast with protruding ivory tusks or limbs, and then on second glance, particularly for those “in the know,” to understand that Crowder is encircled by his white lover Cunard’s arms. Cunard’s arms seems to hold or “possess” Crowder as another “primitive” object in her collection of African ivory bracelets, sculpture, and artifacts that surround the photo on the photomontage, and conversely, Crowder seems to “wear” Cunard’s arms as a white ornament or fetish. Man Ray’s double-image portrait of Crowder is meant to scintillate by crossing firmly-drawn cultural lines, including anti-miscegenation laws in the U.S., and does so through reliance on stereotypes of racial and sexual difference. Through the simultaneous fusion and distinction of Cunard and Crowder, Man Ray’s photo positions interracial relationships as shaped by an erotic desire generated by the difference between Africa and Europe, black and white, the “primitive” and the “civilized.” Man Ray’s cover frames “Henry’s Music,” and jazz more generally, as emerging from and giving voice to this juxtaposition, as envisioned by the white avant-garde.22

Man Ray’s double image portrait and photomontage depend on juxtapositions that put racial and sexual differences into play without interrogation. Loy’s criticism of the double image as deployed by Surrealists such as Man Ray hinges on several further transformations of the double image with which the Dôme scene in Insel began. The initial double image — depicting a moving double starfish and a human struggle for cigarettes — positions Insel and the women as part of one creature and/or one physical entanglement. However, as the episode unfolds, Mrs. Jones offers further images of this mixture, which allows her to visually disentangle the women from Insel as she critically probes the nature of their relationship:

As I watched this virtually prohibited conjunction with a race whose ostracism ‘debunks’ humanity’s ostensible belief in its soul, I scarcely heard the scandalous din they were making […] ‘Maquereau!’ “Salaud!’ shrieked the dark ladies to stress their pandemonium accounting of benefits bestowed.

‘Insel,’ I addressed him authoritatively, not dreaming ‘pimp’ and ‘skunk’ were almost the only French words familiar to the poor dear, ‘if you could understand what they are calling you – you’d let go!’

Once more fallen sideways off himself like his own dead leaf in one of those unexpected carvings into profile; a zig-zag profile of a jumping jack cut out of paper from an exercise book; shrunken to a strip of introvert concentration blind as a nerve among the women’s volume, clenching his gums in a fearful sort of constipated fervor, as if hammering on an anvil, Insel thumped his closest negress with an immature fist. Every thump drove in my impression — as this black and white flesh glanced off one another — of their being totally unwed — that Insel, whom I often called ‘Ameise’ [ant] who was even now like an ‘ant,’ occupied with his problem of a load in another dimension, could never have worked on those polished bodies than with the microscopic function of a termite — unseeing, unknowing of all save an imperative to adhere –to never let go. He clung to my cigarettes conscious of nothing but his comic ‘tic.’ (Insel 79-80)

In this image of the struggle Mrs. Jones distinguishes rather than melds “black and white flesh”: the women and Insel appear “totally unwed,” a distinction emphasized by differences in material, scale, and force. Jones depicts Insel as a small ant or termite that swings an “immature fist” and makes “microscopic” efforts to fend off the women, while she describes the women as voluminous “polished bodies,” language that renders them statuesque, as strong and impenetrable as metal.23 With this imagery Loy emphasizes the lack of melding or integration between the black and white bodies, which are “unwed” literally and figuratively. “Unwed” also connotes Insel’s sexual relationship with the women, which — given their exclamations of “pimp” and “skunk” — suggests inequality and exploitation, reversing the initial image of the women as parasites preying on Insel. The waiter informs Mrs. Jones that ‘the fellow lives off these women of the Dome; there’s bound to be a scrap every now and then” (82), and Insel subsequently reveals that he has slept with one of the women three times and had three meals at their expense (90).

As Mrs. Jones begins to pry apart black and white, fact and fantasy, Insel advances his understanding or “version” of what Mrs. Jones terms “the piebald mix-up,” a re-visioning of the scene which he presents to Mrs. Jones the following day at the Gare d’Orleans:

The place seemed deserted. There was no one to see Insel lay out hocus-pocus negresses on the table in apologetic sacrifice.

‘They were all wrong,’ he brooded, as if he were a puritan with an ailing conscience. ‘I was going in the wrong direction! — I renounce,’ he sobbed hurling off the negresses, who, bashed against the dingy windows of the Gare, melted and dripped like black tears into limbo down a morbid adit leading to underground platforms — there to mingle with the inquietude of departure to be borne away on a hearse of the living throbbing along an iron rail which must be a solidified sweep of the Styx. (Insel 88-89)

Mrs. Jones’ imagistic vision of this scene in the train station conveys Insel’s effort to morally condemn the women in the strongest possible terms by putting them on a train to hell, while locating himself — “a puritan with an ailing conscience” — above, on the platform of righteousness. Jones’s description of the women as melting and dripping “like black tears” in Insel’s vision implies that Insel treats the women as malleable flesh or black wax, which he can mold into any shape he needs. Mrs. Jones, however, rejects Insel’s manner of disentangling himself from the women, commenting, “The only thing wrong with those negresses was your beating one of them up!” Indeed, Mrs. Jones’ vision of Insel’s efforts to morally distinguish himself from the women emphasizes the physical violence that Insel must exert to enforce his hypocritical moral distinction.

Mrs. Jones subsequently reveals and challenges the sexist and racist beliefs that guide Insel’s treatment of the women and what he calls “the etiquette of my underworld — its laws” (Insel 89). In doing so she demonstrates that Insel lives off of the prostitutes not as a controlling pimp but as a feeble parasite, offering a different perspective on the entanglement of black and white, female and male bodies in the initial scene. Insel states “The rights of such women extend only to the level of the tabletop” (Insel 89), adding, “She may take anything under the table — she can grab a thousand francs from my pocket — it is hers. But to lift anything off the table – ausgeschlossen! – impermissible!” (Insel 90). Insel expects Mrs. Jones as a white bourgeois woman to accept his worldview: for Insel, “prostitutes lay far beyond a patroness’s permissions,” and, as he states in an unfinished sentence, “Colored people are not—” (Insel 89).

Mrs. Jones quickly dispenses with Insel’s assumption that his racial and sexual “authority” as a white man extends to his economic rights over these women (who he contends may steal but are not owed anything by him): Jones states, “If she had slept with you half a time I consider she has a right to everything you possess” (Insel 89). This passage echoes Loy’s “Feminist Manifesto” (1914) and its critique of the gendered inequality which leads to “parasitism or prostitution,” and may allude to Surrealist René Crevel’s essay “The Negress in the Brothel” published in Cunard’s The Negro: An Anthology.24 Mrs. Jones terms Insel’s “laws” of the underworld “exactly the logic on behalf of woman in the normal world,” pointing out that as far as stealing, “You haven’t got a thousand francs in your pocket” (Insel 90), and that “the waiter told me they support you” (Insel 90). She quips with humor “It’s quite a feat — being a pimp and starving to death […] Whoever heard of a maquereau without any money!” Pricking Insel’s inflated sense of authority and pretensions of control with the needle of her humor, Jones brings him down to size, showing that after all Insel is just an ant, who lives off of the prostitutes not as a controlling pimp but as a small, weak parasite.

Finally, Mrs. Jones’ critical effort to disabuse Insel of his sexist, racist perspective and to provide a more accurate image of Insel’s relationship to the women and of the entanglement of black and white bodies in the initial scene involves replacing the initial starfish “double image” — indebted to iconic Surrealist techniques and imagery associated with Dali and Man Ray — with her own version of doubling, which relies on a verbal amalgamation of unlike things (a strategy that Loy also employed in her poetry at this time). Re-membering the original scene through sound rather than image, Mrs. Jones comments, “It made such a gorgeous sound when they were shouting — almost macrusallo. Like crucified mackerel –” (Insel 91). Mrs. Jones concludes “I shall not call you clochard any more, but macrusallo” (Insel 91).

Combining the words ‘Maquereau!’ (mackerel) and “Salaud!’ (skunk), Loy’s word coinage “macrusallo” creates a “double auditory image”: one can hear the individual words “mackerel” and “skunk,” or more fantastically, one can hear “crucified mackerel” (91), a surreal combination of unlike things. This auditory layering resembles a pun, which may play with different meanings of the same word, or may play with the similar sounds of different words. However “macrusallo”/”maquerau,””salaud” differs from a pun in that the doubling depends on the sound of a new, coined word. Like a pun, Loy’s word coinage generates humor through its doubling, commenting wittily on Insel as a parasite. Both pimps and skunks live off of others (skunks often survive on human garbage), while the fantastical “crucified mackerel” connotes a powerless, sacrificial fish, an animalistic version of Christ transformed and desanctified into what one might eat for dinner. Calling Insel a “crucified mackerel” Mrs. Jones may poke fun at his Puritan moral pretensions, suggesting that the subtext was an ill-concealed use of the women for sex and food.

In “Modern Poetry” (1925) Loy wrote that the “true American” “ingeniously coins new words for old ideas, to keep good humor warm. And on the baser avenues of Manhattan every voice swings to the triple rhythm of its race, its citizenship and its personality” (LB96 159). Mrs. Jones’ verbal amalgamation “macrusallo” replaces the surrealist double image of starfish with a white center and black legs, offering in its stead a feminist mix-up. Even as her imagery reinforces primitivist racial stereotypes, Mrs. Jones extracts Insel from the “negresses” to reveal him as the parasite — a black and white skunk — at the center of the double image.

- See Jeffrey H. Jackson, Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris; William A. Shack, Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story Between the Great Wars; Jeremy F. Lane, Jazz and Machine-Age Imperialism: Music, “Race,” and Intellectuals in France, 1918-1945.

- See Alan Warren Friedman, Ed. Beckett in Black and Red: The Translations for Nancy Cunard’s Negro.

- In addition to “Scottsboro — and Other Scottsboros,” Cunard’s essays in the anthology included “Harlem Reviewed,” “Jamaica — The Negro Island,” “The American Moron and the American of Sense,” and “A Reactionary Negro Organisation.” Alan Warren Friedman writes,“Sentenced to death despite the lack of evidence against them, [the Scottsboro boys] were spared and eventually freed thanks largely to the public protest generated by those, including a very outspoken Cunard, who took up their cause. Because the Communist Party was strongly suportive and the NAACP seemed to her only tepidly engaged, Cunard in Negro exalted the former as the great champion of racial justice, while assailing the latter” (“Introduction” Beckett xv).

- Archer-Straw writes that “Cunard’s dual mission was to communicate and to promote her radical left ideas to blacks in the New World. Thus, Negro’s agenda was set, fashioned and delivered by Cunard” (169). However Moynagh emphasizes the importance of left-wing politics including Marxism and Communism to a number of Harlem intellectuals and Caribbean writers at the time (see “Introduction” Essays 15-16, 54-56). Marcus has explored two of the U.S. State Department files on Nancy Cunard who was under surveillance for her political radicalism (Hearts of Darkness 139-140).

- Archer-Straw comments “The needs of this bohemian subculture inevitably compromised New Negro high ideals, in which ‘Back to Africa’ signaled progressive rather than regressive sentiments. The agendas of the New Negro and the Parisian negrophiles were therefore diametrically opposed” (162-3). Cunard’s essay criticizing the NAACP makes this schism particularly clear, with Cunard’s Communist sympathies one of the dividing wedges (see Moynagh, Essays 59-60, Friedman, Beckett xv).

- Many of the photographs of Cunard from the late 1920s and early 30s distill this contradiction: clothed in tiger skins with her distinctive ivory bracelets, products accessible to her due to the history of imperialism, “Cunard performs a primitivism that fluctuates between identification and appropriation” (Moynagh 25). Indeed Cunard’s performance of primitivism, which in certain photos crossed into a problematic staging of herself as a victim of a lynching or rape, has contributed to her marginalization (see Moynagh 25-26, Marcus 132-3). As Maureen Moynagh points out, “In her efforts to speak outside of imperial constructions of whiteness in her political identification with black struggles, Cunard repeatedly risked a rehearsal of the imperial script” (28). Moynagh adds that Cunard often took up political stances that she hoped would allow her to escape her racial and class privilege, but “the desire for a position beyond race, class and gender is itself marked by the very positions she seeks to evade” (Moynagh 60, 62).

- As Maureen Moynagh states, “One of the values of the anthology, for a contemporary reader, is the way it lays a modernist transatlantic matrix alongside a black transatlantic matrix, for it exposes the extent to which modernism is dependent on not only the “image of the Negro and the idea of ‘race’” but on the labour of blacks and black cultural producers” (“Introduction” Essays 11). Jane Marcus viewed the anthology as “the monumental internationalist forerunner of all our current work in Cultural Studies” (Hearts of Darkness 146), and Alan Friedman calls its, despite “its failings,” an “extraordinary achievement” (Beckett xi).

- See the discussions of jazz in Rosemont and Kelley, Eds. Black, Brown & Beige; see also Jeremy F. Lane, “‘Marvellous Ellington’: Rene Menil, Jazz, Surrealism, and Creole Identity in Wartime Martinique,” in Jazz and Machine-Age Imperialism, 155-179.

- Loy responds to Cunard’s iconicity in her poetic portrait, and Roger Conover suggests that the poem “may well be based on a specific portrait of Nancy Cunard that [Loy] saw alongside portraits of George Moore and Princess Murat in Nancy Cunard’s home on rue le Regrattier, Paris” (LB96 206). Both Cristanne Miller (Cultures of Modernism 116-117) and Linda Kinnahan (Loy and Twentieth-Century Photography 62) emphasize Loy’s attention to re-presenting a culturally mediated, artistically “framed” image of Cunard.

- On the photographs of Cunard and her own self-conscious participation in their staging see Archer Straw, Negrophilia 92-3; Marcus, Hearts of Darkness 124-125, 133-136; Moynagh, “Introduction” Essays 24-25; Friedman, “Introduction” Beckett xiii; Grossman, Man Ray 129-138.

- Grossman writes that “Cunard’s multitude of ivory bangles acted as signifiers for a new kind of modernity, presenting her as a trendy arbiter of taste through her association with African artifacts. These African bracelets had acquired their own notoriety during Cunard’s social outings in London and Paris, thus greatly contributing to the fashionable novelty of the Vogue image” (Man Ray 137).

- The trips that Cunard undertook for the creation of Negro: An Anthology are a case in point; Cunard’s refusal to conform to conventions of gendered, class-based, racial, sexual and political conduct while in New York lead to “a sex scandal in the press” (Moynagh “Introduction” Essays 28-29). The fifteen hundred pounds Cunard received “as a result of English newspapers’ publication of slanderous stories from the American press” helped her to pay for the printing of the Negro anthology (Marcus, Hearts of Darkness 139, 128). Cunard herself viewed this scandal in the press as “an effort to detract from her anti-racist work” (Moynagh 51). Jane Marcus probes how and why the erasure of Negro: An Anthology from histories of modernism and African American literature is connected to Cunard’s Communist politics, her rejection of her family and class background, her inter-racial relationships and her “promiscuous” sexuality, and her primitivist “self-fetishizing” in fashion and photography (Hearts of Darkness 124-127, 143, 146-7). Both Moynagh and Marcus discuss Cunard’s bisexuality and “refusal to conform to the traditional feminine principle of fidelity” (Moynagh 23) as a factor that “both attracted and repelled the male modernists in her circle” (Moynagh 23; Marcus 147).

- See William A. Shack, Harlem in Montmartre, 46-47. On Cunard and Crowder’s relationship, see also Friedman xvi-xviii, Chisholm 116-136. Hours Press also published experimental literature by Pound, Louis Aragon, Laura Riding, Havelock Ellis, Robert Graves, and Richard Aldington. Notably the press published Beckett’s first work Whoroscope (1930).

- Friedman comments that many viewed Cunard as “dangerous” in her violation of sexual and political norms, and notes the irony of her “becoming a cultural footnote” (“Introduction,” Beckett xiv). Maureen Moynagh provides an excellent overview of Cunard’s reception (“Introduction” Essays 18-19). She notes two prominent themes of recent scholarship; the first strain, exemplified by Jane Marcus’s scholarship, emphasizes Cunard’s unjust neglect in histories of modernism and the avant-garde and seeks to rectify this neglect; the second strain, exemplified by the work of Ann Douglas and Michael North, emphasizes that “Cunard remains in the problematic position of white patron to black artists and intellectuals, unable to free herself from a privileged discourse” (19). Moynagh argues that “a more complex and interesting picture emerges when, in taking account of Cunard’s work, we attempt to think race, gender and empire together” (19).

- Pochoda notes that “Patricia Williams calls these mysterious creations, which may have originated in 19th-century plantations, ‘an expressive art form crafted by enslaved women…who birthed children who were the half-siblings of the children of the ‘owners’ who had raped them.’” (Nation link).

- Loy’s preference for the “white magic” of Christian Science versus the “black magic” of the Surrealists also can be read in the context of the Parisian Surrealists’ conflation of “primitive” desires with racial blackness and African cultures. This white magic/black magic contrast may also allude to the topsy-turvy doll.

- Negro Dancer was published in 1961 in Between Worlds, but may have been written during Loy’s time in Paris.

- Goffin’s depiction of Louis Armstrong in “The Best Negro Jazz Orchestras” uses imagery similar to Loy’s in “The Widow’s Jazz”: “Oh you musicians of my life, prophets of my youth, splendid Negroes informed with fire, how shall I ever express my love for your saxophones writhing like orchids, your blazing trombones with their hairpin vents, your voices fragrant with all the breezes of home remembered and the breath of the bayous, your rhythm as inexorable as tom-toms beating in an African nostalgia!” (Negro 181).

- Suzanne Churchill suggests that Loy may have been punning on her last name, Min Alloy.

- Cristanne Miller summarizes well the discussion of what critics including Marjorie Perloff, Elisabeth Frost, and Marisa Januzzi have termed Loy’s “mongrel” aesthetic, involving mixtures of “linguistic registers” and national idioms (163). Miller points out that Loy’s mixture of “the idioms of jazz, popular song, modern slang, and various dialects” figured the “vitality of modern and American life” (as discussed by Loy in her 1925 essay “Modern Poetry”), and would also have connoted racial and ethnic mixing, as discussed by Michael North in The Dialect of Modernism (163). Thus Loy’s attention to her Jewish inheritance in “Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose,” begun while living in Berlin (168), conveys “artistic and intellectual values in conflict with the repressive poetics of bourgeois British Protestantism and conventional art” (168).

- Jane Marcus argues that this photo displays Cunard’s “simultaneous effacement and exhibitionism — saying ‘He is mine, but I’m not there’” (Heart of Darkness 136-7).

- Wendy A. Grossman writes, “The linkage of jazz, African art, and African American culture was prevalent within the contemporary craze for all things black, regardless of national origin or artistic intent, and was an association Cunard clearly intended to convey on the cover of the book conveying her lover’s music” (Man Ray 138). Grossman suggests that Man Ray’s composition of the cover seeks to capture jazz-like rhythms.

- Loy may allude to Dali’s ant imagery in this scene, made famous in his 1928 film with Bunuel, “Un Chien Andalou,” and in his paintings. Loy housed Dali’s “Persistence of Memory” in her Paris apartment prior to shipping it to New York so would have been familiar with Dali’s ants (see “I’m not the museum”).

- Jane Marcus writes that censors insisted that Cunard omit Crevel’s essay, translated by Beckett, from the Negro anthology, but “Undaunted, Cunard had the three pages set secretly by the radical Utopia Press and tipped them in while binding the volume herself. The essay, though not listed in the table of contents, is actually in the printed book — a reminder of her radical resourcefulness” (Hearts of Darkness 139). Beckett’s translation of Crevel’s essay notably uses the term “Negress” like Loy in Insel. In the essay Crevel takes his white countrymen to task for their “hypocritical servility before things as they are” (Beckett 71), the “codified injustice” which enables them to ignore the “social degradation” of black women (Beckett 72) and to continue “playing with the piccaninnies” (Beckett 72). Crevel criticizes the negrophilia of the white, male Parisian consumer: “he demands to be entertained and debauched by the exotic curiosity that lifts him clear of the national fact into an illusion of renewal. Hence the popularity of Martinique jazz, Cuban melodies, Harlem bands and the entire tam-tam of the Colonial exhibition. Nowadays the white man regards the man of colour precisely as the wealthy Romans of the Late Empire regarded their slaves — as a means of entertainment. And of course it is no longer necessary to go to Africa. The nearest Leicester Square, now that our livid capitalism has instituted the prostitution of blacks of either sex, is as free of European squeamishness as was thirty years ago the oasis of Andre Gide’s immoralist” (Beckett 73). Crevel committed suicide in June 1935, purportedly over the rift between communism and surrealism; as a communist, surrealist, and homosexual, Crevel was a victim of the homophobia of both the communist party (Ilya Ehrenburg) and of Breton.