In this section you can explore:

- A Trans-Atlantic Friendship

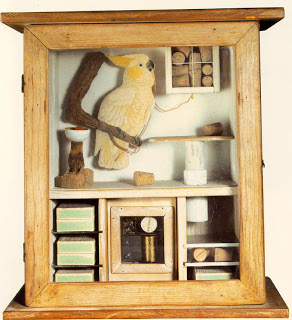

- “Phenomenon in American Art” and Cornell’s Aviary Exhibition

- Sidewalk Surrealism: Loy’s “Property of Pigeons” and Cornell’s Aviary

- Pigeons in Flight: Cornell’s “Aviary” (1955) and “Nymphlight” (1957)

A Trans-Atlantic Friendship

Loy and Cornell established an aesthetic affinity long before they met in person in New York in 1943. Like Loy and Julien Levy, Cornell was a practitioner of Christian Science, and a shared sense of spirituality would cement Loy’s and Cornell’s friendship and inform their approach to Surrealism.1 Julien Levy was the trans-Atlantic conduit between Loy and Joseph Cornell. In Paris in 1932 Levy toured the flea markets with Loy, and when he returned to New York, he gave Cornell the antique puzzle boxes and watch parts he had found; Cornell transformed these parts into small objects and boxes, which Levy featured in his gallery (Burke 379). Cornell became one of Levy’s featured artists: Levy exhibited Cornell’s work in solo shows and group exhibitions from 1932-1943. As a gallery regular, Cornell saw Loy’s 1933 painting exhibition, and on November 21, 1946 he wrote Loy about the “indelible impressions the sky-blue of your painting left mingled with my canvassing experiences in strange out of the way parts of Long Island and Brooklyn” (quoted in Burke 405).

In the 1930s Cornell made two boxes in homage to Loy and Levy. “Portrait of Mina Loy” contains a Man Ray photo of Loy in a top hat, inscribed on the back with the phrase “imperious jewelry of the universe,” a line from Loy’s poem “Apology of Genius,” which was included on Loy’s 1933 Levy Gallery exhibition catalog (Burke, “Loy-alism” 76). Tara Prescott notes that “Cornell assembled several layers of materials, including blue stained glass, a mask cut from a plate illustrating nebulae, glass shards, and a gelatin silver print, to create an homage to Loy and her poetry” (107).2 In this box Cornell presents Loy as both muse and poet; as Tara Prescott observes, the glass shards that cover the Man Ray photo of Loy can be moved around, and thus they “fracture the image of Loy’s face in a myriad of unsettling, intriguing ways, befitting a poet who constantly challenged and redefined her shifting identities” (107). As a result, “the photographs of this piece of art that exist today are all exceptionally different”(107): in the photo above, the shard of glass placed over Loy’s right eye at once frames her eye but also suggests her transformative vision as a poet.

Cornell may also use the movable shards of glass to indicate the dynamic connection between collage and collaboration, a recurrent theme in his friendship with Loy. As Linda Kinnahan writes, “The portrait’s use of a photographic portrait already in existence and produced by a different artist underscores the reproducibility of the photographic image, while insisting upon the artist’s vision through performing a collaboration between Man Ray and Cornell” (Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography 34).

In addition to his boxed “Portrait of Mina Loy,” Cornell sent Loy a small box c. 1935-6 (now lost) which she described in her fictionalized autobiographical novel Insel and which she apparently gave to the German Surrealist painter Richard Oelze before moving to New York in 1936.

This affinity and exchange set the stage for a close artistic friendship in New York beginning in Summer 1943, what Loy biographer Carolyn Burke describes as Loy’s “most fulfilling relationship” (408).3 Cornell, who lived in his family home on Utopia Parkway in Brooklyn, would visit Loy on his trips into Manhattan; they also talked on the phone and exchanged letters. Loy recommended books to Cornell including Alain-Fournier’s novel The Wanderer (1913; trans 1928) and Mary Webb’s 1924 novel Precious Bane (Burke 405-407), both of which would influence Cornell’s work. His thank you letter of August 1, 1943 was itself an epistolary collage, with a cutout Chinese figurine glued onto blue starred paper. In a 1944 letter Loy thanked Cornell for sending his “Crystal Cage,” which had appeared in Charles Henri Ford’s and Parker Tyler’s Americana Fantastica issue of View (January 1943).4

Cornell invited Loy to his exhibitions in New York, including the 1945 Museum of Modern Art exhibition of Portrait of Ondine (Burke 407). He asked for photos of Mina for his “romantic museum,” which he exhibited in 1946 at MoMA as “Romantic Museum, Portraits of Women, Constructions and Arrangements”; although Cornell did not include Loy’s photo, he quoted lines from Precious Bane in the program (Burke 406-407).

If Loy functioned as a kind of muse for Cornell, she was also a crucial conversant about an artistic method both shared, shaped by Surrealist poetics but tempered by Christian Science and a skepticism of Surrealism’s “black magic.” In the 1940s the two exchanged work (Loy sent Cornell her poem “Aid of the Madonna,” he sent her his “Crystal Cage”), as well as thoughts about aesthetic inspiration and method. For instance, on November 21, 1946 Cornell wrote a long letter to Loy about a “lesson in INSPIRATION” (Burke 408), worth quoting at length. He had noticed the “enseigne” on the side of a smoked-fish delivery truck, depicting “a still life of the various stock — fat pieces of meat surmounted by whole fishes in colours that make one think it might at one time have been a bright decalcomania.” He added, “Viewed close up the background sky-blue betrayed beneath the black lettering of a former, less picturesque version of trade-mark, the effect shabby and uninspired like the afternoon.”

With a flash of inspiration, Cornell quickly recalled that he had “glimpsed it in MOTION exactly two years ago for the first time on a beautifully clear shining day on a ride on my bicycle” and “that little still life is still traveling in ‘chambers of imagery’”; he was moved to discover that “it is possible to see ‘lightning strike in the same place’ more than once” (Burke 408). He added,

all of the above seems sometimes so evanescent and nebulous that I have never even mentioned the trifle to anyone. But terms like ‘evanescent’ and ‘nebulous’ are defeatist, are they not, to those who like ourselves are tortured most of the time by their reality? I have generally paid a pretty high price for the above kind of experience, however silly this might sound to some. But way down deep these things can be unconscious, although sturdy, weapons against discouragement. And though my attempt at communication sometimes seems as shabby as the paint on the ‘enseigne’ I can still rejoice that a glorious ‘light’ once illuminated it for me in ‘colours’ never to fade.5

The chance encounter with the faded, peeling decalcomania revealing the lettering of an earlier trademark underneath, and its summoning of the memory of an earlier encounter with this “still life,” seemed to Cornell to crystallize the kind of layered, doubled vision that he hoped to express in his objects and collages: a visible, everyday, even “shabby” reality (the enseigne) is given significance by invisible forces, whether memory, chance, or a spiritual “light.” Cornell’s poetic letter about an ordinary delivery truck becoming the vehicle of the marvellous (“in colours never to fade”) resonated with the kinds of seeing Loy was exploring and defining in poems such as “On Third Avenue.” Cornell understood that he and Loy shared the struggle to express the reality of the “evanescent.”

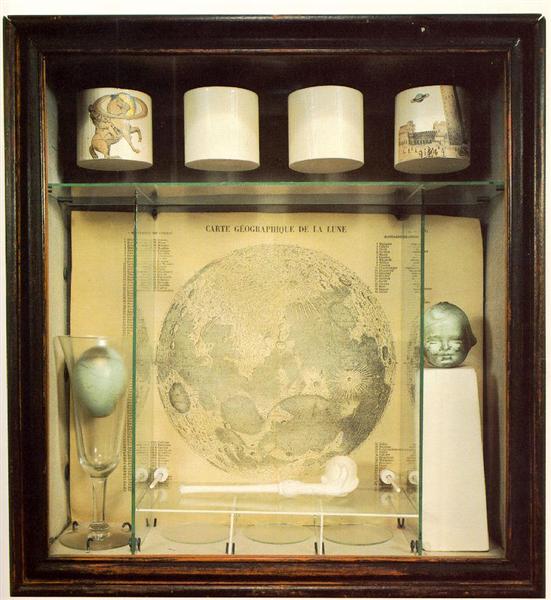

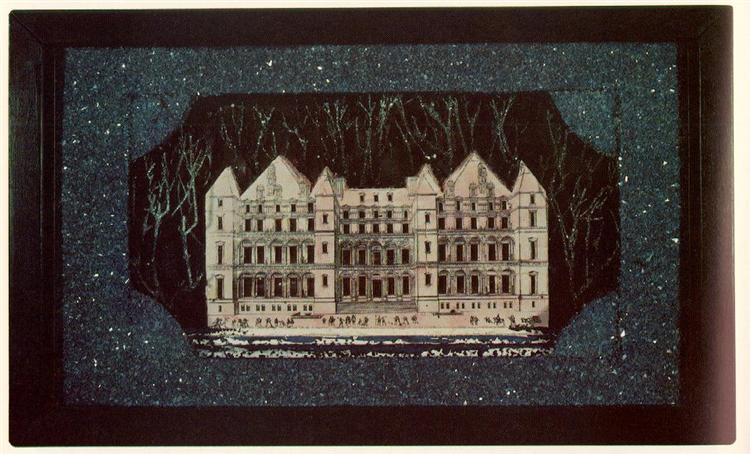

Loy and Cornell shared a method influenced by Surrealism, centered on collage, juxtaposition, and the interplay between word and image, verbal and visual media. Both found artistic and spiritual meaning in the neglected or overlooked materials of everyday life. Both were interested in the constellations and in the “museums of the moon.” Cornell’s Soap Bubble Set (1936), his first “box” of juxtaposed texts and objects — included by Levy in Surrealism (Black Sun Press 1936) and by Alfred Barr, Jr. in MoMA’s Fantastic Art Dada Surrealism exhibition (1937) — seems to realize through its arrangement of objects Loy’s landscape in her 1923 poem “Lunar Baedeker,” and even features a “Carte Géographique de la Lune.” Cornell’s box, like Loy’s poem, reflects on and makes room for a “flock of dreams” that emerges from imaginative dislocation and transformation.

Similarly, both would create alternatives to the official museums of modernism in their collections and assemblages built from materials found around the city, developing the Surrealist interest in found objects and “museums without walls” (Malraux).

In the late 1940s Loy was writing the long poem “Hot Cross Bum” (published in 1950 in James Laughlin’s New Directions) and working on her Bowery constructions. As if recognizing the similarity in their method, Cornell ends a July 3, 1951 letter to Loy, “Enclosed — a ‘hot cross bum’ item.”6 However, as Carolyn Burke points out, “though Cornell’s assemblages had inspired her to evoke the spirit in bric-a-brac, by using junk rather than the scraps of European culture he favored, she was dethroning the idea of art’s belle matière — unseating an art whose status relied on its superiority to humbler forms of expression” (419-20).

In fact, Cornell may not have admired Loy’s constructions as much as he did her paintings shown at the Levy Gallery in 1933: after Loy moved to Aspen in 1953, and Julien Levy and Marcel Duchamp began the work of collecting the assemblages that Loy had left behind in New York, Loy wrote Cornell (September 26, 1955), thanking him for an “object card” that he had sent her, and commented “I heard you were displeased with my trion pictures — which however some people appreciated deeply — one man said he’s seen the God in them. Now you know this is Mina Loy writing you — do give me news of you — had many exhibitions?” She signed the letter “Longing for news of you artist.”7

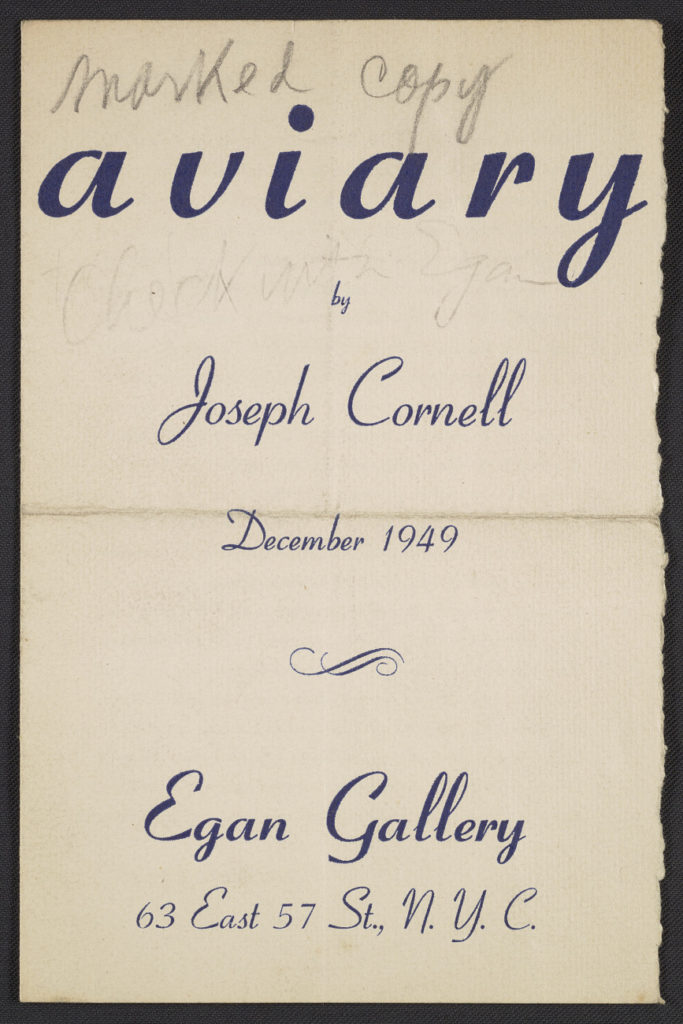

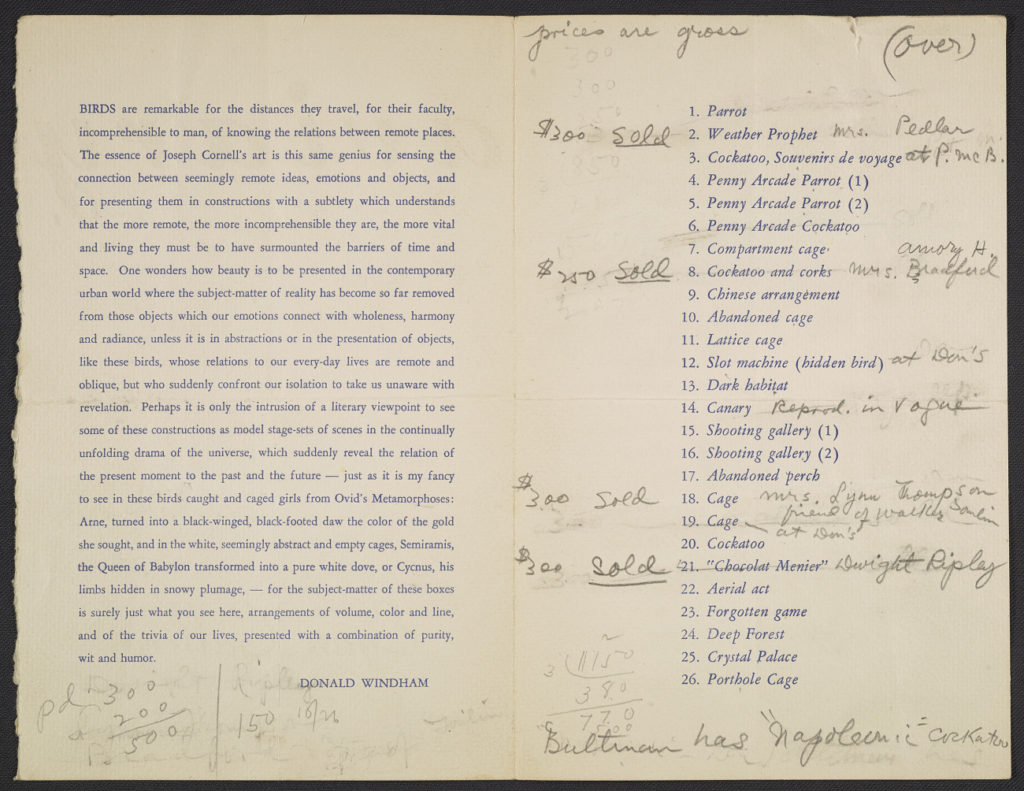

“Phenomenon in American Art” & Cornell’s Aviary Exhibition

The connection between Loy’s and Cornell’s artistic practice would come into focus for Loy in December 1949 when Cornell invited her to his “Aviary” exhibition at the Egan Gallery (December 7 1949 – January 7 1950). In this installation of twenty-six boxes featuring birds, Cornell would begin to explore a new kind of abstraction in his art, one that struck Loy as poetic and spiritual. She was inspired to write a prose appreciation of the exhibition, the first since her essays on Gertrude Stein (Burke 418). The finished essay, “Phenomenon in American Art,” is dated November 25, 1950, and Loy sent it to Cornell (on 11/27/50) who replied (11/29/1950) “how overwhelmed I am with the piece, with the winged words” (Burke 419).

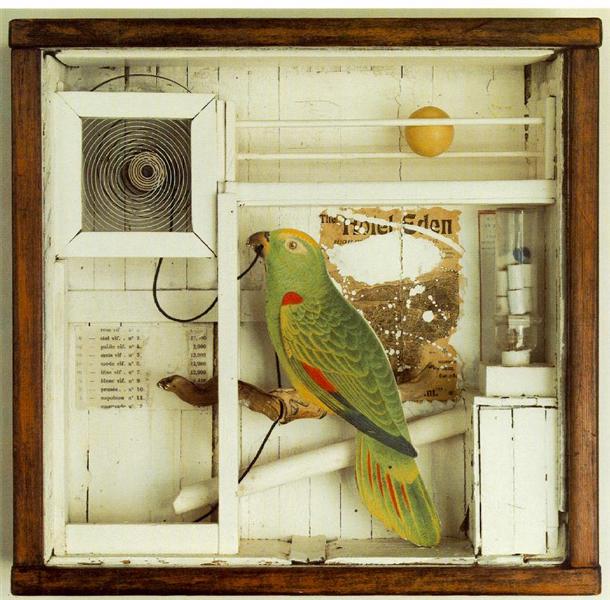

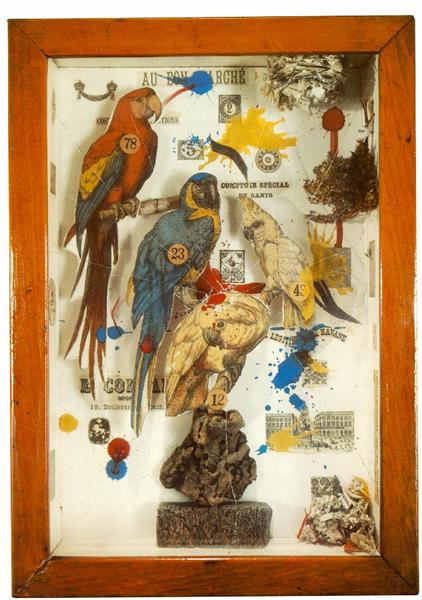

Cornell’s Aviary exhibition featured a variety of boxes resembling “bird houses or cages,” with most boxes containing a “white-painted habitat for a paper cockatoo or parrot […] From one box to the next, the birds variously perch amid a stack of drawers, eye themselves in broken bits of mirror, or listen, bemused, to actual musical boxes hidden behind a wallpaper of old travel posters” (Solomon 186). Cornell arranged the boxes in the Egan Gallery on perches of differing heights, such that the Gallery came to “resemble a bird shop” (Solomon 192).

In “Phenomenon in American Art,” Loy articulates her connections to Cornell’s art, and in doing so clarifies both artists’ relation to Surrealism. 8 Loy begins by establishing the occasion for her essay: “Something insufficiently heeded has occurred in American Art. / The creations of Joseph Cornell” (LLB82 300).9To measure the importance of Cornell’s art, Loy jumps back in time to an equally momentous aesthetic event, her memory of seeing Brancusi’s Golden Bird at Marriette Mills’ home: “A metallic mould of static soaring whose reflections of boughs within Parisian skies beyond her windows gave to solidity an hallucinatory transparence. / Is not the aerial content of a bird partly of the sky?”(LLB82 300). This sculpture, or possibly Brancusi’s photo of the sculpture first printed in the Little Review, inspired Loy’s poem “Brancusi’s Golden Bird,” initially published in The Dial (November 1922) alongside Brancusi’s photo of the sculpture.10

Loy connects Brancusi and Cornell through their uses of abstraction:

It is a long aesthetic itinerary from Brancusi’s Golden Bird to Cornell’s Aviary. The first is the purest abstraction I have ever seen; the latter the purest enticement of the abstract into the objective, even as cubism marks an itinerary of return to composite form, something which cubists predicted would never again preoccupy the artist. Gertrude Stein explained the air of cubism to me as ‘deconstruction preparatory to complete reconstruction of the objective.’ I do not know if anyone considers this reconstruction process yet accomplished. (LLB82 300)

In this brief trajectory through the history of modernist art, Loy suggests that Brancusi’s pure abstraction, routed through cubist deconstruction of the object, has lead to Cornell’s “reconstruction” of the object through abstraction.11

Breton commented in the catalog to the opening exhibition of Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery that “Cornell had evolved an experiment that completely reverses the conventional usage to which objects are put” (Solomon 130; Guggenheim). Loy considers Cornell’s “reconstruction” of the object in the context of the Surrealist movement: “So often L’École declines to petty larceny, the disciple to a pickpocket who picks merely the lining, missing the aesthetic specie” LLB82 300). Her example is Picasso: “How many signs of ennui would have been spared if only Picasso could have copyrighted the Picassian” (LLB82 300).12 Yet Cornell, she implies, was not an obedient Surrealist disciple:

Surrealism was the latest movement to produce a novelty for intellectual concern. Although ethically hindered by its ingenuity of Evil, it was sufficiently valid to take part in that series of ocular surprises propelling the history of art.

Its theoretic contrivance for somersaulting reasons into an ‘Alicism’ world of topsy-turvy logic greatly entertained me [but] my conclusive reaction to much of it was ‘Black Magic.’

From black to white magic in one movement.

For almost as though it had been better described as sub-realism, Cornell, while theoretically adhering to surrealist formula, raised it above reality, achieved an incipience of sublime solidified.13

Instead of merging reality with the unconscious “depths” repressed by civilized society — unlicensed sexuality, anger, irrational violence — with their connotation of “black magic,” Cornell in his Aviary boxes looks to the skies, to “white magic” and to the realm of spiritual longing (see “Topsy-Turvy Aesthetics”).14 The romantic Sublime as that which overwhelms the human capacity of rational understanding here takes on the connotations of the divine, or what Loy calls in her essay “the Kingdom of Heaven.”15 Cornell and Loy in their “white magic” depart in particular from the dissident Surrealists associated with Bataille and the journal Documents, who had split from Breton in 1929 to pursue a less idealizing version of Surrealism, embracing a “sinister love of darkness and monstrous taste for the obscene” including the occult and sadism (Archer-Shaw 143).

While emphasizing Cornell’s departure from Surrealism’s “black magic,” Loy demonstrates Surrealism’s importance to Cornell’s method:

The Futurists’ Boss once insisted to me he had the right to sign his own name to the most revered of masterpieces had he the wits to appreciate them; which might infer that a work of art exists in recognition… […]

Eventually Surrealism qualified this presumption of borrower’s rights. When Max Ernst masterpieced a wonderworld he brought in a new-view by cutting and rearranging dead engravers’ illustrations.

A contemporary brain wielding a prior brain is a more potent implement than a paint brush.

This appropriation of others’ handiwork is not pilfering, but lifting out of the past anothers’ sight tinged with family likeness — aspects added to the original by the altered observation of modern eyes.

Thus the birds in the Aviary, had not to be made by Cornell, they were elected by Cornell, located by Cornell. (LLB82 301)

Loy points out that “Surrealism recognized such effigies of superimposed viewpoints as partial creation, with the imperative to conceive unprecedented ambient for their entire recreation” (LLB82 302). Here Loy restates Ernst’s definition of the Surrealist image as “the fortuitous encounter upon a non-suitable plane of two mutually distant realities” (This Quarter 8). For Cornell, this “unprecedented ambient” is “Simplicity — bits of white wood restrained to retain the entity of weedling, of branching, of foliage, consolatory shade” (LLB82 302). For Loy’s late poems and assemblages, the ambient is equally simple and striking, the sidewalk itself.

In her approach to Cornell’s use of “superimposed viewpoints,” Loy suggests a kind of layered or doubled vision much like the kind Cornell described in his November 1, 1946 letter about the smoked fish delivery truck. As the work of past artists is appropriated and re-seen through the “altered observation of modern eyes,” a constellation is formed between past and present. In fact Walter Benjamin’s definition of the constellation or dialectical image in his Arcades Project, similarly built out of juxtaposed fragments of the past and present, was a key to his method, and constellations as historical, conceptual and imaginative mappings had long interested Loy.

Yet Cornell’s Aviary, Loy suggests, does not simply reveal the relevance of the past to the present but instead “has brought about a crisis: Art’s first intimation of a new potency… to encompass the future” LLB82 302). Cornell’s boxes portray “the consummate arrival of flight.” Thus the trajectory from Brancusi’s Bird to Cornell’s Aviary is important, given the Golden Bird’s futurist qualities. Both works encompass the future through materials that reflect and transform their environment.

More pointedly, both Brancusi’s bird and Cornell’s Aviary boxes use their materiality to capture or “consummate” the immaterial world. Again, Loy describes the Golden Bird as, “A metallic mould of static soaring whose reflections of boughs within Parisian skies beyond her windows gave to solidity an hallucinatory transparence. / Is not the aerial content of a bird partly of the sky?” (LLB82 300). The Golden Bird’s reflective properties allow it to encompass air and sky, defying its “solidity.” Similarly, Loy locates Cornell’s efforts to give material dimension to spirit (the “crystal clue to virtues”) in his use of mirrors,

mirrors so poised to reflect only the anomalous depths of their own brightness in a blackness nevertheless outdistancing diamonds — a hocus-pocus at play with dimension, a depthless surface absorbing all distance, inviolate to what they reflect, outlasting all passing, instantaneously returning to the potential emptiness of their status quo.

The Holy Ghost alit in cloisters with mirrors and meek architecture. Songsters of silence pause before cabinets of Elysian apothecaries whose drawers store only such supreme alleviations as Elixirs of Life, Panaceas of peace. (LLB82 302).

Deborah Solomon sees the role of the mirrors as Cornell’s means of including the spectator in his art; discussing his 1942 box featuring a palace with a mirror backdrop, she writes, “As we see our face reflected in the box’s mirrors, a Renaissance building is brought into the present and made to seem part of that modern cityscape in which passersby glimpse their reflection in shop windows a thousand times a day, and in which every urban voyager is also a voyeur” (141).

In the penultimate line of the essay, Loy turns backwards again, from the works exhibited in the Egan Gallery, to a box that Cornell sent to her in Paris in 1936, and which she in turn gave to Richard Oelze as described in Insel:

“Here,” I hailed the will-o’-the-wisp, “after all I will give you the little box.” This box he desired, it was black, was a small object by the American surrealist, Joseph Cornell, the delicious head of a girl in slumber afloat with a night light flame on the surface of water in a tumbler, of bits cut from early Ladies’ Journals (technically in pupilage to Max Ernst) in loveliness, unique in Surrealism — the tidal lines of engraving cooled its static peace. Under the glass lid a slim silver slipper and a silver ball and one of witch’s blue came raining down on the gray somnolence when one lifted it up.

I should have preferred to keep it myself had I not suddenly realized she belonged in those idle hands to which the unreal Insel intermittently returned. (Insel (1991) 168-169)

In “Phenomenon in American Art” Loy commemorates the same box, with similar language: “Songsters of silence pause before cabinets of Elysian apothecaries whose drawers store only such supreme alleviations as Elixirs of Life, Panaceas of Peace. / Or…the delicious head of a girl in slumber afloat with a night light flame on the surface of the water in a tumbler. Under the glass lid a silver slipper and one of witch’s blue” (LLB82 302). Perhaps seeing Cornell’s boxes in the Aviary exhibition helped Loy to re-see, to understand anew, the box that Cornell had sent her in Paris. By bringing this past object into the present through her essay, Loy creates just the kind of “constellation” she describes as central to Cornell’s art.

Loy may also subtly acknowledge her recognition that she, and many other women, served as Cornell’s muses. Loy’s fascinating long poem “Biography of Songge Byrde” (1952), written after Loy saw the Aviary exhibition, was occasioned by the life of Isadora Duncan who was also a favorite of Cornell’s; in this poem Loy engages the “songge byrde” both as an artist and as a female muse, in conversation with Cornell’s treatment of birds as feminized muses in his aviary boxes.16 In his aviary boxes Cornell associates “the feminine voice and the song of a bird” (Lévêque-Claudet 142).17 Deborah Solomon also writes that Cornell “associated birds with female performers. Birds are curvaceous, clad in feathers, and capable of song, qualities which Cornell’s Aviaries, with their colorful cutouts and actual music boxes, abundantly suggest” (187). If a feminized lyric muse centered the visual designs of the aviary boxes, Loy’s verbal responses to the boxes gives voice to the muse-singer, suggesting that muse and artist are shifting, dynamic positions in an art of re-purposing, which invites and generates further responses. In fact, Loy’s and Cornell’s ongoing artistic dialogue can be viewed as a form of collaboration.

Loy concludes, perhaps reflecting on her earlier description of Cornell’s box in her novel Insel, “So long I have sought a sentence to reproduce the sublimity of Cornell’s objects. Without success. Still, we can take the sublime for granted. After all, it is a sensation. Visitors to this exhibition might gasp on confrontation” (LLB82 302).18 This can be read as Loy’s rueful statement on the failure of words versus images to convey the sublime; however, Loy’s essay on Cornell’s Aviary exhibition suggests a less antagonistic, more reciprocal understanding of the relation between artist and muse, word and image.

Cornell described his method in “Portrait of Ondine” in 1940 as “image-making akin to poetry” and himself as “le chasseur d’images” (Hartigan 75, 83). He thought of his arrangement of found texts, images and objects as a form of “poetics” (Hauptman 91) consistent with Surrealism’s expansion of “the poetic.” His boxes can be regarded as poetic structures containing verbal and/or visual elements that must be brought into poetic relation through the imaginative vision of the spectator. Many of his works (e.g. “Portrait of Ondine”) incorporate both visual and relevant textual materials. Loy’s poems, essays, and fiction respond to many kinds of visual art and media, but her poems written in the 1940s and early 50s were particularly conversant with Surrealist documentary and with the Constructions she was creating out of trash found on the Bowery (see “Collecting Mina Loy”).

Thus the “itinerary” Loy charts from Brancusi to Cornell encapsulates a history of modernism, but also charts her personal artistic journey. Brancusi was a friend of Loy’s in Paris but she also greatly admired his art. Her poem “Brancusi’s Golden Bird” (published in The Dial Nov 1922, 73.5) is an ekphrastic response to Brancusi’s sculpture “Bird in Flight” and possibly to Brancusi’s striking photo of the sculpture first printed in the Little Review, and reprinted on the page facing Loy’s poem in The Dial. Loy’s poem was also exhibited alongside Brancusi’s sculpture at the Brummer Gallery in New York in 1926, solidifying the connection between word and image at the center of Loy’s art. The Levy family’s purchase of “Bird in Flight” after seeing it at the Brummer Gallery initiated Julien Levy’s trip to Paris with Duchamp, where he met Loy and married her daughter Joella, and eventually facilitated the dialogue and friendship between Loy and Cornell.

If Brancusi’s art inspired Loy’s poetry of the early 1920s, Cornell’s friendship and boxes would prove equally important to her writing and art of the 1940s and 50s. Loy’s ekphrastic essay on the Aviary exhibition, like her poem on Brancusi’s bird, articulates values central to her art.19. Her analysis of Cornell’s collage method can be extended to her understanding of word/image relations more generally: “This appropriation of others’ handiwork is not pilfering, but lifting out of the past another’s sight tinged with family likeness — aspects added to the original by the altered observation of modern eyes. / Thus the birds in the Aviary, had not to be made by Cornell, they were elected by Cornell, located by Cornell” (LLB82 301).

In her essay Loy adds a verbal frame or layer to Cornell’s Aviary boxes through the altered observation of her eyes: Cornell’s art thus becomes an element of Loy’s art, which was already a muse for Cornell’s. As Tara Prescott argues, in his “Portrait of Mina Loy” box, “Cornell may have been the first of Loy’s artist friends to put into practice the same collage techniques that she used and apply them to a work dedicated to her” (107). Ekphrasis as employed by Loy in her essay extends into collage and collaboration. In collage we can track a shifting relation between artist and muse, curator and artist, subject and object: Loy and Cornell, like the Surrealists, put into action a collaborative and reciprocal rather than antagonistic relationship between word and image (See “Surrealist Poetics: Word and Image, Collaboration”).20

Sidewalk Surrealism: Loy’s “Property of Pigeons” & Cornell’s Aviary

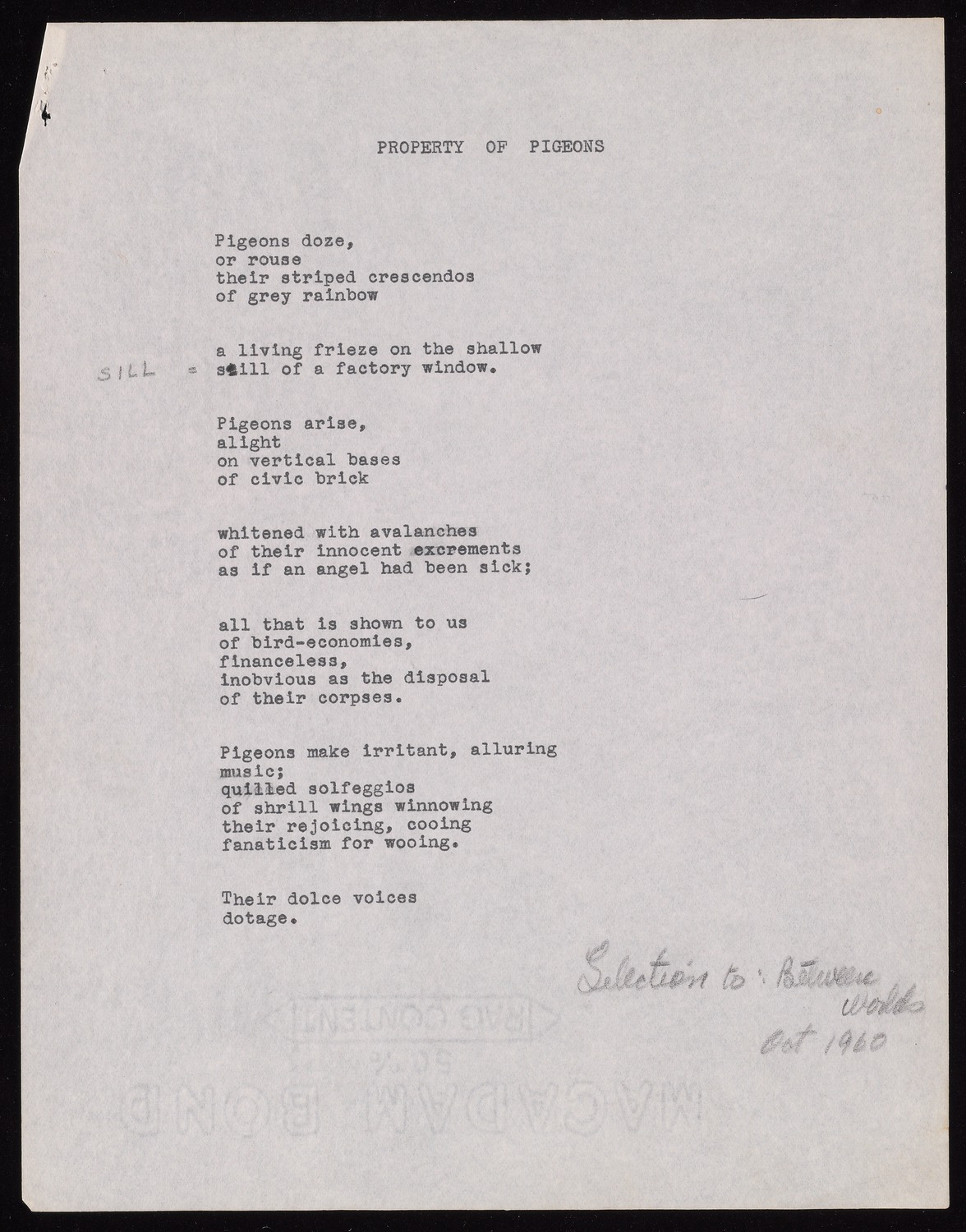

If it was a long trajectory from Brancusi’s Golden Bird to Cornell’s Aviary, that trajectory would take a fascinating turn in Loy’s poem “Property of Pigeons” and in Joseph Cornell’s 1954-5 film made with Rudy Burkhardt “The Aviary,” as well as their 1957 film “Nymphlight,” both of which feature pigeons.

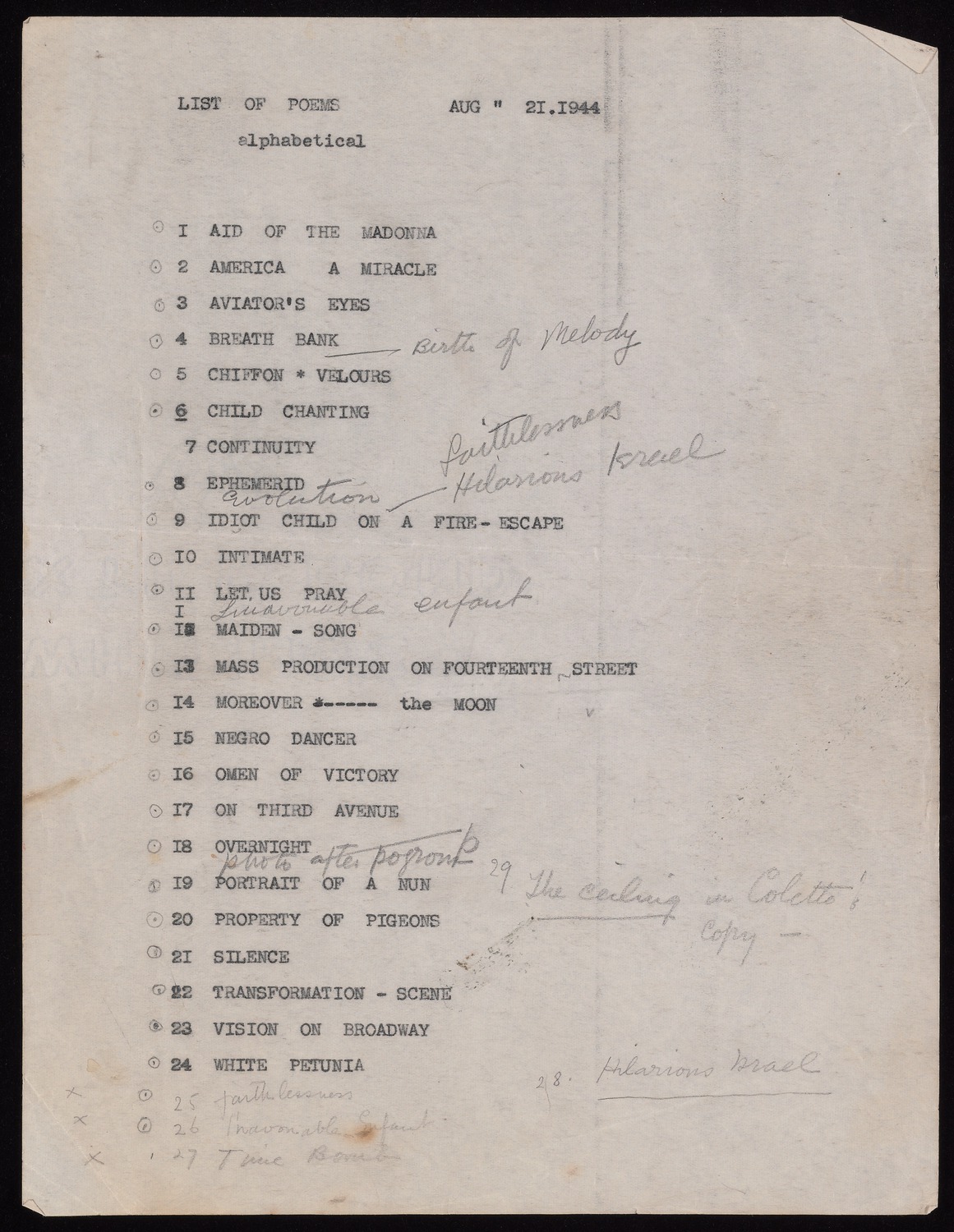

The precise composition date of “Property of Pigeons” is unknown; however, in a list of poems that Loy typed on August 21, 1944, she includes “Property of Pigeons,” so we can assume a date of composition in the early 1940s. Along with a number of other poems from this era, the poem was published by Gilbert Neiman in Between Worlds 1.2 (1961).21 The poem has strong affinities with Cornell’s boxes, his 1949 Aviary exhibition, and his pigeon films. Cornell began making his bird boxes in 1939 with “Fortune Telling Parrot,” followed by a parakeet box in 1941, and a series of owl boxes in the mid-1940s, prior to the parrot-centered boxes exhibited at the Egan Gallery (Solomon 186). Did Loy write “Property of Pigeons” after the consolidation of her friendship with Cornell in 1943, and did Cornell’s early bird boxes influence the imagery of the poem? Did she send or show Cornell a draft of the poem, and if so did the poem influence Cornell’s late 1940s Aviary boxes or his 1950s films featuring pigeons?

We have no record of an exchange about Loy’s poem, and it’s entirely possible that these two like-minded artists independently took the pigeon as muse. Marianne Moore’s “Pigeons” (1935) may be a further influence, and Wallace Stevens’ “Sunday Morning” concludes with “casual flocks of pigeons” that “make / Ambiguous undulations as they sink,/ Downward to darkness, on extended wings.” Moreover, for Loy both the bird and the aviary were long-standing subjects that preceded her friendship with Cornell: Loy’s unpublished, autobiographical manuscript The Child and the Parent begins “with the metaphor of a bird alighting as a symbol of the soul’s appearance in the world” (Burke 354), and contains a chapter titled “Ladies in an Aviary” that depicts Victorian women as birds trapped in their cages.

If the metaphors of bird and aviary were familiar ones to Loy, her experience of “disappearing” into the shuffling shadow-bodies of lower Manhattan would profoundly transform her perspective on both. That Loy chose the humble pigeon as subject of her poem speaks volumes. Pigeons, looked down upon by many city dwellers as scavengers and vessels of dirt and disease, are part of everyday life in the city, omnipresent yet noticed only when they become a nuisance. In this regard they are much like the “shuffling shadow-bodies” of the homeless that Loy chronicled in the city, eking out an existence in an urban, often inhospitable world. For both pigeons and the homeless population, survival entails an adaptation to a concrete environment, and in several of her late collages, Loy depicts homeless men either asleep on the sidewalk or literally trapped beneath the sidewalk, looked down upon and walked over not just figuratively but literally.

But in “Property of Pigeons” Loy does not depict the pigeons as a simple allegorical figure for the homeless; rather she undertakes a shift in perspective that requires a de-centering of the human, a shift that Cornell would also explore in his films centered on pigeons.22 The speaker’s careful observations of the pigeons’ actions in the city structure the poem: “Pigeons doze / or rouse” “Pigeons arise, / alight” “Pigeons make irriritant, alluring / music” “Pigeons disappear” “Pigeons …/..appear to reappear.. / … / to peer….” (LB96 120). As the speaker describes the pigeon’s habits and habitat, she emphasizes the limits of human sight and knowledge, which cannot account for the mysterious ability of pigeons to survive in the city.

Loy begins the poem with two stanzas (Italian for room) reminiscent of Cornell’s bird boxes, establishing an analogy between the visual, spatial design of her poem and the pigeons’ environment:

Pigeons doze,

or rouse

their striped crescendos

of grey rainbowa living frieze on the shallow

sill of a factory window. (LB96 120)

The factory window provides the Cornell-like frame or box in this scene, against which the pigeons make “a living frieze” (a frieze is defined as “a broad horizontal band of sculpted or painted decoration, especially on a wall near the ceiling”). Loy aestheticizes the pigeons with this language, even as she draws attention to the aesthetic incongruity of a moving frieze and the backdrop of the factory exterior. Conventionally friezes are found indoors, yet Loy’s stanzas evoke and challenge the ideals of privacy and containment that we associate with domestic interiors. The line break and enjambment between “shallow / sill” forms an edge akin to the shallow sill: as we read up to and over the line break, we experience a spatial analogy for the window sill, whose shallowness is reinforced by the narrow two-line stanza. In contrast to the exotic birds housed in Cornell’s aviary boxes, the shallow window “box” in Loy’s poem is external, open to the elements, and provides a temporary shelter. A lack of property and private space defines the pigeons’ existence, accentuated by their shelter on the edifice of a factory, where the production of goods helps to fuel the human economy.

The subsequent stanzas form a similar “box”:

Pigeons arise

alight

on vertical bases

of civic brickwhitened with avalanches

of their innocent excrements

as if an angel had been sick; (LB96 120)

In this “whitened” scene reminiscent of the white, abstract background that Cornell would use in many of his Aviary boxes, Loy pointedly ties the color white to pigeon excrement, commonly viewed as a nuisance but here termed “innocent” and angelic. As Tara Prescott points out, Loy’s language transforms the pigeons standing on whitened brick into “tiny feathered sculptures” (184), a kind of marble statuary one might expect to encounter in a museum or civic building. In this unexpected juxtaposition of excrement and innocence, Loy makes visible and challenges understandings of waste as what must be expelled to make cultural and moral “cleanliness” possible (a challenge akin to that of Duchamp’s “fountain”).

Pigeons and their excrement bring into focus human economies, but pigeon economies are more difficult to ascertain; Loy comments that excrement is “all that is shown to us / of bird-economies, / financeless, / inobvious as the disposal / of their corpses.” Throughout the poem Loy uses the anthropomorphizing language of economy and finance ironically, to emphasize the limits of the human perspective on and knowledge of the pigeons (“all that is shown to us”): the human observer knows nothing of the death of pigeons or the disposal of their corpses.23

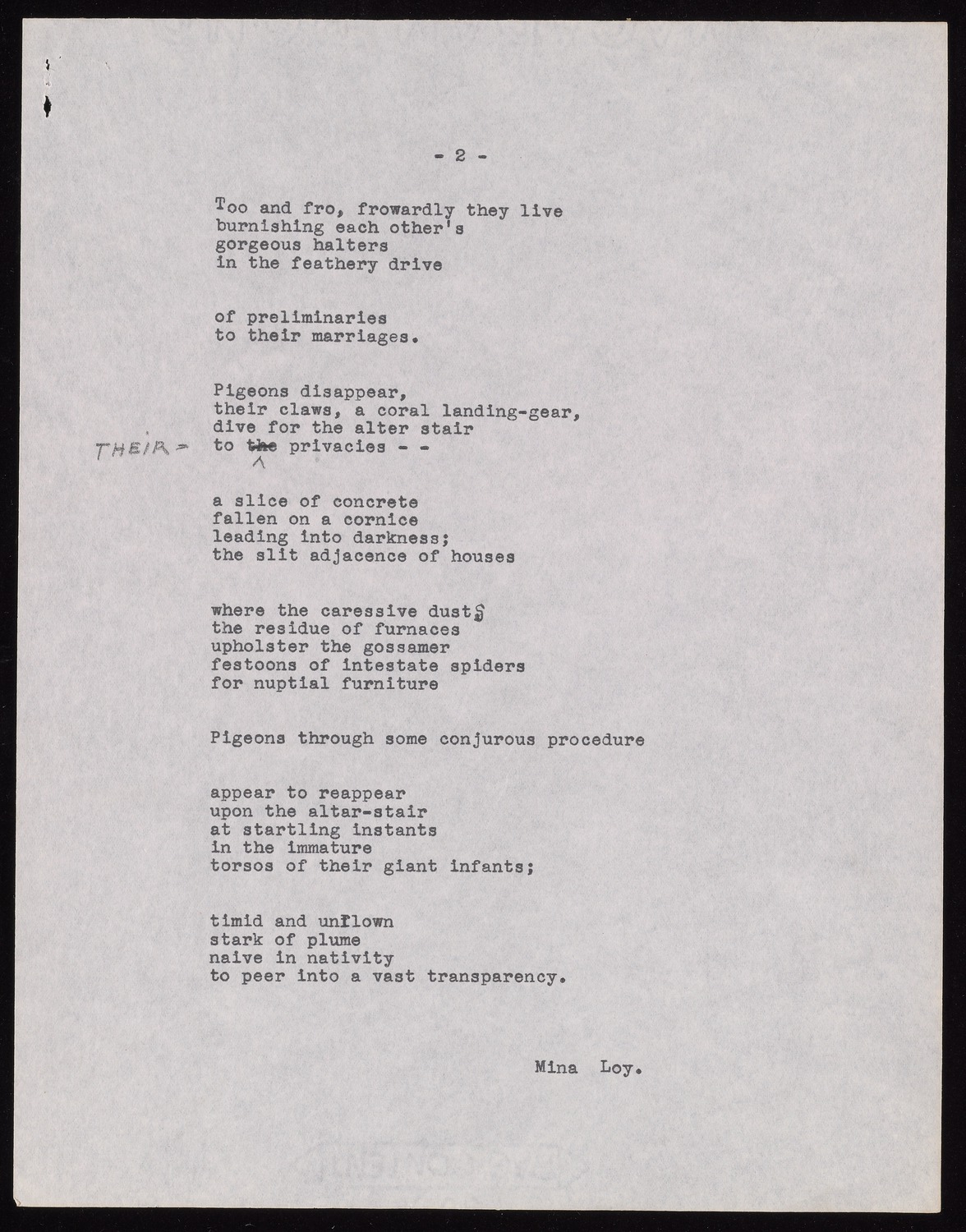

Loy also uses the diction of private property, domestic economy, and marriage — those pillars of life taken for granted by the middle class — to highlight how pigeons creatively survive in a public, human landscape largely devoid of nature:

Too and fro, frowardly they live

burnishing each other’s

gorgeous halters

in the feathery driveof preliminaries

to their marriagesPigeons disappear,

their claws, a coral landing-gear,

dive for the altar-stair

to their privaciesa slice of concrete

fallen on a cornice

leading into darkness;

the slit adjacence of houseswhere the careesive dusts,

the residue of furnaces

upholster the gossamer

festoons of intestate spiers

for nuptial furniture (LB96 121)

The allusions to marriage, altars, upholstery and nuptial furniture generate irony through the disparity between these middle-class foundations and the daily existence of pigeons, whose “property” is that margin of the urban landscape that is nominally public, where they are barely tolerated, yet in which they survive. The pigeons manage to create a “private” space out of the gap between human houses, which Loy gives visual as well as textual form in a box-like stanza:24

a slice of concrete

fallen on a cornice

leading into darkness;

the slit adjacence of houses (LB96 121)

Loy’s poem reveals to human observers the ingenuity of the pigeons who make do in the margins of human culture, transforming these forgotten places into the material of pigeon life, permitting the reproduction and survival of the species.

In describing this life cycle the speaker once again emphasizes the limits of what humans can see and know:

Pigeons through some conjurous procedure

appear to reappear

upon the altar-stair

at startling instants

in the immature

torsos of their giant infants;timid and unflown

stark of plume

naive in nativity

to peer into a vast transparency. (LB96 121)

As with other “inobvious” features of pigeon life, the appearance of large pigeon infants to the human observer seems “startling” or sudden, a species of “conjury” — inexplicable because unobserved.

The speaker’s close observation of the pigeons and what cannot be seen or known results in a new vision and understanding of the bird, one with spiritual connotations. “Nativity” connotes the birth of Jesus Christ, and can refer to the artistic representations of Christ’s birth. What kind of “nativity” has Loy presented with the baby pigeons? Jim Powell argues that “Loy’s pigeons are figures for the holy spirit” (16) and Carolyn Burke sees them as “the intertwining of body and soul” (417); both critics suggest that the poem alludes to the Sermon on the Mount: “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they?”

Maeera Shreiber argues that “Departing from that mystical tradition which endeavors to look into the secret life of things, Loy claims that all things have a life that remains necessarily secret” (474); she adds, “Loy’s visionary poems are located in the small spaces between what can and cannot be known” (475). Whether or not one sees the birds as figures for the spirit, through the pigeons Loy’s speaker seems to acquire an understanding of a new kind of vision. To peer means to look carefully or with difficulty, and Loy’s punning, rhyming language — disappear, appear to reappear, to peer, vast transparency (parents see) — positions the young pigeons’ sight as beyond the visual knowledge of the human speaker.

“Vast transparency” is an abstraction, an undemarcated space that is penetrable by vision (transparent), and connotes a kind of window (echoing the factory window at the start of the poem) but one that lacks an edifice: this abstraction points to the possibilities but also to the limits of human vision and knowledge, allowing one to imagine how or what the young birds might see as they first climb the stairs up to the city street, but also to confront the unknowability of this view. The speaker in an attempt to understand what the birds see, also “peers into a vast transparency.” Loy’s statement about Brancusi and Cornell — “The first is the purest abstraction I have ever seen; the latter the purest enticement of the abstract into the objective” — applies to the conclusion of her poem as well.

The bird has a long history as a figure for the lyric poem and poet, and we can chart the trajectory of the romantic to modern lyric through the changes in its iconic birds: from Keats’ nightingale to Baudelaire’s swan to Hardy’s thrush and Frost’s Oven Bird, Stevens’ blackbird, Bishop’s rooster, and Moore’s and Loy’s pigeons. In choosing the pigeon Loy shifts the location of the lyric from the heights down to the prosaic sidewalk, and like Baudelaire broadens the lyric to encompass the reality of urban life. But she keeps the origins of the lyric as song in mind: as Jim Powell notes, Loy pays attention to the pigeons’ “irritant, alluring / music” and the poem’s subtle use of rhyme and sound mimics the “cooing” of the pigeons (16).

The shift in perspective central to “Property of Pigeons” was also explored by Loy in her visual works from this era. For instance she takes up the perspective of the sidewalk in several assemblages featuring bums on the Bowery. One assemblage in particular (c. early 1950s) changes depending on one’s perspective. Loy depicts a bum under sidewalk pavement, his hands and head emerging from the pavement: if the work is placed on a tabletop and viewed horizontally, the bum would appear to be trapped beneath the concrete, or emerging from it like one of Loy’s incipient forms. However if the work is hung on a wall and viewed vertically, the bum appears to be hanging, a Christ-like figure (akin to the figure in Loy’s assemblage “Christ on a Clothesline”). Loy played with Surrealism’s “topsy-turvy” perspective in her 1930 painting Surreal Scene (depicting upside-down figures sitting on a ceiling) and in Insel; she commented in “Phenomenon” that “[Surrealism’s] theoretic contrivance for somersaulting reasons into an ‘Alicism’ world of topsy-turvy logic greatly entertained me [but] my conclusive reaction to much of it was ‘Black Magic’” (LB82 301).

In her late poems and assemblages Loy imbues Surrealist “topsy-turvy” shifts in perspective with ethical questioning and spiritual reflection, or what she termed “White Magic.” Viewed horizontally, is the bum trapped under the sidewalk equivalent to garbage to be trod on, imprisoned by his cement environment? Viewed vertically, does he become a kind of saint? Perhaps Loy uses the vertical presentation of the bum’s horizontal position (lying on the sidewalk) to invite viewers to see this figure with fresh eyes, much as she does with her pigeons. Shifting perspective may enable an ethical extension of perspective.

Loy’s protagonist Mrs. Jones comments on a similar play with perspective in Insel: “Again I received a strictly lateral invitation to wholly exist in a region imposing a supine inhabitance. A region whose architecture, being parallel to Paradise, is only visible to a horizontal gaze. Should one stand up to it, it must disappear.” “Supine” means lying face upward, or failing to act or protest as a result of moral weakness or indolence. The bum lying on the sidewalk, too easily dismissed as indolent, perhaps searches for or sees “Paradise.”

Pigeons in Flight: Cornell’s “Aviary” (1955) & “Nymphlight” (1957)

Cornell featured pigeons in two films he made with Rudy Burkhardt (a painter, photographer, experimental filmmaker): Aviary (1955) and Nymplight (1957).25 Like “Property of Pigeons” these films allow an altered perspective on the city and its human inhabitants to emerge through a focus on the pigeon’s habits and habitat. While Loy’s “Property of Pigeons” takes the city streets as its setting, Cornell and Burkhardt filmed “The Aviary” in Union Square Park and “Nymphlight” in Bryant Park (Solomon 227, 246).

Union Square Park is bordered on the south by 14th Street (also the subject of Loy’s poem “Mass Production on Fourteenth Street”), and city traffic, buildings and stores such as Klein’s and The Fair are visible as the backdrop to the park. Bryant Park backs up to the New York Public Library and is also surrounded by buildings, but is more removed from urban and commercial traffic. As Deborah Solomon states, “A formal square, it had statuary, pathways, and a majestic stone fountain where he [Cornell] often paused to admire the inevitable city pigeons” (247).

The juxtapositions and traffic between the parks and the city that surrounds them is central to the perspective and action of both films. Jed Perl points out that in “The Aviary” and “Nymphlight,” the parks “took on some of the quality of an enclosed dreamworld that you find in Cornell’s boxes” (296), while Deborah Solomon argues that Cornell “now tried to extend the theme of his [aviary] boxes into film; he turned the park into a virtual Cornell bird box, with the buildings around it serving as walls” (228). However, Cornell’s choice to supplant static box constructions with film, the box or bird cage with city parks, and tropical birds with pigeons, changes the meanings and possibilities of the aviary.

Both films depict the park as offering a pastoral oasis in a largely concrete city: to the pigeons the park offers trees, grass, water and shade, and to humans the park offers a break from traffic or a less trafficked cut-through, and a place to sit and rest, to play, and to engage with nature (trees, sky, water, pigeons). The method of filming is also unhurried, resisting the city’s rush, and the camera focuses equally on the pigeons and humans, often cutting between them to create meaningful juxtapositions and to suggest their similar uses of the park.

In “The Aviary” for instance, Cornell and Burkhardt created the following sequence of shots: a man on a bench reads a paper with pigeons around him, a dog sniffs its way through the park, a man slowly walks with a cane while reading a newspaper, a child runs on a path, a small dwarf walks towards the camera on a path, pigeons walk on the path, a man on a bench eating food tosses a piece to the pigeons, pigeons look for food on the ground, pigeons eat, rest, and clean themselves. In such sequences the film implies a subtle parallel between the pigeons’ natural needs and use of the park and those of the humans: food, rest, shelter. In an early sequence of a man feeding pigeons (3:56 – 5:00), one pigeon climbs on to the man’s arm from a fence rail and other pigeons eat from his hand, suggesting the literal co-dependence of pigeons and humans in the city.

Nymphlight creates similar connections between pigeons and humanity; in one sequence the camera is held right next to the tree trunk looking up into the branches, which are filled with pigeons. Looking up into the tree from this angle one has the sense of the tree as a crowded home, ringed by apartment buildings at the edge of the shot. This perspective on the tree as akin to an apartment building is confirmed when the camera cuts to a view of the street seen beyond the corner of the park: it it filled with cars, buses, and people walking.

As the parks support the avian and human life that come through them, so do their public monuments and statues, and Cornell explores this art-nature connection in both films. Parks can be understood as domesticated or artfully-designed nature, and both Union Square Park and Bryant Park contain public art in the form of fountains that take their inspiration from nature.

In “The Aviary” the fountain features a mother with children as a centerpiece, and around its base carved in relief, appear a number of creatures: a lion’s head with a spigot for water, a salamander, pigeons, a butterfly, a dragonfly.

The fountain in “The Aviary” lacks water (given the winter season) but depicts natural creatures, and presumably supports birds and other creatures when its water supply is turned on. In one shot the camera frames the mother/child fountain centerpiece with tree branches in the background in which birds are resting, suggesting a visual analogy between the maternal figure of the fountain and that of the tree. Humans also take succor from the public art: near the start of “The Aviary,” the film focuses on a woman examining the fountain, and later returns to her as she steps down from the fountain with a smile and walks toward the street. The camera tracks her walking on a sidewalk as seen through the park fence, presumably re-entering the city with renewed life.

Similarly, “Nymphlight” features a fountain that supports birds and human life; however, the season is summer so the fountain is full of water. The film begins with a young girl in a long white dress and parasol (the nymph) running through the park towards a fountain with pigeons.26 The camera shows the girl looking up at the pigeons as they fly into trees with the buildings in the background, and then switches focus to explore the small round fountain with running water. The film includes many close-up shots of the pigeons drinking from the fountain, bathing, and standing on the fountain’s edge. A number of people in the course of the film also enjoy the fountain — the nymph looks at it later in the film, a woman walks by it with her dog, and working men sit on the fountain’s edge to relax.

The final shot of Nymphlight focuses on a reflection in the water, of the fountain or a building: the camera holds this frame until a water drops hits the surface, causing it to tremble. As an analogy to the film surface and the natural movements film is able to capture, the water in the fountain self-reflexively figures the pastoral vision of “Nymphlight.”

“Nymphlight” emphasizes the importance of the pigeons towards the end of the film (6:42 – 8:00). The camera shows the young girl (nymph) looking at the fountain, and then focuses on another young girl, who looks at pigeons on the ground as men walk purposefully by her through the park. Neither the girls nor the pigeons follow a straight line, but pause and change direction. Pigeons in this way are aligned with the spirit of the nymph and filmmaker.

The camera then focuses on the pigeons looking for food (8:00 – 8:22), but takes up their close-to-the-ground perspective; as people walk by, the camera shows the humans’ truncated legs and feet, due to the ground-level focus on the pigeons. Here the film asks its viewers to take on the pigeon’s perspective of the park, much as Loy presents young pigeons on the sidewalk peering into a vast transparency at the conclusion of “Property of Pigeons.”

The film then cuts to a shot of a park worker with a wagon into which he empties trash cans (8:23 – 9:09). He walks by a metal trash can containing the nymph’s folded up (and curiously bird-like) parasol. This trash can resonates with the trash cans in Loy’s poems and constructions of this era (e.g. Hot Cross Bums), and suggests the containment of dreams and art within larger economies of meaning and value, and the park as a pastoral oasis contained within and permeated by the city that defines its edges. Nevertheless, as the film ends and we exit the film and park, we presumably carry the nymph’s pastoral spirit with us, out into the city. Offering viewers an altered vision of their everyday surroundings, “Aviary” and “Nymphlight,” like Loy’s “Property of Pigeons,” capture the ephemeral poetry of urban life.

- See Tim Armstrong’s essay “Loy and Cornell: Christian Science and the Destruction of the World” (Salt). Christian Science was a strong point of connection between Cornell and Loy, although Cornell was more faithful regarding daily and weekly readings in Science and Health. Cornell’s belief in Christian Science qualified his understanding of the unconscious. In a November 21, 1946 letter to Loy he wrote, “My Science and healthy thoughts about the unconscious in Surrealism (about which I knew nothing) combined to give me extraordinary emotions”; he added, “Maybe Breton has splendid visions but one doubts it from the way he holds his pipe” (Burke 405). Loy became interested in Joel Goldsmith’s The Infinite Way at this time; Goldsmith was born Jewish but turned to Christian Science, then streamlined its ideas (Burke 414-15). Loy wrote to Goldsmith and spoke with him by phone; Cornell apparently knew him, too, as his diaries record visits to Goldsmith.

- Ingrid Schaffner dates Cornell’s “Portrait of Mina Loy” box to 1936 (Portrait p. 136, Plate 43), as does Linda Kinnahan (Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography 34), while Burke dates it to 1933, after Cornell saw Loy’s painting exhibition at the Levy Gallery (407). Tara Prescott dates it to 1938, and includes a detailed description of the box (106-7).

- Although Loy and Cornell had likely met at the Levy Gallery prior to 1943, this moment lead to a new stage in their friendship.

- Joseph Cornell papers, 1804-1986, bulk 1939-1972. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- A copy of the November 21, 1946 letter from Cornell to Loy can be found in the Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 4, Folder Joseph Cornell.

- Joseph Cornell papers, 1804-1986, bulk 1939-1972. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 4, Joseph Cornell Folder.

- Cornell had thought to ask Marianne Moore rather than Loy for an appreciation of his Aviary show; Donald Windham wrote the appreciation that was published in the exhibition catalog. A shared interest in collage as well as spirit and grace connects Cornell and Moore, but also Cornell and Loy: both Moore and Loy functioned as Cornell’s poetic muses at this moment. Tellingly it was Loy not Moore whose “winged words” (Cornell) would best articulate the method, aims, and effects of Cornell’s Aviary. Loy drew Moore in 1928 on a visit to Joella and Julien Levy in New York, and as Carolyn Burke has discussed, these two poets and their careers were often compared by male critics (see Burke 221, 403). On Moore and Cornell, see Ellen Levy’s excellent discussion in Criminal Ingenuity.

- I quote from the version of the essay published in Last Lunar Baedeker (1982).

- See Ashley Lazevnick, “Impossible descriptions in Mina Loy and Constantin Brancusi’s Golden Bird.”

- The recent exhibition of Cornell’s boxes for/inspired by Juan Gris (Birds of a Feather: Joseph Cornell’s Homage to Juan Gris) bear out Loy’s astute analysis.

- See Loy’s “Gate Crashers of Olympus” (SE, 230-1), on Braque and Picasso or as Loy puns, “P.O. Casse (cf. French breakage).”

- Walter Benjamin elucidates the importance of the apprehension of evil to the Surrealists: in keeping with the Surrealist efforts to challenge middle class idealistic morality, “One finds the cult of evil as a political device, however romantic, to disinfect and isolate against all moralizing dilettantism” (Reflections 187). Evil is closely tied to the Surrealist belief in an absolute freedom, including freedom from organized religion and bourgeois morality. (LLB82 300-301)

- Cornell wrote to Alfred Barr in Fall 1936 as Barr was preparing the catalog for the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition that “I would appreciate your saying that I do not share in the subconscious and dream theories of the Surrealists. While fervently admiring much of their work I have never been an official Surrealist, and I believe that Surrealism has healthier possibilities than have been developed. The constructions of Marcel Duchamp who the surrealists themselves acknowledge bear this out, I believe” (Solomon 84). Cornell similarly wrote to Charles Henri Ford in 1939 of his “total lack of interest in psycho-analysis and the current preoccupation with sex” (Solomon 95).

- Tim Amstrong questions Loy’s paradoxical interest in embodiment and in Christian Science, “a religion which dismisses mere physical existence” (Salt 206), arguing that “one answer to the question involves seeing that Christian Science does not so much abolish the object as replace it with something different: a transfigured reality” (Salt 206). Armstrong emphasizes that Christian Science and Surrealism share “the abolition of the world in favour of a transfigured reality, a universe of desire” (Salt 210-211). Maeera Schreiber similarly argues that Loy’s late poems find that “holiness is necessarily a broken thing — to be found in the bodies and in the faces of society’s outcasts, otherwise known to her as ‘angel bums” (468). Shreiber argues that Loy’s interest in the sexual body in her late work “may be understood as an interpretation of Christian Science’s view of the spiritual value of the physical” (469).

- For Loy both the bird and the aviary were long-standing subjects that preceded her friendship with Cornell. Loy’s unpublished, autobiographical manuscript The Child and the Parent begins “with the metaphor of a bird alighting as a symbol of the soul’s appearance in the world” (Burke 354), and contains a chapter titled “Ladies in an Aviary” that depicts Victorian women as birds trapped in their cages. Loy wrote her long poem about Isadora Duncan at least two years after seeing Cornell’s Aviary show at the Egan Gallery. Loy’s reflection on Duncan as a modernist woman artist who defied social and artistic conventions invites comparison with Cornell’s use of female opera singers and ballet dancers as muses. Both Deborah Solomon and Ellen Levy offer astute analyses of gender and erotic desire in Cornell’s boxes.

- In his Aviary box for the opera singer Guiditta Pasta, Cornell associates the singer with a white parrot. Many of his Aviary boxes from the late 1940s contain music or music boxes; Lévêque-Claudet writes, “In ‘Untitled (Cockatoo and Corks) c. 1948 […] the system of including a music box, which is visible in this case, serves at the same time as a decorative motif and as a way to play the music” (145).

- This aesthetic of surprise is indebted to Apollinaire, “L’Esprit Nouveau et let poètes,” a foundational document for the Surrealists.

- Ekphrasis is described by James Heffernan as a “verbal representation of a visual representation” (Museum of Words 2).

- The essay (from essayer, to try, to experiment) is similar in style to Cocteau’s “Laic Mystery” on De Chirico’s paintings, to Apollinaire on Picasso’s paintings, and to many of the essays by surrealist poets on surrealist painting published in little magazines in the 1920s (Rosenbaum, “Exquisite Corpse”).

- Neiman published Impossible Opus, Photo After Pogrom, Negro Dancer, and Property of Pigeons in the Spring/Summer 1961 issue of Between Worlds; he published Faun Fare and In Extremis (“Show me a Saint Who Suffered”) in Fall/Winter 1962. Ephemerid, Hilarious Israel, Aid of the Madonna, and Chiffon Velours were published in Accent in the 1940s; Hot Cross Bum was published in New Directions in 1950; and Idiot Child on a Fire-Escape was published in Partisan Review in 1952. Deirdre Egan has argued that Loy’s drafts that list poems from this era under the title “Compensations of Poverty” indicate her conception of these poems as a carefully-arranged sequence “that is interrelated as other modern longs poems are” (970, 985).

- Jim Powell argues that Loy’s concern is to bring the pigeon’s nature into the poem, and only “by implication the life of their observer […] as an instance of a common urban humanity and fate realizing itself in the terms and gestures of a companionable portrait of these creatures with whom it shares the city” (16).

- This theme is resonant with Cornell’s Aviary boxes (Abandoned Perch, Abandoned Cage) which lack a bird, prompting the viewer to wonder what has caused the bird’s absence.

- Although Cornell’s boxes purport to capture and display exotic birds rather than pigeons, they too emphasize the mysteries of avian life through their stacks of small drawers, whose contents are blocked from the viewers’ eyes.

- Cornell would collaborate on nine films with Rudy Burkhardt. They filmed “The Aviary” in November and December 1955 over three Sundays; as Burkhardt filmed Cornell directed where to film (Solomon 228).

- The “nymph” was played by Gwen Thomas, a student at the School of American Ballet, and the film focuses on her “interaction with the pigeons,” suggesting that both are “flight-bound nymphs” (Solomon 247).