In this section you can explore:

- Paris Agent for the Levy Gallery

- The Julien Levy Gallery

- Insel as Textual Gallery

- A Gallery of the Increate

- Mina Loy’s 1933 Exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery & her unexhibited 1930s Paintings

Paris Agent for the Levy Gallery

In 1931 Loy began to serve as the Paris agent for the innovative Julien Levy Gallery (1931-1949), which not only held the first Surrealist exhibition in New York in January 1932, but throughout the 1930s and 1940s served as the premier American gallery for Surrealist work of all kinds.1

The story of how this came to pass involves the trans-Atlantic circuit of art and artists that characterized Loy’s career.

Duchamp — like Loy, a pivotal figure in the trans-Atlantic migration of Surrealism — played a key role in introducing Loy to Julien Levy. Duchamp met Julien Levy in New York when Duchamp learned that Levy’s father Edgar had purchased Brancusi’s Bird in Space. Loy’s poem “Brancusi’s Golden Bird,” originally published in The Dial 73 (November 1922) and republished in Lunar Baedecker (1923), had accompanied the 1926 exhibition of Bird in Space at the Brummer Gallery in New York (Januzzi, “Bibliography” 523). With Duchamp and Robert McAlmon, Julien Levy traveled to Paris in February 1927, where he met Mina Loy and her daughter Joella at a party at Peggy Guggenheim’s. Levy married Joella in August 1927 and remained entranced by his mother-in-law’s beauty and artistic gifts; he would help to promote Loy’s poetry and visual art through the remainder of her career (Burke 346, Burke “Loy-alism” 62). With Julien and Edgar Levy’s financial help, Loy was able to buy out Peggy Guggenheim’s share of her lampshade shop in 1928, and then to sell it in 1930, permitting more time for her writing and art. Levy opened his New York gallery in November 1931 and arranged for Loy to become his Paris representative, which “justified the monthly ‘allowance'” that he sent to her (Burke 377).

As the agent in Paris who arranged the purchase and transportation of Surrealist art to Levy’s Gallery from 1931-36, Mina Loy was a central figure in European Surrealism’s trans-Atlantic career and reception in the United States. In Paris, Loy negotiated acquisitions with the Bermans, Giacometti, Tchelitchew, De Chirico, and Massimo Campigli, and commissioned work from Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, and Magritte; she also worked with Pierre Colle and Leonce Rosenberg who had galleries showing Surrealist work in Paris. After viewing Luis Buñuel’s L’Age d’Ôr in 1932 with Julien Levy and Lee Miller, Loy encouraged and helped to arrange the film’s premiere in New York (Burke 378-9; Schaffner, “Alchemy” 37). Loy’s dealings with the German surrealist painter Richard Oelze in 1935-6 would inspire her novel Insel, which chronicles the relationship between Mrs. Jones, a character based on Loy’s role as Levy’s Paris agent, and Insel, based on Oelze. In the novel (discussed in detail below), Loy reflects on her role as Levy’s agent as well as her own aspirations as a writer and painter engaging Surrealism.

The statement “I’m not the Museum” appears in Loy’s novel Insel. After angering Insel by offering pointed, feminist commentary on his painting Die Irma intended for the Levy Gallery, Mrs. Jones quips “What does my opinion matter? I’m not the museum” (133), distinguishing her perspective and power from that of the gallery-museum network she served.

“I’m not the museum” reflected a broader transformation of the museum by the avant-garde. Taking the “museum as muse,” European Surrealists and their admirers creatively defied the official museum’s rational, didactic aims by reimagining it, creating galleries and collections that transformed the museum into a stage for Surrealist-inspired ends, including the fusion of dream and reality, disorienting perspectives on the real, urban wandering, the pursuit of pleasure and desire, and the merging of art with everyday life (Rosenbaum, Brides; Kachur, Displaying). They regarded the museum not simply as a physical space for exhibition, but also considered it as an arbiter of cultural value, a repository of cultural memory, a script for viewing modern art, an epistemology, and a malleable, hybrid form of collection and display that could include, for instance, the exhibition catalogue, the little magazine, the poetic collection, the private living space, and the gallery-based film or performance (Rosenbaum, Brides). Thus while their museums took concrete form, they were “imaginary” and at times “without walls” in their play with and transformations of the scale, materials, and aims of the museum collection, and in their efforts to engage the spectator’s imagination (Malraux).

More pointedly, women such as Mina Loy used their position on the margins of both the museum and the avant-garde as an impetus to reimagine both, and in doing so, to comment variously on institutional power, the practices of Surrealist display, and gendered modes of looking.

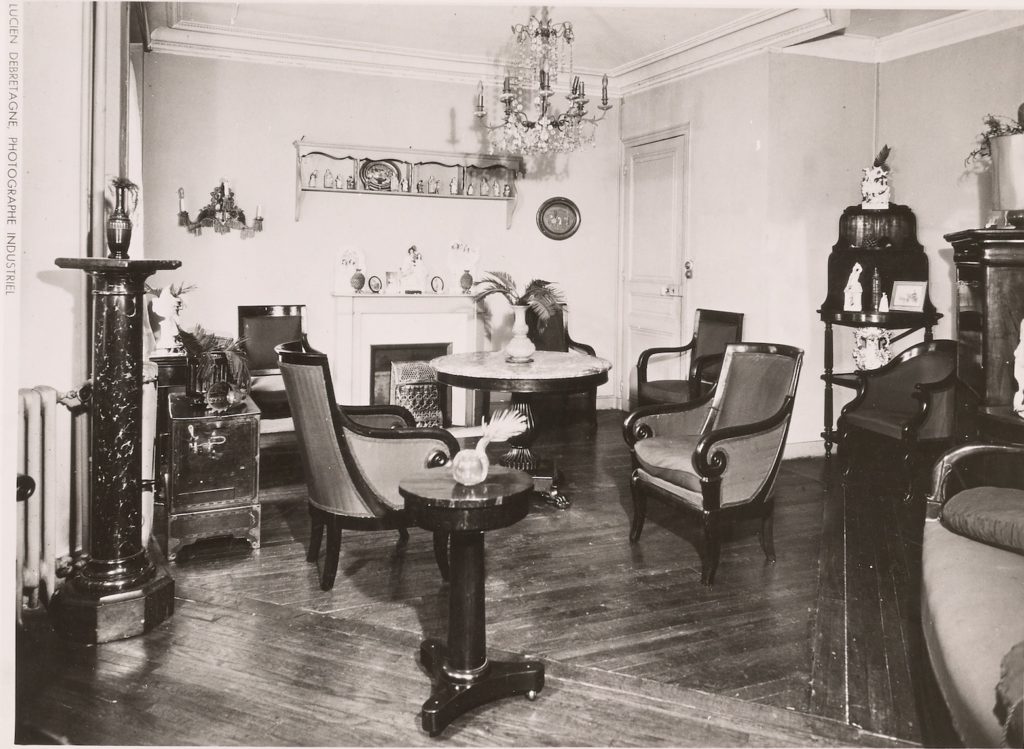

For Loy, alternative spaces of exhibition included her apartment, her lamp shop, the Levy Gallery, the canvas of her painting Surreal Scene, and the pages of her novel Insel. These exhibition spaces were shaped by Loy’s need to make a living, and by her melding of her role as artist-poet with her roles as gallery agent, shopkeeper, designer, and inventor. Loy approached her 9 Rue St.-Romain apartment (where she lived with her daughter Fabienne from 1929 to 1936) as a space of creation and display, both studio and self-curated gallery: she painted many of her Surrealist-influenced works of the early 1930s there, including Surreal Scene (1930), wrote poems and essays, and began writing Insel. In this apartment Loy also read drafts of Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood which likely influenced Insel (Burke 368).

Carolyn Burke suggests that Loy’s lampshade shop and her 9 Rue St.-Romain apartment influenced the “artistic spirit” of Levy’s Gallery (“Loy-alism” 67). Burke describes Loy’s apartment thus:

A poetic melange of flea market finds, decorative schemes devised to hide flaws, and idiosyncratic art gallery composed of Mina’s paintings, Fabi’s drawings, and photographs of Cravan, it also featured Mina’s collection of antique bottles, Fabi’s bird cages as room dividers, and silver paper in floral patterns pasted over cracks in the plaster. (“Loy-alism” 67)

Carolyn Burke also remarks that “[Joseph] Cornell kept in his files, possibly for future use, a photograph of the mantelpiece in Mina’s Rue St.-Romain apartment labeled ‘Paris, 1920s.’ It showed, in evocative juxtaposition, an owl statue, a harlequin figure, several old-fashioned toys, a figurine in a long robe, and a tiny Madonna in a bird cage” (407). This photo has been preserved in Cornell’s papers in the Archives of American Art:

Loy had clearly transformed a mantelpiece in her apartment into a small installation that anticipated the juxtaposition of objects in Cornell’s boxes (see “Sidewalk Surrealism”). Loy’s careful arrangement of objects is also evident in the photo of her 9 Rue St. Romain apartment sitting room (above), and in the lists she maintained of her bottle collection, which indicate the location in her apartment of every bottle.2

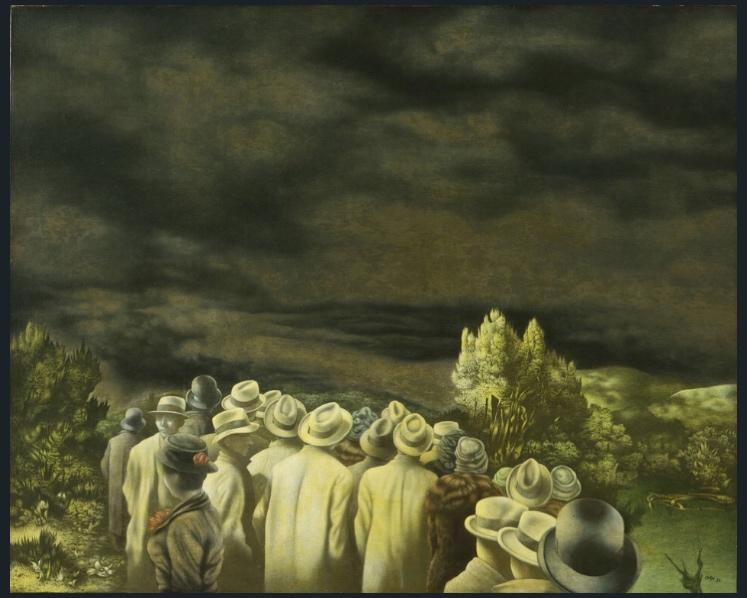

Loy’s Paris apartment also served as a transient gallery for works awaiting shipment to New York. In Summer 1931 Levy bought Dali’s The Persistence of Memory and stored it in Loy’s apartment prior to exporting it to his Gallery; the painting was shown in the Levy Gallery’s inaugural January 1932 Surrealism exhibition and “stole the show” (Burke “Loy-alism” 69). Oelze’s painting Expectation (1935-1936) also hung in this space before transport to Levy’s Gallery in Fall 1936 and MoMA’s permanent collection in 1940 (Burke 385, Burke “Loy-alism” 72). Levy included both The Persistence of Memory and Expectation in his book Surrealism (Black Sun Press, 1936, Plates 52 and 58).

Levy described the apartment’s design as “by Loy out of the Marché aux Puces” (“Loy-alism” 69), romanticising what for Loy had been less a choice than making a “virtue of necessity” (Loy-alism 69). Levy also admired Loy’s lampshade shop, which doubled as a Gallery (for Laurence Vail’s paintings in 1927), and in his own Gallery he would sell books, magazines, and “his own photo objects, trompe-l’oeil wastebaskets and lampshades” (Schaffner, “Alchemy” 23).

The Julien Levy Gallery

Although the Museum of Modern Art’s 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition brought Surrealism to wide public prominence in the U.S., Levy’s Gallery had provided the blueprint and some of the art for the exhibition.3 James Thrall Soby said that Levy “was as close to being an official Surrealist himself as one could come without signing one of André Breton’s guidelines to the Surrealist faith” (Schaffner, “Alchemy” 23).

Levy’s book Surrealism (published in 1936 by Caresse Crosby’s Black Sun Press) is a textual exhibition of Surrealism that illuminates the aims of his gallery. While Breton’s influence is clear, Levy’s book demonstrates his American adaptation of Surrealism, underscored by the cover, a Joseph Cornell collage of a small boy trumpeting the word “Surrealism,” shown in the gallery’s 1932 Surrealist exhibition.4

In contrast to Breton, Levy avoided defining Surrealism as a movement, emphasizing that “unlike so many other ‘isms’ surrealism is evidently not a deadend, it is not static, but is a dynamic and expansive point of view. Just as surrealism could invite the genius of Picasso so it may still invite the new generation of poets and painters” (Surrealism 27).

In its innovative layout (the gallery had curved white walls), its inclusion of books and periodicals, and its exhibitions of painting, film, photography, ballet, cartoons, and theater, Levy’s gallery had much in common with Surrealist-curated galleries and exhibitions (Schaffner, “Alchemy” 21, 33). As Ingrid Schaffner notes, “Pictures hanging on those walls took on a cinematic sequencing, directed by the dealer” (“Alchemy” 21).

Levy’s innovative approach to exhibitions shaped his plans with Woodner Silverman for a Surrealist House for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, inspired by the 1938 Surrealist exhibition in Paris (Kachur, Displaying 106). Subsequently, this house would become Salvador Dali’s Dream of Venus Pavilion, which incorporated the commercial and carnival elements of the fair (Kachur, Displaying 111-129).5

Levy screened films at his gallery by Buñuel and Dali, Léger, Disney, Cocteau, Duchamp, Man Ray and Joseph Cornell.6 As Linda Kinnahan discusses at length in Mina Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography, and Contemporary Women Poets, Levy began his Gallery to exhibit the work of Atget and other photographers, and the Gallery would maintain its focus on this art, sponsoring many solo exhibitions (including George Platt Lynes, Walker Evans, Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Lee Miller, and John Clarence Laughlin).7

Also notable were the number of women artists and photographers who received solo exhibitions at the Levy Gallery, particularly in comparison to other galleries and museums of this era: Levy mounted solo exhibitions by Lee Miller, Berenice Abbott, Mina Loy, Katherine Dreier, Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo, and Dorothea Tanning, among others.8 The gallery was as much a salon as an exhibition space, where European and American artists trafficked. For instance, Dorothea Tanning recalls an evening at the Gallery devoted to seven chess games played in sequence. As Philip Johnson commented “We give credit to [Levy] for establishing a home for Surrealism in America” (Schaffner and Jacobs, “Reminiscences” Portrait 172).

Levy’s American adaptation of Surrealism would set the stage for other innovative galleries and little magazine publications such as Charles Henri Ford’s View in the U.S. (Rosenbaum, “Exquisite Corpse” 281-7). As a point of comparison with Levy’s Gallery, in 1937 Breton opened the Gradiva Gallery in Paris (Chadwick 50). This gallery was located on the Rue de Seine, with glass doors designed by Marcel Duchamp, figuring a conjoined man and woman. Freud’s analysis of Jensen’s novel Gradiva was “a significant Surrealist guide during the 1930s” and inspired the name of the gallery (Chadwick 54-5).

Mina Loy’s Insel as textual gallery

The novel Insel is loosely based on Loy’s role as agent for the Levy Gallery and chronicles her relationship to German surrealist painter Richard Oelze.9 On Julien Levy’s instructions Loy contacted Oelze who had lived in Paris since 1933; Levy told Loy to “draw him out, offer moral and financial support, and select those canvases that seemed suited to America” (Burke “Loy-Alism” 73). Oelze was isolated and poor, and Carolyn Burke writes that “few outside the Surrealist inner circle — Breton, Dali, and Oelze’s compatriot Max Ernst — knew much about him” (Burke 381). Elizabeth Arnold postulates that “it may have been this shared aversion to wholehearted membership in groups that drew Loy and Oelze together” (“Afterword” Insel 183).10 Loy’s protagonist Mrs. Jones sees Insel (based on Oelze) as “too surrealistic for the surrealists” (125), and notes Insel’s “distinction” as someone who like herself “‘popped up’ from nowhere at all – as if all my life I had lacked a crony of my ‘own class'” (59). Loy’s ability to speak German and a shared affinity for an art of “incipient forms” sealed her friendship with Oelze.

As discussed above, Loy’s Paris apartment often served as a transient gallery for works awaiting shipment to New York, including Oelze’s painting Expectation (1935-1936) (Burke 385, Burke “Loy-alism” 72). Carolyn Burke comments on Expectation‘s ominous mood: “it is impossible not to see in the work the years of its composition, 1935-1936, and in the mute backs of its Magritte-like subjects bourgeois refugees already on their way to the death camps” (“Loy-alism” 74). Loy’s Mrs. Jones describes a very similar painting of “a gigantic back of a commonplace woman looking at the sky,” adding, “It’s here to be shipped with the consignment I am sending to Aaron, and I swear whenever I’m in the room with it I catch myself staring at that sky waiting, oblivious of time, for whatever is about to appear in it” (Insel 20-21).

While Loy’s apartment served as both her studio and ephemeral gallery space, in Insel Loy created an experimental text-based “gallery” at once inspired by and critical of Oelze and his paintings. The novel also served as a space in which Loy tested out her ideas about her own Surrealist paintings and designs from this era (discussed below). Several scenes from the novel take place in Mrs. Jones’ Paris apartment, which resembles Loy’s, suggesting how Loy’s writing helped to transform her 9 Rue St. Romain apartment from a studio-gallery into an “irreal” textual gallery, a space as much psychological and imaginary as visible and real.

The novel is both a framing of Surrealist art and an “x-ray” of Oelze/Insel as a Surrealist muse.11 In Insel Loy animates the scene of Surrealist art’s reception by a female spectator to create a critical, feminist twist on Surrealist exhibitionary practices.

More pointedly, Loy’s treatment of her fictional protagonist Mrs. Jones, based on her own experience as Levy’s agent, allowed her to explore the difficulty of being slotted into the category of spectator, collector, or “patroness” rather than painter or writer, and to subtly merge these often-oppositional roles. Like Loy, Mrs. Jones is an artist and writer who arranges not only to serve as the artist’s agent, but also to write his biography (32). She meets Insel on the “unexplored frontiers of consciousness” (159) and finds him to be a “congenital surrealist” who “had no need to portray. His pictures grew, out of him, seeding through the interatomic spaces in his digital substance to urge tenacious roots into a plane surface” (103). Insel possesses a “conjurative power of projecting images” (53) but Jones learns that “he suffered . . . from the incredible handicap of only being able to mature in the imagination of another. His empty obsession somehow taking form in obsessing the furnished mind of a spectator” (156). Mrs. Jones must also supply the literal furnishings for Insel’s art: while she sometimes feels that Insel “has found a short cut to consummation in defiance of the concrete. That he is filling the galleries of the increate” (125), at other times she sees him in her role as gallery agent as a blocked artist whom she must urge to finish work for New York. In Mrs. Jones words, her job is “feeding a cagey genius in the hope of production” (74).

To elicit that production, she allows the destitute Insel to stay in her apartment, and undertakes housework that distracts her from her own art. She comments that, “the effort to concentrate on something in which one takes no interest . . . is the major degradation of women” (39). In preparation for Insel’s stay, Jones stuffs her own “scribbles” into a “corpse-like sack” which she locks in a room (40), an allusion to Man Ray’s Enigma of Isidore Ducasse (1920), a sewing machine wrapped and tied up in an army blanket. Loy transforms Man Ray’s homage to Lautreamont’s famous description of beauty as “the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella” through the gendered economic realities that shaped women’s engagement with Surrealism: Mrs. Jones sews to support herself, and in this instance stitches her own art into a sack to make room for Insel’s.

As a collector and spectator of Insel’s projected images, Mrs. Jones not only allows Insel to “mature in [her] imagination,” but in writing down her diverse encounters with him and his art, creates her own visionary gallery of Surrealism, rendering spectatorship an artistic, transformative, and feminist act. Key scenes in the novel that involve the framing and display of Insel include: Mrs. Jones’s transformation of her apartment into a Surrealist installation featuring Insel as a sleeping sea creature; Mrs. Jones’s critical response to Insel’s painting Die Irma; and Mrs. Jones’s use of analogies to Surrealist film and photography to “develop” her images of Insel as they stroll around Paris.

Loy’s writerly techniques in these scenes allude to and draw on Surrealist art in varied media, including photographic superimposition (38-9, 63, 117), the Surrealist object (44-5), Surrealist film (51, 61-2, 84), and Surrealist painting (50-1). At times Loy adopts Oelze’s artistic method — one of shading in “invisible myriads […] so passionately with the overfine point of his pencil” (109) — to describe Insel and his art, as if to beat Oelze at his own game. Insel himself seems to embody the Surrealist image: Mrs. Jones comments, “He was so at variance with himself, he existed on either side of a paradox” (34); “He possessed some mental conjury enabling him to infuse an actual detail with the magical contrariness surrealism merely portrays” (51-2).

Loy often employs popular, commercial contexts of display in her portrayals of Insel as a means of undercutting his spiritual, ascetic pretensions: Mrs. Jones describes Insel as an exhibit in a wax museum, as the walking dead star of a horror film, as an actor “playing” Kafka to eke out his meager living, and as a Broadway showman. As the novel unfolds, Jones rather than Insel proves to be the master of Surrealism’s “magical” techniques in her descriptions of Insel and Paris, even as she skeptically debunks his “black magic” as showmanship, trickery, and the possible effect of morphine addiction.12 Thus the novel offers itself as a hybrid exhibition, one that draws on Oelze’s Surrealist ideals and techniques while subjecting them to feminist critique, gothic humor, and an American popular culture keen for Dali-style “extravagant publicities” (27).

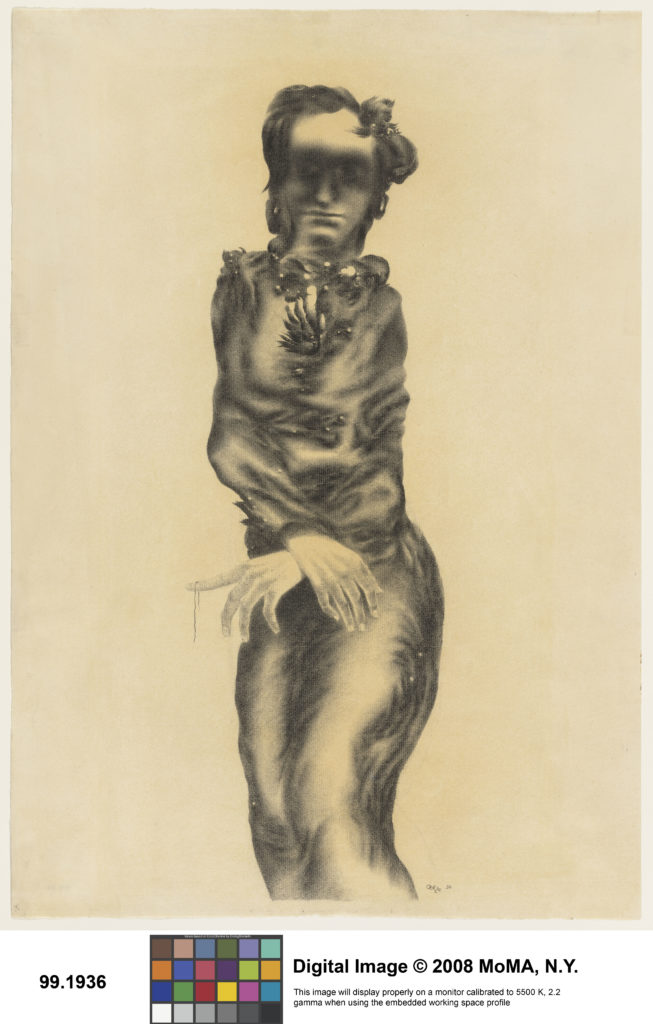

Mrs. Jones’s visit to Insel’s studio exemplifies Loy’s critical framing of Surrealism’s depictions of women. Insel shows Jones his painting Die Irma, which resembles Oelze’s Frieda, a work inspired by a character in Kafka’s unfinished novel The Castle.13 Mrs. Jones implies that Die Irma is Insel: her eyes are “flat disks of smoked mirror” that reflect her “creator” (131), and she has “male hands that hardly made a pair” (132). Mrs. Jones records the scene thus:

“Die Irma,” he repeated lovingly to introduce her to me, and the magnetic bond uniting her painted body to his emaciated stature – as if she were of an ectoplasm proceeding from him – was so apparent one felt as if one were surprising an insane liaison at almost too intimate a moment. (131)

Mrs. Jones raises up the sexual subtext to Insel’s painting when she observes, “He hung over Die Irma like a tall insect and outside the window in the rotten rose of an asphyxiated sunset the skeleton phallus of the Eiffel Tower reared in the distance as slim as himself” (132). Creating her own surrealist painting in this description, Mrs. Jones reveals the phallic aggression expressed by Insel towards his female muse and echoed by the culture through its revered symbols. Mrs. Jones objects to Insel’s use of the female form as a thinly-veiled medium for his own narcissistic preoccupations; Die Irma is mere “material” for Insel’s self-expression, the “bride” a projection of the “bachelor,” just as Insel feeds parasitically off of female prostitutes and patrons. She comments, “You have formed her of pus. Her body has already melted” and adds “I don’t care for it” (132-33). As Insel grows angry and threatens to destroy the painting, she quips ironically, “What does my opinion matter? I’m not the museum” (133).

By articulating the sexual subtext of Insel’s portrait, Mrs. Jones refuses Irma’s role as a silent, pliable female muse. This refusal is echoed in the plot when Mrs. Jones objects to Oelze’s exploitation of black prostitutes (88-90), and criticizes his “maniac sadism” expressed in the “pounding tread of the infuriated male” (136). As Mrs. Jones refuses the role of muse or “bride,” Insel behaves like an “alienated husband” (167) and tries to strangle her, to force her to play the part he has assigned her — to “give in–obsessed by my beauty–having no hope–endlessly resigned” (158). Insel is impotent as both a man and artist, Mrs. Jones implies, and thus vampirically draws his power from the female form; when Insel comments that “Die Irma is wet,” implying that he has just finished the painting, Mrs. Jones fully intends the double meaning in her reply: “She isn’t, she’s bone dry, I felt her” (133-34).

Elizabeth Arnold proposes that Insel “can be read not only as an experiment in surrealist narrative, but as a satire on the whole surrealist endeavor,” with Breton’s Nadja in its sights (“Afterword,” Insel 186). She argues that “Loy may have actually structured her novel after Breton’s in order to satirize him — as Victorian-styled middle class voyeur –and to express her indignation at the compromised role the Surrealists assigned to women” (186). Loy reverses Nadja‘s plot, with Insel serving as male muse for Mrs. Jones’s “willful descent into a forbidden psychology” (Arnold 99; see also Miller, Bronstein).

A Gallery of the Increate

Oelze claimed in a letter to Alfred Barr, Director of MoMA, that he had destroyed the painting Frieda, but a charcoal sketch (1936) (see image above) – likely mailed by Loy – was included in Barr’s 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition, along with Oelze’s painting Daily Torments (1934).14 Burke notes that when Oelze moved to Switzerland in October 1936, his paintings were shipped to Julien Levy; he returned to Germany in 1938 where he served in the war, was imprisoned, and released in 1945 (“Loy-Alism” 74, 79). The Oelze works that were exhibited as part of the 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition, an exhibition crucial to the history of Surrealism in the U.S., remain in the Museum of Modern Art collection.

In contrast, despite attempts to interest James Laughlin in publishing Insel in 1938 and again in the 1950s and early 60s, Loy’s novel would remain unpublished until Elizabeth Arnold’s 1991 edition.15 Loy was until recently effectively erased from the history of Surrealism. Yet the novel transforms Mrs. Jones’s “I’m not the museum” into a badge of honor, a sign of her creation of independent avant-garde work– shaped by progressive attitudes on feminism, gender, and sexuality — that critically absorbs but is not obligated to Surrealism. Economically bound to the role of agent and spectator, Jones merges these roles with those of creator and curator of her own textual collection.16 Loy comments on the novel’s curatorial composition through Mrs. Jones: although Mrs. Jones risked a paralyzing “disintegration” and “dematerialization” akin to that of Insel (150-51), by the novel’s end she “had reached the stage . . . for creation, when all that one has collected rolls out with the facility of the song of a bird” (177, italics mine). In contrast, Insel remains blocked and fragmented, and risks remaining uncollected: in her visit to Insel’s studio to see Die Irma, Mrs. Jones advises Insel to “pull yourself together . . . you’ve got to finish this for the museum” (134).

In light of history, the novel’s ending might strike us as rich in irony; after all, Oelze’s paintings were exhibited in the 1937 Surrealism show and are housed in MoMA’s permanent collection, while Loy’s paintings from this time are largely unknown, and Insel remained unpublished until 1991 . Yet ultimately Loy, not Oelze, presents us with a gallery of the “increate” (125), which in its very marginality to the Surrealist movement and to the gallery-museum network Loy served, makes the claim that avant-garde ideals were most powerfully realized on these “en dehors garde” margins, in “museums without walls.” As Elizabeth Arnold states, “Loy uses Insel to set herself not just apart from but far above the Surrealists while at the same time guarding against this quintessential Surrealist’s instability and misogyny” (“Afterword” Insel 186).

Yet the “ending” of the novel has taken a further, fascinating turn, in keeping with what Sarah Hayden calls Loy’s “unrooted, unending Surrealism” (ISSS). In studying the drafts of Insel at the Beinecke Library, Hayden came across a text titled “End of Book Visitation of Insel,” which is “materially congruent in terms of paper, writing materials and handwriting with the holograph fragments which constitute the novel’s early draft notes” (“Introduction” xix). While the published text of Insel contains Loy’s chosen ending as it is drawn from “Loy’s last edited and corrected draft of the text” (“Introduction” xix-xx), this alternate ending invites new questions about the novel, and about Loy’s shift in perspective on Insel and Surrealism triggered by her move to New York.17

In the “Visitation” Mrs. Jones imagines Insel appearing as a spectral, surrealist apparition in her New York apartment (xxi), even as the actual Insel remained in Switzerland (xxvii). Hayden argues that “the ‘Visitation’ text figures the surrealist as a transtemporal, bilocating entity. Her ‘Sur-Realist Being’ stretches across time: existing at once in the deep past, the future and everywhere (or when) in between. […] His significance, as exemplar of a surrealism that transcends its location and moment, remains unexplored” (ISSS).

Mina Loy’s 1933 Exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery & her unexhibited 1930s Paintings

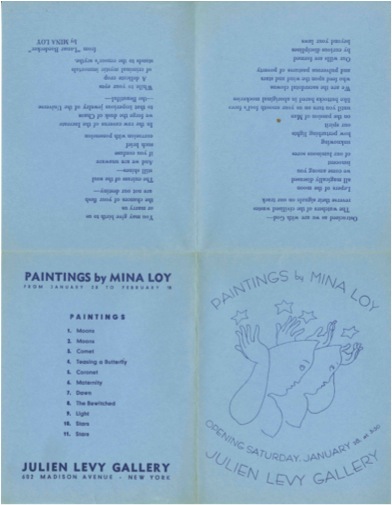

Mina Loy not only worked as an agent for the Levy Gallery, but exhibited her paintings at the gallery in January-February 1933 (a solo show) and in 1937 (a group exhibition). The catalog for the 1933 exhibition lists titles of the paintings prefaced by Loy’s poem “Apology of Genius.”

In many of these paintings Loy explored the celestial subjects of “Lunar Baedeker”: Moons, Comet, Dawn, Light, Stars.

A number depict hybrid creatures — snails with human faces, angel heads with wings — what Carolyn Burke calls “primordial shapes in the act of becoming” on a “blue-gray base of mixed sand, gesso, and plaster [Loy] called ‘fresco vero'” (Loy-alism 70-71).18 The contemporary reviews of Loy’s 1933 exhibition compared her paintings to the poetic paintings of Blake, Apollinaire, Eluard and Cocteau. Not coincidentally, Loy’s painting Faces was shown in 1933 at the Hartford Atheneum in their “Exhibition of Literature & Poetry in Painting Since 1850.”19

Photos taken by Maurice Poplin housed with Loy’s papers at the Beinecke Library (labeled “Julien Levy Gallery 1933”), also document a sequence of sixteen paintings, carefully numbered and titled by Loy.

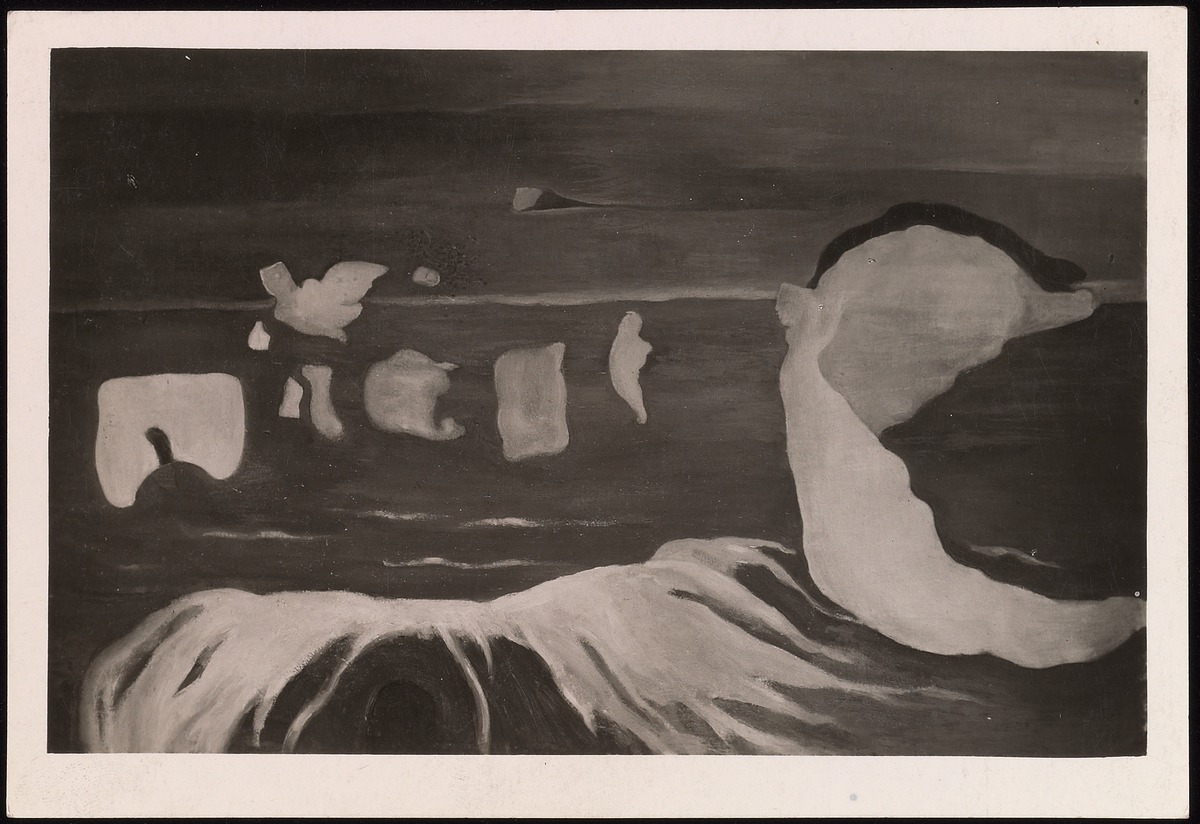

Drift of Chaos

I Drift of Chaos

II Drift of Chaos – Hermes

[no III in folder]

IV Drift of Chaos – Oyster Woman

V Drift of Chaos – Chanteurs du Monde

VI Drift of Chaos – Butterfly Woman

The Styx

VII. The Styx I

VIII. The Styx II

[no IX in folder]

Untitled Sequence

X. Sunset Creatures

[no XI in folder]

XII. The Snow Looks in at the Window

XIII. The Light Bursts out of the Window

XIV. The Sentinels

[no XV in folder]

XVI. The Green Sphynx [sic]

These paintings (based on their titles as compared to the list of titles from the 1933 exhibition catalog) do not appear to have been shown in 1933. Loy may have sent the Maurice Poplin photos to Levy as possible paintings to include in the 1933 exhibition, or, they may have been part of a planned second exhibition that never came to fruition. Loy’s 1933 paintings did not sell, and Levy wrote Loy in 1934 about the “possibility of another Loy exhibition for next year,” stating, “I become more and more convinced that it is a good psychological moment. The vogue here has changed radically (through Florine Stettheimer’s designs for the Gertrude Stein Opera). Whereas last year your pictures were criticised for being feminine and personal, now everybody is crazy for pictures which are ‘feerique’ and candy box and magical.”20 He advised her however to “[add] color this time.”

Loy’s unexhibited paintings focus not on the heavens but on the sea, and many are painted in shades of green and blue. These paintings appear darker in theme as well: the opening sequences, titled Drift of Chaos and The Styx, along with the ominous painting titled Sentinel, suggest Loy’s apprehension of impending doom, akin to the sense of foreboding in Oelze’s painting “Expectation,” discussed by Loy in Insel. As Linda Kinnahan points out in “Italian Retreats,” Loy portrayed Carrara as a “marble sentinel” in her 1928 poem “The Mediterranean Sea,” and this poem and painting may be in conversation.

While much about these unexhibited paintings remains unknown, Loy’s novel Insel offers some intriguing clues. Loy often used one form of art to reflect on her designs in another medium (Burstein 190), and in Insel Loy offers a critical appraisal of Oelze’s paintings, but also describes her own. In one scene Insel spots “some photographs of paintings lying on the table” in Mrs. Jones’s apartment, and asks Mrs. Jones “Whose pictures are these? […] Who could have done these?” adding “You are an extraordinarily gifted woman.” Mrs. Jones responds

‘Those’ are my ‘last exhibition’ cancelled the moment the dealer set eyes on them […] I felt, if I were to go back, begin a universe all over again, forget all form I am familiar with, evoking a chaos from which I could draw forth incipient form, that at last the female brain might achieve an act of creation.

Mrs. Jones adds, “I did not know this as yet, but the man seated before me holding a photo in his somewhat invalid hand had done this very thing — visualized the mists of chaos curdling into shape. But with a male difference” (Insel 37).21

In several scenes Loy alludes to her paintings and designs as she describes Mrs. Jones or Insel. For instance, in one scene Loy transforms Mrs. Jones’ apartment into an “irreal aquarium” and the sleeping Insel into “a creature of the deep sea” through her description of the “half-light softly bursting the dark” (109), a description that may allude to one of her lamp designs (see “Mina Loy’s lampshade shop”). As Loy describes Mrs. Jones, her language becomes painterly:

Because I found the place somewhat chilly when sunless — I had thrown a great white blanket over my thin dress. […] Fairly inflexible — it curved around me loosely, encaving me — its stiff corner trailing off like a sail. I sat on the edge of the couch at the feet of that rigid flotsam — in a huge white shell. […] Somehow, unable to dissolve into mist, and thus too dense to enter a mirage, the nearest I could conform to the arid aquatic was in becoming crustacean. (109-110).

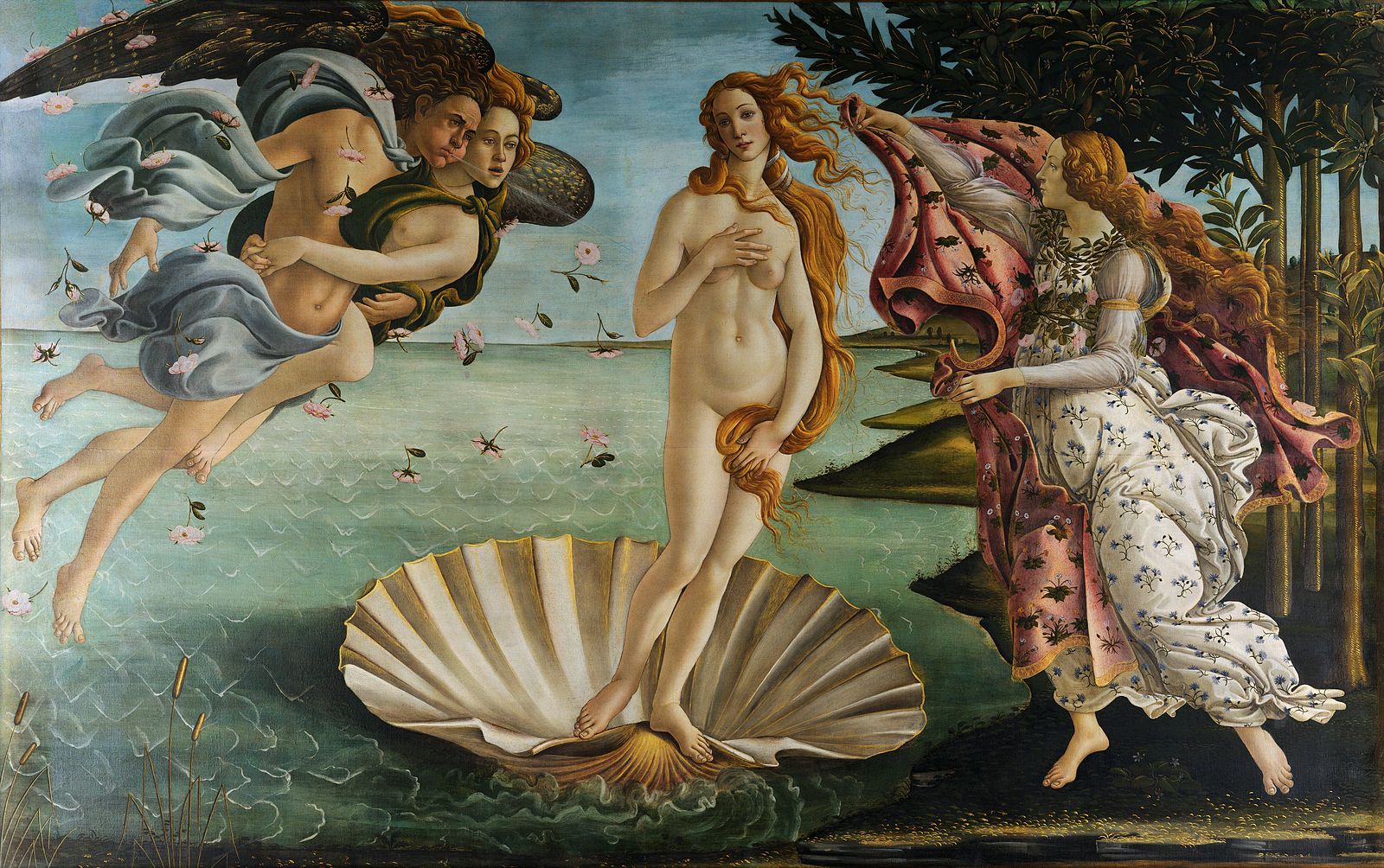

Loy’s description of Mrs. Jones resonates with the imagery of her undated (c. 1930s) “Oyster Woman” painting, and both text and painting allude to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, which Loy had likely viewed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In classical mythology Venus, the Roman Goddess of erotic love, took shape from sea foam. Loy’s painting depicts a woman whose body has been replaced by a white shell, which indeed appears to trail behind her like a sail. Loy’s description of Mrs. Jones sitting in a “huge white shell” also echoes Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. Mrs. Jones’ attempt to become a Surrealist Venus fails: she cannot leave behind her human body to “dissolve into mist,” and “becoming crustacean” is all she can do to conform to the “arid aquatic.”

The “arid aquatic” refers to Mrs. Jones’ apartment transformed by dim light into an “irreal aquarium,” but figuratively, “arid aquatic” may refer to the cultural “sea” that generated Venus and the erotic ideals of women underpinning both classical mythology and Surrealism. With the word “arid” Loy subjects these ideals to her corrosive irony. “Becoming crustacean” resonates with “Oyster Woman” but may also allude to Loy’s “Lobster Boy” object (c. 1930s) which critically engaged Surrealist erotic ideals (see “Surrealist Objects, Fashion, Design”).

Loy’s depiction of hybrid creatures in her 1930s paintings — her snail-people, moon-angels, oyster woman, and butterfly woman — also resonates with the work of other Surrealist women painters and poets. Whitney Chadwick points out that in many Surrealist paintings by women, hybrid human-animals function as “symbolic intermediaries between the unconscious and the natural world […] they replace […] the image of woman as the mediating link between man and the ‘marvelous’” (79) (See the discussion of Leonor Fini and the sphinx).

Loy’s poems from the Paris years also depict human-animal and angel-animal hybrids (see “Surrealism in Loy’s Paris-era Poetry”). In her poetry Loy adapts the Surrealist image to juxtapose the angelic or human with the animal: through these mixtures she generates the potential for a new definition of the human, but with a female difference.

Loy’s unexhibited paintings from the Paris years, clearly organized as a coherent group, may prove to be, alongside Insel, her most sustained engagement with Surrealist themes and techniques. Both the novel and the unexhibited-yet-collected paintings constitute semi-visible, en dehors garde, collections. Did Loy refer to her paintings and lamps in Insel as a way to “exhibit” works that had been sold (lamps) or overlooked (paintings)? An approach to Insel as textual gallery or “imaginary museum” reveals that Loy’s visual creations from the 1920s and 30s need to be read alongside and in conversation with Insel and Loy’s other texts from this era (see “Surrealist Poetics”), just as Loy’s Insel as a self-curated museum is in dialogue with the actual museum-gallery network she engaged in Paris and New York.

- On Loy’s role as Levy’s agent see Burke “Loy-Alism” 67-74 and Becoming Modern 377, and Elizabeth Arnold “Afterword” to Insel (182).

- Loy’s lists of her bottles can be found in The Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 6, Folder “Paris: Mina Loy’s Bottle Collection.”

- Barr, Levy, and Arthur Everett Austin Jr (head of the Wadsworth Atheneum) were all students of Paul Sachs at Harvard, who taught museum administration, part of a group of influential interpreters of modernism that Steven Watson calls the “Harvard modernists” (Schaffner and Jacobs, “Introduction” Portrait 12; Steven Watson, “Julien Levy: Exhibitionist and Harvard Modernist” in Schaffner and Jacobs, Portrait 80-83). MoMA acquired many works through the Levy Gallery, including its collection of Atget photos (Schaffner, “Alchemy” 29; Watson, “Julien Levy” in Schaffner and Jacobs, Portrait 89).

- With the aim of educating an American public, Levy’s book includes “painting, literature, photography, cinema, politics, architecture, play and behaviour” (4) organized by categories such as “fetishism,” “politics,” “play,” and “dream.” As Schaffner points out, “Its fluid framework was perfectly suited to Levy’s claim that ‘Surrealism is not a rational, dogmatic, and consequently static theory of art’” (Portrait 96).

- Lewis Kachur notes that “Levy wanted to blend native amusements with the Exposition’s bold use of Surrealist display, thereby appealing to the carnivalesque aspects of American popular culture” (Displaying 107). The plan included a surrealist fun house walk, a house of horrors with waxwork figures, and a human kaleidoscope (107-8), ), e.g. a “combination of dime museum and industrial display” (111). The experience of dream and hallucination were to be enacted in the gallery’s design, which was in the shape of an eye, with “malleable architecture” including an audible staircase, rocking floors, and pneumatic walls (108, 110).

- Ingrid Schaffner discusses these screenings in “Alchemy” (36) and Lisa Jacobs includes the screenings in her detailed “Chronology” in Portrait 179, 188-9.

- See Linda Kinnahan’s discussion of Loy, the Levy Gallery, and the importance of photography 77-82. Also see Schaffner, “Alchemy” 26-28, and Ware and Barberie, Dreaming in Black and White.

- In his 1937 fantastic art exhibition, Barr exhibited one or two works by Katherine Dreier, Georgia O’Keeffe, Eileen Agar, Meret Oppenheim, Leonor Fini, Hannah Hoch, and Valentine Hugo. Levy’s Gallery featured and/or gave solo exhibitions to Lee Miller (1932), Berenice Abbott (1932, 1937), Mina Loy (1933, 1937), Katherine Dreier (1934), Leonor Fini (1936, 1939), Alicia Halicka (1938), Gracie Allen (1938), Frida Kahlo (1938), Maud Morgan (1938, 1942), Maria Lednicka (1938), Marion Souchon (1939), Milena (1940), Tamara de Lempicka (1941), Catherine Yarrow (1943), Dorothea Tanning (1944, 1948), Xenia Cage (1943-4), and Kay Sage (1944, 1947). See Jacobs, “Chronology of Exhibitions” Portrait 173-189.

- Sarah Hayden in her discussion of the process of Insel’s composition and publication notes that Loy understood Insel as part of her “immense experimental prose work” “Islands in the Air,” which Hayden describes as “an ambitious, categorically unstable project to encompass the entirety of her autobiography in a fictionalized prose form” (“Introduction,” Insel 2014, xiv).

- I quote from Elizabeth Arnold’s original edition of Insel (Black Sparrow Press, 1991) but discuss Sarah Hayden’s new Introduction to Insel published by Melville House (2014).

- For varied interpretations of this relationship in Insel, see Arnold, Armstrong, Ayers, Bronstein, Gaedtke, Hayden, Miller, and Walter. On the importance of Christian Science as it mediates Mrs. Jones’ relationship to Insel and surrealism, see the essays by Tim Armstrong (Salt 204-220) and David Ayers (Salt 221-247). See too Sarah Hayden’s treatment of Insel in the context of Christian Science in her recent edition of Insel and in Curious Disciplines. On Loy and Christian Science see also Lara Vetter, “Theories of Spiritual Evolution, Christian Science, and the ‘Cosmopolitan Jew’: Mina Loy and American Identity.” Journal of Modern Literature 31.1 (2007): 47-63.

- Sarah Hayden argues that Loy raises Insel’s morphine addiction in the novel as a possibility that Mrs. Jones ultimately rejects, while in the alternate unpublished ending Loy wrote, “The Visitation of Insel,” Mrs. Jones accepts the fact of Insel’s addiction and casts Insel’s surrealism as an effect of morphine (“Introduction” Insel 2014, xxvii-xxxi).

- Christina Walter has persuasively argued for this connection between “Die Irma” and “Frieda” (682-83).

- The 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism exhibition catalogue mentions the Frieda/Kafka connection (228) and states that the sketch was “given anonymously,” although MoMA’s provenance research suggests that the museum purchased the sketch. In a 24 January 1937 letter to Alfred Barr, Oelze states, “I was in such a bad condition this last month in Paris – especially psychically – so that I could not finish the picture, Frieda, and at the end destroyed it. I am very sorry for it – because I promised it to you – but I do hope you understand and will forgive me” (Museum of Modern Art Archives). In his correspondence with Oelze about the exhibition, Barr refers to Mina Loy’s role as agent, suggesting that Oelze’s inclusion was facilitated by Loy (Museum of Modern Art Archives).

- In a March 19, 1938 letter to Loy, James Laughlin mentions that he has spoken with Julien Levy who hopes to arrange the book’s publication, and suggested publishing a section in the New Directions anthology to generate interest. Laughlin asks Loy to contact him when he returns from Paris in June 1938 if she is interested. (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 7, James Laughlin Correspondence). In a Summer 1952 letter to Laughlin sent from 5 Stanton Street, Loy mentions that she is sending some typescripts, and adds a comment on Insel and drug addiction, suggesting that she had begun conversing with Laughlin about publishing the novel (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 7, Folder Mina Loy Correspondence from the Bowery 1949-1954). Sarah Hayden writes that in December 1953 Laughlin turned down Insel (“Introduction,” Insel 2014, xviii). A series of letters from Loy to Laughlin written from Aspen in the late 1950s and early 1960s indicates that Loy actively pursued the possibility of Laughlin’s publication of Insel; she mentions that one of her children found the manuscript which Julien Levy showed to Laughlin years ago; she clarifies that she does address Insel’s drug addiction in one part of the novel; and in a 1960 telegram she grants Laughlin permission to publish a part of Insel, apparently at his request (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 6, James Laughlin: Letters from Mina Loy). An August 5 1959 letter from Jonathan Williams to Loy mentions that he heard Laughlin had visited her the previous month in Aspen (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library). In a ca. 1960 letter to Joella Bayer, Julien Levy states that he was happy to learn that she has rescued Loy’s book from oblivion (presumably Insel) and is editing it for New Directions (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, “Correspondence” Box 3). Sarah Hayden writes that Laughlin corresponded with Elizabeth Sutherland at Simon and Schuster about Insel and Loy’s “Islands in the Air” manuscript, but Sutherland also passed on the novel in 1963 (Sarah Hayden, “Introduction,” Insel 2014, xviii).

- Although Loy was painting at this time, and critically engaged Surrealism in her 1930 painting “Surreal Scene,” which can also be regarded as a critical framing of male Surrealist art, her turn to narrative indicates how, as Jessica Burstein has argued, Loy often used one art form to comment on her designs in a different medium (Cold Modernism 190).

- Loy “developed and edited the novel after her relocation to New York in 1936” (Hayden xviii), and Hayden speculates that Loy may have written the “Visitation of Insel” in 1938 (xxviii).

- On the exhibitions of Loy’s artwork at the Levy Gallery, see Carolyn Burke, “Loy-alism” in Schaffner and Jacobs, Portrait 70-71; Jacobs, “Chronology of Exhibitions” in Schaffner and Jacobs, Portrait 175, 180; Burke, Becoming Modern 377-379.

- Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, Box 6, Folder “Exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery 1933, photographs and reviews.”

- folder.

- Loy explored incipient form in Mi and Lo reprinted in Stories and Essays (see Burke 376).