In this section you can explore:

- Surrealist Objects and the Objectification of the Female Body

- “Lobster Boy”

- Loy, Dali, & Lobsters

- L’objet trouvée or the found object: Loy at the flea market

- The Surrealist Object, Fashion, and Interior Design

Surrealist Objects and the Objectification of the Female Body

Interest in the Surrealist object grew in the 1930s. As Whitney Chadwick argues, “Capturing the images of the dream in reality, crystallizing the objects of desire and affirming the magic link between the unconscious and the real world, the Surrealist object became the perfect meeting point of Surrealist theory and practice” (118).

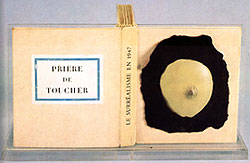

Chadwick notes that “Surrealist objects by male artists often have an explicitly erotic content (Bellmer’s Dolls, Duchamp’s Please Touch), disturb by means of violent juxtapositions (Man Ray’s Gift, Dominguez’s Conversion of Energy), or combine both functions (Dominguez’s Arrival of the Belle Epoque)” (118).

Male Surrealists objectified and fetishized different parts of the female body, but women also made Surrealist objects in the 1930s, which often commented on sexual objectification or explored facets of the object resonant with gendered experience. Objects by women were included in several important Surrealist exhibitions, including the 1933 “Exposition Internationale Du Surréalisme” at the Pierre Colle Gallery; at the 1936 “Exposition Surréaliste D’Objets” at the Charles Ratton Gallery; at the 1938 “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme”; at the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London; and at the 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism exhibition at MoMA.

In fact, a work by a female artist — Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup — became virtually synonymous with the 1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism exhibition; the MoMA was dubbed by Harper’s Magazine the “fur-lined museum.”1

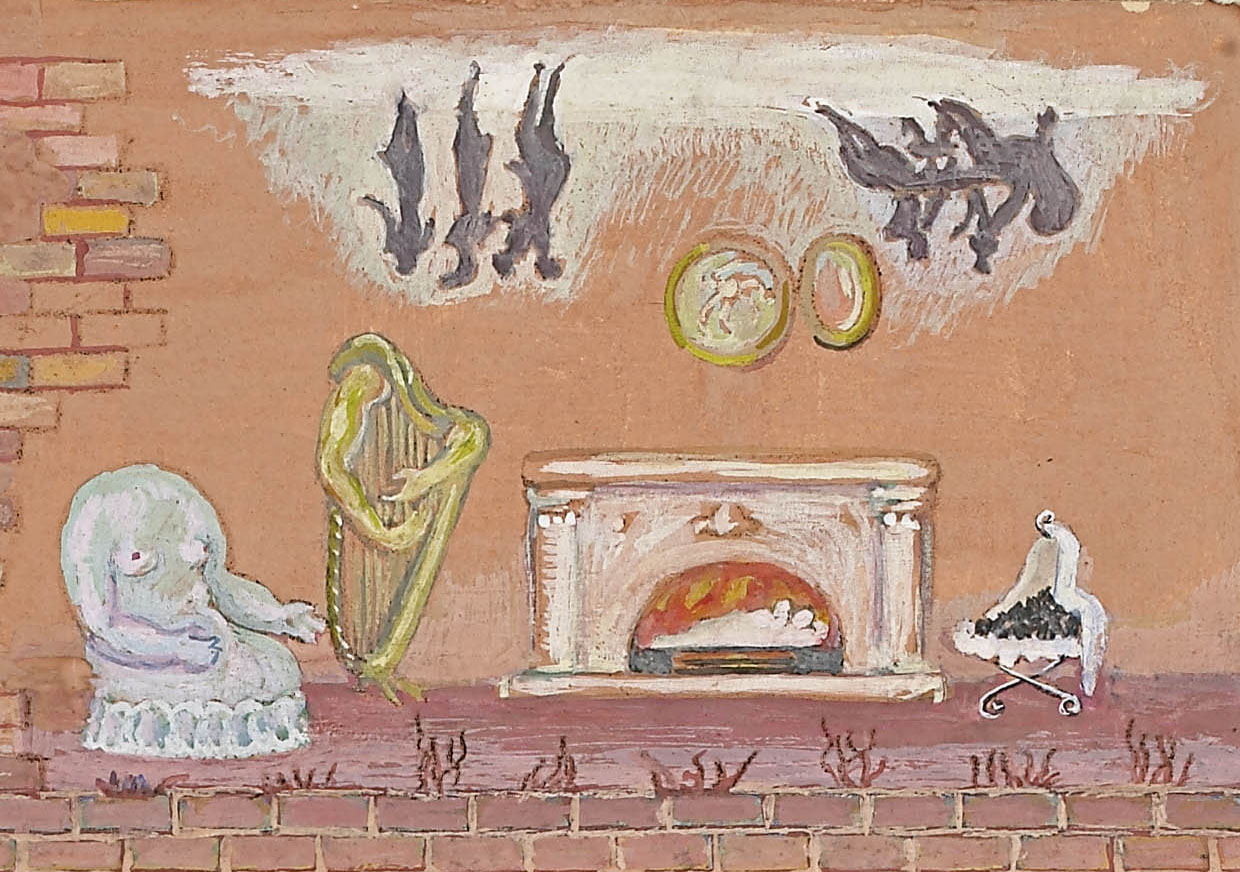

Surreal Scene (1930) comments on several incarnations of the Surrealist object, illuminating Loy’s thoughts about this form. In the upper right-hand corner of the painting, Loy depicts an armchair in the shape of a headless white woman’s body.

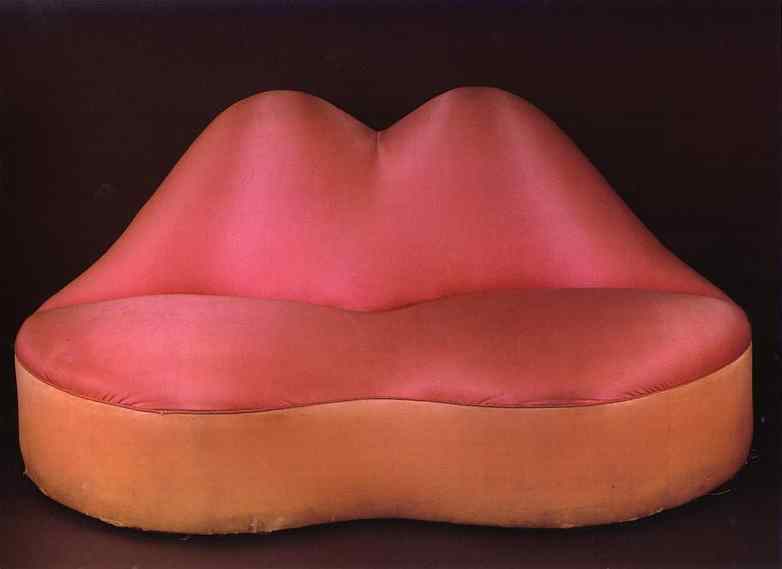

The chair conflates women with domestic comfort and/or sexual availability, as the woman-chair is literally a mindless thing positioned to physically receive others. Similarly, the headless harp has arms that are plucking strings, providing music for others in the room. In her set design for her play “The Pamperers,” Loy described “Picked people melted by a distinguished method among the upholstery” and commented, “the social fabric is a curtain” (see “The Pamperers”). Suggesting that arrangements of people and furniture reflect how class privilege and gender shape the social fabric, Loy’s woman-chair reveals woman’s material presence-intellectual absence in the “surreal scene.” This woman-chair may allude to and comment on the couch-body hybrid in Cocteau’s film Blood of a Poet (1930) which Dali would later respond to with his “Mae West Lips Sofa” (1936).

Similarly, in the upper left-hand corner of Surreal Scene, divided from the living room scene by layered brick to suggest the movement from domestic to public space, Loy depicts women walking in public as objects of sexual pursuit, but turns the tables by objectifying the men who pursue these women, depicting them as nothing more than disembodied arms. These disembodied arms form a contrast with the arms of the human harp, which we might infer are female.

In Freudian thought a fetish involves the “transference of the libido from the whole object of affection to a part, a symbol, an article of clothing” (Schaffner, Portrait 116). Rather than objectifying the feminine object of masculine desire, in the disembodied arms Loy objectifies the male libido, providing a critique of the Freudian fetish as it usually appeared in the work of male Surrealists (see “Criticism of Freud and Eros Obsolete”).

Loy also comments on the fetish object through the shoes worn by the otherwise naked woman or female mannequin in Surreal Scene. Just such a pair of woman’s shoes appear on a disembodied female leg in New York Dada (1921). A female mannequin’s legs with shoes are made to “dance” in Léger’s “Ballet Mécanique” (1924), and Umbo’s 1928 photo of a female mannequin’s disembodied legs focus on the shoes as fetishistic substitution for the female body (Schaffner, Portrait 120).

In contrast to these disembodied female legs with shoes, Loy’s painting presents the entire woman clothed in nothing more than shoes, as if to emphasize the ridiculousness of reducing a woman to her shoes.

“Lobster Boy”

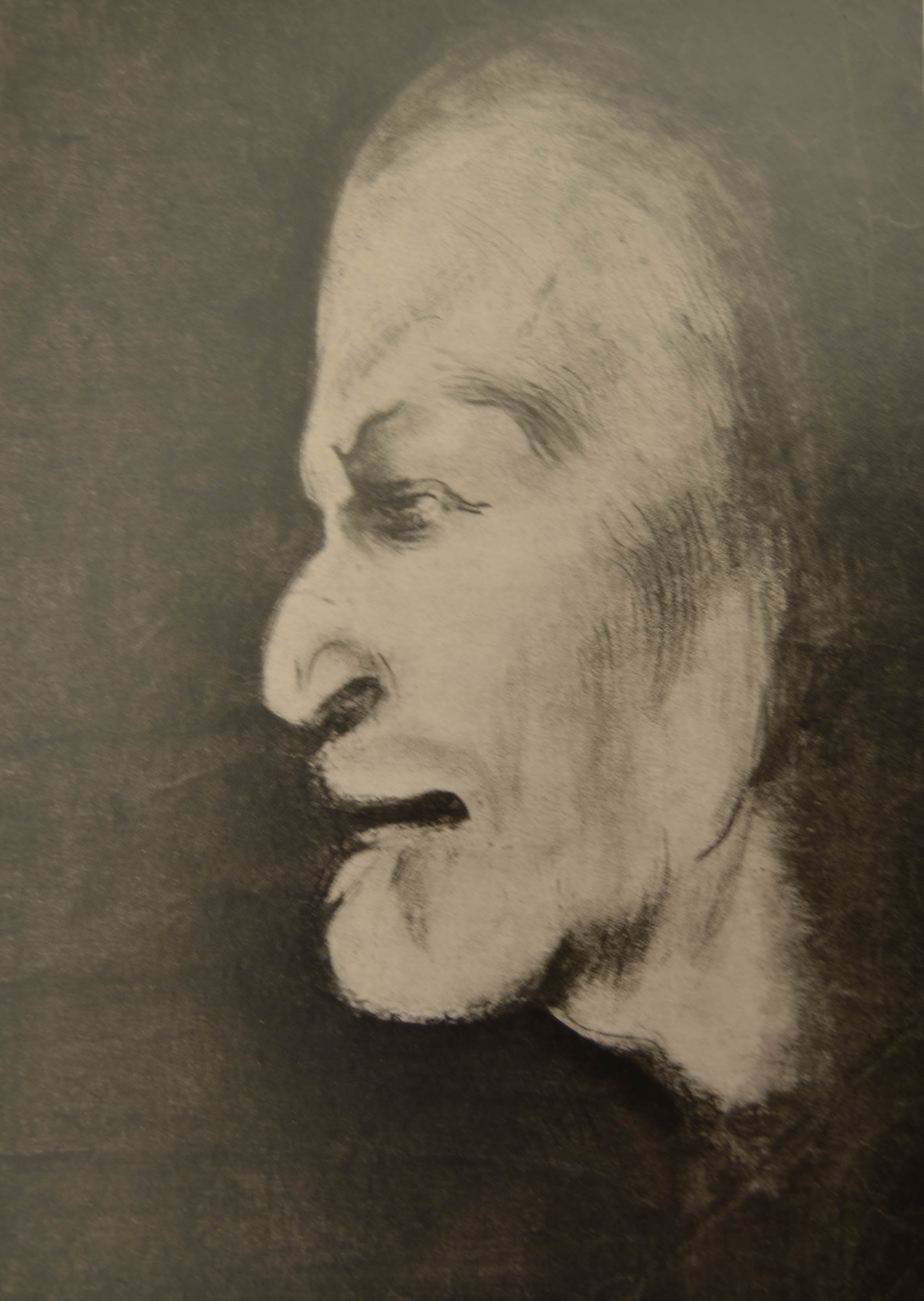

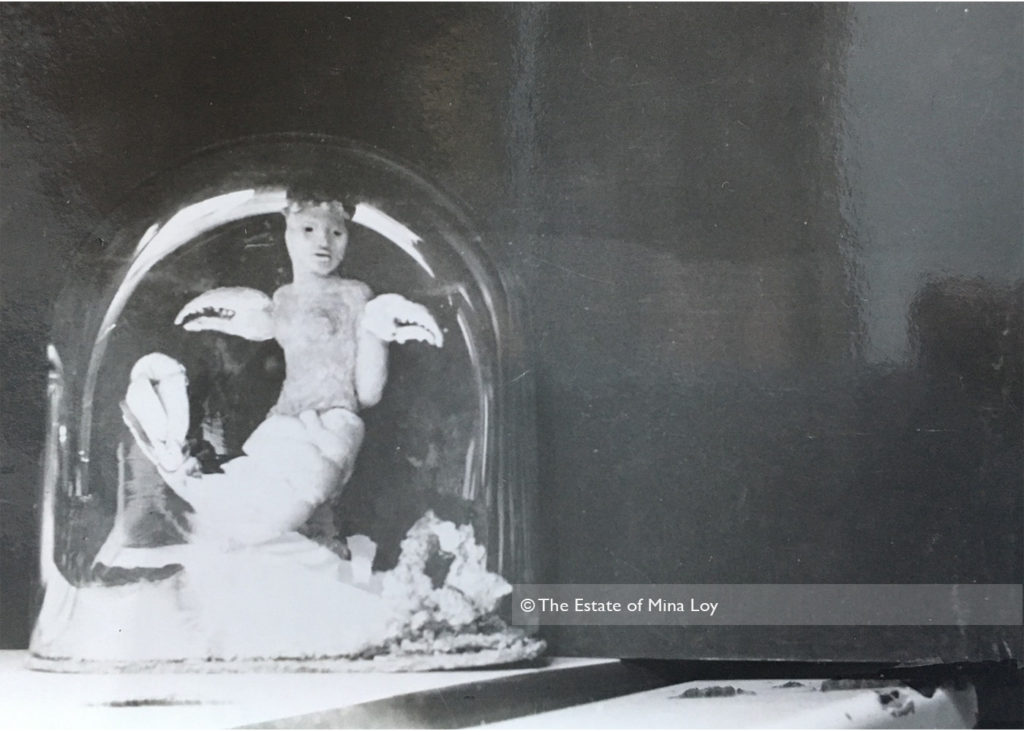

Critical of how Surrealists often objectified and fetishized the female body in their objects, Loy also created one of her own, called “Lobster boy”: although the object has been lost, a photograph of it displayed in Loy’s apartment remains (Roger Conover collection).2 Loy’s “Lobster Boy” object, although its precise date of composition is unknown, was likely created in Paris prior to her move to New York in late 1936, and reflects her interest in human-animal hybrids and in crustaceans of various kinds in her Paris-era work (visit the Lobster Boy StoryMap).

Loy’s object consists of a youth with a lobster tail in place of legs and lobster claws in place of arms, set in a small glass bell jar. The glass bell jar is not simply a container for the lobster boy, but evokes a water-filled aquarium in which the creature swims. Loy discusses the transformation of an apartment into an “irreal aquarium” in her surrealist novel Insel, and sought to create similar effects with her lamps and lampshades, transforming interior rooms to aquatic environments through the play of light and shadow.3

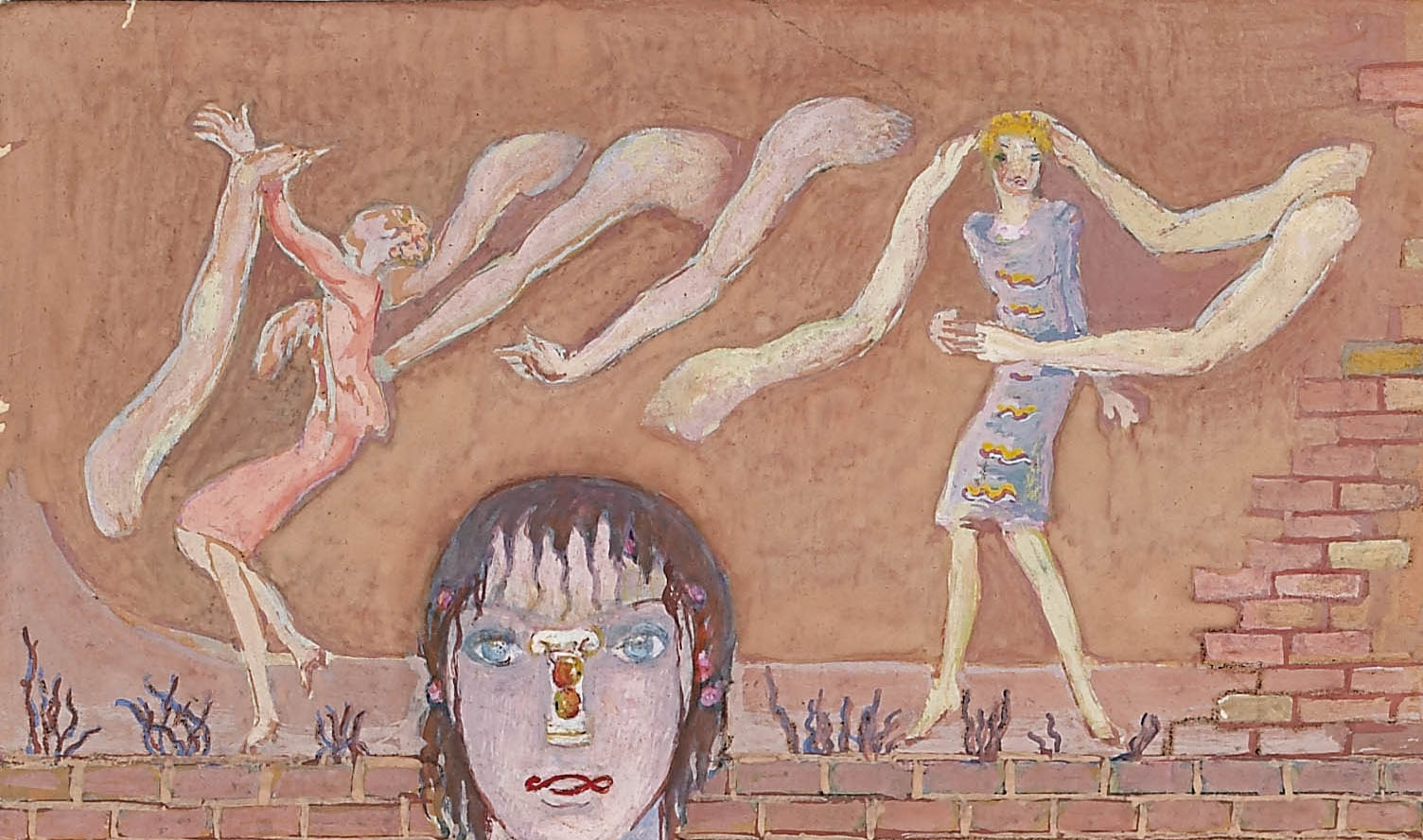

Although titled “Lobster boy,” the figure clearly has breasts. In 1925 Loy painted a fresco of mermaids and lobster-human hybrids on her bedroom wall at Peggy Guggenheim’s villa in Prasmousquier (Burke 334-5). Peggy Guggenheim wrote, “Mina painted a fresco in her bedroom. She conceived lobsters and mermaids with sunshades tied to their tails” (LLB82).

Loy’s “Lobster Boy,” like the figure on the righthand side of the fresco, appears to be Loy’s crustacean twist on the mermaid — the “Lobster Boy” has a lobster tail and claws, but a human head and torso. In the fresco, the mermaids appear to be female and the lobster figure’s gender is unclear, but it could be a model for or version of Loy’s “Lobster Boy.”

However, Loy’s “Lobster Boy” object with breasts suggests a hermaphroditic mixture of a lobster boy and female mermaid. The figure’s ambiguous or hybrid gender, coupled with its conjoining of human and crustacean forms, suggests new physical configurations of sex and gender. Human-animal hybrids challenged firm lines of sexual identity and expanded the realm of the natural: Loy would explore such hybrids in Insel and in her paintings and poems of the early 1930s.

While “Lobster Boy” is influenced by Surrealism, Loy’s interest in sexual hybridity and androgyny was longstanding: her earlier paintings had often portrayed androgynous figures (for example, La Maison en Papier 1906; L’Amour Dorloté par les Belles Dames 1913). In the 1910s hermaphroditism was explored by poets who (like Loy) were associated with the little magazine Others, including Frances Gregg, “Hermaphrodites” (November 1915) and Alice Groff, “Hermaphrodite-Us” (January 1916).4 H.D.’s “Hermes of the Ways” appeared in Poetry in 1913 and she also published in Others; in her April 1925 essay “Modern Poetry” published in Charm magazine (3.3), Loy cited H.D. as “an interesting example of my claims for the American poet who engages with an older culture,” adding that H.D. “has written at least two perfect poems: one about a swan” (LB96 160).

The head of the “Lobster Boy,” with its hollow eyes, suggests the head of a Greek or Roman statue. The figure appears to have a garland around his forehead, possibly an allusion to the laurel crown worn by Apollo and given to Greek poets and warriors. In her 1923 poem “Marble,” published in a prospectus for the Trans-Atlantic Review, Loy wrote:

Greece has thrown white shadows

sown

their eyeballs with oblivion

A flock of stone

Gods

perched upon pedestals (LLB96 93)

In merging human and lobster in this statue-like figure, Loy was likely generating her own rendition of classical myth, joining artists such as H.D. whose poetic transformations of Greek myth were shaped by her modern, non-binary understanding of sex and gender. Loy also commented on classical myth, specifically the birth of Venus, in her painting “Oyster Woman” from the 1930s, which merges human and crustacean to critically engage erotic ideals of women (see “I’m not the Museum”).

Loy’s “Lobster Boy” also shares qualities with her poems from the 1920s, indicating the varied forms in which Loy explored her ideas about hybridity at this time. As Linda Kinnahan argues in “Italian Retreats,” Loy’s visit to Carrara and its marble quarries informed her poem “The Mediterranean Sea” (1928) and specifically her depiction of Carrara as a “marble sentinel” (LLB96 101-2) standing at the “liminal meeting space of mountain and sea.” Carrara stands over “amphibian babies / as they rise // from the Ligurian gullies / their polished thighs / armoured with aqueous ashes / of the tinselled sands” (LLB96 102). Loy draws on feminine and masculine, maternal and military, human and amphibian qualities in her depiction of Carrara and its surroundings, inviting comparison to her “Lobster Boy” object.

Tara Prescott has similarly noted that in Loy’s poem “Der Blinde Junge” (c. 1922), Bellona the Roman Goddess of War gives birth to “eyeless offspring,” a “young blind boy who was once a soldier but now begs for coins on a Vienna street by signing and playing a harmonica” (154). This boy, blind like the “Lobster Boy” and the Greek statues Loy describes in “Marble,” merges feminine and masculine, maternal and military, human and animal qualities. Loy describes “A downy youth’s snout / nozzling the sun/ drowned in dumbfounded instinct” (LLB96 84) and Prescott argues that this imagery, “especially [the] piglike snout (evoking Songs to Joanne’s Pig Cupid) — all point toward an oddly desexualized being” (158). In creating new mixtures of the human and the animal Loy blurred the lines between masculinity and femininity (see “Surrealism in Loy’s Paris-era Poetry”).

Loy, Dali, & Lobsters

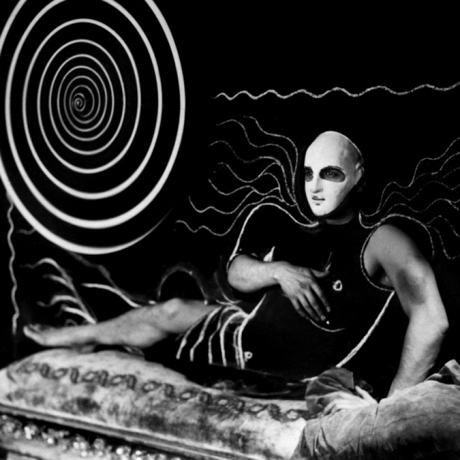

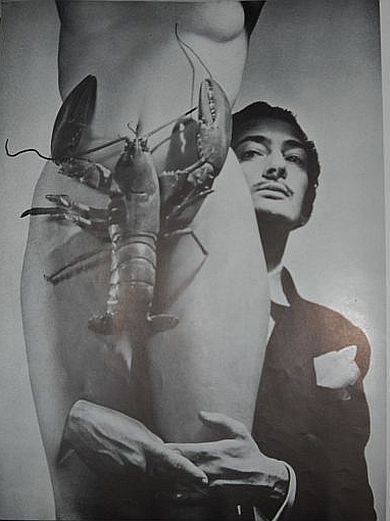

While many Surrealists were interested in sea life and in crustaceans, Salvador Dali prominently featured lobsters in many works in the later 1930s. Loy knew Dali through her work as Paris agent for the Julien Levy Gallery, and stored his painting “The Persistence of Memory” (1931) in her 9 Rue St. Romain apartment prior to shipping it to Levy in New York (Burke 385, “Loy-alism” 72). Although Loy’s “Lobster Boy” object cannot be precisely dated, her relationship to Dali invites a comparison of how each artist uses the lobster. Dali’s lobsters began to appear in his work in 1934, most famously in “Aphrodisiac Telephone” (1936), on the dress he designed with Schiaparelli (1937), and in his “Dream of Venus” Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair, which featured nude mannequins with lobsters in place of bathing suits. Julien Levy and Woodner Silverman had made the original designs for this “Surrealist House” (Kachur, Displaying 106).

Spectators entered Dali’s pavilion through the legs of a woman, the “very womb of Venus” (Kachur, Displaying 133), and the interior resembled an underwater scene, including tanks with female mannequins and swimming, bare-breasted female mermaids (Kachur, Displaying 137, 140).

Mina Loy’s letters to Julien Levy from Paris indicate that she enjoyed representing Dali for the Levy Gallery, although her representation of Dali apparently ended in 1935, and she noted Dali’s sensationalist advertising techniques in her novel Insel.5.

In George Platt Lynes’ 1939 Surrealist photo of Dali posed behind the female mannequin at the Dream of Venus pavilion, Dali’s placement of the lobster suggests the addition of male genitalia to the woman’s torso, challenging the assignment of sex and gender, while the prominent lobster claws may signify the castrating potential of female sexuality. Lucy Flint points out that in male Surrealist art, “The female, seen in horror and longing as both victim and victimizer of male sexuality, is often a crustacean or insectlike form” (see “Surrealist Histories”). Lynes’ placement of Dali’s right hand, which appears to emerge from a slit in the mannequin’s right thigh, suggests Dali’s phallic penetration of the female body. Employing the lobster to simultaneously challenge conventions of gender and to provoke anxiety about male control and female sexuality, this photo provides a useful point of contrast with Loy’s “Lobster Boy” object, which conjoins rather than superimposes forms to generate a true hybrid.

L’objet Trouvée or the Found Object: Loy at the Flea Market

In addition to her “Surrealist object,” Loy engages the “objet trouvée” or found object, a particular kind of Surrealist object defined by André Breton in “Equation de l’objet trouvée” (1934) and in a passage from Mad Love (1937) that describes his walk with Alberto Giacometti through the Paris flea markets. Giacometti, in trying to resolve how to make the head of a sculpture, was drawn towards a fencing mask that solved his problem. Although the found object may be mass produced, the manner of its finding, as in Giacometti’s case, is singular and subject to chance, unconscious desire, and unplanned intuition (Hopkins 90-91). The found object would play an important role in the art of Joseph Cornell and in Loy’s late constructions made from materials found on the Bowery.

In Paris (prior to the publication of Mad Love) Loy “found” objects but with a different aim than Breton. Many “found” objects were actually purchased, and Loy paid careful attention to the economics of aesthetic value. Loy frequented the Paris flea markets to search for bottles for her bottle collection and to use as lamp bases for the lamps she sold in her shop: she found her objects and materials with a practical purpose in mind. Simply put, Loy needed to make a living. In this she was less an idle flaneuse strolling through the flea market than a glaneuse or “gleaner,” anticipating the film “Les Gleaners et La Glaneuse” by Agnes Varda.

As Virginia Bonner argues, Varda explores gleaning out of sympathy with those who glean to survive, and Varda considered her art as a kind of gleaning, a stance consistent with Loy’s (Senses of Cinema). Bonner states “in our capitalist patriarchy, one learns to prize the new, the young, the beautiful – the marketable; Varda instead revalues the used, the aged, even the unsightly.” Loy’s thrift, need to make a living, and eye for design guided her gleaning, just as revaluing, recycling, and artisanal handicraft defined her ambivalent engagement with the commercial marketplace.6 Julien Levy as an aspiring filmmaker recorded Loy as “La Glaneuse” — beginning in 1932, Levy made “short experimental films of artists in action” including one of Loy at the Paris flea market (Burke 378; Burke, Loy-alism 69).7

Levy often accompanied Loy on these excursions to the flea market, and in doing so initiated a trans-Atlantic connection between Loy and Joseph Cornell that would solidify when Loy moved to New York: Levy bought boxes and watch parts at the Paris flea market and gave them to Cornell, who made them into small surrealist objects that Levy exhibited at his New York Gallery (Burke 379).

Loy addressed her departure from the male Surrealists’ understanding of the found object in an episode from her novel Insel, in which Insel states of a “still life” in Mrs. Jones’ flat that “It would surely be of the greatest interest to Freud” (166). Mrs. Jones responds:

The still life that intrigued him was a pattern of a ‘detail’ to be strewn about the surface of clear lamp shades. Through equidistant holes punched in a crystalline square, I had carefully urged in extension, a still celluloid coil of the color that Schiaparelli has since called shocking pink. Made to be worn round pigeon’s ankles for identification, I had picked it up in the Bon Marché.

Out of this harmless even pretty object an ignorant bully had constructed for me, according to his own conceptions, a libido threaded with some viciousness impossible to construe.

I was astounded. (166-7).

In essays written in Paris Loy expressed contempt for Freud’s understanding of the female libido: Mrs. Jones is incensed that Insel blithely echoes Freud while ignoring the innovative thrift and economic necessity legible in the lampshade design.

The Surrealist Object, Fashion, and Interior Design

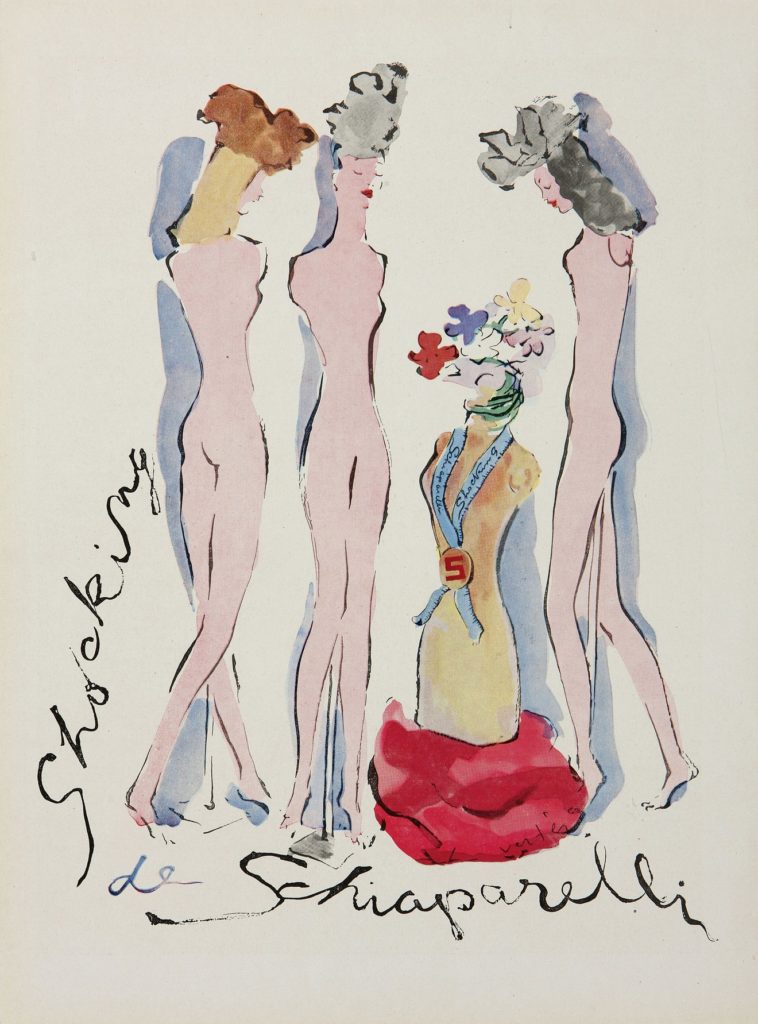

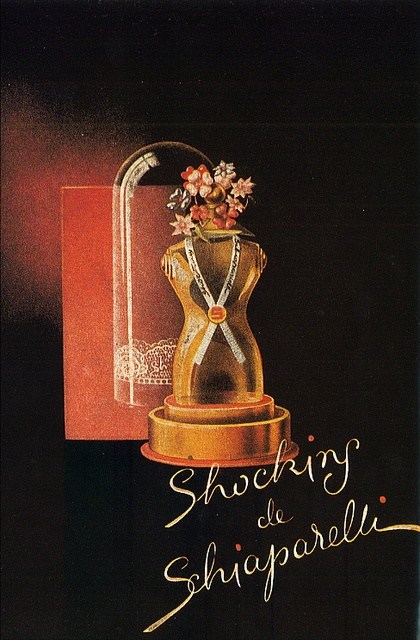

As Loy’s allusion to Schiaparelli indicates, the Surrealist object “spilled over into the arena of fashion and jewelry design” (Chadwick 118) and for Loy, also spilled over into interior design and objects for the home.8

Even as she criticized the Surrealists’ objectification of women in her artwork and poems of the 1920s and early 1930s, Loy recognized femininity as a marketable commodity and participated in commercial fashion as both a designer (of dresses and objects) and muse-model (see Linda Kinnahan’s StoryMap analysis of Loy’s dress designs; see also the discussion of Loy as model in “Self-Portraits”). Loy’s recognition of femininity as a performance and saleable commodity extended to her treatment of her own dress and appearance. Cristanne Miller sees a schism between Loy’s treatment of femininity in her poetry and in her self-presentation:

Her deceptive appearance of femininity is not reflected in the nongendered speaking voice and radical linguistic structures of her poems. These contrasts represent the two types of lingua franca available to her in all the cities she temporarily called home. As an attractive and stylishly feminine woman, she received a degree of attention not granted most of her poetic peers. Femininity was a known coin. At the same time, within the avant-garde in Paris, Florence, and New York, an antisentimental, language-focused, gender-neutral (or masculine) poetic style was the coin of value (120).

Miller’s analysis suggests that Loy fashioned her art and appearance with a different audience (and consumer) in mind, and modulated her designs and performance of gender accordingly. Susan Dunn and Jessica Burstein see less of a contrast or contradiction between Loy’s poetry and fashions, than an emphasis on the role of the artist as designer that varied with the medium Loy used (Cold Modernism 152, 190; “Fashion Victims”).9 As Dunn argues, “Loy felt that fashion was a medium that could be used to cross boundaries, not just of gender but of aesthetics as well” (“Fashion Victims”).

While Loy used fashion to cross boundaries, differing audiences and commercial markets shaped her poetry, her art, her designs, and her negotiation of femininity, as Miller emphasizes. Put another way, to what extent did Loy interrogate and make use of the conflation of woman and mass culture and the feminization of the commodity (Huyssen), as she participated in the fashion economy? How did the audience for a particular work shape Loy’s navigation of commercial and artistic aims?

In 1923 Loy showed a painting titled “Marchands de New York” (Markets of New York) at the Salon d’Automne, and in the kind of fluid movement between studio, gallery, and store that marked Loy’s engagement with fashion, in 1925 she created works titled “Jaded Blossoms” to be sold in those New York markets. In Carolyn Burke’s words:

Her latest fantasy, devised to earn the money for a larger apartment, crossed the traditional still life with Cubist collage. She cut leaf and petal shapes from colored papers, layered them to form old-fashioned bouquets, and arranged these pressed flowers in decoupe bowls and vases painted with meticulous attention to surface texture. These ‘arrangements’ were then backed with god paper and set in Mina’s flea-market frames: instant antiques, they looked expensive but were made from the cheapest materials (338-9).

Peggy Guggenheim and Laurence Vail took the “Jaded Blossoms” to New York, where they were exhibited and sold at Wanamaker Department store’s Belmaison gallery, Macy’s Gallery, and Cargoes Gallery.10 These objects garnered attention including a review in The New York Times (April 19, 1925), which called Loy a “poet as well as a designer” and the “Jaded Blossoms” “a modern version of the fashionable early American pasted paper decorations.” The New York City Record (April 1925) described Loy’s designs at length:

This title [Jaded Blossoms] does scant justice to Mrs. Loy’s very charming handicraft and painting, the pictures combining these two things, since they are cut out of paper, layer imposed on layer petal fashion, and they are painted, except in the occasional instances where this craftsman artist finds a paper of just the shade she requires. The flowers are ‘arranged’ in quaintly shaped bowls and jugs (in these the reproduction of surfaces is meticulous) and placed against gold-paper backgrounds, one particularly stunning bowl of flowers having a sheeny green paper behind it. Since they are all shown in Victorian contemporary frames (things of quaint joy of themselves) the decorative effect of each picture is extremely of that now fashionable [period]. Peggy Guggenheim Vail who brought the little collection of Mrs. Loy’s work in this field from Paris, is acting as horticultural-curator of the exhibition… (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, Box 6)

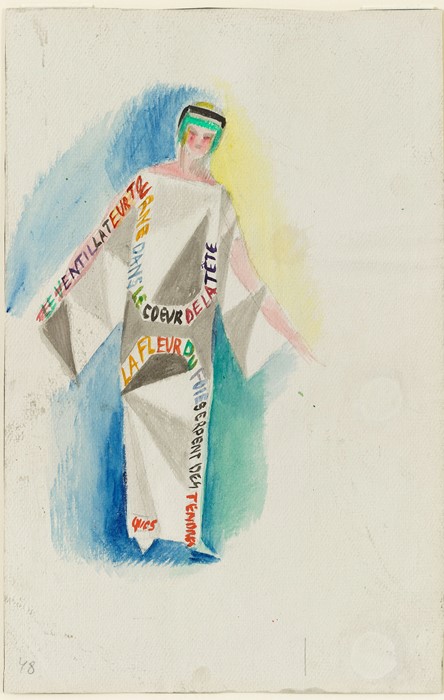

With the successful sale of her Jaded Blossoms objects in 1925, Loy pursued ways to merge art and commercial design. The Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris (April-October 1925) indicated the success of the applied arts, and Loy studied the exhibition carefully (Burke 339-340). Other women artists associated with the avant-garde exhibited designs: on display for instance were Sonia Delaunay’s simultanist fabrics, dresses, and shoes (Burke 340). Delaunay crossed the boundary between painting and fashion in her clothing designs, but also mixed fashion and poetry in her “dress-poetry” (robes-poemes) which juxtaposed lines of dadaist and surrealist poetry by Tzara and Soupault with geometric colored shapes.

Loy’s lamps have been discussed by Carolyn Burke as an example of Art Nouveau style, but the dates of her lamp shop (1926-1930) invite us to explore how Loy also engaged with Surrealist aesthetics in the designs of her lamps, the bases of which had been found by Loy in the flea market (Burke 338) (see “Mina Loy’s Lamp Shop”).

A number of woman artists, along with Salvador Dali, Man Ray, and others, pursued intersections between Surrealism and fashion. Thus the kinds of artistry evident in Surrealist objects exhibited at galleries and museums extended to objects intended for the consumer market. Meret Oppenheim and Leonor Fini created Surrealist objects but also made objects and jewelry for Surrealist designer Elsa Schiaparelli (Chadwick 122). For instance, Leonor Fini designed the Mae West inspired bottle for the perfume Shocking (1936), named after Schiaparelli’s signature color Shocking Pink.

Similarly, in 1940 Loy sold a jewelry bottle design to Helena Rubinstein which she called Pipes of Pan, made from recycled glass containers for cigarettes, renamed “Syrinx” by the company (Burke 301). Helena Rubinstein advertised her perfumes in View, Charles Henri Ford’s magazine that featured Surrealist (and surrealist-influenced) art and writing.11 Loy’s clever reuse of these glass containers, considered by most as trash, is a twist on the found object that echoed her reuse of bottles as lamp bases and anticipated her use of trash found on the street as the material for her Bowery collages. Repurposing used or discarded materials in new forms allowed them to enter the marketplace with a new claim on aesthetic and in turn economic value. These object transformations often permitted critical commentary on the consumer market.

Loy wrote a poem that she hoped could help “launch the Syrinx bottle,” which she typed in a letter dated July 15, 1940 to Mr. Titus at the Helena Rubenstein company12:

Fragrance is harmonious on the air

as music is a fragrance to the ear

The very silence of Perfume offsets it’s (sic) subtlety

Rubinstein of sound made melody

Helena Rubinstein presents: —

The scented symphony of her silent Syrinx

To whisper, from behind your ear,

To Everyman

ALLURE

As once the pipes of Pan ———-

Loy addressed the poem’s “two interlacing themes,” which she identified as “the musics (sic) of the two Rubinsteins” and “the silence of perfume,” adding “the first obviously could only be used by your firm but may not fit in with your firm’s policy, in which case I might transpose the poem; or you might care to purchase the third line as a Perfume slogan. I would require any firm using this poem to allow me to submit an illustration for it, should one be needed, before the firm decided on an illustration by any other artist.”

The permeable boundary between lyric and advertisement, poem and perfume, indicates that Loy did not position the lyric (the most idealized of poetic genres) outside of the marketplace, even as she used many of her poems to critically comment on the fashion industry, class, and economics.

- Emily Genauer, “The Fur-Lined Museum,” Harper’s Magazine, July 1944.

- Carolyn Burke writes that “Cornell kept in his files, possibly for future use, a photograph of the mantelpiece in Mina’s Rue St.-Romain apartment labeled ‘Paris, 1920s.’ It showed, in evocative juxtaposition, an owl statue, a harlequin figure, several old-fashioned toys, a figurine in a long robe, and a tiny Madonna in a bird cage” (407). The latter certainly sounds like another Surrealist object.

- Man Ray used a glass snowglobe in his c. 1935 object “Snowball” and Joseph Cornell often used glass bell jars as containers for objects, as in his “Untitled (Glass Bell)”, c. 1932, published in Minotaure 10 (Winter 1937) (Guigon, Cornell & Surrealism 51).

- See Suzanne Churchill’s chapter on Mina Loy in The Little Magazine Others and the Renovation of Modern American Poetry (Routledge 2006).

- Loy discusses Dali in Insel, Chapter 1 (p. 27): Mrs. Jones tells Insel that “Dali, for instance, is fated to the most extravagant of publicities. He is inclined to accept my theory, for some of the shrillest gags in his already fabulous advertisement were the result of sheer coincidence, yet pointing out plainly the effective procedure to be followed thenceforth. He told me it all originated with his first lecture on surrealism in Spain, when the mayor, who was acting as chairman, fell down dead at his feet, almost as soon as he began — a windfall for journalists.” Soon after, Mrs. Jones describes Insel in Dali-esque terms: “he shifted the part of a hard roll sandwich he was eating, out of the way, horrifyingly developing a Dali-like protuberance of elongated flesh with his flaccid facial tissue” (30). The correspondence between Loy, Julien Levy, and Joella Levy, involving Loy’s representation of Dali can be found in the Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, Box 1 (Correspondence) and Box 9 (Carolyn Burke Correspondence 1999-2004).

- Jessica Burstein writes that “Anxiety about copying had led her to copyright her lamp designs, and later it would cause her to record the origin of her inventions by a variety of emans ranging form the official to the inventive.” (191). She sums up: “The marketplace, riddled with copies, was both threat and promise for Loy” (196).

- Loy favored the “Porte de Cognancourt flea market” (Burke 338).

- For excellent discussions of Loy and fashion see Jessica Burstein, Cold Modernism; Susan Dunn, “Fashion Victims: Mina Loy’s Travesties” , and “Mina Loy and Fashion” in Mina Loy: Women and Poet; Linda Kinnihan, Mina Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography.

- Burstein makes the important point that Loy often used one aspect of her art to comment on her designs in a different medium, as in her painting “Making Lampshades” (190). Burstein asserts that the resemblances between Loy’s hats, lampshade, and dress designs are no coincidence (190).

- See Burke 339. More information can be found in the Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778, Box 6. Folder “Brown, Susan. Correspondence regarding Mina Loy and ‘Jaded Blossoms.’ 1978.”). In summer 1925, Loy’s portraits of Assagioli, Marinetti, Papini, and Stein were exhibited in a Long Island gallery and were sold; they too have been lost.

- Burke notes that Loy sold the Pipes of Pan design but the Helena Rubinstein company changed the name to Syrinx. I haven’t been able to locate a perfume called Syrinx. However, a Helena Rubinstein perfume bottle dated ca. 1948 called “Command Performance” has a structure possibly modeled on glass cigarette containers like those Loy describes in her design.

- This letter is located in the Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 788, Box 1, Inventions.