A Satire of the Avant-Garde

In The Pamperers, Loy turns her attention from the sex war to the avant-garde. Written between 1915 and 1917 and published in The Dial in 1920 for an audience of avant-garde enthusiasts, The Pamperers is the play in which Loy most explicitly addresses the avant-garde artist’s relationship to audience, depicting it as one of cooptation by an art economy rather than control of art consumers. As Jeffrey Twitchell-Waas observes, the play is “directed broadly at an avant-garde that allows itself to be patronized, sanitized, and co-opted by the very class it set out to undermine.”1 The Pamperers satires the avant-garde by exposing its collusion with bourgeois commercial culture.

Siobhan Scarry, who directed a 2010 staged reading of The Pamperers, emphasizes the play’s metatextual dimensions. She classifies The Pamperers as “poetic drama,” drawing from Sarah Bay-Cheng and Barbara Cole’s definition:

plays that draw attention to themselves as literary creations that are never subsumed into the apparent reality of the play. Thus, the textual form of the poetic drama is always self-consciously evident, even in performance.

The self-conscious, metatextual attention to language encourages the audience to be more conscious of their role in the performance. “Loy enacts a constant staging and restaging of language,” Scarry explains, “she never lets the audience, or the readers for that matter, experience language as a transparent medium—it is always present,” and always performative.2

Read the play or scroll down to the summary

Summary

Siobhan Scarry offers this concise summary:

an avant-garde artist… who makes art from cigar ends is seduced and allows himself to be seduced into complete bourgeois co-optation. The play takes place in a salon, presided over by Diana, who is not averse to using her feminine wiles to enact this transformation of the loony into a bourgeois puppet.3

The Pamperers erodes the lines between art makers (geniuses), collectors (patrons and hostesses), and consumers (audiences), all of whom are players in the same commercial enterprise.

The Theater of the Avant-Garde

As in her other plays, Loy “breaks down the barriers between dialogue, scenery, and stage direction” (Schmid 4), but in The Pamperers, she also blends characters and audience into the textual mix. At the play’s opening, the cast of characters merges with objects in the salon setting, “Picked people melted by a distinguished method among the upholstery.” The opening lines are a montage of “Tag Ends of Overheard Conversation,” beginning with the meta-theatrical observation, “The social fabric is a curtain.” Whereas an ongoing conversation establishes the setting in Sacred Prostitute, here, the bits of conversation actually constitute the set. All social discourse, Loy suggests, is performative, and the characters literally materialize out of the fabric settings and fabricated conversations that surround them.

Loy’s interest in female fashion and self-fashioning is evident in one of her paintings from this period, which depicts her original dress designs:

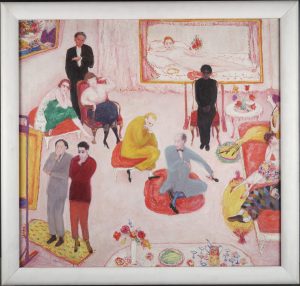

As Susan Gilmore points out, “talk, or gossip, introduces us to Loy’s heroine”; indeed the stars emerge from the celebrity gossip about them, their roles not so much performed for admiring audiences, but produced by those audiences.4 The characters emerge from the public discourse about them. We learn about the Loony, the genius who collects cigar butts, and Diana, the hostess who collects geniuses, long before they appear on the stage, as “Somebody” gossips about them with “Somebody Else.” In this way, the scene resembles an earlier Stettheimer painting, “Soiree,” which similarly embeds recognizable figures from the art world in a highly theatrical tableau:

In Stettheimer’s painting of the New York avant-garde, as in Loy’s plays, life doesn’t merely imitate art, it blends into it, as the woman reclining on the divan in the painting has the same languid posture as those outside it. Art doesn’t merely reflect the social world: it produces society in its own stylized image.

The Work of Genius

When the genius-finder Ossy tells Diana about his latest avant-garde discovery, their conversation makes the work of the culture industry explicit:

OSSY: Di… if you half guessed what I’ve caught in the stables, you’d throw futurism to…

DIANA: Don’t mean…that I’m out of fashion again

OSSY: Since 1 P.M… dispensing entirely with the middleman, we now have the genius served directly to the consumer

DIANA: Let us consume…

High culture is exposed as commercial culture, as art collectors feed consumers’ appetites for the latest fare.

When Loony is served up to Diana, her interactions with him humorously highlight the gendered logic that governs the avant-garde and limits women’s participation to pre-scripted roles. Diana first assumes the role of “backlit muse,” attempting to dazzle Loony with gemstones and seduce him with feminine wiles and felicitious wordplay (Gilmore 288):

I am the elusion that cooed to you adolescent isolation, crystallized in the experience of your manhood… I know the moment to press the grape to thy lip…put ice on your head; for I am the woman who understands.

Loy’s ingenious neologism “elusion” fuses the words “elision” (deletion), “elude” (escape), “illusion” (fantasy), and “effusion” (gush) in the quintessential expression of femininity. But Loony proves impervious to Diana’s feminine charms, refusing to take her with him to “the Grand,” because, he claims, she would have no place in the “Fraternity”: she would be “slighted,” “criticized,” and “considered soft.” Here, the avant-garde is exposed as a male field, closed off to women.

Although Loony denies Diana access to the grand realm of genius, he does escort her to the window to see “The Grand,” effectively inviting her to join the audience for his artistic performance. From this vista, he declaims a futuristic free verse poem that exalts his own creative prowess and scorns his audience’s narrowly confined bourgeois sensibilities. In the midst of his declamation, he asks his implied audience of unperceptive Philistines, “what have you to find/Where can you pick things up?” At which point, Loy inserts this stage direction:

(Diana indicating an ash tray, he reverently pockets half a manilla.)

The stage direction is significant because it points to Diana’s keen-eyed perception. She is, it appears, a more adroit collector of cigar butts than he. Yet, though we see Diana’s genius, Loony remains oblivious to it.

Prohibited from joining Loony on the Grand as a full-fledged artist, Diana continues to try to win him over, resorting to a role that is readily available to her: “precocious trump.” But when her striptease fails to arouse him from his drowsy slumber, she summons her male assistants, commanding them to take Loony to the bathroom and dress him in a new costume.

When he returns from “The Immersion,” he proves amenable to her will, and she instructs him on the proper decorum for a genius:

Stand up—Sir—and dress your soul for dinner. Throw out your chest… Those tirades about the Grand are the thing… dock them up a bit… muddle people up more… But when you’re not holding forth you must be like us… you (hypnotically) are like us…

Diana succeeds in transforming the avant-garde artist into a performer and luring him into the business of selling himself to a gullible bourgeois audience. The mysterious off-stage immersion shifts the power dynamic, stripping the male artist of agency (and clothing) and transforming him into a puppet controlled by a female profiteer.

It’s possible to read The Pamperers as a satire of male Futurist performance, in which a wily female genius beats them at their own game. Jane Lyon offers this interpretation, arguing that the play “suggests that some women are equipped to be better Futurists than men. …In Loy’s play, the woman is the artist, while (male) ‘geniuses’ are merely the readymades (the cigar-butts, as it were) with which artists like Diana work.”5 But Diana has no more mastery of the system than Loony: she must work within the female roles available to her. Rather than achieving access to “the Grand”—that seemingly limitless realm of artistic creation—she, too, remains trapped in a grand commercial scheme to sell the latest art to consumers who are dazzled by anything new.

Through the character of Diana, Loy implicates herself in her parody of the avant-garde. As Sarah Hayden puts its, “By parodying the means by which artists are mediated and manipulated by third parties, ‘The Pamperers’ both reflects on the commodification of Loy’s own artist persona and bears witness to a tendency…for the author to admit (and encode in her writings) complicity with the objects of her critique.”.6 She does not position herself above her audience or outside her scorn. This recognition of complicity is a characteristic en dehors garde gesture: Loy is both outside and inside the logic she critiques. As Linda Kinnahan points out, “Loy’s awareness of her own complicity…suggests a self-perception that alternates from Futurist haughtiness and Dada parody, rendering her en dehors viewpoint complexly aware of the hierarchies embedded in any act of framing, selection, and representation” (“Firenze is a Woman“).

Loy’s Eclectic Method

As in Two Plays and Sacred Prostitute, Loy adopts an eclectic method in The Pamperers, combining avant-garde and popular forms such as burlesque, addressing serious questions with comically absurd effects, and producing an original, disconcerting blend. The cast of characters and setting resemble a Futurist words-in-freedom poem more than they evoke a physical context:

Similar to Marinetti’s Futurist poems, the two-column arrangement of words blurs the line between verbal and visual art. Loy arranges adjectives and nouns irregularly, inviting us to read spatially and generate different permutations: is the Obvious Invisible, or are People Invisible, Obvious and Picked? Is Loony Houseless or are Obvious People Loony? The subsequent paragraph comprises a montage of mismatched, oxymoronic objects and descriptors, ranging from “porcelain breath,” to “Gilded crimson,” “Tailored muscles,” and “Ooze.” The prose poem materializes as a setting from which the characters gradually emerge. “Tag Ends of Overheard Conversation” launch the action with a verbal montage that might best be achieved in a film or audio recording. The technique resembles the transcript or “sonograph” that Loy published in The Blind Man (for a discussion of Loy’s Dada experiment in conversational montage, see “Adagio“).

Perhaps the most en dehors garde aspect of the comical plot that unfolds is the occasional, odd stage direction, such as “(Diana’s chameleon rattles her emeralds.)” or “Picked People evaporate.” The strangest stage direction occurs just Loony mentions his pub companions, “God Gives” and “the Devil to Pay,” who prove to be “one and the same” (70). At this point, Loy directs:

(The room fills rapidly with the Loony’s curiosity, the ‘taken for granted’ advances to audience gravenly noticeable.)

A graven image is an object of worship, usually carved in wood or stone. Loy’s syntax is strange, but the dependent clause seems to apply to Loony, describing his attitude toward the audience. Presumably, he takes for granted the audience’s attention, and his advances to them are “gravenly noticeable” because he carves himself out as an object of their worship. But while the syntax can be parsed, the ideas remain difficult to stage. Loy seems to be anticipating surrealist film techniques that move from external reality to internal states of mind. It is as if, in writing the play, she simultaneously looks backward to medieval and Biblical references and forward to the future of film and surrealism.

Such strange effects are offset by familiar elements of burlesque, like the repeated strip tease, first performed by Diana and later by Loony. In this way, The Pamperers both challenges the audience with intellectual provocations and indulges us with erotic spectacles. But even as she arouses and indulges sexual appetites, Loy defies the conventional gender script. Diana’s fate is very different from that the of the artist’s model in this much more conventional 1903 American silent film, The Fate of the Artist’s Model:7

The film depicts the classic cautionary melodrama of a fallen woman who is seduced by an artist. The fully clothed embrace in the third act is a synecdoche for a sexual encounter. In the fourth act, the woman returns, her white dress replaced with black, signaling her loss of virginity. Her symbolic deflowering is fully realized in the form of the infant she cradles in the fifth and final act. Spurned by the artist, she and the infant are left to the mercy of the elements—and the charity of a working class woman who takes them in.

In the conventional plot of Fate of the Artist’s Model, the woman is a victim of circumstance, limited to the options of what Loy describes in her “Feminist Manifesto” as “Parasitism and prostitution — or negation.” Loy attempts to outwit these gender conventions in The Pamperers. Her heroine Diana tries out the roles of model, seductress, and prostitute, ultimately becoming a madam or procuress who, though she can’t escape the sexualized economy of the art world, can at least profit from it. In this way, Loy’s en dehors garde play choreographs a series of strategic poses, showing how a female artist can work from the margins in an effort to gain greater insight and purchase on central, defining norms.

Courting a Wider Audience

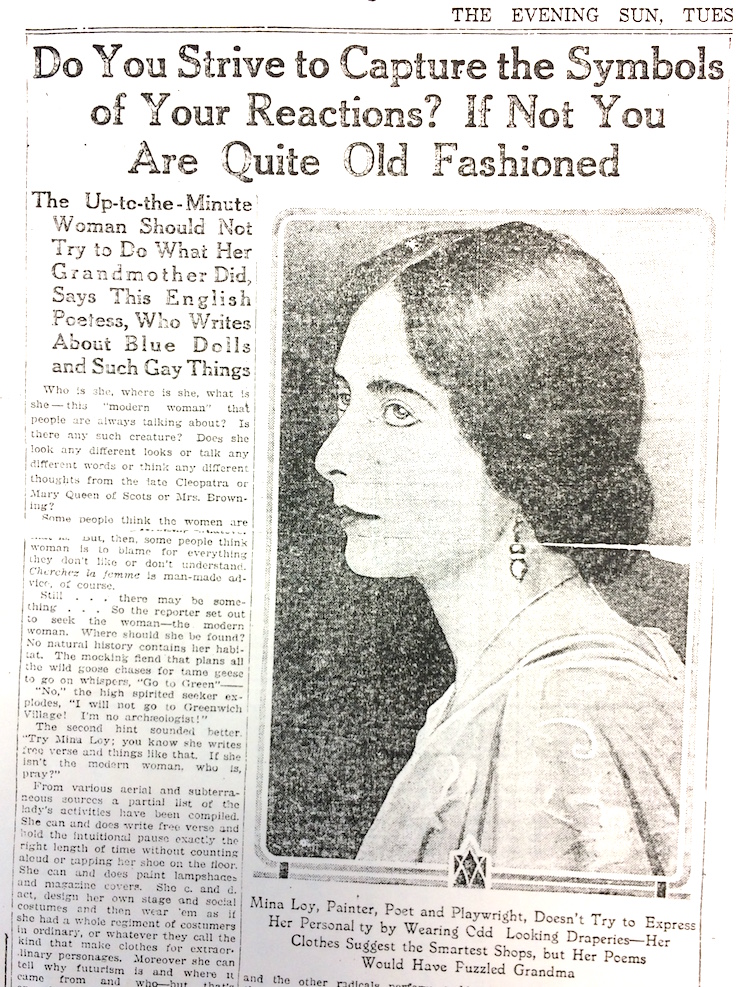

Loy began writing The Pamperers in 1915, while living in Italy, and once in New York, she used the play to court the press, referring to it in a 1917 The New York Sun interview: “she has seen so many movements rise and fall that she has decided to imitate one herself…The play is called ‘The Pamperers.’ It satirizes the Vitalists and the unvital sort and everybody,” the article reports, suggesting that no one escapes the satire. Loy also expresses unbridled enthusiasm for her new city of residence, saying, “No one who has not lived in New York has lived in the Modern World.”

The Pamperers marks a period of transition in Loy’s life, when she puts her combative relationships with the Italian Futurists behind her, and moves to New York in search of both personal and professional fulfillment. The idea of moving to New York had been tantalizing her for years. “I’m rather blue—I’ve seen P[apini] again & I’m frightfully in love—& he hates me with a voluptuous and exotic frigidity,” she wrote Mabel Dodge in 1914, “I do want to run away & come to New York” (qtd by Burke 181). In December, she lamented her disaffection to Van Vechten, asking, “Oh Carlo do you think there is a man in America one could love” (Burke 182). By the summer of 1916, she complained that she was “so tired of Florence that I hardly ever go outside my door” (Burke 192); her poems had been spurned by Amy Lowell, but when she gave them to “ultra respectable elderly ladies (not the stupid ones of course),” she noted, “they survive magnificently—will America be so very different?” (Burk 193). She sailed to New York in 1916, seeking both romantic fulfillment and a public who would embrace her work.

New York proved to be an amorous environment. She found herself in the proto-Dada set that centered in Walter Conrad Arensberg’s studio on West 67th Street, where Marcel Duchamp was a primary agent provocateur. “An instantaneous affection was fashionable,” Loy recalled, “One heard little less than exhortations to love” (qtd by Burke 219). But rather than joining the amorous intercourse, Loy observed the theatricals from a distance: “I watched the men cooing the assertively ‘modern’ women into the nests of their astringent lusts, to crush them ‘tomorrow’ in the contracting pupils of their observant eyes” (Burke 219). Loy viewed the free-loving New York set as a “marionette theatre” in which “interchangeable actors and audiences played into each other’s hands” (Burke 219). (For more on Loy and New York Dada, see “Pas de Deux.”)

The Pamperers puts the “marionette theatre” of the international avant-garde art world on stage and subjects it to en dehors scrutiny. Indeed Loony’s latest artistic innovation—collecting cigar butts—seems to have as much in common with Duchamp’s Dada invention of “readymades,” as with Marinetti and Papini’s Futurist polemics and performances.

Representing the Avant-Garde in The Dial

Appearing in The Dial, in the company of Arthur Rimbaud, James Joyce, Ford Maddox Ford, André Derain, and Babette Deutsch, Loy serves as a representative, spokesperson, and interpreter of the international avant-garde. The Pamperers, chosen to inaugurate the “Modern Forms” section of the magazine, represents the quintessential avant-garde form. Although Hayden argues that Loy’s “processual theorizing” of the avant-garde “barely registered in the instant of their production and partial publication” (Hayden 4-5), the positioning of The Pamperers in the Dial, like the publication of “Cittàbapini” in two separate installments of Rogue, suggests that little magazine editors and their readers were not only cognizant of Loy’s power as avant-garde interpreter, but also hungry for her sharp wit and perceptive insights.

In his “Foreword” to “Modern Forms,” distinguished art critic Henry McBride doesn’t mention The Pamperers, but he discusses the very problem the play raises and stages: how to evaluate new, experimental art—both how make sense of it, and how to assess its value. McBride is especially concerned with the question of how to distinguish authentic new art from frauds and hoaxes.

Situating Arensberg’s “exclusively modern” studio as the hub of the New York avant-garde, McBride offers “Marcel’s latest”—a hermetically sealed vial of air from Paris—as a case in point. McBride contrasts his enlightened understanding of Duchamp’s readymade to the befuddled reactions of a “friend” with conventional, bourgeois tastes. Whereas the friend deems Duchamp’s so-called “art” incomprehensible and highly suspicious, McBride finds it “pleasant and droll”: “Perhaps I instantly saw the joke did not apply to me so much as my educated friend,” he explains, “That’s the advantage in not being a bourgeois yourself.”8 His remark suggests that the avant-garde mocks bourgeois audiences, satisfying the tastes and sensibilities of an intellectual elite—a superior class status that he implicitly inhabits with readers of The Dial.

Ironically, even as McBride emphasizes his and his readers’ distinction from the bourgeois, he addresses them as would-be art collectors, offering advice about how to become more sophisticated consumers of art: “My own recommendation… is—to know a ‘modern’ artist” (McBride 63). He thus trains readers to become consumers in the capitalist economy of avant-garde art that The Pamperers proceeds to satirize.

Although McBride’s attitude toward bourgeois audiences is more dismissive than Loy’s, his “Foreword” may not actually be at cross-purposes with her play. After all, both attempt to generate interest in avant-garde art. The Pamperers does not aim to warn us out of a phony art market, but to get us in on the joke and to make us recognize that we are all in on the sham—artists, wealthy collectors, and bourgeois audiences alike (“you must be like us… you (hypnotically) are like us…”). In this way, Loy trusts that her audience—unlike the trend-chasing art consumers in The Pamperers—will be cunning enough to recognize the sham, even if they, like her, cannot extricate themselves from the market.

- Jeffery Twitchell-Waas, “‘Little Lusts and Lucidities’: Reading Mina Loy’s Love Songs,” Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, Maeera Schreiber and Keith Tuma, eds. Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation, 1992. p.113.

- Scarry, Siobhan. “Introduction,” Poets Theatre Production: The Pamperers, Open Space Gallery, Victoria, B. C.. Nov. 12, 2010, p. 1.

- Scarry, “Introduction,” p. 1.

- Susan Gilmore, “Imna, Ova, Mongrel, Spy: Anagram and Imposture in the Work of Mina Loy,” Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, Eds. Maeera Shreiber and Keith Tuma, Orono, ME: The National Poetry Foundation, 1998, 271-318.

- Janet Lyon, “Mina Loy’s Pregnant Pauses: The Spaces of Possibility in the Florence Writings,” Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, p.397.

- Sarah Hayden, Curious Disciplines: Mina Loy and Avant-Garde Artisthood, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2018, p.8.

- Robert Quesinberry, 1903 Silent Movie – The Fate Of The Artist’s Model – Biograph, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GjtUoqUkt5Y&feature=youtu.be, Accessed 14 Mar. 2019.

- Henry McBride, “Foreword” to Modern Forms, The Dial 69.1 (July 1920),p.62.