Published in the August 1915 Rogue, Loy’s first Two Plays—”Collision” and “Cittàbapini”—take up only a page and a half in their entirety. Each can be read or performed in less than five minutes—though making sense of them could take considerably longer. Composed in disjunctive, telegraphic language, the plays read more like narrative descriptions of dramatic action than actual scripts. There is almost no dialogue, and the stage directions blend with the settings, characters, and action, much of which is abstract and cerebral.

Read the plays or scroll down to plot summaries

Plot Summaries

In “Collision,” a man, shut in a large hall, proclaims that isolation and emptiness are necessary precursors for creation. He presses a button, and the hall erupts in a cataclysm of noises, lights, convulsions, and explosions. As the chaos intensifies, the man relaxes and announces that the vibrations have reached the intensity required for each individual to self-actuate. The vibrations accelerate until the man stiffens and silence ensues. After a brief pause, a tremor arises to restart the cycle. “The curtain falls,” concluding the drama. Actually, in Rogue, “the curtain falls” twice, as if to underscore the repetitive nature of the cycle. But this is likely a printer’s error, since in Loy’s typed manuscript, “the curtain falls” only once.1

3D animation of Collision,

created by Leah Mell, Davidson College, Class of 2019

To read more about Mell’s animation of “Collision,”

navigate to New Frequencies: “Loy’s ‘Collision’ – 3D Animation”.

Scene 1 of “Cittàbapini” depicts a temporally compressed, 24-hour game of copycat between “a greenish man” and “the city.” At noon, the man stares at the city, which stares back; in the evening, he smiles, and the city laughs back; in the morning, he mocks the city, and the city swallows him and then spits him back out. He berates a woman for not being a man and grumbles about a man’s resemblance to himself. He then climbs a mountain, which shakes him off, sending him rolling down into the city. “The curtain falls in the mud.” In Scene 2, the city sleeps, while the man, wielding a pen and manuscript, attempts to write himself over the city. He is washed away by the river and subsumed by the sun, which burns up the city. “The curtain does not fall,” and Two Plays concludes with a reference to the date and place of its composition: “February 28, 1915, Firenze.”

Parodies of Futurist Performance

Loy uses parody, a form of mocking imitation, to ridicule the performative attitudes and behaviors of Futurist men through condensed, exaggerated mimicry, while amusing audience members who presumably get the joke. In “Collision,’ the lone performer who aligns himself with machinery resembles Marinetti, whereas the title “Cittàbapini” (City of Bapini) and “greenish man” allude to the green-eyed Papini. In both plays, the joke is on Futurist Man. The main character is an artist who expresses contempt for the public and performs for his own satisfaction and self-aggrandizement. In “Collision,” he bangs the door shut to isolate himself in the act of “CREATION.” In “Cittàbapini,” he taunts the city, execrates passers-by, and declares, “I am not—unless—disparate to the neighbors—I am—to prove myself unique—“ While Futurist Man achieves an artistic apotheosis in both plays, he proves to be neither autonomous nor supreme. He is ultimately subsumed by elemental forces beyond his control, whether mechanical (“Collision”) or natural (“Cittàbapini”). The Futurist artist proves to be the object rather than the orchestrator of the creative process.

Loy’s Eclectic Method

In these early, experimental micro-plays, Loy develops an eclectic method that blends elements of Futurist theater, cinematograph, and puppet theater. This method exemplifies the en dehors garde in its strategic blending of avant-garde and popular forms.

Futurist Theater

As Julie Schmid points out, Loy deploys the themes and aesthetics of Futurist theater to parody Futurist performance: “Two Plays exemplifies futurist theatre in their use of lighting and kinetic scenery, as well as through their innovative use of language.”2 Loy’s disjunctive language draws upon Marinetti’s notion of words-in-freedom, “in which syntax is destroyed and words are used ‘telegraphically’ in order to ‘assault your nerves with visual, auditory, olfactory sensations’” (Schmid 3). Set design and stage directions dominate the scripts, reducing the significance of the characters. “Dwarfed by scenography made up of colliding planes, lights, mountains, and city scapes, the sole character, Man, becomes incidental in both performances” (Schmid 4).

“Collision” could be staged on a set like this Cubo-Futurist design, with stagehands hiding inside large geometric forms, moving them erratically, as spotlights flash about the stage, and dissonant sound effects add to the confusion. But while Loy’s cartoonish micro-dramas incorporate Futurist themes and aesthetics, the animated sets, simple plots, and crude caricatures also suggest the influence of the popular traditions of cinematograph and puppetry.

Cinematograph

Cinematograph, an early form of film and animation, was first developed in the 1890s, and by the 1910s had become a popular form of entertainment in European cities including Florence. In a 1913 letter to Mabel Dodge, Loy mentions going to the cinema, and in a 1914 essay “On Futurismo and the Theatre” in The Mask, Gordon Craig boasts that he goes “very often to a Variety Theatre and to the Cinematograph.”3 Carl Van Vechten also reports stopping to watch an “exhibition of moving-pictures” in the Italian town of Arezzo en route to Vallambrosa with Loy and several other expatriots in July 1914 (qtd by Kinnahan, “Italian Retreats“)

Early cinematograph productions deploy visual effects and planetary tropes similar to those enacted in Two Plays, in which settings become animate and planets take on human characteristics. George Méliés famous Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) depicts live actors climbing into a torpedo-shaped spaceship, which is launched into the sky, where it strikes a cartoon face of the moon in the eye. Here is the scene of the launch:4

Robert W. Paul’s short 1906 film The Motorist uses similar visual tricks, combining live actors and animations, as well as mechanical and natural elements. As in Two Plays, the visual effects defy the laws of physics and toy with perspective and proportion:5

Whether or not Loy saw these specific films, the animation technologies had been well established by the mid-teens, and she might have been thinking about such “magical” cinematographic effects when she wrote the seemingly impossible stage directions for Two Plays. “Collision” calls for “shafts of light [to] crash through fifty-nine windows” and “the floor [to be] worked by propellers.” These are difficult effects to achieve in a small, low-budget experimental theater like the Provincetown Players, but might more easily be accomplished through cinematographic animation. The Man could merge with his mechanized surroundings, much as the driver of the car gets swept up into the heavens in The Motorist.

Similar special effects could be used to animate the city in “Cittàbapini,” allowing a set of buildings to laugh, swallow, and then spit out the “greenish man.” He could ascend the mountain, much as the car drives up the side of a building in The Motorist, a dramatic shift in proportion and perspective allowing him to write with his “stylograph” across the face of the city. At the end of the play, the greenish man could “drop a tear into the river” and be washed away by it and then “received” up into the sun using animation techniques similar to those used when the spaceship pierces the eye of the moon in La Voyage dans la Lune, releasing drops of blood or tears.

Puppet Theater

The comic violence and antagonistic relationship between characters in “Cittàbapini” also calls to mind the tradition of puppet theater, which Loy would have been exposed to from an early age. Growing up in London, she would likely have seen Punch and Judy shows such as this one (lincolnshireecho):

The folk tradition of Italian puppetry was also readily accessible in Florence. Gordon Craig published the multi-installment “History of Puppets” by Yorrick [P. Ferrigni] in The Mask in 1913, which reported “more than four hundred Marionetti ‘edifizi,’ large and small, on Italian soil” in 1884, and more than 40-thousand “burattini” (hand puppets) in 1913. Roving companies staged puppet shows in public plazas and theaters across the country, including in Florence (27-8). If Loy did not see one of these performances, she most likely read about them in The Mask.

The simple, comical plot of “Cittàbapini,” with its crude, violent caricatures, evokes traditional Italian puppet shows like this one (CarroDeiComici):

Loy’s play could be staged in a similar small puppet theater with “marionetti” or “burattini” performing the roles of the “greenish man” and passers-by. Small scuffles could break out when the greenish man “execrates” a passing woman, saying “You are not a man,” and then scowls at a passing man, grumbling, “horrific resemblance to myself.” The city buildings and sun could come to life as violent, voracious puppets that devour, spit out, and sweep up the human puppets.

Whereas Futurist theatrical techniques aim to alienate and defamiliarize an audience, cinematograph and puppetry seek to amaze, entertain, and amuse. And whereas Futurist performance breaks the fourth wall in order to assault and antagonize the audience, part of the pleasure of cinematograph and puppetry comes from the audience’s awareness of the film director or puppeteer behind the scenes—the off-stage genius who has designed the spectacle for their amusement.

By combining Futurist techniques with elements of cinematograph and puppetry, Loy attempts to convert an alienating theatrical experience into a jovial, collaborative relationship between artist and audience. Two Plays are parodies of Futurist performance, and parody is an inside joke that relies on mutual understanding and recognition—it is a collaborative form.

Courting an Audience in Rogue

Readers of Rogue—a sophisticated coterie of avant-garde enthusiasts—would have been receptive to the parody, and Loy was just as receptive to them, devouring every copy of the magazine she could get. “I long for news of what all the Rogue people & so on are doing,” she wrote to Van Vechten, beseeching him for the latest editions. Her eagerness suggests that she thought of the “Rogue people” as kindred spirits who would provide a sympathetic audience for her plays.

The juxtaposition of Two Plays with an invitation to subscribe to Rogue suggests that the imagined kinship between author and readers was mutual. The editors assumed Loy’s plays would stimulate their readers’ appetite for more experimental writing from abroad. The date and place of composition—“February 28; 1915, Firenze”—highlights Loy’s position as a representative and translator of the European avant-garde. The time/space coordinates also link her cutting-edge cosmopolitanism to the project of the magazine, which provides its own parallel coordinates, 149 West 35th Street, New York City, in the subscription ad below.

The subscriber is given blanks to fill in “Name,” “Town or City,” and “State (if necessary),” the implication being that Rogue readers should come from a metropolis large enough to need no further explanation. Thus, author, magazine, and reader, no matter how far flung, are brought together within an intimate, cosmopolitan community of those “in the know.”

Readers of Rogue would likely recognize the Futurist targets of the parody in Two Plays. As Jessica Burstein argues, “the magazine is so much a series of inside jokes…and so thick with contradiction, emendation, and self-referentiality that it demands being read, not just ‘cover to cover’ as one of the advertisements suggests, but from one issue to the next.”6 The coterie audience would have read Loy’s poem “Sketch of a Man on a Platform” in the April issue and discerned the outline of Marinetti, a “Man of absolute physical equilibrium,” whose “force,” “movements,” and hostility to the public bear striking resemblance to the Man in “Collision.” They could be relied on to detect an allusion to Papini in the title, “Cittàbapini,” and be amused when “Giovanni Bapini” reappears on the Rogue stage in 1916, starring in Loy’s poem, “Giovanni Franchi.”

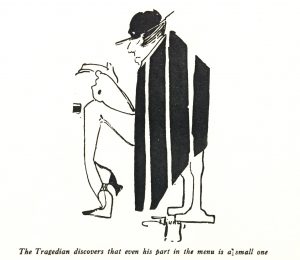

Loy adopts an eclectic, en dehors garde approach to theatre, combining avant-garde and popular forms with personal references and inside jokes, in order to entertain her audience with parodies of Futurist performance. Two Plays positions the audience at a critical distance from Futurist performance that allows us to enjoy the spectacle of the creative act, even as we laugh at the antics of the arrogant male artists. These characters think that they have orchestrated a “magnificent spectacle,” but Loy’s clever staging shows us that they are the puppets and not the producers of the plays. Like the Tragedian in Djuna Barnes’s drawing (below), Loy’s plays show that the Futurists parts in the drama are much smaller than they’d like to believe, while the audience’s role is much greater.

- Julie Schmid interprets the repetition as deliberate, arguing: “these stage directions indicate that the process is about to begin again, and at the end of the play the repetition of ‘the curtain falls—the curtain falls,’ subverts the conventional dramatic action of closure or resolution: what occurs isn’t a singular process but, rather, a repetitive cycle of which the play records a mere fragment” (4).

- Julie Schmid, “Mina Loy’s Futurist Theatre,” Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Jan. 1996), p.3.

- Gordon Craig, “On Futurismo and the Theatre: Some Notes,” The Mask 6:3 (Vol. 6, No. 3, Jan. 1914, 195), 194-200.

- TheParmaViolet, “Le Voyage Dans La Lune” George Méliès 1902 (Original Version, Silent and Black & White), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9m830jhUi3E&feature=youtu.be, Accessed 14 Mar. 2019.

- Iconauta, Robert W. Paul: The Motorist (1906), YouTube, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/69/The_%27%3F%27_Motorist_%281906%29.webm, Accessed 14 Mar, 2019.

- Jessica Burstein, Cold Modernism: Literature, Fashion, Art, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012, p.163-4