But the Play Goes On

Loy’s plays have been considered Futurist plays, and each in various ways takes up Futurist themes, aesthetics, and performance techniques. But with concerns much larger than Futurism and influences far wider, Loy’s plays are better understood as en dehors garde experiments. Collision and Citabapini are the most Futurist of the plays, utilizing Futurist techniques to depict artist figures at war with their audiences and environments, while parodying their attitudes and behaviors. In Sacred Prostitute, Loy shifts her attention to the relationships between women and men, investigating whether the romantic Love and the genius Futurism can form a mutually fulfilling partnership. The very fact that Loy casts “love” as a woman and “genius” as a man shows how much gender conventions are built not only into heterosexual relationships, but into our conceptions of romance and art. Love, an emotional bond, is understood as a female prerogative, whereas genius, an intellectual and creative faculty, is deemed a male capacity. In The Pamperers, Loy turns her satirical eye on the avant-garde art world. While she continues to explore artistic performance, genius, love, and gender conventions, she broadens her investigation to examine the economies that fuel artistic and sexual exchanges.

Whatever topic she takes up, Loy is always interested in courting an audience. Her plays provide a record of her evolving understanding of the artist’s relationship to an audience. In Two Plays the Futurist artist must turn away from the social world to the natural elements to achieve his artistic apotheosis: characters merge with kinetic settings to become part of a larger creative process. But in The Sacred Prostitute and The Pamperers, there is no turning back on an audience, and no way out of the performance. Loy attempts to write her way out of prefabricated scripts by casting male Futurists as lovers and muses, and female muses and hostesses as artists and geniuses. What her plays ironically reveal, however, is that artistic geniuses, whether male or female, are caught in the same game: though they may be dealt different hands, they get caught up playing by the same gendered rules. And the players prove to be no different from the audience: whether seducing or watching the seduction, they are all invested in the same cultural enterprise.

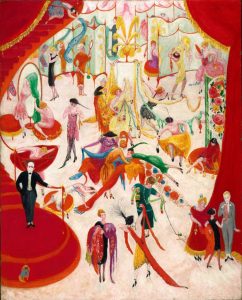

Loy’s plays depict mass culture as a heterosexual economy—a culture industry intent on perpetuating itself and preventing even the most futurist women and men from rewriting the script. As in Florine Stettheimer’s 1921 painting, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, Loy exposes the entanglement of art, theater, and commerce, all of which blur together in a hall of mirrors:

Subsumed within the spectacle, men and women, actors and audiences, creators and consumers all participate in the same economy. To climb the staircase is only to fall with the curtain: the spectacle encourages our eyes to repeat the same cycle, circulating within the scene.

The nascent theory of the avant-garde executed through Loy’s plays is expansive and visionary precisely because it includes gender—a crucial component overlooked in seminal theories of the historical avant-garde ranging from Clement Greenberg’s 1939 “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” to Peter Burger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde (1974, 1980). These theories emphasize the originality of the heroic, individual artist who defies tradition and assaults the sensibilities of bourgeois audiences. In contrast, Loy’s plays wed popular traditions with avant-garde techniques in an effort to entertain and enlighten audiences. The plays embed the avant-garde artist within social settings and commercial markets, demonstrating his dependence on audiences and his entanglement in bourgeois, capitalist economies. In Loy’s theatrical vision, the avant-garde is a social and commercial enterprise, as well as a gendered arena. And no one escapes unscathed, not even the artistic genius—or the audience she depends on.

Composed relatively early in her career as a writer, Loy’s plays represent her nascent outward turns. Experiments with performance, gender constructions, and spectacle, the plays are not only important works in her development as an artist, but also exemplary texts for a theory of the en dehors garde.