Villa Life in the Arcetri

With a Baedeker in hand – a popular guidebook written for English visitors to Europe – arrivals new to Florence at the turn of the twentieth century gained a history of the city. Offering guidance to all manner of services, its information-rich pages instructed the visitor on how to navigate the city and its environs by electric or steam tramways, omnibuses, and cabs; where to find Havanna Cigars or Confectioners or Cafés; the locations of the post office, telegraph office, and British consulates; suggestions for English-speaking churches, physicians, and chemists; advice for the best baths, shops, booksellers, photographs and photographic materials (significant, one would imagine, to Loy’s photographer husband); recommendations for artists and teachers of music and Italian; and information on theaters, festivals, and the flower market.

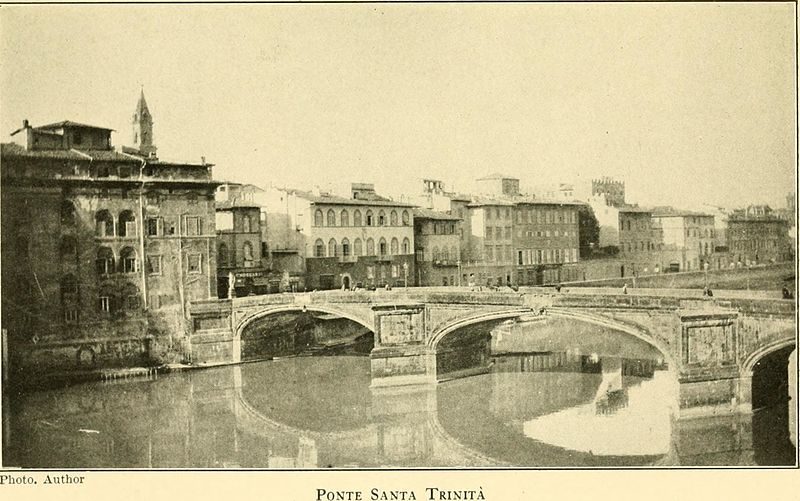

Arriving in Florence in the winter of 1907 with her husband Stephen Haweis, Loy might have unfolded the delicate pinkish and white Florence map inserted in the Baedeker’s copious chapter on the city. Tracing the route from the train station to their new home in the Arcetri hills outside of the city, they could cross the Ponte alla Carraia across the Arno river and take the Via Serragli to the Porta Roma, or perhaps cross the Ponte San Trinita to the Via Maggio and, at the Pitti Palace, head west on the Via Roman to the Porta Roma. From this ancient gate, hilly roads would wind up to their first home in Florence.

At the busy Stazione Centrale Santa Maria Novella, early twentieth-century visitors consulted the Baedeker to find where to meet the “omnibuses” or a “cab,” forewarned that “there is often a scarcity of conveyances” (Baedeker’s Northern Italy 457).

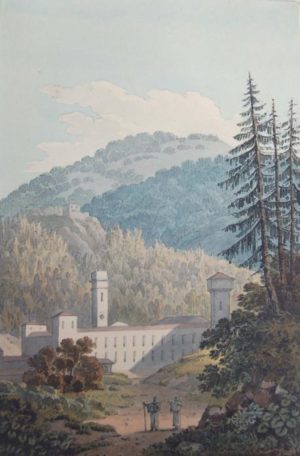

From the station, Loy and Haweis took a horse-drawn carriage to travel through town, southward across the Arno river into the hills, dotted with villas and splendid views high above the city, to arrive in the Arcetri area and their new home, the Villino Ombrellino at #11 Piazza Bellosguardo (Burke 105).

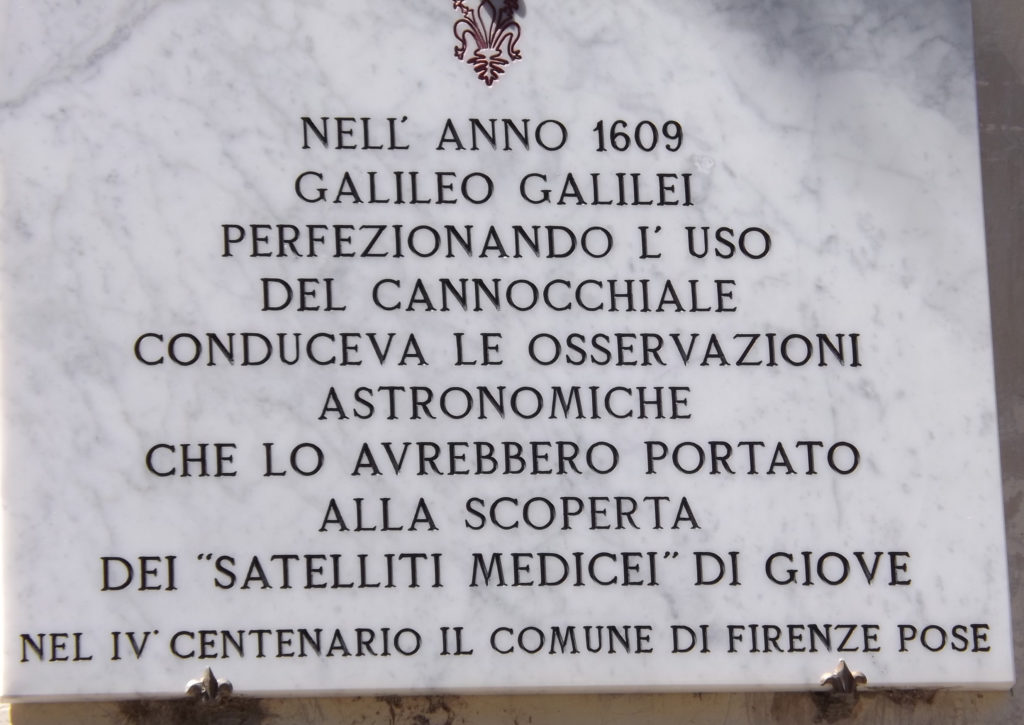

This small villa garners a brief entry in Baedeker’s Northern Italy, 1906, that includes a set of directions and describes its significance as a Renaissance residence of Galileo:

From the Monte Oliveto the Via di Monte Oliveto leads to the S., crossing a small square and passing several houses, to (½ M.) the Piazza di Bellosguardo. Then the short Via Roti-Michelozzi leads to the left to the Villa Bellosguardo, near the entrance of which we obtain one of the finest Views of Florence. Adjacent is the Villa dell’ Ombrellino (formerly Segni), occupied by Galileo in 1617-31, and now marked by his bust. (552)

Pregnant with the child of her lover, Henry Joël Le Savoureux, the Parisian doctor treating her for “neurasthenia after the death of Oda [her first child],” Loy had agreed to move to Florence with her husband to avoid scandal when Haweis agreed to claim the child (Burke 102). As a condition, he demanded that they relocate from Paris to the Villino Ombrellino when a friend offered them her remaining lease for the year, lasting until summer (Burke 104). In Florence, they found an “Italian city with a strong English accent” and a well-populated Anglo-American community (Harold Acton, quoted by Burke 106).

In these first months, at a distance from the city that could feel isolating for the pregnant Loy, the couple – or sometimes just Stephen – began acquaintances with other English residents living in Florence. After several months at the Villino Ombrellino, the couple and the baby Joella moved into a rented apartment in Oltrarno section of the city. Loy found herself amidst the jostling energies of avant-garde invaders in Renaissance-laden Florence.

The Olr’arno / Oltrarno / Across the Arno

A nice walk from the Centro, or city center – beginning perhaps at the Duomo – takes you quickly to the river Arno, where you can stroll along the walls lining its banks on either side. The river Arno cuts diagonally through Florence, and multiple bridges take you across to the Oltrarno. The “Oltr’arno” the Baedeker tells us, is Florence’s “left bank,” a district containing about “one-fourth” of the city (536).The Ponte Santa Trinità lands one near the peaceful domed basilica of Santo Spirito, a Romanesque church begun in 1436. For the most direct route to the Costa di San Giorgio, the hilly street where Loy and Haweis moved, take the Ponte Vecchio, picturesquely lined with shops and often congested with pedestrians and shoppers. The 1906 Baedeker directs visitors to the “quaint and picturesque” Ponte Vecchio bridge, “flanked with shops, which have belonged to the goldsmiths since the 14th century” (Baedeker’s Northern Italy 537, 538).

Stepping from the Ponte Vecchio into the Oltrarno, you will find streets of busy shops, cafés, and restaurants within a few hundred yards of the Pitti Palace and the entrance to the expansive Boboli Gardens. Within a few dozen steps of the bridge, the base of Costa di San Giorgio, the street Loy inhabited for years, begins in the Piazza Felicita. Let us pursue Loy’s traceries through the Oltrarno.

On the Way to the Costa di San Giorgio

Costa di San Giorgio winds upward through the Oltrarno. By spring of 1908, Haweis rented a studio on the street while he and Loy lived in the Villino Ombrellino. On the same side of the Arno as the Arcetri area but a steep descent from the hill-top Villino Ombrellino when coming toward the city (and an arduous hike back up), the studio location likely helped prompt the couple’s subsequent move to the same street later that summer to a rented apartment.

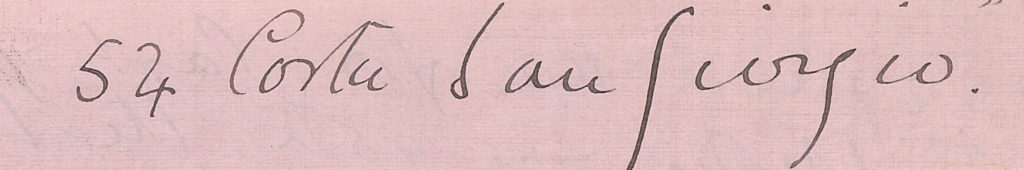

In 1910, Loy and Haweis bought a home at #54 midway up the hilly street, near the Chiesa di San Giorgio, or Church of Saint George. (Florence has subsequently renumbered houses on the street, and Loy’s home is now #60, according to Carolyn Burke, Loy’s biographer, who stayed in the home at one point in her research). They purchased the home with the help of Loy’s father (although, as was customary for the time, the house was in Haweis’ name) and after the birth of both Joella and their son Giles. They transformed the top floor, fronted by shuttered windows, into two studios (Burke 118)

To find Costa di San Giorgio, cross the Ponte Vecchio into the Olr’arno area. One can then turn left soon after the bridge, onto the Via dei Bardi, running just above and parallel to the Arno.

After a short block, a set of steps on the right takes you to Costa San Giorgio. Turn left at the top of the steps and climb the hilly street.

Rather than taking the steps, you can start your climb up the Costa di San Giorgio from its lower origin point. Just after the Ponte Vecchio, cross over the Via dei Bardi (rather than turning onto it) and almost immediately enter the Piazza San Felicita on the left. The Costa di San Giorgio begins at a narrow opening between two buildings in a far corner of the Piazza.

Literary Detour With Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Before you climb Costa di San Giorgio, consider a literary detour to Casa Guidi, the home of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Loy’s Victorian predecessor poet and expatriate. Casa Guidi is a short walk from the Ponte Vecchio, located on the Piazza San Felice (not be be confused, as I was, with the Piazza San Felicita, which one crosses to the Costa di San Giorgio). When you cross Ponte Vecchio to enter the Oltr’arno, continue onto Via de’ Guicciardini (the road continuing straight from bridge). This street becomes the Piazza de’ Pitti as you approach the Pitti Palace. The Piazza San Felice is at the south end of the Piazza de’ Pitti, beyond the Palace. Turn right, and Casa Guidi will be on your right.

Living near the Boboli Garden and Pitti Palace, gazing upon Florentine streets from the windows of her home, Barrett Browning famously penned “Casa Guidi Windows,” a poem written in support of Italy’s 19th-century nationalist revolutions. Imagine Loy strolling past the Casa Guidi, the home of Britain’s famously Italianate Victorian poets, identified by a 19th-century plaque above the door. identified by a 19th-century plaque above the door and by the Baedeker: “No. 9, Piazza San Felice, is the Casa Guidi, in which Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning lived from 1848 till the death of the latter in 1861. . . See her poem, ‘Casa Guidi Windows’” (547).

Standing under the windows Barrett Browning once occupied, an intriguing thought occurs. Might Loy have heeded the Baedeker’s advice to read the older poet’s two-part poem, “Casa Guidi Windows” spoken by a female “I” positioned at the window of her home? A British woman in Italy, Barrett Browning’s poem witnesses the initial stages (the late 1840s) of the Risorgimento in Florence, the unification of Italy that would only be successful later in the century.

Would Loy, the twentieth-century poet, have been struck by Barrett Browning’s deliberate positioning of a woman at the window of her Italian home in the mid-nineteenth century, looking onto the piazza at the tumult and energy of the street? Several of her Italian poems adopt the perspective of women gazing from windows. In these poems, this perspective directs the focus of Loy’s critiques of gender constructions and power dynamics. In “Virgins Plus Curtains Minus Dots” (1914), young virgins “See the men pass” freely on the streets while they linger “behind curtains,” kept in the domestic sphere as “Virgins for sale”:

Somebody who was never

a virgin

Has bolted the door

Put curtains at our windows (LLB96 22)

“The Costa San Giorgio,” one of three poems in “Italian Pictures” (1914), suggests the window view in observing the street below and the “passionate Italian life-traffic” (11). The speaker joins other observers, “Variously leaning” from “the green shutters” to “Mingle eyes with the commotion” (12). The later “Summer Night in a Florentine Slum” frames its speaker explicitly at the window, as her gaze mingles or mixes her others on the street, much as Barrett Browning imagines a connection with her Italian neighbors through their windowed viewpoints:

I leaned out of the window – looking at the summer-strewn street; late in heat – lit with lamps, and mixed my breath with the tired dust.

The dust was hot, the dust was dry – it lay low, it travelled about; and among it, Latin families lay on the lousy stones, in what they could manage of an earthy abandon. (LLB82 81)

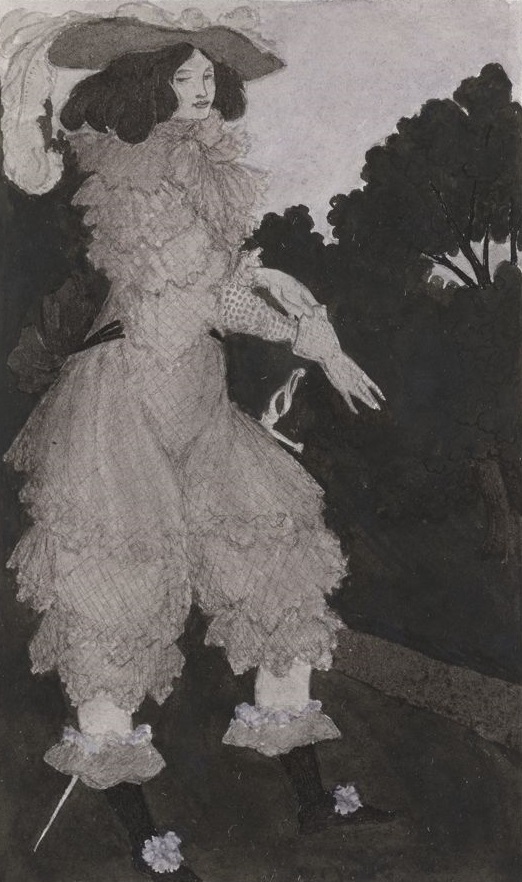

Rather than the view of Italian patriotism, as with Barrett Browning, Loy’s speaker witnesses poverty, sexual aggression, and women’s mistreatment. As the prose-poem ends, the speaker “drew in my head and pulled the English chintz curtains scattered with prevaricating rosebuds.” Her English privilege is both acknowledged and placed under subtle criticism as she finds herself under the gaze of a print of “Beardsley’s Mademoiselle De Maupin [as she] drew on her gloves at me from the wall” (LLB82 83).

The historical Julie d’Aubigny, or Mademoiselle Maupin, a 17th-century woman notorious for her cross-dressing, sword mastery, and opera performances, became the subject of Théophile Gautier’s novel named for her (1835) and Aubrey Beardsley’s later illustrations (1898). The print Loy references shows Mademoiselle in men’s clothing, pulling on gloves and staring directly at the viewer, “at me,” the speaker specifies. Loy might well have been intrigued by Maupin’s masculine performances and their replay in fiction and art; moreover, one can imagine Loy’s bemused appreciation of the adoption of feminine decor and frill in 17th-century masculine attire.

Much as this print plays with gendered conventions, Barrett Browning anticipates the cross-dressing her own poem performs in the eyes of her readers, as she assumes a perspective on politics usually reserved for men. Her gendered viewpoint, located in the domestic space, was indeed suspect at the time of the poem’s 1851 publication. Its preface offers a consoling “Advertisement,” reassuringly stipulating that the poem contains the impressions of the writer upon events in Tuscany of which she was a witness. ‘From a window,’ the critic may demure. She bows to the objection in the very title of the work, disclaiming the poem as anything but a “simple story of personal impressions.” Muting the socio-political – while defiantly personal – project of the poem, these prefacing comments speak to the negotiations of gendered authorship that Loy confronted some six decades later.

From her domestic point of view, Barrett Browning views the lively street “ ‘Neath Casa Guidi windows” in a home located “ ‘Twixt church and [Pitti] palace.” The long poem weaves this perspective through expanding views of the city and its “Bewailers for their Italy enchained.” They stand

upon this shore

Of golden Arno as it shoots away

Through Florence’ heart beneath her bridges four

Bent bridges, seeming to strain off like bows.

Her position at the window links her, as British subject, with the Italian rebels and the populace, “With doors and windows quaintly multiplied, / And terrace-sweeps, and gazers upon all.” The speaker gazes upon a celebratory parade, a momentary victory before frustrating setbacks. All of the house windows are seen as portals to public, political realities, the speaker hailing “How we gazed / From Casa Guidi windows” and how “ hands broke from the windows to surprise / Those grave calm brows with bay-tree leaves thrown out.”

This sense of connection to the Italian cause prompts Barrett Browning to also inscribe the importance of Italy and Florence upon the British poetic tradition. Prominently, “the cup of Milton’s soul” was filled by “Your beauty and your glory,” as Italy garners adulation in Paradise Lost. Milton’s reference to Vallombrosa’s mountain forests (not far from Florence) echoes through Barrett Browning’s long homage to Italy and, whether consciously or not, resurfaces in Loy’s 1914 “July in Vallombrosa” (see Italian Retreats). Standing between Loy and Milton, Barrett Browning praises how the earlier poet

sang of Adam’s paradise and smiled,

Remembering Vallombrosa. Therefore is

The place divine to English man and child,

And pilgrims leave their souls here in a kiss.

As you stand before Casa Guidi, ponder the imagined lineages conjured by this spot. Was “Casa Guidi Windows” a prompt to Loy in writing her own views from Florence windows? Did she remember Milton’s praise as paradise for the mountain resort she visited from Florence (and likely saw the plaque to him there), or the other poets and artists who had earlier visited the Italian mountain top?

These imagined poetic intersections, however fanciful, point to the complexities readable in Loy’s Italian poems and attending her developing sense of herself as a poet. A connection to earlier British poets is both suggested and troubled by Loy’s own poetic focus on places inhabited by her poetic ancestors and the points of view adopted.

For example, Barrett Browning’s imaginative evocations of “Florence wanderings” serve in her poem as a way of enumerating an Italian history justifying the mid-nineteenth century struggle for national identity. Loy, wandering (and writing about) the early twentieth-century streets of Florence, might also recall Barrett Browning’s description of standing in the spot of Loy’s first Florence home, in the “Tuscan Bellosguardo. . . Where Galileo stood at nights to take / the vision of the stars” (“Casa Guido Windows”). Galileo, and then Barrett Browning, gazed upon the stars from Loy’s first home, the “Villa dell’ Umbrillino” in Arcetri. Upon her arrival in Florence, Loy’s Baedeker taught her that her newly rented villa was previously “occupied by Galileo in 1617-31, and now marked by his bust,” a serendipitous concurrence given Loy’s interest in all things celestial (552).

Just as Loy’s paths crossed those of the Renaissance astronomer, his observational power stands as an authorizing presence in Barrett Browning’s own socio-historical, political, and personal observations of Italy. Imagine: Loy gazing upon the stars from the Villa dell’ Umbrillino, possibly thinking of Barrett Browning and Galileo walking these Florentine spaces before her.

Sixty some years after Barrett Browning’s poem, Loy moves to the Costa San Giorgio, just above the Casa Guido, and down the hill from Galileo’s house at #13 Costa San Giorgio.

This layered sense of place suggests how Loy “take[s] the vision” of Florence (to use Barrett Browning’s words) as a traversal of poetry, space, and time, creating imaginary circuits of vision for the poet and for the Florence wanderer reading her poetry.

Life on Costa San Giorgio

Having mused on these possible intersections, amble past the Casa Guido to enter the Costa San Giorgio through the narrow opening between wall and church, as Loy would have done many times. The Costa di San Giorgio, as home and studio, marks the beginning of her modernist path.

Loy’s expanding circle of avant-garde friends found their way to #54 Costa di San Giorgio (now renumbered as #60). In 1911, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas visited her home and studio while staying with Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia. Loy gifted Stein a small statue of a “Black Madonna,” and they shopped together in the Oltrarno.

In 1913, Gordon Craig moved next door for a period, and also that year, the American artist Frances Simpson Stevens arrived in Florence from America to rent a room from Loy after Haweis left Florence. The two women became close friends and together investigated the burgeoning Futurist scene, while also attracting Futurist artists to Costa di San Giorgio (Burke, Becoming Mina Loy). Loy also frequently wrote to her friend and literary agent Carl Van Vechten from her Costa home.

To reach Loy’s home, hike the street from its starting point in the Piazza San Felicita. The close confines of the cobbled street, lined by rows of three-storied houses with shutters on windows flung open or closed tight, resonate with Loy’s depictions of the street in the 1910s. Loy’s life on Costa di San Giorgio provided material for her earliest poems, most explicitly the two poems that form part of the triptych sequence of “Three Italian Pictures”: “Costa San Giorgio” (sic) and “Costa Magic” (see Firenze is a woman). Other poems evoke the street, either as a specific street or a more generic sense of street life.

Loy’s children ran across these street stones. The neighborhood’s characteristic closeness of homes, bringing neighbors into regular contact with each other, colors Loy’s experience of maternity. Widely considered the first poem about the physicality of childbirth, “Parturition” (1914 Trend) places its “I” in a domestic space on a busy street that also becomes the “centre / Of a circle of pain” in which the “I” grows cosmic in force and self-creation — but also remains within the house and its feminized environs (LLB96 4).

Shutters flung open, then as now, allow the outside world into the poem. Through the “open window,” the male “voice” of a “fashionable portrait-painter” is heard as he runs “up-stairs to a woman’s apartment,” a not so oblique reference to the kinds of infidelities she suffered with Haweis (LLB96 5). Loy’s son Giles was born on February 1, 1909, and a customary home-birth would have placed the event in the initial apartment on Costa di San Giorgio.

Whether this particular place housed the birth, where other women would have attended, the poem’s final lines indicate the woman-centered rituals of birth on this street, in a domesticized space that men do not enter. The visits of “Each woman-of-the-people” who are “Doing hushed service” and satirized as donning a “ludicrous little halo” are nonetheless present at the emergence of the speaker’s absorption into “infinite Maternity” of “cosmic reproductivity” (LLB96 7).

The doors on Costa di San Giorgio are varied and beautiful. In Loy’s poems, they come to signify gendered perspectives, passages, and the tension between mobility and enclosure. Women gather in “At the Door of the House” clustered around a Tarot card reader, “Looking for the little love-tale / That never came true / At the door of the house,” as the poem deromantizes myths of love (LLB96 35).

“The Effectual Marriage” begins at a door: “The door was an absurd thing / Yet it was passable,” and “Gina and Miovanni” “quotidienly pass through it”:

In the evening they looked out of their two windows

Miovanni out of his library window

Gina from the kitchen window (LLB96 36)

Peer up at windows flanked by shutters. In the heat of Florence’s summer, residents seek coolness in the evening air, spilling from houses into the street, viewed by the watcher at the window in Loy’s 1921 “Summer Night in a Florentine Slum,” in which a British woman gazes out at the activities of the street below her. Conscious of a privileged position of class and nationality, the speaker comes to question that position as she intuits her own complicity in the gender and class inequities she critically observes out the window (see Firenze is a woman).

From the Costa San Giorgio, let us now stroll in the Public Garden, the setting for “The Black Virginity” and its cast of priests, old men, and young girls out for a walk. Probably Loy sets her poem in the Boboli Gardens close to her home and identified by the Baedeker as a favorite site for Sunday strolls:

The Boboli Garden, at the back of the [Pitti] palace, extends in terraces up the hill. It . . . commands a succession of charming views of Florence with its places and churches. . . . The long walks, bordered with evergreens, and the terraces, adorned with vases and statues, attract crowds of pleasure-seekers on Sundays. (Baedeker 546)

In “Black Virginity,” a commentary on sexuality, religion, and masculine power, an “I in lilac print” observes the crowd. The strollers include a parade of priests, seeming novitiates who emerge from their “hermetically-sealed dormitories” cloaked with “fluted black silk” and a decidedly asexual authority. In their chastity, they dream “Not of me or you Sister Sarminata,” surmises the speaker, who sardonically notes this male authority’s dependence — since Eve — upon viewing woman as the origin of sin: “It is an old religion that puts us in our places,” for woman is made to be “Preposterously no less than the world flesh and devil.” The “Baby Priests” walk with others in the “Yew-closed” “green sward” of the park, alongside an “old man,” busy “Eyeing a white muslin girl’s school.” Through its placement of characters, the poem draws “parallel” lines between this suggestion of pedophiliac lechery and the Church’s denigration of women, reversing the notion of woman as the origin of sin and indicting patriarchal systems (LLB96 42-43). Staging this scene in a Public Garden counterpoints the Biblical myth of the Garden of Eden as the site of Eve’s transgression, suggesting its false justification for the “public” and private forms of masculine power enacted through and upon women’s bodies.

A Brief Jaunt on the Via dei Bardi

Turning eastward from the Ponte Vecchio on the Oltrarno side, the Via dei Bardi runs parallel to the river and just above its walls. The Baedeker from this period guides tourists to the home of George Eliot’s ‘Romala’,” another Florence connection to British literati, by taking the Via dei Bardi, “which leads to the left just beyond the Ponte Vecchio” (538). Loy marks her literary location on the Arno in several poems, including “Songs to Joannes.” Her apartment windows, perched above the river’s walled banks, open to a view of the Arno.

Walking along the Via dei Bardi, with the Ponte Vecchio at her back, Loy would enjoy a view of the river and the mountains rising in a distance outside the city.

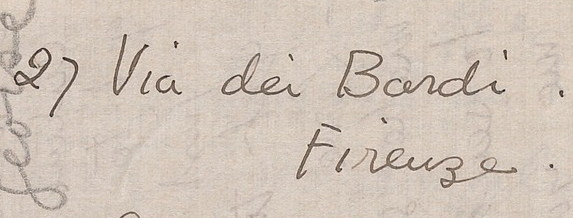

Loy settled temporarily on the Via dei Bardi when returning from several months in the mountain retreat of Vallombrosa just after the war began in the fall of 1914. Before leaving for the mountains in June, she had rented the Costa di San Giorgio home to tenants. Coming back to the city without her children — who were left in the care of their nursemaid in the mountains as the war intensified — she found an apartment at #27 Via dei Bardi.

Giovanni Papini lived just down the street. The Futurist rival of F.T. Marinetti, he became an intimate and short-lived obsession of Loy’s in a relationship frustrated, Burke reports, by his resistance. The summer after her residence on the Via dei Bardi, Loy’s “The Effectual Marriage” parodies this relationship and its gendered hierarchies in the figures of Mina, in her “kitchen window,” and Giovanni, in his “library window” (LLB96 36). Papini would again appear as Bapini, a rather ludicrously inflated ego, in “Giovanni Franchi.”

More mournfully, “Songs to Joannes” places the demise of love and relationship near the Arno. The male protagonist addressed in this long collage poem, most critics agree, is a amalgamation of Loy’s romantic entanglements, combining Marinetti and Papini and haunted by other love experiences. To this figure, the poem’s frustrated female speaker postulates, “We might have lived together / In the lights of the Arno” (LLB96 59), where her memories of their awakening intermingle the image of dawn over the river with eroticized language transforming the sexual act into a mechanical image:

Licking the Arno

Tongue of Dawn

Interferes with our eyelashes__ __ __ __ __ __ __ __

We twiddle to it

Round and round

Faster

And turn into machines (LLB96 63)

For a more sanctioned view of womanhood in this city of churches, the Baedeker directs us to wander down the street, beyond #27, where the street’s main historical interest can be found. There “rises the small church of Santa Lucia Magnoli,” known for “containing a relief by the Della Robbia above the door, and an Annunciation by Jac. del Sallaio (1st altar on the left)” (548).

The wide reproduction of Della Robia images sustained the profitable marketing of religious iconography in the city. Loy’s response to the commodification of such idealizing processes surfaces in Burke’s observation that, “marveling at the number of certified ‘Della Robbia’ Madonnas being shipped to America, she studied the pecking order among the dealers. Such persons conducted business by seeking to ‘fasten their right to exist upon the battered figurines of the Catholic past’” (Burke 124, quoting “The colonial lady artist,” a section among the fragments of Loy’s unpublished prose narrative Esau Penfold). Alert to the circulation of religious iconography as commerce, in an early poem “The Prototype,” Loy implicates religion’s role in enforcing poverty. Just as the poem denounces the idealization of the Virgin Mary as a way to distract attention from social and material realities, Loy maps the religio-economics of womanhood, virginity, and motherhood that pervade other poems in her Italian poetic Baedeker (see Firenze is a woman).

Returning to the Costa San Giorgio from Via dei Bardi, via Costa Scarpuccia

Loy left her flat on Via Dei Bardi and returned home to Costa di San Giorgio the spring of 1915. Walking from her rented apartment on the Via dei Bardi back to her Costa di San Giorgio home, Loy might well stroll past the Santa Lucia Magnoli and its Della Robia (traveling eastward on Via dei Bardi), turning right shortly thereafter onto Costa Scarpuccia. She would pass a small shrine to Saint Francis of Assisi on the right and one to the Virgin Mary just before this turn.

Should you want to trace Loy’s imaginary path, follow the Costa Scarpuccia up the hills, appreciating the shady trees lining the street.

Stop midway to catch a splendid view of the Duomo to your right. In a Christmas Eve setting at the Duomo, Loy counterpointed the Duomo’s Madonna with a poor and hungry mother in “The Prototype,” imagining the “birth” of a new social equality rather than the worship of an idealized Virgin and child (see Firenze is a woman).

At the top of the hill, cross over the Costa di San Giorgio to descend its lower part, walking toward the city (it will appear as the left street of a fork; the sharp left climbs upward on Costa di San Giorgio) You will be facing a corner building with a bas relief of the Madonna and Child above its door.

During the Spring of 1915, after several months living at 27 Via dei Bardi, Loy moved back to Costa San Giorgio, staying initially at #52 next door to her still-rented home. Both #52 and #54 sit across the stone street from the Chiesa San Giorgio, a medieval church that once housed Giotto’s Madonna di San Giorgio alla Costa (1295-1300) (removed at some point and attributed definitively to Giotto only in 1939).

Loy left Florence in October, 1916 to sail alone to New York City, where Francis Simpson Stevens helped her find an apartment and introduced her to the avant-garde circles important to her time there — beginning with the Arensbergs, the Provincetown Players, and Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, and expanding quickly to the Others crowd, imported Dada and Greenwich Village feminism.

Loy’s engagement with the avant-garde began on the Costa San Giorgio, in #54 (now #60) and evolved into a feminist en dehors garde in her writing from the Florence years. Visiting her Firenze homes brings to life the stones, windows, doors, and buildings she mapped in her emerging feminist poetics.

As a wonderful continuance of this artistic spirit, a house just uphill on the Costa San Giorgio now houses a ceramic artist, Emma Draghi, whose family has owned the home for two generations, since the 1920s. The wide doors of the bottom floor open to the studio and shop, well worth a visit to see her pottery and fabric creations.

Loy, Haweis, and Frances Simpson Stevens set up studios at various times on the Costa San Giorgio, where Emma Draghi now makes and sells her ceramics, fabric art, and knitted wears. The spirit of design and creativity across arts imbues her first-floor studios. Take a trip. Who knows what traces of Loy abound?