Loy’s Madonnas and “The Prototype”

Reading Mina Loy’s Florence poems and traveling through her adopted city, we move among the Carabinieri (militaristic police), the Ponte Vecchio, the Pitti Palace, the Duomo, the green shutters, the stony streets, the maternity hospital, Paschkowski’s Café, the trattoria, the Public Garden (probably the Boboli). We are joined by vendors, priests, nuns, Tarot card readers, nurses, artists and poets, fathers, and children. And there are many women.

Among the women portrayed on the streets and in the homes of Florence, images of mothers appear often. Laura Scuiriatti situates Loy’s maternal imagery in relation to Italian feminists of the period, who expressed interest in maternity and “the idea of a female body which becomes creative through a sexuality which may lead to maternity without hindrance.” They associated maternity with a form of political activism, ranging from arguments for a eugenics approach to recognizing a woman’s freedom to have children outside of marriage and to eliminate false oppositions of sexuality and motherhood (310).

Loy’s poetic images of mothers, whether on the street swarmed by children or in homes giving birth or downtrodden by poverty, insist on maternity as bodily and often oppressed. Satirically noting the Futurist disdain for woman collapsed with an envy for her reproductive capacity, “Lions Jaws” mocks “a manifesto / notifying women’s wombs / of Man’s immediate agamogenesis” (or asexual reproduction that ironically does not require a male) (LLB96 47). At the same time, the earlier “Parturition” links the birthing body and womb with an “infinite Maternity,” positing the maternal as a powerful site of “cosmic” intersections (LLB96 7).

An “infinite Maternity,” absorbing the mother into “The was ––is––ever––shall––be” reimagines a connection to divine maternity haunted by but resistant to the most heralded image of maternity in Catholic Italy, the Madonna.

Loy’s sly mention of the Madonna in “The Effectual Marriage” blurs an image of Mary typical to homes and streets in Florence with Gina, kept in her place (the kitchen) and denied her body:

Some say that happy women are immaterial (LLB96 36)

The Virgin body offers protection to others in its immateriality. The familiar iconography of the Virgin Mary protecting the faithful in the folds of her cloak or skirt finds its way into Loy’s poem, seeming to perhaps mock the image of the Madonna as complicit in enforcing womanly meekness, a trait that Gina has learned, “being female” (36). At the same time, the stanza devoted to the Madonna in this lengthy poem about gender power imbalances suggests that the immaterial, disembodied Virgin Mary is not divinely ordained but a construct produced by the cowardice of men, who hide behind (and depend upon) this disempowered version of womanhood:

Sundays a warm light in the parlor

From the gritty road on the white wall

anybody could see it

Shimmered a composite effigy

Madonna crinolined a man

hidden beneath her hoop

Ho for the blue and red of her

The silent eyelids of her

The shiny smile of her (LLB96 37)

Whether the viewpoint is looking from the parlor to an image of the Madonna on a roadside wall, or from the road looking into the parlor window, the view of the “composite effigy” includes a man hiding, the blank spaces of the lines punctuating his retreat behind the crinoline and beneath the hoop. The sexual innuendo playfully suggests an erotic stimulation and a not-so-virginal Madonna. Indeed, this female “effigy” signals a sly knowledge and even, perhaps, an erotic power, in the “silent eyelids” and the “shiny smile” – a patriarchal construct or “composite” of the blue robed Madonna as obedient and spiritually blissful who, nonetheless, conveys a secret that exceeds her image. Much like Gina, or the “mad woman” who “inspired” this “narrative,” the Madonna’s secrets (her pleasure, her voice) threaten the male-dominated worlds of religion and society.

Walking the city streets, now as then, one encounters Madonna icons, bas reliefs, statues, paintings, house decorations, and shrines. On the streets of Loy’s poetry, the Madonna, even if not explicitly named, associatively emerges in scenes of maternal women and their broods of children; the graphic process of childbirth; the maternity hospital; the marketing of women by their fathers; the abuse of women by their husbands; the poverty of women who must feed their children.

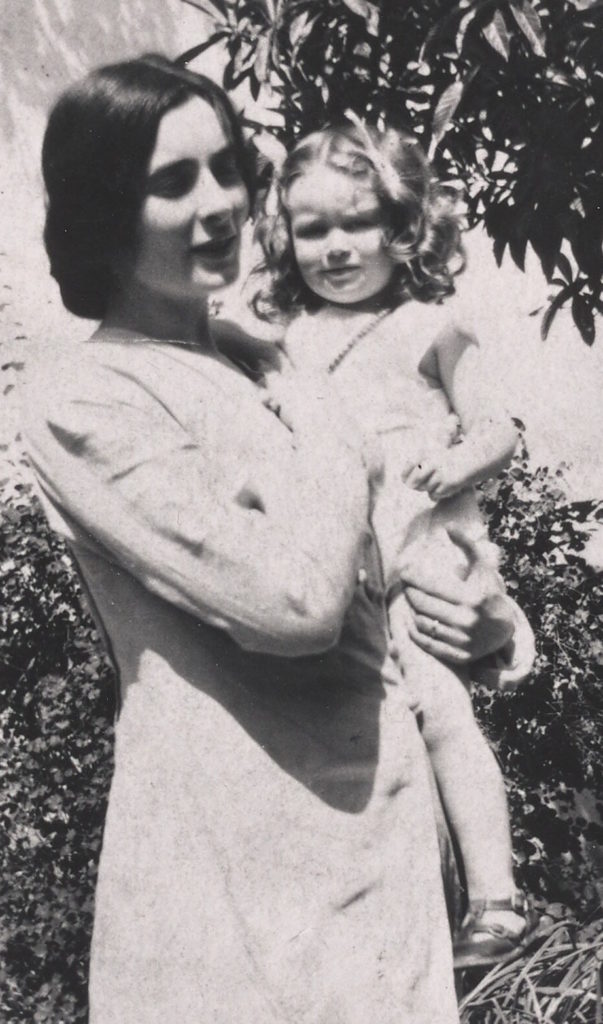

Associations between Loy and the madonna figure appear in friends’ memoirs. Gertrude Stein recalled a gift of a Black Madonna statuette from Loy’s studio, after a visit there. Loy was herself referred to as a Beautiful Madonna and associated with the maternal sacrifice of Mary. Mabel Dodge, calling Loy “Ducie Haweis” (Stephen’s nickname for her), judged her “lovely as a Byzantine Madonna” (European Experiences 338). The Madonna image shades Dodge’s mention of the loss of Loy’s first child, Oda Janet Haweis, born in Paris in May 1904 and dying of meningitis two days after turning one (Burke 98). Dodge describes a painting done by Loy on the night her child died, entitled “The Wooden Madonna” and bitterly satirizing the holy Madonna as a “foolish-looking mother holding her baby,” oblivious to the maternal suffering around her:

Stephen and Ducie met in an art school and had a stormy time in the Quarter together where Ducie lost her first-born girl and nearly went crazy; and then they drifted to Florence. The night Ducie’s little daughter died, she sat up all night and made the extraordinary tempera painting called ‘The Wooden Madonna” that I still have: the foolish-looking mother holding her baby, whose two small fingers are raised in an impotent blessing [340] over the other anguished mother who, on her knees, curses them both with great, upraised, clenched fists, and her own baby sprawling dead with little arms and legs outstretched lifeless, like faded flower petals. (342)

The painting, now lost, suggests to Burke a “refusal to take comfort in orthodox piety,” composing a “tension . . . between the promised consolations of divine motherhood and the pain of her loss” (Becoming 98-99) and prefigures her early poem, “The Prototype,” in contrasting idealized, divine ideas of maternity with the grievous realities of earthly motherhood.

During Oda Janet’s short infancy, Loy had painted a watercolor entitled “The Mother” (also lost), suggesting an intriguing pairing with the later “The Wooden Madonna.” Even the titles speak to the living state of motherhood and an inanimate idealization of it, one being earthly, the other being divine but “wooden.” “The Mother,” chosen for the 1904 Salon d’Automne along with six other watercolors, signals Loy’s interest as a woman in representing maternity. As a pair of paintings on motherhood, they must have spoken across that sad year of Loy’s life as a new mother. Having likely seen “The Wooden Madonna” while visiting Florence and Dodge’s villa in 1914, Carl Van Vechten wrote, “Was it only Mina Loy who dared protest sufficiently to paint her motherhood, with the dead child at her feet, upbraiding Mary?” (“Nightingale and Peacock,” Rogue, May 1915; later reprinted in his autobiography of pre-WWI European experiences, Sacred and Profane Memories, 91).

The “upbraiding” of Mary as an idealized version of motherhood motivates one of Loy’s earliest poems, “The Prototype,” composed in 1914. Setting the poem “In the Duomo, on Xmas eve” at a midnight mass of “1,000 candles,” Loy presents two infant births: one is the Christ child worshipped, a “cold wax baby,” “Perfect in pink-&-whiteness” with a “tinsel star / that rises on his forehead.” The other is the “new-born Hungry One,”

a horrible little

baby – made of half warm flesh;

flesh that is covered by sores — carried

by a half-broken mother. (LLB96 221)

The speaker, called “a heretic,” is the “only follower in Christ’s foot-steps / among the crowd adoring a wax doll,” for she alone worships “the poor / sore baby – the child of sex ignorance and poverty” (LLB 221). Rather than praying to a “god,” she prays to “humanity’s social consciousness” for reproductive education and economic equity, calling for the adulation of Mary and Christ child to be translated from abstract worship to concrete help for the “half-broken mother,” the earthly madonna and her sick child. She invites a “New Gospel” to replace the idealized Virgin and child (“Throw out the wax baby”) with a church of social justice (“Use the churches as night-shelters,” she urges).

The poem’s placement in the Duomo suggests a space rich with Mary’s imagery, in stark contrast with the poverty of the “half-broken mother.” The 1906 Northern Italy Baedeker describes the images of Mary particularly prominent above the portals to Il Duomo: “

Above the first door on the S. side is a Madonna of the 14th century . . . ; in the lunette, the Madonna between two angels . . . . The admirable bas-relief of the Madonna with the girdle, over the [N.] door, is ascribed to Nanni di Banco (1414).” (479)

The octagonal “space beneath the dome” includes windows designed from Madonna images by artists such as “Donatello (Coronation of the Virgin) and Paolo Uccello (Adoration of the Magi)” (as would be expected in an Italian Cathedral) and “behind the high altar is “an unfinished group (Pietà) by Michael Angelo (late work)” (sic, Baedeker 480).

Standing in the Duomo, imagine Loy in its vast interior, gazing upon the high altar where Christological typology aligns the new-born Christ child and the corporeal suffering body from the cross. Such paired iconography customarily links the Madonna’s iconographic innocence with her broken grief, the lamenting and distraught Mary of the Florentine Pietà (removed in 1993 to the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) fulfilling the prophecy of the Adoration. Loy’s poem inhabits that iconic connection between birth and death to reclaim the maternal as a site of justice rather than abstract divinity. In “The Prototype,” the mother of the Florence streets experiences a child in pain and hunger, echoing the Mary holding her dead child rather than the idealized Virgin and the “perfect baby.” The realization of Mary’s grief as an aid to mothers displaces the idealized birth’s distance, a turn toward Mary-in-pain that later suffuses Loy’s World War II poem “Aid of the Madonna.”

In calling for a “New Gospel” to be preached, for the church to “do for that mother & child in the light, what / the priests have tried to do in the dark” (LLB 222), Loy’s poem suggests the influence of her friend George Herron, an American she came to know in Florence when both participated in Mabel Dodge’s expatriate salons at her Villa Curonia in the hills outside the city.

Promoting the ideas of the Social Gospel Movement, Herron advocated a Christianity of social justice that viewed poverty and suffering as the result of systemic forces rather than personal flaws (Burke 275). As Keith Tuma notes, “Loy’s Christ emerges [at this time] as a valued spokesperson for democratic and communal values, an optimistic voice . . . [that] begins to take on the shape of Herron’s utopian socialism” (147).

At the same time, in Loy’s poem, maternity emerges as a feminist notion of divinity-in-self, a rejection of the church and society’s concurrent idealization and denigration of women. The traditional Madonna image of virginal, disembodied motherhood finds resistance in the pronounced images of bodily, difficult maternity appearing in Loy’s Florence poems – as in “the hips of women [that] sway / Among the crawling children they produce” (“Italian Pictures” LLB96 10) or the speaker’s rejection of the self-sacrifice expected of mothers, critiquing in “Babies in Hospital” the “atrophied / Woman-smile of your [a child’s] mother” and proclaiming “I cannot be your mother” to the ill babies under her care (LLB96 24, 26).

“Parturition” and a Feminist en dehors-garde

Most strikingly, “Parturition” asserts Loy’s feminist revision of the Madonna, situating maternity in the body that is coerced by social structures of power yet able to access a power particular to women. Loy gave birth twice in Italy, moving in the hot summer months to the cooler mountain resort of Bagni di Lucca to deliver Joella (July 20, 1907), while having Giles in wintery Florence about eighteen months later (February 1, 1909). The poem speaks to the female experience of parturition, a taboo topic for polite poetry.

Loy’s choice of the word “parturition” speaks to her Italian setting, for the painting genre of the Madonna del parto (or “Madonna in parturition”), appearing first in medieval Tuscany, featured the pregnant Mary and was venerated by pregnant women praying for safe deliveries.

Loy’s poem speaks to this lineage and translates the iconic Madonna into an expansive cosmic maternal energy absorbed by the delivering body.

In the midst of labor and becoming the “centre / Of a circle of pain,” the poem’s “I” finds that “Pain is no stronger than the resisting force / Pain calls up in me / The struggle is equal” (LLB96 4). The physicality of birth is fully evident – the “distorted mountain of agony” of contractions, the “delirium of night-hours” and the “gurgling of a crucified wild beast” attending the “foam on the stretched muscles of a mouth” (LLB96 5). The pain fosters a “Negation of myself as unit,” an emptying of preconceived and sanitized notions of birth and maternity. Synecdoches taken from nature yoke processes of life and death, the “infinite Maternity” and “cosmic reproductivity” the woman is “absorbed / into” (LLB96 7). The memory of a “dead white feather moth/ Laying eggs” and the “Impression of a cat/ With blind kittens / Among her legs” play across her mind as her body experiences parturition:

A leap with nature

Into the essence

Of unpredicted Maternity

Against my thigh

Touch of infinitesimal motion

Scarcely perceptible

Undulation

Warmth moisture

Stir of incipient life

Precipitating into me

The contents of the universe (LLB96 6)

Like the Madonna of Michelangelo’s late-life Florentine Pietà, the maternal knowledge of the “undulation of living” collapses birth and death, so that in death one sees birth and in birth one sees death. For Loy, this knowledge is not divinely obtained but arises from her “sub-conscious” and from its encounters with the world:

Impression of small animal carcass

covered with blue-bottles

—-Epicurean—-

And through the insects

Waves that same undulation of living Death

Life

I am knowing

All about

Unfolding (LLB96 7)

Perhaps Loy’s most provocative statement on maternity appears in her 1914 “Feminist Manifesto,” which calls on women to “demolish” the “division of women into two classes,” the mistress and the mother (LLB96 154). Enlarged typography and blank spaces enliven the prose to assert her point. Stressing marriage as an arrangement of commerce, or one of the “trades,” she notes that women who do not succeed in “striking an advantageous bargain” are denied maternity. Against this conscription, she argues that “Every woman has a right to maternity,” followed by a eugenicist-tainted (but not unfamiliar to Italian and American feminisms influencing her thought) declaration that “Every woman of superior intelligence should realize her race-responsibility, in producing children in adequate proportion to the unfit or degenerate members of her sex” (LLB96 155). In such statements, as critics have observed, Loy’s early feminism includes blind spots regarding social hierarchies privileging her own position as a white British woman. Across her work, such hierarchies and blind spots are both contested and adopted, a tension ambivalently unresolved in regard to class, race, and ethnicity even as she evokes her own Jewish heritage, as Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Cristanne Miller, among others, have explored.

Historically contextualizing Loy’s manifesto in relation to Italian feminism, Laura Scuriatti argues that maternity “is seen as a right in the ‘Feminist Manifesto’, and as a contribution to the betterment of the race, whereas it is equated with creation in ‘Parturition’”(308). Across both works, Loy’s visual sense of the page (typographical play, visual spaces, unusual lineations) redirects Marinetti’s “words in freedom” and the favored Futurist form of the manifesto to orchestrate a feminist response to maternal images proffered by Church and avant-garde alike. Some twenty years later, the 1935 sculpture “Maternity” suggests her ongoing concern with this theme, reimagining the triangular composition of Madonna imagery through an image of an earthy and everyday woman.

“Firenze is Florence . . . is a woman”

In rejecting an idealized association of “Florence” with an image of a beautiful woman, Loy’s poem “Giovanni Franchi” asserts:

Firenze is Florence

Some think it is a woman with flowers in her hair

But NO it is a city with stones on the streets (LLB96 30)

The stones reappear in “Songs to Joannes,” as the speaker’s “pair of feet / Smack the flag-stones / That are something left over from your walking,” just as she trudges through the labor of a relationship’s complex demise in that long poem, challenging romanicized versions of love (LLB96 55). As attentive to women’s plight under patriarchal church, state, and family as to the dynamism of the street, the specific place of Florence – the stones her feet “smack” – grounds the meshing of aesthetic and socially engaged modernism Loy develops in these years and in this place.

“The Costa San Giorgio” and “Costa Magic”

Loy’s speaker in “Costa San Giorgio,” the mid-section of the triptych “Italian Pictures” (ca. summer 1914, published in The Trend Nov. 1914), positions its keen observations of this Florence street within the viewpoint of the outsider, absorbing the “messiness / Of the passionate Italian life-traffic / Throbbing the street” while acknowledging that “We English make a tepid blot” upon this scene (LLB96 10). She and Haweis owned and inhabited #54 Costa di San Giorgio, an English presence on a hilly street of Italian neighbors in homes pressed tightly together, which Haweis left in 1913 to travel.

The vitality and energy of the street presented in the poem, roiling with movement and sensory sensations, chimes with representations of movement typical of Futurist painting. Boccioni’s painting, “the Noise on the Street Penetrates the House,” for example, models the “dynamic sensation” valued by the Futurists, challenging “the limits of classical perspective by breaking the barrier between the woman’s domestic space and the scene she sees from the balcony” (Burke 153).

In Loy’s poem, quick narrative vignettes present the scene. These snippets alternate with rapid collocations of fragments, blank spaces, synesthetic evocations, and geometries of light:

Oranges half-rotten are sold at a reduction

Hoarsely advertised as broken heads

BROKEN HEADS and the barber

Has an imitation mirror

And Mary preserve our mistresses from seeing us as we see

ourselves

Shaving

ICE CREAM

Licking is larger than mouths

Boots than feet

Slip Slap and the string dragging

And the angle of the sun

Cuts the whole in half (LLB96 11)

Indeed, the poem’s commerce with Futurism catches its first editor’s notice. Upon publishing the poem in Trend, new editor and friend Carl Van Vechten introduced Loy as a poet “in sympathy with the Italian school of Futurists,” who “has interested herself in the Italian Futurists, led by F.T. Marinetti, and for whom she has renounced the brush and taken up the pen” (Nov 1914, p. ii, 101; quoted in Burke 177). As a poet, nonetheless, her poem’s “affinity with Futurist painting” in the page composition’s “irregular lines and spacing” suggests the “dynamism of the Costa’s ‘live-traffic’” and its bold signage advertising goods for sale (Burke, 177). In response, most likely, to Van Vechten’s claims of Loy’s Futurist affiliations, she signaled her ambivalent sense of being on the periphery – both within and without the Futurist movement: “I am so interested to find I am a sort of pseudo Futurist – but very good for advertising – couldn’t I become an absolutist or something as I evolve?” (undated letter from Loy to CVV).

Loy’s ambivalence toward Futurism’s particularly aggressive avant-gardism was not lost on Van Vechten, particularly in relation to gender. Recalling a conversation at this time, he records that “Ducie Haweis” “gave sanction” to the opinion that Marinetti “loves noise and he loves war because it is noisy,” and that she added “that the futurists also were violent against women” (Sacred 116). She satirizes this point in “Giovanni Franchi,” as a parodic version of Papini, “Giovanni Bapini,” preaches to his young Futurist disciple of his knowledge “Of women––––––––––––”: knowing what he knows – or doesn’t know, the lines elongated blank black line suggests – he “would kill a woman / Quite inconspicuously it is true” (LLB96 30).

“The Costa San Giorgio” turns to Futurist techniques to consider the complicity of their rhetorical aims with social, psychological, and physical violence against women: the women in the poem are trapped in the social roles placed upon them. The bodies of mothers are devoted to breeding, as their “hips sway / Among the crawling children they produce.” Unmarried women have “little to do” but wait for “matrimonial beds.” The female “consumptive” whose “chair is broken,” is immobilized while others walk past her (LLB96 11, 10). The church and masculine militarism blur, as “The church hits the barracks / Where / The greyness of marching men / Fall through the greyness of stone” (LLB96 10; see Mapping Florence: First Tour, Loy at Home).

Currencies between male power, violence, and Futurist techniques play out in deadly fashion in “Costa Magic,” the third poem in “Italian Pictures.” Rapid shifts from word to word, often without connectives, produce a geometric fracturing of line, stanza, and page.

Such spatial attention to the page resonates with Futurist canvases and understandings of poetry that Marinetti’s “Words in Freedom” express (see Close Reading, “Costa Magic”). Men prove particularly ominous amidst these fractures and dynamisms.

The female speaker of “Costa Magic” is initially set apart from the street in observing Costa di San Giorgio, as was the (ostensibly same) speaker in “The Costa San Giorgio.” Significantly, unlike the first two poems 0f “Italian Pictures” (the first being “July in Vallombrosa”), the female speaker chooses to join rather than merely observe the community of women that forms to care for a sick neighbor girl, Cesira. This female community rises in response to the patriarch who looms over the street scene in disapproval of his daughter’s plans to marry.

Loy’s en dehors speaker steps to the “outside” margins of women’s experience in this rendering of the street, just as the poem stylistically dances around Futurist technique.

“variegated Madonnas”: Loy’s return to Florence, 1920

This outside position structures another observation of the city streets found in “Summer Night in a Florentine Slum,” written several years later after Loy’s involvement with the New York avant-garde circles that heralded her work and introduced her to her second husband. Having left Florence in 1916 to live for a period in New York City before migrating to Mexico to marry Arthur Cravan, she would lose him to a disappearance at sea and give birth to their daughter Fabienne within a few months. After Fabienne’s birth in England, Loy returned to the Italian city in 1920 to rejoin her other two children, Joella and Giles, who had been cared for by their nursemaid Giulia in her long absence.

Re-entering Florence in 1920, Loy’s place in the “new” poetry of modernism’s emergence – a poet now regularly published in avant-garde little magazines, recognized by international circles of avant-garde writers, celebrated and scandalized as a “modern woman,” and particularly acquainted with Futurism and New York Dada – distinguishes this moment from her earlier residence there. Writing a prose-poem sequel to the 1914 “Italian Pictures,” Loy signals a profound acknowledgement of the woman artist as “outside,” revisiting the street view from her home on Costa San Giorgio.

In “Summer Night in a Florentine Slum” (1920), this “summer-strewn street” located near the shop-lined Ponte Vecchio is decidedly “inopulent,” hotly mixing “tired dust” with arguments and intrigues on the street. Looking out her window at the “Latin families,” the speaker wearily sees them “lay on the lousy stones” of the street, “In what they could manage of an earthy abandon” (LLB82 81). Interrupting this uncomfortable leisure, raucous conflicts between the sexes, threats of violence and predation, and images of deformity twist the “passionate messiness” of the earlier poem into something foreboding, lurking, uncontainable.

Among the noise and activity are “variegated Madonnas scooping the air for a last gasp of a mother’s love and hairpins.” The “Madonnas” the speaker observes include the “hair strewn fury” of a “woman at home with four children” who is “big again” and – with a “gesture” that is “purest operatic” – accusing her husband “of being unfaithful” (LLB82 81). This “maddened woman” waits for her husband in the street all day, and only at dusk has she “slunk away to the imminent maternity hospital” (LLB82 83). A second mother and her husband, “friends of mine” who live in poverty, come to the window:

Sophia came up to the window, with her husband, and a large wicker perambulator some

goddess had showered philanthropically upon her . . . so babies fell about in it, on the wooden bottom.Sophia was lovely and ran like a spider, curls and skirts behind her . . . very beautiful indeed. (LLB82 82, ellipses added)

The “variegated Madonnas” populating the streets in images of the Virgin Mary blur with images of actual mothers, a point of momentary connection for the speaker. At the end of the piece, however, she withdraws her gaze and any contact with the Italian street back into a specifically English space: drawing in her head from the window, she “pulled the English chintz curtains scattered with prevaricating rosebuds; and Beardsley’s Mademoiselle De Maupin drew on her gloves at me from the wall” (LLB82 83). The British image hanging on the wall (rather than a Madonna) seems somehow to accuse the speaker, signaling disapproval in a feminine gesture of pulling on her gloves while eyeing the speaker eyeing the street.

What do we make of this immersive view of the street, coupled with such strong gestures of separation from it?

Loy’s awareness of her own complicity in a British attitude of superiority (arguably informing “July in Vallombrosa” also) suggests a self-perception that alternates from Futurist haughtiness and Dada parody, rendering her en dehors viewpoint complexly aware of the hierarchies embedded in any act of framing, selection, and representation. The pulling of the curtains, coded as a specifically British-borne act of dismissal, communicates her refusal to exempt herself, as artist, from such social prejudices that shape her capacity to perceive and re-present. The prose piece morphs into a self-critique of her retreat to social privilege that betrays the mistreated and the marginal figures on the street by making them invisible, an invisibility that the speaker nonetheless shares behind the curtains.

Florence is a woman, is a stone, is hips swaying from childbirth, is women beaten, is a bug on a dead body. The en dehors garde enters in to this modern arena, stepping outwardly toward taboo topics of birth and sex, and stepping into the choreography of the Madonna/maternal only to change it.