Roma and the First Free Futurist International Exhibition

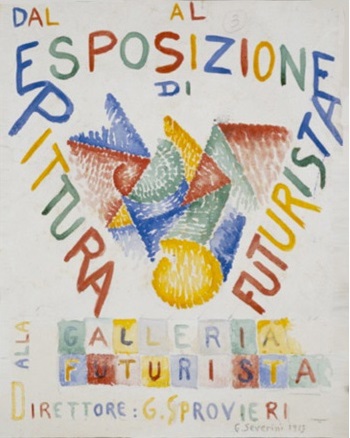

When in Rome, stroll down the Via dei Tritone, a busy car-filled street near the Piazza Barberini. Amidst a looming sequence of 19th-century buildings, number 125 sports lions’ heads above the formidably heavy doors that opened on December 6, 1913 to the Galleria Futurista di Giuseppe Sprovieiri (the dark door in the center).

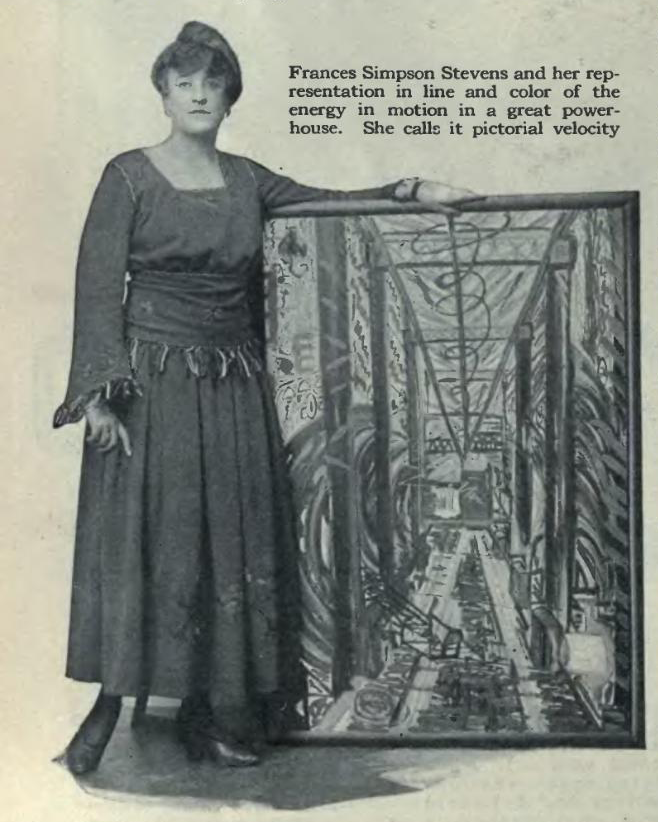

Shortly after its establishment, the Galleria Sprovieri held the First Free Futurist International Exhibition in February and March of 1914.  Loy contributed four paintings to the show, including three portraits of Marinetti and a painting entitled a “dynamism of the subconscious” (all now lost). Her friend Frances Simpson Stevens, the only American in the exhibit, showed eight paintings, including Dynamism of a Market, Dynamism of Pistons, and Typographic Simultaneity. Work by Marinetti and various Russian Futurists rounded out a show that Sprovieri hoped would shake the “provincialism of Italian art” (Burke 166).

Loy contributed four paintings to the show, including three portraits of Marinetti and a painting entitled a “dynamism of the subconscious” (all now lost). Her friend Frances Simpson Stevens, the only American in the exhibit, showed eight paintings, including Dynamism of a Market, Dynamism of Pistons, and Typographic Simultaneity. Work by Marinetti and various Russian Futurists rounded out a show that Sprovieri hoped would shake the “provincialism of Italian art” (Burke 166).

Loy met Marinetti at the Stazione Centrale Santa Maria Novella, the rail station near the church and piazza of the same name (the station was rebuilt in the 1930s just a slight distance from its original setting). They traveled to Rome to see the show and spend a few days together. Fearful that Stephen, then in New York, would discover her travel with another man, she nonetheless decide to “run the risk” of travel to Rome rather than “to stagnate in Florence” (Burke 165). Her account of the experience appears in the archival fragments of in a semi-autobiographical novel recounting her relationships with Marinetti and Papini, entitled Brontolivido. She described Marinetti’s energy in Futuristic terms, linked to the “rhythm of the railroad” (Burke 165). She confessed that “she was caught in the machinery of his urgent identification with motor-frenzy,” in a world where “everything seemed to be worked by a piston” (Burke 165, quoting Loy).

Such energy also characterized Marinetti’s impromptu performances at the gallery, which included manifesto-like speechifying and a planned mock funeral for the “old philosophies” killed off by Futurism (Burke 166-167). Prompted by conversation that had turned to Papini’s “latest diatribe in Lacerba, a bitter, almost hysterical call for the suppression of women,”

Marinetti seized upon the occasion to harangue the group on the difference between Futurist obscenity and Papini’s foray into the genre. Papini had reduced woman to her sexual organ, he bellowed: ‘a urinal of flesh that desire represents to itself as the chosen recipient.’ This ugly attack was a blow to Futurism, he went on; it would alienate the movement’s best propagandists, the women. ‘Woman,’ he roared, ‘is a wonderful animal, and when I put into print any part of her body I choose, it is in purest appreciation . . . . I do not admit that I can write about a fondant [a creamy confectioner’s base used in candy-making] which gives me some pleasure — & not about a vagina which gives me infinitely more. This is a beautiful word, it means what I say.’ (Burke 166, quoting Loy, Brontolivido)

Such boldness of language startled the crowd and “awed” Loy, eager for ways to break through the restraints placed upon her sex and the capacity to speak of female experience – but she would do so by resisting and critiquing the misogyny underlying Futurist proclamations about women and the female body (Burke 166).

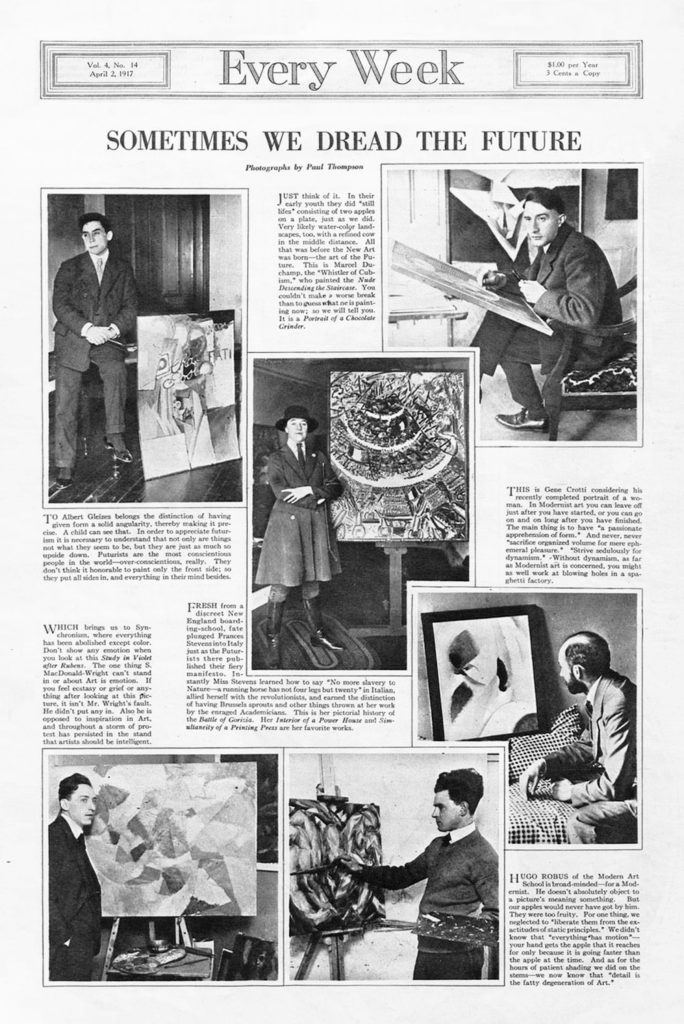

Stevens and Loy, noted at the time for their involvement with the Futurists, each dropped out of official histories of the the movement. Stevens’ subsequent involvement with avant-garde circles in New York shows up in such publications as Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work and, more popularly, a gallery of (otherwise) all-male artists collaged on the pages of Every Week (April 2, 1917). These glimmers of the en dehors garde – remaining on the outskirts, coming from the outside – show “Miss Stevens,” in the array of artists photographed with their work for Every Weekly, evocatively centered on the page and sporting male garb. She is assuming the avant-garde position, among and with men, while slyly subverting it in her cross-dressing stance.

While Every Week clings to typically sexist methods for framing Stevens’ accomplishments –presenting her as an innocent ingenue swept up by “fate” – the presence of Stevens in this photo-story evokes larger questions concerning how women artists negotiated a sexist inheritance persisting in even the most radical of avant-gardes. Certainly, this negotiation speaks to the en dehors garde positions that Loy, and Stevens, would take in art, poetry, and their lives.

The First Free Futurist International Exhibition in Rome coincided with such negotiations for Loy. Her emerging poetry challenged conventions of gender by experimenting with topics deemed improper for women, bringing women’s bodies and subjectivity into visibility through penning such works as “The Prototype,” “Parturition,” “Italian Pictures,” “Three Moments in Paris,” “Virgins Plus Curtains Minus Dots,” “Songs to Joannes,” and the unpublished “Feminist Manifesto.” Loy’s focus on an insistently embodied female sexuality in these works bespeaks a materiality shaped by economic, religious, and social systems disallowing women from defining their own erotic, maternal, and bodily experience and knowledge. Her writing presents women’s bodies within such systems and too often circumscribed by men’s voices, such as Marinetti’s bombastic appropriation of “vagina” to ostensibly argue his feminist bona-fides.

As widely recognized, Loy criticized the duplicity evident in Futurism’s rhetoric of “woman” as a figure of muse-like usefulness but weak, even disgusting, agency. Pushing back against the Futurist presumption that a man could either define or offer knowledge about women, Loy resisted this conquering, militant rhetoric of gender, stepping otherwise. Loy’s poems about women from the Futurist Florence period offer a rebuke to her male contemporaries, as she moved both within and without their concepts and spaces of radical art.

For Loy, radical art and action included speaking to taboo topics, as a woman to other women. Writing to Carl Van Vechten about “Parturition” in a letter of October 29, 1914, she declared, “I am glad to introduce my sex to the inner meaning of childbirth. The last illusion about my poor mis-created sex is gone” (quoted by Conover, LLB96, 176).

As recounted by Carolyn Burke’s biography and addressed by a wide range of critics, Loy’s Futurist encounters fundamentally shaped the experimental and feminist directions of her writing, as she both absorbed and resisted the movement’s ideas and techniques. Adopting forms from Futurist models, “Aphorisms on Futurism” (Camera Work, January 1914) and the “Feminist Manifesto” (1914) test out genres favored by the Futurists, unconventional elements of typography and spatial arrangement, and a language of dynamism, change, and shock. Poems like “Three Italian Pictures” or “Parturition” encourage sensations of rapid shifts, movement, and energy that Futurist painters developed through bright colors, fractured spaces, and geometric lines of force on their canvases. Loy’s plays from this period prod the movement’s sexism and attitudes toward audience (see Courting an Audience: Loy’s Plays), and the satires – “Sketch of a Man on a Platform,” “Giovanni Franchi,” “Café du Néant,” “The Effectual Marriage,” and “Lions Jaws” skewer Futurism’s masculine avant-gardism while freely adopting and reworking its techniques.

Florence as Futurist Canvas

The small Renaissance city of Florence, in the hands of the Futurists, transforms into a canvas and stage for performing Futurism and its assault on the art traditions that the city so aptly represents. Asserting that “Futurism could only have been born in Italy, a country absolutely fixed on the past,” the new movement heralded the call to “spit on the Altar of Art” through art and literature but also vigorous public debate and spectacle (Aldo Palazzeschi, in Burke 152). A wander through the city finds sites familiar to Loy’s encounters with artists and writers of the movement.

Our tour of Futurist Florence begins, appropriately, with Loy’s Costa di San Giorgio home. Loy rented Stephen Haweis’s studio, upon his departure from Florence in 1913, to the young American artist Frances Simpson Stevens, arranging with her mother to “chaperone” the twenty-year old. The women’s adjacent studios energized each other’s work and attracted the attention of Futurists. Having studied with Robert Henri and exhibited at the Armory Show, Stevens sought out Futurist painters Carlo Carrà and Ardengo Soffici, who, along with Giovanni Papini, “began turning up at the Costa San Giorgio in hope of enlisting her in the movement” (Burke 151). At the time, Gordon Craig, the theatrical designer hoping to start a modern school of theater, lived next door, making #54 Costa San Giorgio an active hub for new art ideas.

Wandering down their stony street to cross the Ponte Vecchio into the center of town, Loy and Stevens often headed toward the Piazza Viottorio Emmanuelle (now the Piazza Della Repubblica), where artists and writers gathered in cafés around the corner from the Duomo.

The women likely attended the Futurist painting exhibit in November, 1913 held at the Saletta Gonnelli, a covered courtyard at the Liberia Antiquaria Gonnelli, a bookshop frequented by Giovanni Papini and Gabriele D’Annunzio and located near the Duomo at Via Ricosoli, 6r (and still in business). This first showing of major Futurist artists in Florence received reviews in Lacerba, the Futurist little magazine.

Lacerba originated nearby, developing out of and reporting on Futurist debates and animated discussions often taking place at the Caffé Giubbe Rosse.

Lacerba was first established in this café by Giovanni Papini and Ardergo Soffici. Soffici’s articles about the Café Giubbe Rosse mention the conversations of Loy and Stevens (Lacerba Jan. 15, 1914, p. 30; in Burke 153). Still in operation (and serving fabulous coffee, pastries, and thick Florentine grilled steaks), the Café Giubbe Rosse’s high vaulted ceilings and dark wood trim transport the visitor back to the early twentieth-century. The art and photograph-covered walls and Futurist-themed menu covers celebrate its history as an incubator of modern art.

Directly across the same Piazza, Loy met with Futurists and others at the literary café Paszkowski’s, mentioned in her satirical poem “Giovanni Franchi” (Rogue 2.1, Oct. 1916; composed May-July 1915).

The poem parodies the homosocial circuits of adulation among Futurists, figuring a young aspirant (the fictional Franchi) whose worshipful relation with an older “philosopher,” Giovanni Bapini (aka Papini) verges on pederasty. Naively adolescent, with “sensitive down among his freckles,” and suspect to patriotic propaganda for Italy’s declaration of war, Giovanni Franchi’s Futurism is intertwined with the “patriotic souls of flags / Red white and green flags,” a nationalism “filliping piazzas” or stirring up Italian publics spaces. The “ ‘National Idea’ arrived on the Milan Express” — Marinetti’s descent upon Florence from Milan and his clamor for war — colors not only the red, white and green flags of the relatively new nation but superficially tinges the authoritative rhetoric of the Futurists Papini and Marinetti. A parodied air of self-importance infuses the spectacle staging of Futurism, such as Giovanni Bapini’s speeches issued through “monumental gums” that “importuned mobs.” Rushing in and out of gatherings, the younger Giovanni strives to imitate this posture, unaware of its ridiculous emptiness, as he rushed “from Paszkowki’s / Through plate-glass swingings / To look as busy bodily / As the philosopher’s brain” (LLB96 28). The Futurist philosopher and his heir, intent upon a window display of profundity, is merely a mental busy body.

Tracing the Futurist proclivity for spectacle, the Florence map might further take us to the Piazza San Marco, a five-minute walk from Paszowski’s and Café Giubbe Rosse away from the Arno river. In 1913, Marinetti climbed the bell tower to drop “800,000 copies of his speech against ‘passéist Venice” (Burke 152).

Furthering the performance of revolt and shock, Futurists took up the stage at the Teatro Verdi, on the Via Ghibellina, not far on foot from the bell tower. The corner building is fronted with arched door entrances and lovely iron scrollwork on the lamps and exterior brackets. Still a central performance site, the Teatro Verdi advertised a show for Elvis Costello when I strolled by in the spring of 2017.

On December 12, 1913, Loy attended the Futurist serata, a performance and “riot” in which the audience, provoked by the performers, threw rotten vegetables at the manifesto and poetry readers on stage to create a frantic explosion of Futurist energy (see Courting an Audience: Loy’s Plays).

Loy’s “Futurist” Maps of Class and Gender

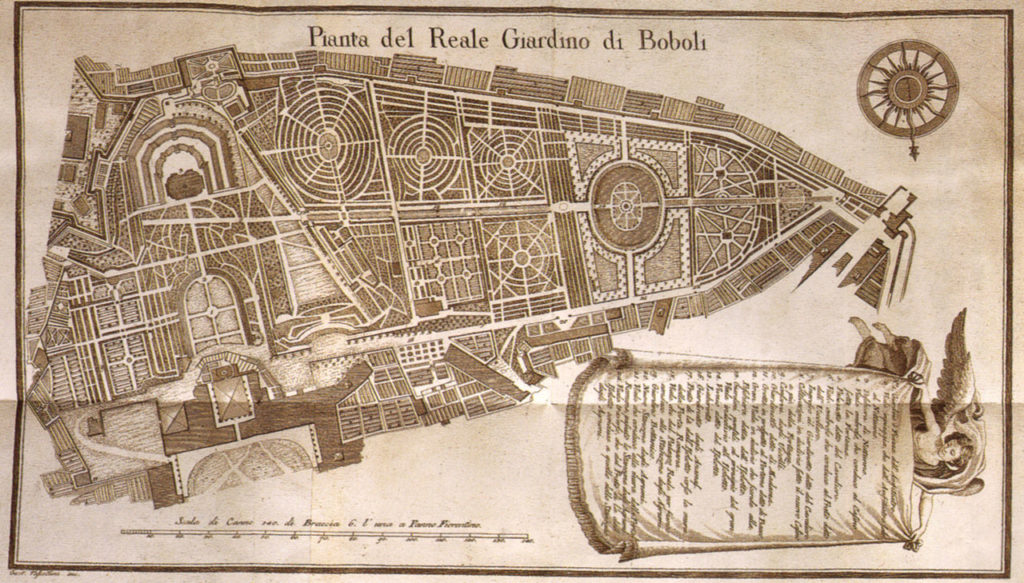

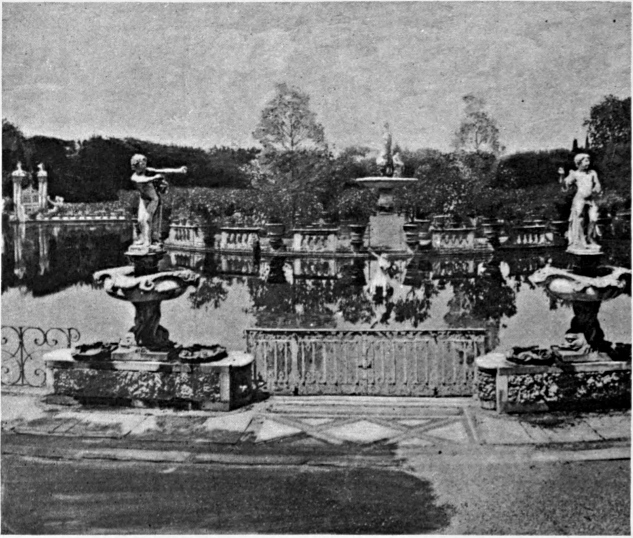

The Florence map drawn of Futurist spaces, crossing over Loy’s poems of this period, suggests that beneath the Futurist display of antics and spectacle, undercurrents of class and gender dilute the movement’s radicalism. Loy most explicitly tours Florence’s Futurist spaces in her poetic satire “Giovanni Franchi,” set in the shadows of the Pitti Palace. The Pitti Palace is located in the Oltrarno (across the river Arno) at the foot of steep hills laced by streets like Loy’s Costa di San Giorgio, which empties into a piazza a block or so from the Palazzo. From her home on the hill, Loy could also stroll through the public Boboli Gardens to access the Pitti Palace from the rear. These expansive gardens spread down the hillside behind the Pitti Palace and its rather solemn grandeur, offering a respite from city crowdedness and an opportunity to amble on any number of paths past fountains and statues amidst the foliage. Loy sets “Black Virginity” most likely in these gardens (See Mapping Florence: Second Tour, Friends).

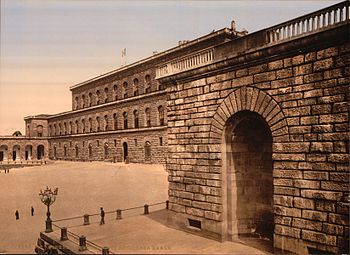

Loy shopped and frequented eateries in the Oltrarno (shopping with Stein and Toklas there), choosing this location to chart the city’s and Futurism’s social architecture in “Giovanni Franchi.” The poem cuttingly counterpoints the class position of its young protagonist, “hooligan-faced and latin-born,” with the aristocratic pose of the Futurist leader, ironically made to chime with monuments glorifying an aristocratic past ostensibly scorned in Futurist rhetoric. The haughty “Bapini” (a mocking play on Giovanni Papini), claiming that “Everybody in Firenze knows me,” shares physical attributes with the “stolid” Pitti Palace, the 15th-century palatial home housing the Medici family in the 16th century, followed by ruling families in Tuscany and, in the 18th century, used by Napolean (LLB96 28, 29).

In the poem, the young “disciple” sits across from the grand Pitti Palace–the Palazz0– in the / “Audaciously squatting” trattoria (eatery) kept by his working-class “papa and mama,” “watching the munchers supporting his parents” (LLB96 29). The “imposing palace” first built by a private citizen would become the “residence of the reigning sovereign” by 1550, continuing to be “that of the King of Italy when at Florence,” the 1906 Baedeker informs its readers (538). As with the aristocratic posture adopted by Bapini, the Palazzo’s “stolid” grandeur dwarfing the small shops and eateries across the street, architecturally disregards its proximity to the work-a-day establishment. Loy imagines the world existing beneath the Palace’s gaze rendered invisible to the higher echelons claiming to be all-seeing but nonetheless willfully blind:

The Pitti Palace however stolid could hardly help noticing

Being an aristocrat it went on looking. . .

The Pitti Palace has never been known to mention the trattoria

Or mention Giovanni Franchi

Sitting in it (LLB96 29)

Despite aristocratic efforts of the anthropomorphized palace to remain aloof, collisions and intersections of class and gender are all too evident on this street fronting the Pitti Palace. Loy focuses on the discrepancy between the palace’s history of grandeur and the working establishments and people around it.

A slippage between the female references in the poem seems strategically linked to the street’s architecture. The poem’s early stanzas introduce a figure of “threewomen” — a seeming composite of women or parts of a single woman. In a mindless devotion to the Futurist leader shared by the women and Franchi, the “threewomen” “Skipped parallel / To the progress / of Giovanni Franchi.” References to the “threewomen” morph into pronouns connoting different kinds of consciousness, becoming a singular “she” by mid-poem, ostensibly “to save time” (a “she” is shorter to read or say than the multi-syllabic “threewomen”); at other points, an “I” speaks, suggestive of Loy (LLB96 27, 29). The “she” visits the trattoria, where even the food suggests a kind of brainwashing she (and Franchi) have fallen prey to: the trout “might have been trained for circuses” and the mayonnaise “helped her to forget / That what is underneath need never matter” (LLB96 31). Loy’s blank spaces suggest something is always silenced and “underneath” in structures of power lived out by Bapini and the souls of masculine aristocracy marking the Florentine avant-garde. What is “underneath” also suggests the mark of woman’s difference underneath her clothing that indeed matters, but is silenced (made a blank space) by masculine authority. Recalling Marinetti’s bold claim to the word “vagina” at the Rome Sprovieri exhibit, Loy here suggests that the Futurists had little actual regard for female genitalia or sexuality.

The male to male transmission of knowledge sustains this soul, particularly in shaping attitudes toward women. As the younger Giovanni “listened at the elder’s lips,” he learned of “earthquakes and women”:

Of women———————–

His manners were abominable

He would kill a woman

Quite inconspicuously it is true

And neglect to attend her funeral

I mean the older man

And what he told

Giovanni Franchi

About those pernicious persons

Was so extremely good for him

It entirely spoilt his first love-affair

To such an extent it never came off (LLB96 30)

Adopting the first person pronoun (“I” and then “we”), the poem slides between a speaker who is the “I” but also the “she” composite of the “threewomen,” oscillating between keen critique of the Futurists but also her own willful obliviousness concerning the gender politics of this arrangement. The “she” is indicted for following (or perhaps just ignoring) the cultural gender script, while the “I” recognizes the cultural texts at play, including Bapini’s bitter misogyny (and a vicious commentary on her intimate but failed relationship with Papini). As in other poems, Loy’s en dehors strategy implicates herself in the politics she critiques, recognizing and critiquing her simultaneous positions — as “threewomen,” as “she,” and as “I” — both outside of and entangled in the Futurist dynamics the poem parodies.

Loy’s positioning of the “I” in the poem connects with the outside status so often taken up in other of her Florence poems, by virtue of her gender and her foreignness, and that critically inscribes an en dehors garde approach into her feminist poetics – a stepping toward the outside. One might read this positioning in her sly reference to the foreigner’s travel guide, the Baedeker, when she writes (in first person):

We have read of

Trattoria meaning eating-house

Piazzas or squares

The Pitti Palace enormous

And Paszkowski’s for beer

All are in Firenze

Firenze is Florence

Some think it is a woman with flowers in her hair

But NO it is a city with stones on the streets (LLB96 30)

The 1906 Baedeker’s entry on the Palazzo Pitti (538-541) makes not only as an architectural statement about power and wealth but also as a treasured gallery of art: “No gallery in Italy can boast of such an array of masterpieces” (539), which the Baedeker catalogues over the course of three pages. Indeed, the poetic irony of Bapini’s correspondence with the Pitti Palace mocks the Futurist disdain for the traditions and Art of the museum as a pronounced hypocrisy. The city is not the romanticized woman with flowers, but a hard and stoney place.

Tara Prescott usefully cites the “echoes” from the “Baedeker guide’s entry for this city found in the “language of these lines” in “Giovanni Franchi,” finding that the “Baedeker guide’s entry for this city” helps to establish connections between the popular travel guides –which would define “trattoria” and “piazza” for British inhabitants like Loy – with Loy’s work (21).

En dehors Baedeker

As a book instructing foreigners how to interpret unfamiliar places and words, the Baedeker frames experience for the traveler. Analogously, the culturally framing texts of masculine misogyny, depicted so bitingly in the preceding stanza’s discourse on women issuing from the “elder’s lips,” depends upon an idealized interpretation of woman (like Florence, or the goddess Flora, with flowers in her hair). This pernicious idealization, Loy recognizes, is like the trattoria’s “mayonnaise,” covering over what is underneath. The flowers conceal the hard stones trod by Futurism’s royalty, just as their words of praise – remember Marinetti’s ode to the vagina and insistence that “woman is a wonderful animal” – insure a woman’s place is “underneath.” Loy’s feminist Baedeker challenges this Florentine / Futurist map, drawing up one of her own making.