Welcome to Mina Loy’s Italy, a poetic geography inspired by her work and life in Florence from 1907 until 1916. Walk the stony streets to track her residences, homes of friends, gathering spots, galleries, landmarks, vacations, and views suggestive of her Italian poems and life. Loy’s turn to writing coincides with her years of living and traveling in Italy. Her poems from this near-decade offer a Baedeker guide for her readers seeking to retrace her early en dehors garde steps as a poet—one who turns outward from norms and conventions.

Welcome to Mina Loy’s Italy, a poetic geography inspired by her work and life in Florence from 1907 until 1916. Walk the stony streets to track her residences, homes of friends, gathering spots, galleries, landmarks, vacations, and views suggestive of her Italian poems and life. Loy’s turn to writing coincides with her years of living and traveling in Italy. Her poems from this near-decade offer a Baedeker guide for her readers seeking to retrace her early en dehors garde steps as a poet—one who turns outward from norms and conventions.

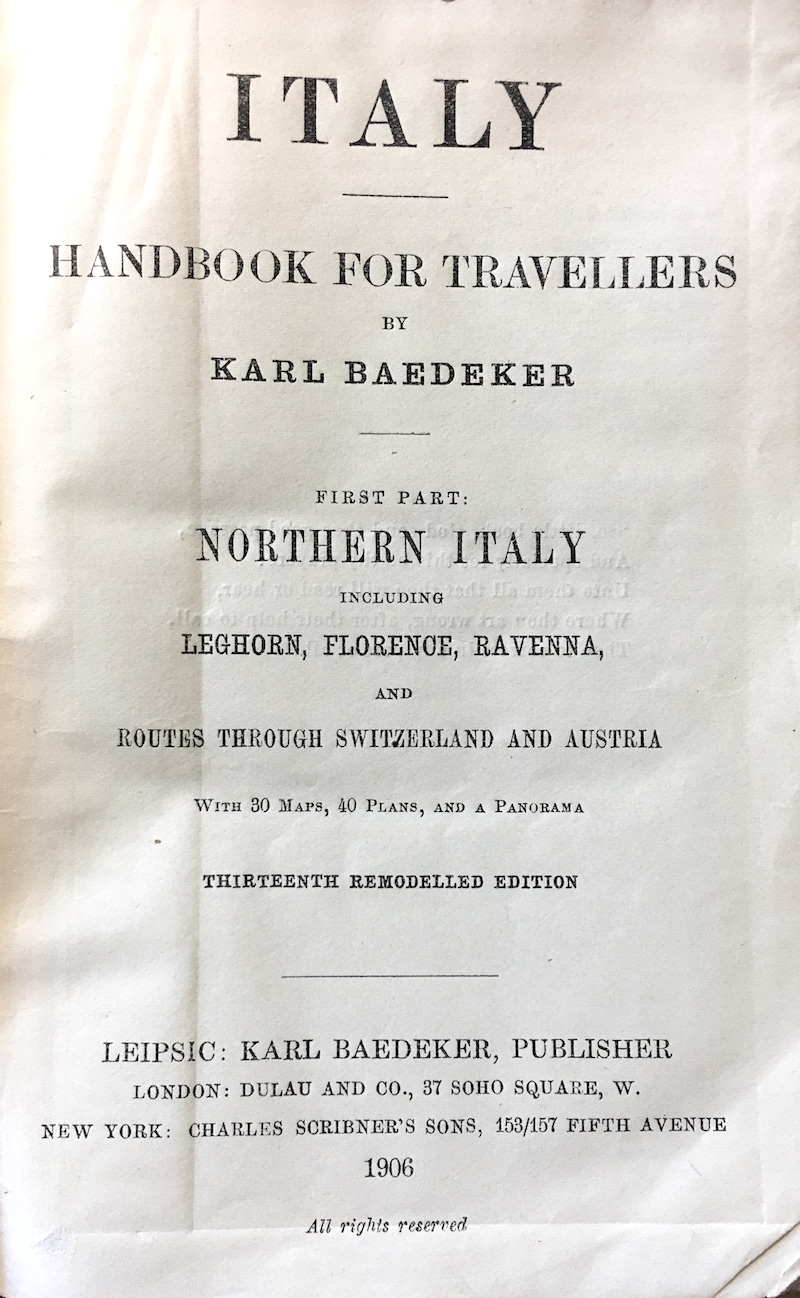

Indeed, maps and guides inhere in Loy’s language, art, and design creations. Carolyn Burke invites us to understand Loy as a “cartographer of the imagination” who deploys “metaphors of self-discovery.” These metaphors use “maps and Baedekers” to “symbolize the quest that shaped her transits through the modernist landscape” and her exploration of self (vi-vii).

Imagine what Loy’s own Italian Baedeker might include and where it might take us. Imagine a layering of geographic, social, and poetic spaces, routes that trace the artist’s steps into writing, feminism, avant-gardism—imagined steps we might follow through the Italian transits and traversals attending Loy’s emerging en dehors garde cartographies—moving toward and from the margins, aware of the center but stepping differently. How does mapping Loy’s Florence and Italy help us understand those transits?

Streets, gardens, eateries, palaces, and churches populate the poems of Loy’s Italian Baedeker. These byways, pathways, and spectacles conjoin in an “imaginary cartography” with social and gendered geographies. Most notoriously, Loy’s satires of Italian Futurism, such as “Giovanni Franchi” and “Lions’ Jaws,” conduct guided tours of Florence’s avant-garde via thinly disguised pseudonyms—“Bapini” for Giovanni Papini or Imna Oly for herself—upon the places populating the poems. “Giovanni Franchi” shifts, for example, from the geography of nobility —such as “The Pitti Palace enormous”—to“Paszkowski’s for beer,” a place of the people (and the Futurists) in the Piazza Vittoria Emanuele (later the Piazza della Repubblica) (LLB96 30). As Laura Scuriatti remarks, “Florence was a space of complex cultural exchanges, where ideas about cosmopolitanism, national identity and culture were discussed, and transnational projects implemented in parallel with specific versions of modernist and avant-garde experimentation” (303). Loy’s poetry illuminates a constellation of figures, histories, and places that inform Florence’s avant-garde energies.

For Loy, navigating the Italian city was as much a matter of language as of physical orientation. In “Giovanni Franchi,” the poem’s speaker enacts linguistic translations necessitated by place, suggesting the usefulness of an English-language tour guide like the Baedeker for the English speaker in Italy (see Prescott 20):

We have read of

Trattoria meaning eating-house

Piazzas or squares (LLB96 30)

Loy’s navigations of poetic language, as she moved between painting and writing during her Florence years, suggest how the concurrence of language shifts (from English to Italian) and geographic shifts (from England and France to Italy) provide critical context for her shifts in media, from canvas to page, from visual modalities to verbal. Not only shifts, but oscillations or cross-currents between the poles of these shifts attends Loy’s movements in a new city, among new places and acquaintances.

Touring with the en dehors garde

Each street of Florence contains a world of art; the walls of the city are the calyx containing the fairest flowers of the human mind; — and this is but the richest gem in the diadem with which the Italian people have adorned the earth.

Baedeker’s Northern Italy 30

Florence (170 ft.), Italian Firenze, formerly Fiorenza, from the Latin Florentia, justly entitled ‘la bella’, is situated in 43° 46’ N. latitude, and 11°21’E longitude, on both banks of the Arno, an insignificant river except in rainy weather, in a charming valley of moderate width, picturesquely enclosed by the foothills of the Apennines on the N. and by the spurs of the Monti di Chianti . . . on the S[outh].

Baedeker’s Northern Italy 30-31

Firenze is Florence

Some think it is a woman with flowers in her hair

But NO it is a city with stones on the streetMina Loy, “Giovanni Franchi” (LLB96 30)

Touring Florence and Italy through Mina Loy’s poems, this chapter guides the traveler through places that Loy and her poetry inhabit in the cluster of poems she wrote while living in Florence between 1907 through 1916, or in the years shortly thereafter that reference Italy. These poems comprise a poetic, imaginative, imaginary Italian Baedeker.

As such, Loy’s poetry offers an alternative choreography of place to both literary and popular accounts of Italy. At times, poems haunted by the grand tour, epic, or picturesque narratives proliferating among nineteenth-century British writers (think Byron, Shelley, Barrett Browning) retrace and revise Italian place, employing a feminist and modern compass.

This compass also directs Loy’s approach to the popular guidebooks developed commercially for English-speaking tourists, the Baedeker tour guides, which supply the title for a poem and two books of poetry (“Lunar Baedeker,” Lunar Baedecker 1923 [sic], and Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables 1958). In the prefatory quotes above, the first two from Karl Baedeker’s 1906 Italy Handbook for Travelers, Northern Italy and the third from Loy, the poet tellingly refuses the traditional feminine idealization of the place and name of Florence, rendering the “fairest flowers” of “la bella” as a “city with stones on the street.” Tara Prescott, in discussing textual links between Loy’s poetry and the Baedeker guide, speculates that Loy “hears Flora, the Roman goddess of spring and flowers, embedded in ‘Florence”; moreover, in “Giovanni Franchi,” she seeks to demythologize this association for the tourist in her own “imaginary guidebook” (21).

Shattering the mythic resonance of the feminized name and displacing it with a grounded materiality to represent women’s experience marks a primary thoroughfare distinguishing Loy’s poetic Baedeker of Italy, traversing a geography of gender in her poems of this period. Mapping this geography, the poems assume the en dehors garde position – rather than an avant-garde confrontation and conquest, the en dehors artist steps from and toward the outside, the margins, the peripheries to understand the lay of the land, not to conquer or relinquish it.

The Italian poems map a series of experiments as Loy creates her distinctive feminist poetics, an emerging en dehors garde that claims the margin and the outside as places of gendered insight. Her poetic Baedeker posits the woman poet differently from the confrontational militarism of the avant-garde, specifically manifested by Futurism in Florence. Her own awareness of her en dehors position – coming from the outside as a British woman observing Italian places and people, creating herself as a visual artist – informs her encounters with avant-garde formations in these Italian places.

Let us amble in this chapter through the stony streets of Florence and the Italian locales that Loy visited. Let us consider the tour as an en dehors garde experiment, linking place to an emerging feminist poetics