When Hitler curtailed the citizenship and rights of Jews through the passage of the Nuremberg laws (September 1935) and reoccupied the Rhineland in Spring 1936, Julien and Joella Levy became increasingly concerned about Mina Loy and her daughter Fabienne, given Loy’s partial Jewish heritage. In December 1935 Loy sent Fabienne to New York to live with Joella and Julien (Burke 386), and followed herself in late 1936. She would live in New York until 1953, when she moved to join Joella and Fabienne and their families in Aspen, Colorado. Loy would remain in Aspen until her death in 1966.

When Hitler curtailed the citizenship and rights of Jews through the passage of the Nuremberg laws (September 1935) and reoccupied the Rhineland in Spring 1936, Julien and Joella Levy became increasingly concerned about Mina Loy and her daughter Fabienne, given Loy’s partial Jewish heritage. In December 1935 Loy sent Fabienne to New York to live with Joella and Julien (Burke 386), and followed herself in late 1936. She would live in New York until 1953, when she moved to join Joella and Fabienne and their families in Aspen, Colorado. Loy would remain in Aspen until her death in 1966.

Although Loy had served as the Levy Gallery’s Paris agent, when she arrived in New York in 1936 she found that the Gallery didn’t need her help, a change in role exacerbated by Julien’s and Joella’s separation in 1938. Despite her earlier time in New York (1916-17, 1920-21), Loy felt (in her words) like “just another refugee” who had found herself “in a strange country” (Burke 387, 389): fifty-four years old and dependent on her daughters’ financial help and care, Loy’s youthful days in Greenwich village were a distant memory.

But Loy was not alone in making this journey: many artists and writers associated with the European avant-garde relocated to New York during World War II. A trans-Atlantic Surrealist scene flourished at Julien Levy’s and Peggy Guggenheim’s Galleries, and before long, a number of small galleries and little magazines dedicated to the work of the Surrealists had emerged.1 While Surrealism had exerted a powerful influence on American literary and artistic culture since the early 1920s, the presence of many European Surrealists in New York during World War Two lead to dynamic exchanges with American artists, poets, galleries and publishers, establishing Surrealism on firmer ground in American culture and invigorating the postwar U.S. avant-garde as poets and artists absorbed and transformed Surrealism.

Mina Loy is an important yet under-studied part of this history. Just as Futurism shaped her work well beyond her time in Florence, Loy’s critical transformations of Dada and Surrealism did not end with her move to New York in 1936. Scholars have emphasized Loy’s poverty, loneliness, and alienation in New York in the 1940s and early 50s, and at times have used Loy’s biography to support a reading of her late work as an epitaph to or commentary on the failure of an earlier European avant-garde moment and/or the failure of her own career.2

But this era was a vital one for Loy, involving an active working through of ideas and techniques that she had absorbed from the Futurists in Florence and from Dada and Surrealism in New York and Paris. As Linda Kinnahan discusses at length in her book Mina Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography, and Contemporary Women’s Poetry, Loy’s engagement with Surrealist documentary is a vitally important yet understudied feature of her 1940s and early 50s New York poetry and art, richly read alongside the photographs of Berenice Abbott, Clarence John Laughlin, and others:

A cluster of Loy’s late poems, written primarily during the 1940s and early 1950s while living in New York and focusing on the Bowery streets, fall outside of the oppositions between social art and experimental art, weaving together a form of urban documentary with inflections of Surrealist and Dadaist modes. […] In their attention to social issues of modern poverty, Loy’s Bowery poems stand in interesting parallel and relation to the ‘documentary impulse’ of the 1930s and its reliance upon the camera as a visual tool of social responsibility — a role for the camera that brought its own history to the documentary 1930s. Like the photographs of Berenice Abbott or the earlier Jacob Riis, Loy’s late urban poems join in a documentary effort to make the modern city visible to itself and to promote that visibility as a necessary commentary on socio-economic conditions, ideologies of progress, and histories of modern urban change. (Kinnahan 124)

In New York Loy would also continue to develop and transform her interest in the Surrealist found object and Surrealist poetics, in conversation with the work of “American Surrealist” Joseph Cornell (see “Sidewalk Surrealism”).

Loy’s assemblages and poems of this era reflect an artist working at the height of her powers, who was continuing to innovate in response to her environment. Her personal struggles with aging and poverty, coupled with her experience living near the Bowery, inflected her poetry and art with ethical vigor and spiritual reflection. Susan Dunn argues that “it is arguably the period of Loy’s most radical literary and visual production” (“Fashion Victims”), while Maeera Shreiber argues that Loy’s late New York poems “in the spirit of her very best works, compel us to seek out new frames of analysis as we rethink critical assumptions about femininity, about loss, and about Loy’s role in the reconstruction of modernist aesthetics” (482). Shreiber argues that “in taking the broken or aging female body as the site of illumination, Loy offers a powerful reconfiguration of the well-known association between women and lack, as well as making an importantly unsentimental claim for feminism and religion or spiritualism as complementary rather than adversarial discourses” (471).

Terrell Scott Herring has also developed relevant new frames of analysis in his study of Djuna Barnes’ unpublished late work created in Greenwich Village from the 1940s to the 1980s, arguing that it “constitutes a geriatric avant-garde that deepened her earlier investments in modernist aesthetics” (italics mine).3 Herring’s approach to Barnes invites a similar rethinking of Loy’s late work: both Loy and Barnes extended and transformed an understanding of modernist aesthetics and of the “en dehors garde” to encompass the experience of aging and dis-appearance.

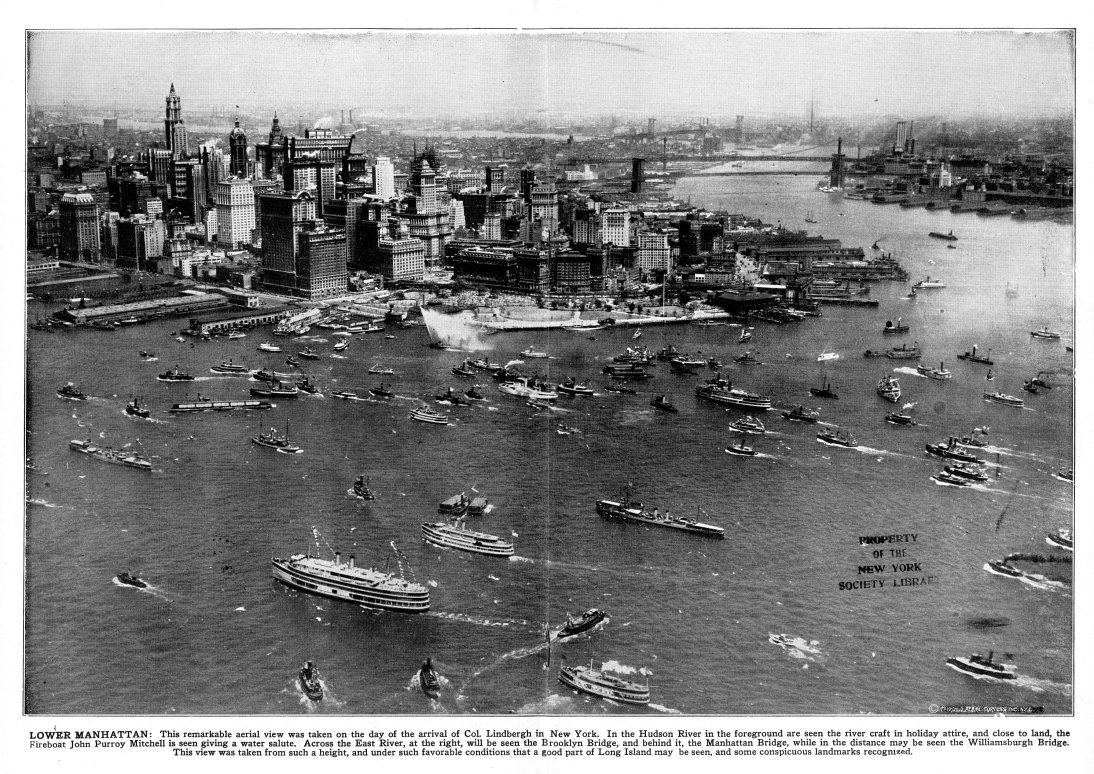

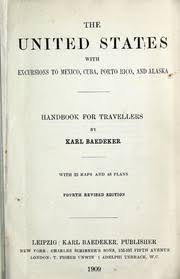

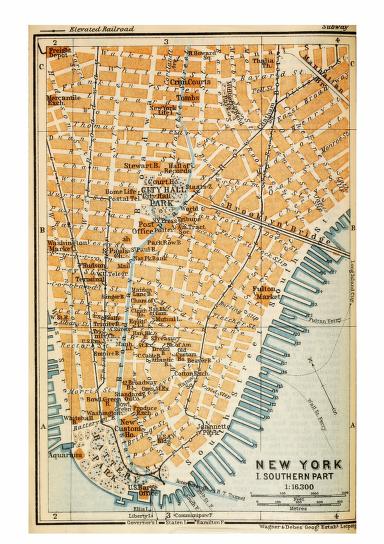

In Paris Loy had developed a feminist perspective on Surrealist artwork and the Surrealist movement through her paintings, objects, poetry, and fiction. Her critical framing of Surrealism in “Surreal Scene” and Insel countered Surrealism’s dominant narratives, gendered tropes, and claims to urban space, generating alternative exhibitions of Surrealism that explored spaces left out of the Paris Baedeker guide. In New York Loy extended her interest in the “museum without walls” (Malraux) while she deepened her criticism of those who “are looking for [their] canons of beauty in some sort of frame or glass case of tradition” (LLB82 297-8). Rejecting the “museums of the moon” that curated a narrow slice of “immortal” art and culture, and the official baedekers that guided tourists to places of cultural interest and value, she instead embraced the “flux of life” (LLB82 297-8) in the street, exploring an altered vision of everyday objects and scenes, and inviting critical reflection on how a culture’s “canons of beauty” are formed. More pointedly, Loy’s late art and writing constitutes a kind of anti-Baedeker, or rather a lyric Baedeker, a mobile museum built from ephemeral moments on streets overlooked by most guidebooks.4

This was the museum of the en dehors garde, and through it Loy defined a cultural space for her work. Despite her reclusiveness, Loy remained connected to other important artists, poets, and gallery owners in New York in the 1940s and 50s, resulting in the Bodley Gallery Exhibition of her “Constructions” in 1959 and in the publication of her second poetic collection, Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables by Jonathan Williams’ Jargon Press in 1958 (See “Collecting Mina Loy”). These two events echoed and amplified the verbal-visual, interdisciplinary aesthetics of Loy’s late work. In New York she published in Charles Henri Ford’s View in 1942 and 1945, helped Breton publish Arther Cravan’s previously unpublished Notes in VVV (no. 1 June 1942; no. 203 March 1943), and published new poems in Accent, New Directions, Partisan Review and Between Worlds (Burke 401-2; Januzzi, Bibliography 524-526).

Loy established or maintained important relationships with Joseph Cornell, Clarence John Laughlin, Julien Levy, Berenice Abbott, Frances Steloff, Charles Henri Ford, James Laughlin, Kenneth Rexroth, Marcel Duchamp, Peggy Guggenheim, Djuna Barnes, David Mann, Gilbert Neiman, Kenneth Rexroth, Henry Miller, and Jonathan Williams, among others (See “Bios”). Many of these figures, like Loy, were involved in the reception and transformation of Surrealism in the U.S. In these middle decades of the twentieth century Mina Loy was marginalized but not forgotten: while Loy suffered neglect when compared to her peers Marianne Moore and W.C. Williams, she also received significant moments of recognition. Loy had begun to establish the reputation and forge the relationships that would result in a small but influential group of admirers and her growing importance to a postwar, trans-Atlantic avant-garde.

In each stage of her career Loy continued to experiment and innovate: navigating her years in New York 1937-53 challenges conventional histories of the avant-garde and invites us to come up with fuller, more complex accounts of women’s contributions to this history. More pointedly, exploring Loy’s relationship to Dada, Surrealism, and even Futurism in her work of the 1940s and 50s clarifies the usefulness of the concept of the “en dehors garde.”

From Paris to New York: “On Third Avenue” (1942) and “Lunar Baedeker” (1923) Redux.

Loy would grapple with themes of anonymity, invisibility, and marginality in her 1940s and 50s poems, assemblages, and collages.5 Relevant to her own status as an aging female artist, these themes would allow her to explore her urban environment and the contradictions of American democracy in new and compelling ways. Loy became a U.S. citizen in 1946, and due to this formal identification with the U.S., she perhaps felt the ideals and pitfalls of American culture all the more keenly. The poet who had aligned free verse with American democratic experiment in her April 1925 essay “Modern Poetry” would in her later decades consider those who were marginalized or expendable in democracy, building poems and artwork from the refuse of postwar American culture.

Loy’s 1923 poem “Lunar Baedeker” mapped her modernist imagination, the poetic ability to critically filter and transform the real. Her 1942 poem “On Third Avenue” (as well as 1949’s “Hot Cross Bum”) revisit and revise the themes and urban imagery of “Lunar Baedeker,” providing a measure of the aesthetic distance Loy traveled from Paris in the early 1920s to New York in the early 1940s.

“On Third Avenue” begins with a statement in quotations:

“‘You should have disappeared years ago’–”

The speaker is not unidentified, and neither is the “you,” but several possibilities emerge as the poem unfolds:

so disappear

on Third Avenue

to share the heedless incognitoof shuffling shadow-bodies

animate with frustration (LLB96 109)

The moral judgment implied in the quoted phrase “should have disappeared” suggests that the “you” persists against all expectation, and despite the disapproval of the first line’s speaker. The poetic speaker, possibly distinct from the speaker of the first quoted line, responds: “so disappear…” The “you,” then, may refer to one of the many “shuffling shadow-bodies” on Third Avenue, one of the faceless urban crowd, or given the poem’s subsequent imagery, one of the impoverished, homeless men and women in lower Manhattan who would take center stage in “Hot Cross Bum” and “Chiffon Velours.”

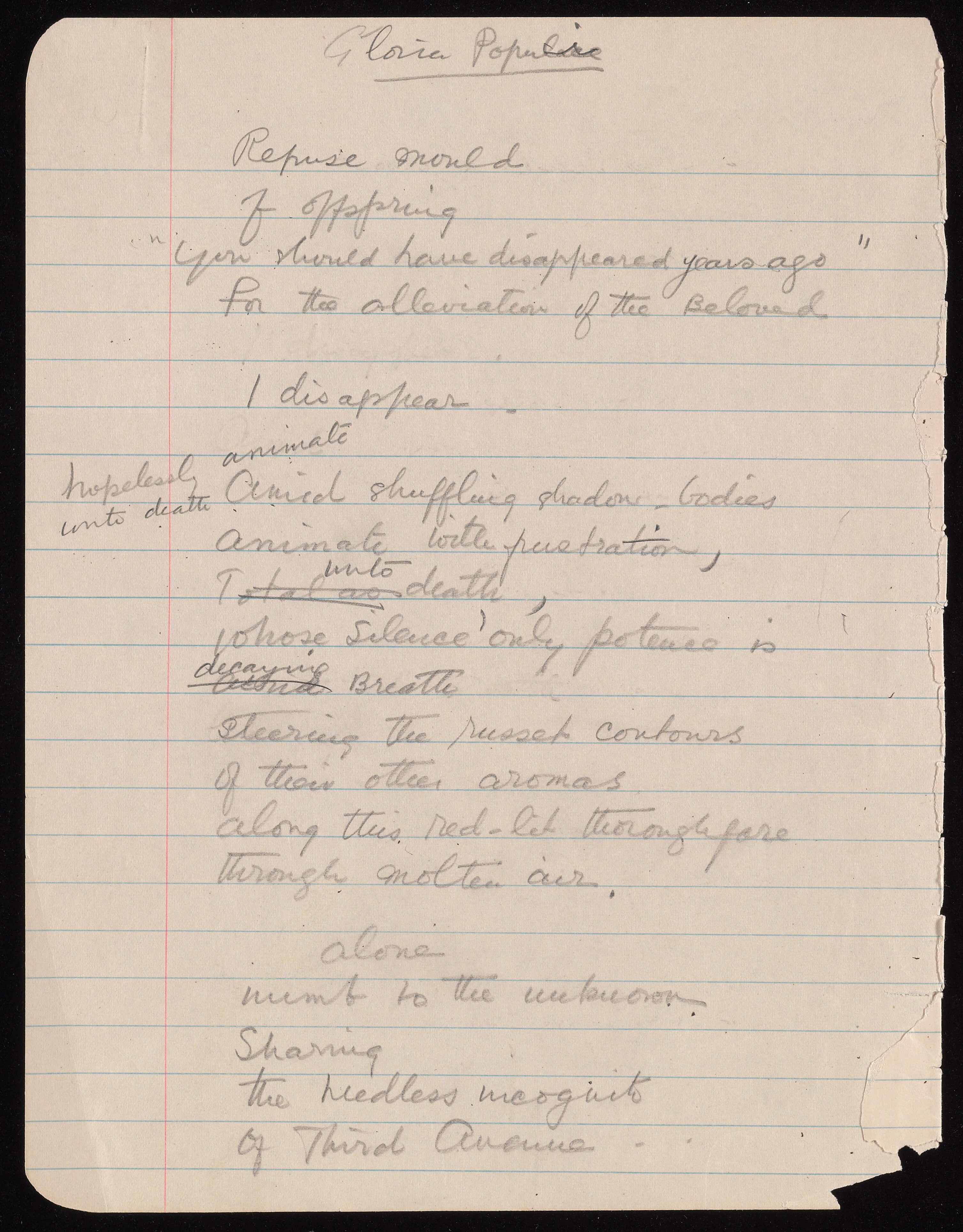

Loy typed and hand-wrote many drafts of this poem, which are housed in the Beinecke Library’s Mina Loy collection and are available in digital form. These drafts deserve careful study, with an early draft of the poem titled “Gloria Populi” revealing that the “you” may refer to the poet herself:

The draft begins:

Refuse mould

of offspring

“you should have disappeared years ago”

For the alleviation of the BelovedI disappear —

Amid shuffling shadow bodies

Animate with frustration,

unto death [….]

This draft suggests that the source of the opening quoted line is the poet’s disapproving offspring, and that the “you” is the poet, who responds, “I disappear / Amid shuffling shadow bodies.” While this draft reveals a personal conflict in the poem’s opening lines, tellingly Loy later revised the opening lines to obfuscate the quotation’s source as her “offspring” and the “you” as herself.

Changing “I disappear” to “so disappear” in later drafts allows the “you” to refer both to the poet and to any of the nameless “shadow-bodies” on Third Avenue. In turn, this change permits readers to imagine many possible speakers for the opening quoted line: the speaker could be Loy’s children; Loy herself (perhaps articulating a fear of how others perceive her, as a relic of an older avant-garde); any surprised or disapproving spectator; the disapproving voice of middle-class society that judges the homeless for their failure to meet American ideals of success, productivity, and progress; etc. Loy’s choice to change the line from “I disappear” to “so disappear” as she revised the poem signals that she moved outwards from the particulars of her own situation in order to enter and explore society’s “refused” population.6 This change also transforms a condition suffered (“I disappear”) into an imperative command (“So disappear”), empowering the speaker even as it points to her erasure.

If we read “On Third Avenue” as a self-reflexive investigation of a poetics grounded in an actual (versus a lunar) street, the poem constitutes Loy’s answer to the opening judgment — “You should have disappeared years ago” — by enacting a new kind of poetry that emerges when the poet disappears to share “the heedless incognito / of shuffling shadow-bodies” (LB96 109).7 In sharing the “heedless incognito” of lower Manhattan’s street population in this and other poems, Loy’s poetic speakers explore the trials of everyday survival in the city, as well as moments of what Breton called the Surrealist “marvellous,” as experienced by its poorest residents. Rather than use the lunar landscape to dislocate and transfigure the real, “On Third Avenue” locates what poet Elizabeth Bishop would call a “surrealism of everyday life” in urban streets rendered with documentary precision (Poems, Prose 860-1).

Loy describes the city in “Lunar Baedeker” as a “Necropolis” ( “a dead city, a city of the dead; a city in the final stages of social and economic degeneration” OED). As such, it comes into focus through visible absences, by the signs of what was once present, a city as seen in “a flock of dreams,” or dark negatives held up to the light. As discussed in “Criticism of Freud and Eros Obsolete,” Loy describes the lunar landscape as dry, bloodless, and infertile, an image of bodily absence that culminates in the lunar necropolis depicted as a museum:

And “Immortality”

mildews…

in the museums of the moon

“Nocturnal cyclops”

“Crystal concubine”

— — — — — — —

Pocked with personification

the fossil virgin of the skies

waxes and wanes— — — — (LB 82)

By placing “Immortality” in quotation marks, Loy treats the word like the title of a painting or artifact, and signals that ironically, judgments of a work’s immortality are contingent upon the museum’s claims to the permanent value of its collections. Works deemed “immortal” are thus, in fact, subject to history (mildew) and change. In the same manner, Loy subjects cliched personifications of the moon — “Nocturnal cyclops” and “Crystal concubine” — to the time and change that museums resist. Loy’s poetic baedeker juxtaposes human museums (which claim to permanently house works of “immortal” value), with the relatively unknown history of the moon, which in 1923 eluded human efforts to traverse, represent, or possess it. Loy’s line of dashes that concludes the poem gestures to this failure of representation, and perhaps to the disfiguring personifications of literary tradition, but also visually opens up space, creating a pathway for new understandings.8

As “Lunar Baedeker” provides an imaginary, poetic “tour” of the moon, and alludes to the human cities that shadow it, the poem becomes an anti-Baedeker, a guide to human pretensions to knowledge and immortality embodied by the institution of the museum, and similarly, by the Baedeker guidebooks that chronicle a city’s cultural treasures and curate its urban geography for visitors.9

Loy conducts a similar tour in “On Third Avenue,” but bodies are all too present, “animate with frustration,” vessels of suffering and decay. Rather than moving through the “eye-white sky-light / white-light district / of lunar lusts” lit by “Stellectric signs,” these shadow-bodies move “through the monstrous air / of this red-lit thoroughfare,” while “saturnine / neon-signs / set afire / a feature / on their hueless overcast / of down-cast countenances” (LB96 81, 109). This dark landscape lit by a fiery neon red connotes not the ‘red-light district” but the agonies of hell.

While “Lunar Baedeker” invokes dreams and cocaine as agents of vision, and harnesses natural and celestial sources of illumination (“Lucifer” the morning star; “infusoria,” microscopic organisms found in decaying organic matter; “stellectric signs” suggesting a merging of stars and electricity), “On Third Avenue” limits itself to human sight and the man-made illumination of “neon signs.” This is what Walter Benjamin in his discussion of Surrealism termed “profane illumination,” a “materialistic, anthropological inspiration” which he contrasted to “religious ecstasies or the ecstasies of drugs” (Reflections 179). Although the “shadow-bodies” are materially present, they seem to literally ‘disappear” into their dark environment, hovering on the edge of visibility. Unable or unwilling to meet the eyes of others, the impoverished figures remain faceless, abstract rather than particularized, a “feature” visible only “here and there” as the neon catches it. Or as Benjamin stated, “no face is surrealistic in the same degree as the true face of a city” (Reflections 182), and Loy’s poem shades in that face.

Loy tellingly uses the language of art (sculpture and cinema) in her depiction of these figures: even as they refuse to meet the speaker’s eyes , they invite the poet’s transformative vision.

For their ornateness

Time, the contortive tailor,

on and off,

clowned with sweat-sculptured cloth,

to press

upon the irreparable dummies

an eerie undress

of mummies

half unwound. (LB96 109-110)

Likening the vagrants to tailor’s dummies, Loy reflects with irony on how time and sweat resulting from the effort to live on the urban street, “sculpt” the clothing of the homeless. Susan Dunn suggests that the poem depicts the “salvages of the garment industry” in lower Manhattan, and alludes to its sweat shops (“Fashion Victims”). This sculpture is an “art” not just found in but fashioned by living in the street. The final image of mummies half unwound evokes a gothic scene from a horror film, the undead “shuffling” down the streets of lower Manhattan and literally disappearing as they fall apart.10

While the first section of the poem depicts the liminal state that results from the injunction “so disappear”, the second section reflects on what can be seen and gained through the speaker’s “disappearance” into the shadow-bodies of Third Avenue. The speaker twice begins, “Such are the compensations of poverty, / to see——–” and the descriptions of the urban scenes that follow this refrain are akin to photographic snapshots (Kinnahan 141), arrested moments in the dynamic, changing “museum” of the street. Loy’s speaker finds aesthetic value in objects and scenes which are human, mutable, and fleeting, the antithesis of the “museums of the moon”:

Like an electric fungus

sprung from its own effulgence

of intercircled jewellery

reflected on the pavementlike a reliquary sedan-chair,

out of a legend, dumped there,before a ten-cent Cinema,

a sugar-coated box-office

enjail a Goddess

aglitter, in her runt of a tower,

with ritual claustrophobia. (LB96 110)

Loy describes a Cinema box-office in a series of similes that transform it into an “electric fungus / spring from its own effulgence,” into a “reliquary sedan-chair / out of a legend”, and finally, into a tower that imprisons a Goddess, the cinema attendant. Through these similes, super-imposed upon the actual box office, Loy draws attention to the incongruity of the gritty street and its realism juxtaposed with the “sugar-coated box-office” and the “ten-cent” fantasies it peddles. The box office, like the poem, mediates reality and unreality.11

In contrast to escapist cinema, however, Loy’s mini-surrealist film constructed from this sequence of juxtaposed images allows the street to become its own cinema, redolent with irony, an unfolding space for chance visions:

Such are compensations of poverty,

to see ——-Transient in the dust,

the brilliancy

of a trolley

loaded with luminous busts;lovely in anonymity

they vanish

with the mirage

of their passage. (LB 110)

The “luminous busts” connote the grandeur and memorializing function of the museum, yet they are located anomalously in a trolley, the mystery of this juxtaposition left unexplained. Tara Prescott suggests that Loy may describe the literal movement of busts in a trolley, or more abstractly, “the upper halves of commuters, seen through trolley windows” on the Third Avenue El train (182, 203). The beauty of this scene lies not only in the juxtaposition of busts and trolley but in their movement and subsequent vanishing.12 Loy chooses the word “mirage” to convey the effect of the trolley’s appearance and disappearance: a “mirage” refers to a visual illusion generated by atmospheric conditions. At stake in the mirage is the surrealist relationship between the real and the unreal, everyday life and art: attuned to such “found juxtapositions” the poet becomes a conduit for the Surrealist “marvellous,” discovered on the city sidewalks.

If “Lunar Baedeker” uses the moon to displace, distort and crticially transform Loy’s experience of cities such as Paris, New York, and Berlin (and their avant-gardes), her Bowery Baedekers instead are located precisely and concretely in lower Manhattan, finding moments of the unreal and surreal erupting from the ordinary.

In other poems such as “Ephemerid” Loy is critical of her own tendency to transform the ordinary, factual events of the street into the unreal or fantastical, and many of her poems from this time probe the ethics of the poet’s use of her found images, subjects, and materials. As Linda Kinnahan discusses at length in Mina Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography, and Contemporary Women Poets, such questions were central to the “surrealist documentary” project that compelled Loy and photographers such as Berenice Abbott, a friend of Loy’s from her time in Greenwich Village and Paris.13 Loy’s interest in invisibility and anonymity would resonate with her efforts to make visible lives that were ignored and erased, and she would harness surrealist techniques in her effort to reveal and ironize the features of postwar consumer society that rendered democratic freedoms questionable. In an ethical adaptation of the Surrealist image, Loy would attempt to juxtapose “penury / with dream” (“Ephemerid” LB96 118).

Refusées

Beyond a hell-vermilion

curtain of neon

lies the Bowery (LB96 133)

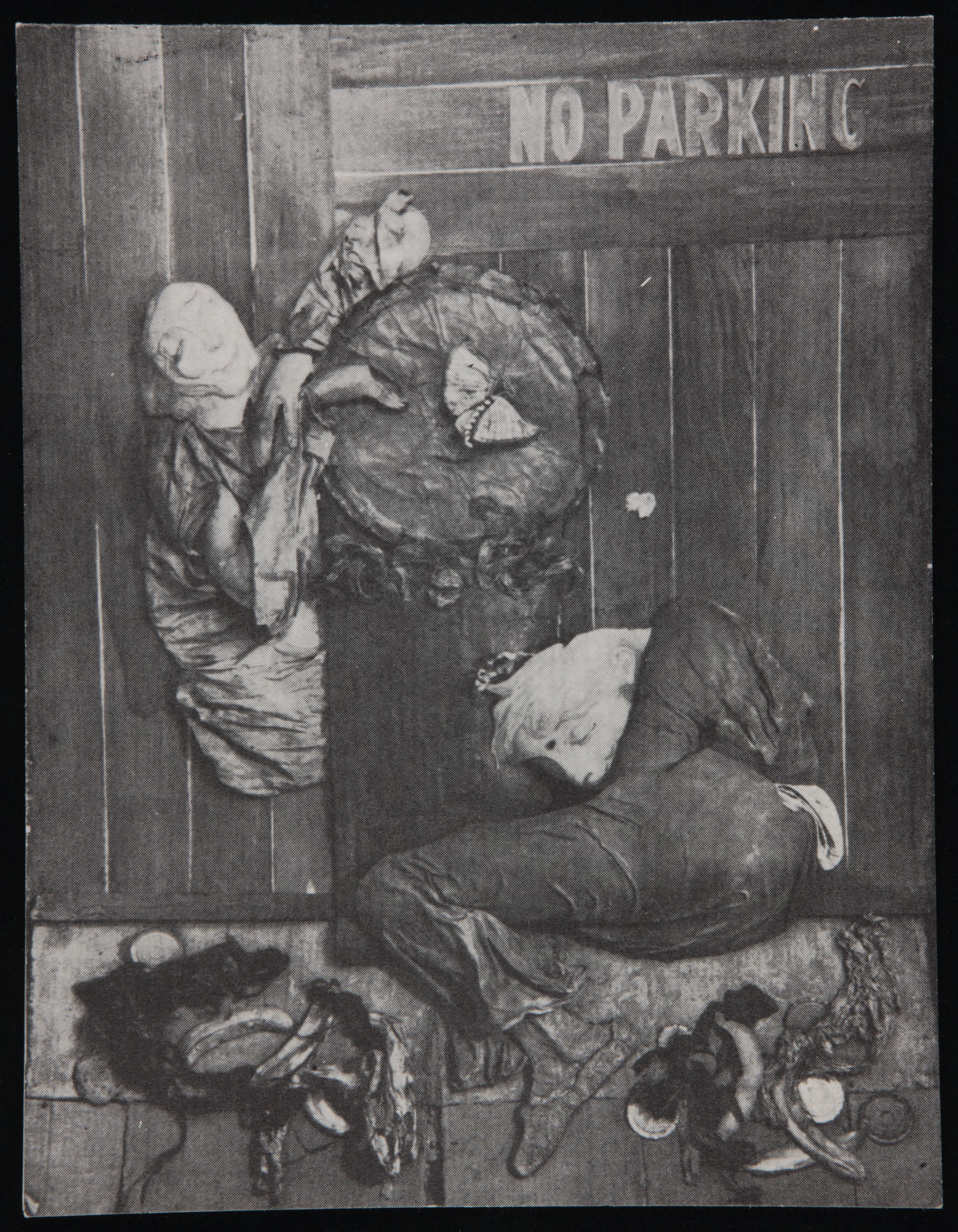

Mina Loy opens the curtain on her poetic tour of the Bowery, “Hot Cross Bum,” with a nod to the area’s rich nineteenth-century theatrical history, and to its subsequent “celebrated degeneration” (New York City Guide, 119).

The Federal Writers Project New York City Guide (1939) described the Bowery as “fixed […] forever in the Nation’s consciousness as a place of unspeakable corruption”:

The Bowery today is chiefly given over to pawnshops, restaurant equipment houses, beer saloons, and miscellaneous small retail shops. Here flophouses offer a bug-infested bed in an unventilated pigeonhole for twenty-five cents a night, restaurants serve ham and eggs for ten cents, and students in barber ‘colleges’ cut hair for fifteen cents. Thousands of the nation’s unemployed drift to this section and may be seen sleeping in all-night restaurants, in doorways, and on loading platforms, furtively begging, or waiting with hopeless faces for some bread line or free lodging house to open. No agency, at present (1939), provides adequate food, shelter, and clothing for these wanderers. Missions furnish food and lodging for a few, and try by sermon and song to touch the souls of the down-and-outers and the sympathies of generous tourists.

Through its association with the homeless and unemployed, the Bowery had become a perverse tourist site, a fact Loy acknowledges in “Hot Cross Bum”:

for your loafing

is the fashionconditional compassion:

appreciation

of your publicity value

to the Bowery (LB96 137)

Excavating the forces that shape the Bowery and the predicament of its bums, Loy’s late work challenges the “conditional compassion” of the tourist’s gaze and probes the bums’ status as unwitting “actors” in a public spectacle.

Trash — and its removal — serves as a central metaphor and literal material for Mina Loy’s Bowery Baedekers, as a passage from “Hot Cross Bum” makes clear:

Collecting refuse more profuse than man

the City’s circulatory

sanitary apostles

a-leap to ash-cans

apply their profane ritual

to offalDust to dust

Even a putrescent Galaxy

could not be left where it lay

to disgust

scrapped are remains

empty cans remain. (LB96 142-3).

Empty garbage cans serve as the counter-balance to “Lunar Baedeker’s” “museums of the moon”: while the museum confers value, significance, and even “immortality,” the empty garbage can signifies the cultural effort to erase from sight and memory all that threatens its values. “Lunar Baedeker”‘s “ecstatic dust” becomes an all too-human “putrescent Galaxy” that generates “disgust.”14 Drawing attention to the processes of moral and aesthetic hygiene she witnessed on the streets of Lower Manhattan, Loy maps in her poetry and artwork an alternative role and space for art, that of the en dehors garde. Notably “en dehors” can refer to “outside” as in “en plein air,” out in the air, on the street.

While living in lower Manhattan, Loy created a remarkable series of constructions inspired by the homeless men and women she encountered on the Bowery (See “Mina Loy, Bowery Construction”). Carolyn Burke suggests a critical engagement with the avant-garde (specifically Picasso, Duchamp, and Cornell) at work in Loy’s choice to use actual trash as the material for these assemblages, observing that “Mina brought to her shabby materials an acute sense of the cost involved for those who searched the garbage cans: rather than posing as outsiders, as the avant-garde had done, they actually lived at the bottom of the heap” (420; see also Carolyn Burke’s essay “Mina Loy & Househunting, or Biography as Restoration”). Loy called the series of assemblages she made Refusées, which Carolyn Burke describes as a “punning blend of refuse, Refusés, and refugees, which summed up her long itinerary from West Hampstead to the Bowery” (420).

Sensitive to the experience of poverty, anonymity, and neglect, Loy was able to bring to the en dehors garde position of “outsiderdom” a lived sense of “the cost involved.” While anonymity was not simply Loy’s choice at this time, and likely caused her personal suffering, in its guise Loy deepened and transformed her modernist project in Lunar Baedecker (1923) by adapting it to the Bowery, reflecting on the suffering and resilience of those who live outside “the museums of the moon.”

More pointedly, ”On Third Avenue” brings to fruition a democratic understanding of modernism that Loy had first articulated in Paris in her 1924 appreciation of Gertrude Stein:

The pragmatic value of modernism lies in its tremendous recognition of the compensation due to the spirit of democracy. Modernism is a prophet crying in the wilderness of stabilized nature that humanity is wasting its aesthetic time. For there is a considerable extension of time between the visits to the picture gallery, the museum, the library. It asks ‘what is happening to your aesthetic consciousness during the long intervals?’

The Flux of life is pouring its aesthetic aspect into your eyes, your ears – and you ignore it because you are looking for your canons of beauty in some sort of frame or glass case of tradition. Modernism says: Why not each one of us, scholar or bricklayer, pleasurably realize all that is impressing itself upon our subconscious, the thousand odds and ends which make up your sensory every day life. (LLB82 297-8)

History & Maps of the Bowery: Web Resources

- Eric Ferrara, “LES History: A Look Back at the Bowery ‘Blue Book'” The Lo-Down

- Documentary trailer: The Bowery, a film by Eric Ferrara and Rob Hollander (LES history project)

- Russel Crouse, “Bowery Bum,” The New Yorker October 31, 1931, p 23

- 1956 Historic Footage of the Bowery

- Map of the Bowery

- James Nevius, “The Ever-Changing Bowery” (Curbed NY, October 4, 2017)

- Historical and Cultural Significance of the Bowery (The Bowery Alliance)

- Researching New York City Neighborhoods (New York Public Library guide)

- On the Surrealists in New York during World War Two, see in particular the studies by Martica Sawin, Dickran Tashjian, Jed Perl, and Sandra Zalman. On Surrealism in American little magazines see Tashjian, Boatload; Rosenbaum, “Exquisite Corpse.”

- For instance Amy Morris argues that “Mina Loy failed to ‘institutionalise’ her work at a crucial moment, and became instead a marginal figure” (82). Morris argues that “her [Loy’s] identification in later poems with ‘common’ suffering expressed Loy’s internalisation of her cultural submergence” (82). Morris cautions readers from claiming Loy’s “marginal self-positioning as chosen and defiant” (82), writing, “it would be wrong to celebrate a marginality that was ordained by circumstances, just because the author managed to respond creatively from the sidelines on which she had been forced to stand. Loy’s manuscript archive from the 1940s shows her crafting poetry out of negative emotions and a painful lack of self-esteem” (83).

- Herring notes that “Archived documents record the elderly writer performing the principles of high modernism—innovation, experimentalism, and novelty—across an unprecedented array of genres, such as the poem, the pharmacy order, the grocery list, the medicine regimen, the memo, and personal correspondence.”

- One of the key guidebooks published around the time of Loy’s return was the 1939 New York City Guide sponsored and published by the Federal Writers Project. This guidebook contains a section on the Bowery (p. 119-121, excerpted in this section) that addresses the problem of homelessness.

- According to Carolyn Burke’s biography, Loy lived on 13th Street near Union Square from 1941-44. Thus she was close to 3rd Avenue, which as it continues south, turns into the Bowery. The 3rd Avenue Elevated train ran over the Bowery until it was taken down in 1956. In 1948 Loy moved to 2nd Street, then later that year to Stanton Street, where she lived until she moved to Aspen.

- Deirdre Egan also argues that the drafts of the poem “confirm a link between the poet and her down-and-out subjects” 982.

- Loy scholars have provided excellent readings of this poem and the new kind of poetry that it explores; see in particular the discussions by Maeera Schreiber, Linda Kinnahan, Deirdre Egan, and Tara Prescott.

- The moon, a “fossil virgin” conventionally feminized in the poetic tradition, is “pocked with personification,” the visual “pocking” of Loy’s line of dashes dramatizing the defacement of personification.

- For instance “Peris in livery” alludes to fairies or elves barred from Paradise dressed in livery or servant costumes, but also puns on “Paris in livery,” while “Wing shows on Starway” alludes to Broadway and its stars or celebrities, subtly suggesting the cities that informed Loy’s lunar invention.

- Loy may have had in mind the 1932 film “The Mummy”; “The Mummy” had no official sequels, but rather was reimagined in The Mummy’s Hand (1940) and its sequels, The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944), The Mummy’s Curse (1944),] Loy’s interest in horror films and mummies specifically is apparent in the novel Insel, when Loy’s protagonist Mrs. Jones states that Insel “reminded one of those magically animated corpses described by William Seabrook” (51); to help Insel with “money-making devices” Mrs. Jones suggests that “the most practical [was] to star him in a horror film” (76).

- Loy like Cornell was drawn to popular entertainments and film and created “museums” of the street that had much in common with lower Manhattan’s dime museums and wax museums. Tim Armstrong suggests that the “sugar-coated box-office” “is a less than celebratory image: indeed it would be quite easy to read these lines as [an] indirect critique of Cornell and his rituals of enclosure” (Salt 207-208).

- Maeera Shreiber reads this interest as continuous with Loy’s “life-long spiritual quest” (469); thus, “Loy’s visions are as much concerned with what is concealed as with what is revealed” (474). This spiritual quest would inform her dialogue with the work of Joseph Cornell and her late assemblages and poems.

- See in particular Kinnahan’s detailed, insightful discussion of Loy’s Bowery poems and Abbott’s photography in Chapter 3, “Portraits of the Poor: The Bowery Poems and the rise of Documentary Photography.” Kinnahan notes that both Loy and Abbott pursued a “poetics of urban documentary” that involved “building individual images into a kind of ‘multifaceted but unified totality'” (134). Abbott’s 1939 collection Changing New York (1939) “chimes with Loy’s late Bowery poems […] grouped as a series she entitled ‘Compensations of Poverty'” (134). Both poet and photographer share “serial tactics of juxtaposition, framing, and perspective” and often employed these techniques to capture “surreal looking displays” (138, 139).

- “Dust to dust” alludes to the Burial Service from the English Book of Common Prayer, and emphasizes mortality and bodily “remains,” which are ironically “scrapped,” Loy’s punning play with “remain” and “scrap” indicating both the remnants of the body and the cultural desire to erase them.