This section provides a brief history of Paris Dada and Surrealism and contextualizes Mina Loy’s engagement with these movements, while the section Surreal Scene considers how Loy and other women critically transformed Surrealism through their art and writing. In this section, you can explore Loy’s relation to:

- Paris Dada

- The Surrealist Movement

- The Surrealist Movement’s treatment and depictions of Women

- Women & the Surrealist Movement

- Negrophilia, Négritude, Afro-Surrealism

Boxing Rings: Surrealism Emerges from Paris Dada

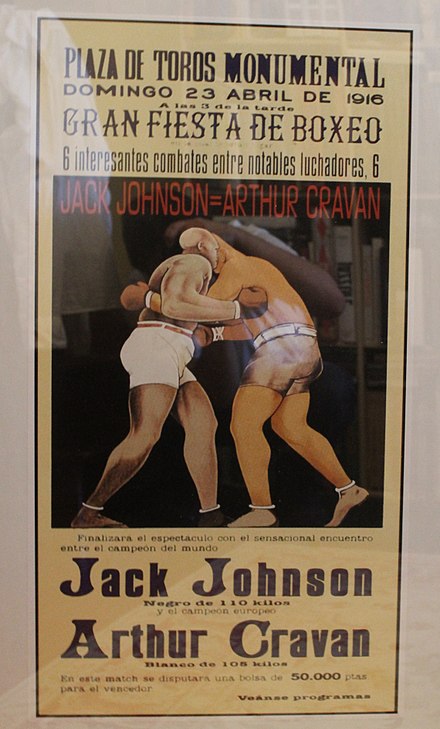

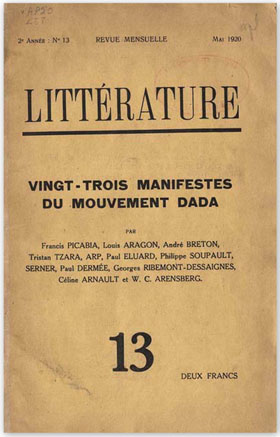

When the New York Dada circle dispersed in 1921, Duchamp and Man Ray returned to Paris, joining a vibrant Dada scene. Tristan Tzara’s arrival from Zurich in January 1920 provided the spark that ignited Paris Dada: he joined Francis Picabia (whom he had met in Zurich), as well as the poets André Breton, Philippe Soupault, and Louis Aragon, who together edited the journal Littérature (Rasula, Destruction 169-175). Due to struggles for leadership over the direction of Paris Dada (particularly between Tzara and Breton), and the difficulty of organizing a movement with such a resolutely anti-programmatic agenda, the Paris Dada group quickly splintered (Rasula, “Introduction” and Chapter 9, Destruction), ending in a literal fist fight at a performance on July 6, 1923 (Rasula, Destruction 196). This end was in keeping with the Dadaist embrace of boxing and boxers, and embodied the adversarial, pugilistic stance of the avant-garde.

Mina Loy moved to Paris in Spring 1923, so was present for the demise of Paris Dada and the beginning of the Surrealist movement, marked by the October 1924 publication of André Breton’s first Surrealist Manifesto. Most figures involved in the Surrealist movement had been involved in Paris Dada. Breton’s and Soupault’s 1919 publication of The Magnetic Fields, a collaborative text produced through techniques of automatic writing, was considered by Breton as the first Surrealist work, reflecting the significant overlap of artists, ideas, and techniques between the two movements.1

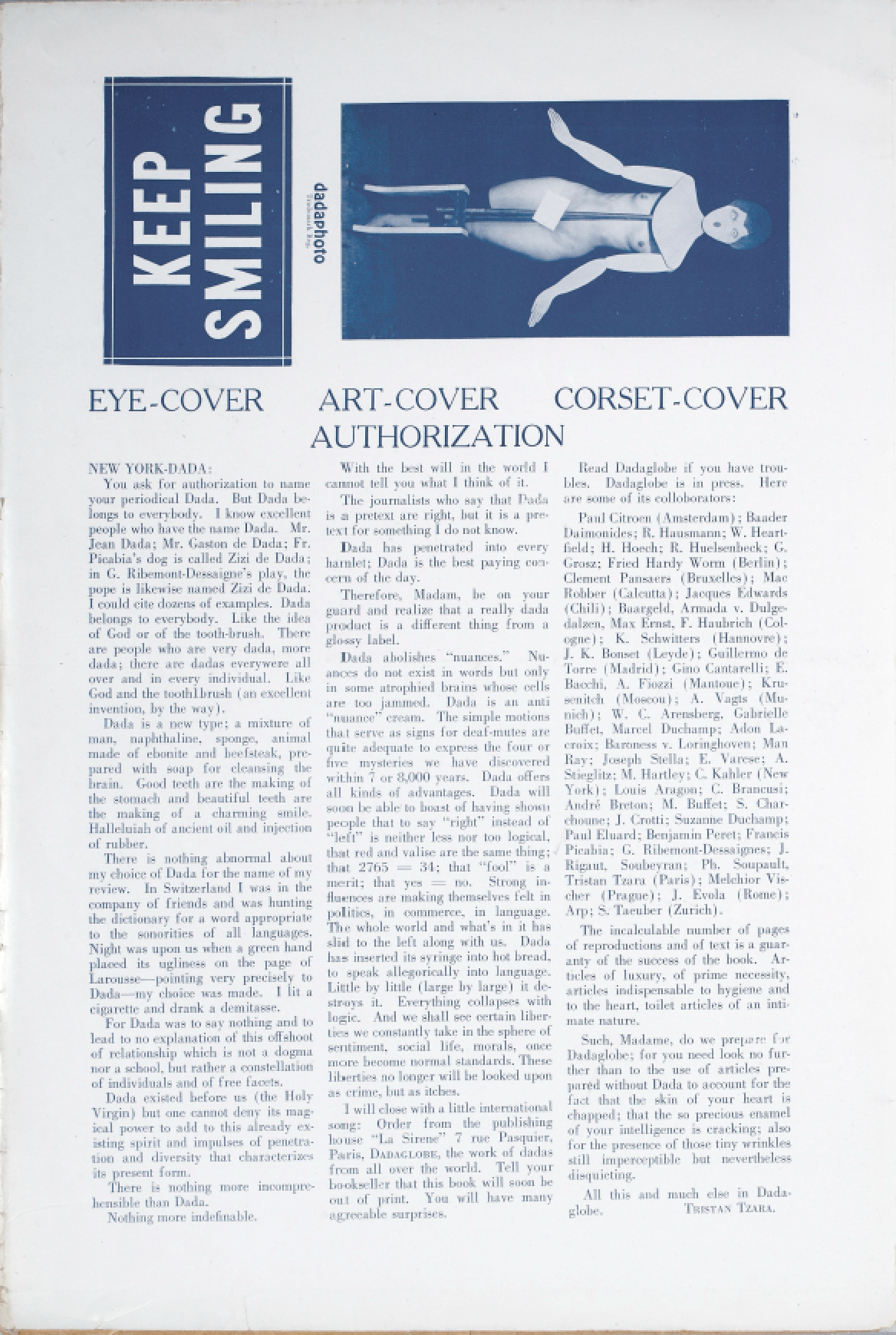

Loy had certainly heard about Paris Dada while living in New York (Burke 283). Duchamp’s and Man Ray’s little magazine New York Dada (April 1921) which appeared prior to Loy’s departure for Europe in Summer 1921, contained a letter from Tristan Tzara which stated that Dada “is not a dogma nor a school, but rather a constellation of individuals and of free facets.” Tzara included both Loy and Arthur Cravan in that constellation, listing them among the English-speaking Dadaists (Burke 283), and as photos from early 1920’s Paris demonstrate, Tzara and Loy moved in similar circles. In 1927, Tzara would write the essay for Laurence Vail’s exhibition held at Mina Loy’s Lamp Shop (the “Galeries Mina Loy”) (Burke 342).

While Loy had absorbed Dadaist ideas and techniques in New York and briefly “Danced Dada”, she remained on the group’s margins: like the Baroness Elsa, Loy’s feminist perspective fueled her engagements with Dada. As Naomi Sawelson-Gorse argues, for all their dedication to rebellion, male Dadaists “maintained the status quo of the patriarchal socio-cultural judgments and codifications regarding gender of the late nineteenth-century bourgeois society in which they were born, and, in most instances, of Catholic upbringings” (“Preface” Women in Dada xii). Women gained entry to the Dadaist constellation as “Dada’s Mamas, a male artist’s muse, sexual partner, sometimes even wife” (Sawelson-Gorse, Women in Dada xii-xiii). Loy and the Baroness, who resisted subservient roles, were not easily assimilated to Dada, even as the Baroness in John Rodker’s summation “dresses dada, loves dada, lives dada” (Burke 288), and as Irene Gammel writes, was “the embodiment of dada in New York” (Baroness 10).2

Man Ray and Duchamp included Loy (and alluded to her connection to Arthur Cravan) in New York Dada, describing her as a hostess-organizer of a “coming-out party,” a “grand socking cotillion” for the “Pug Debs” (pugilistic debutantes) Marsden Hartley and Joseph Stella at Madison Square Garden. They wrote, “Before the pug-debs are introduced, Miss Loy will turn a gold spigot and flocks of butterflies will be released from their cages.”

Loy-as-hostess is to a certain extent defined by her femininity in this representation of the pugilistic or “pug” avant-garde, culminating in her release of the butterflies. On the other hand Loy had clearly gained the Dadaists’ respect, perhaps due to her ability to spar creatively and romantically not only with Cravan, but with the Futurists Marinetti and Papini. Like the “pug debs” whose attire bridged the boxing ring and society salon, and incorporated both masculine and feminine elements (bejewelled slippers, velvet gloves, silk shorts), Loy’s release of butterflies at the boxing ring suggests that she too possessed both masculine and feminine qualities, and challenged conventions of gender in Dadaist fashion.3 Boxing permitted fighters of different races to meet on equal ground, as in the match between Jack Johnson and Arthur Cravan. Although New York Dada‘s depiction of Loy as “hostess to a boxing match” kept her out of the boxing ring, she had been allowed a role and ring-side seat at this Dadaist soirée. This position –at once privileged and marginal — would shape Loy’s en dehors garde response to the “pugilistic” avant-garde.

As the Dadaists-turned-Surrealists mythologized Cravan and extended his legend, Loy would become increasingly irked, especially by theories of Cravan’s disappearance that suggested he sought to escape his marriage to Loy and which implicitly cast Loy as the entrapping, pregnant wife (Burke 284, 286, 301, 381). As Sandeep Parmar argues, in Loy’s unpublished autobiographical narrative Colossus, likely begun in the early 1920s, Loy counters the mythologizing of Cravan by presenting her own “posthumous myth” of Cravan not as proto-Dadaist but as the “father of modernity” (Jacket 34). Loy would comment in the 1930s,

Talking of Cravan – nothing would have enraged him more than to be appropriated by the Surrealists – But there is no denying that they ‘have raisons’ somehow or other – La Bête Noir reprinted one thing of his the other day and I noticed at once how extraordinarily it anticipated Surrealism. Only the approach was entirely different. C. got the most bizarre antitheses through the mere expression of his direct reactions as a simple living entity – he had no theories – except the conviction of his superiority over the rest of mankind. I remember discussing Freud with him – thinking him (F) then a great man. Cravan said no – They have showed me. (Carolyn Burke Collection on Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. YCAL MSS 778 Box 1.4

Loy’s comment illuminates Cravan’s creative inclinations, and provides subtle insight into her own. Cravan didn’t intend to produce “Surrealist” juxtapositions: his “bizarre antitheses” were a product of a creative sensibility responding to modern life, not an intentional result of a Surrealist theory. Loy positions Cravan as an individualist guided by a conviction of his “superiority over the rest of mankind,” who would resent appropriation by any group or movement. These comments also characterize Loy. Her “pig cupid” from “Love Songs” published in Others in 1915 would reverberate throughout the twentieth century as a striking “anthesis” that anticipated the Surrealist image, and Loy’s conviction of her native superiority was evident in her poem “Apology of Genius,” published in Lunar Baedecker (1923).5

Thus as French Surrealism emerged from Paris Dada in 1924, Loy was an interested, if skeptical, spectator. She would soon become immersed in the Surrealist scene.

André Breton and the Surrealist movement

Surrealism in Paris was most forcefully articulated by poet André Breton, its founder and de facto leader, dubbed the “pope” for his careful policing of the movement, including his habit of publicly breaking with or expelling those who disagreed with his ideas.6 While working as a medical orderly in the French army during World War One, Breton treated psychiatric patients and became interested in Freud’s ideas. Whereas Dada was occasioned by the horror and irrationality of World War I, Freudian thinking about irrational desires would prove central to Bretonian Surrealism.

As articulated by Breton in his writing of the 1920s and 1930s, Surrealism was devoted to expressing in conscious life the workings of the unconscious mind. In his first Surrealist Manifesto (1924), Breton defined surrealism as: “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern” (Manifestoes 26).

Breton’s interest in automatism — the uncensored expression of unconscious thoughts, wishes, desires — exemplified the surrealist search for an imagination freed from “a state of slavery” (Manifestoes 4) induced by the “absolute rationalism” and “reign of logic” in twentieth-century culture (Manifestoes 9). Like Freud, Breton explored “the omnipotence of dream” and other forms of thought unconstrained by reason (Manifestoes 26).

Freud sought a therapeutic outcome in the conscious recognition of unconscious wishes and desires, and often analyzed dreams to this end. Breton conversely sought in dreams a deepened perspective on and experience of the real: “I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak” (Manifestoes 14). For Breton, the bringing of dreams and dream-like states into conscious life could alter an experience of reality.

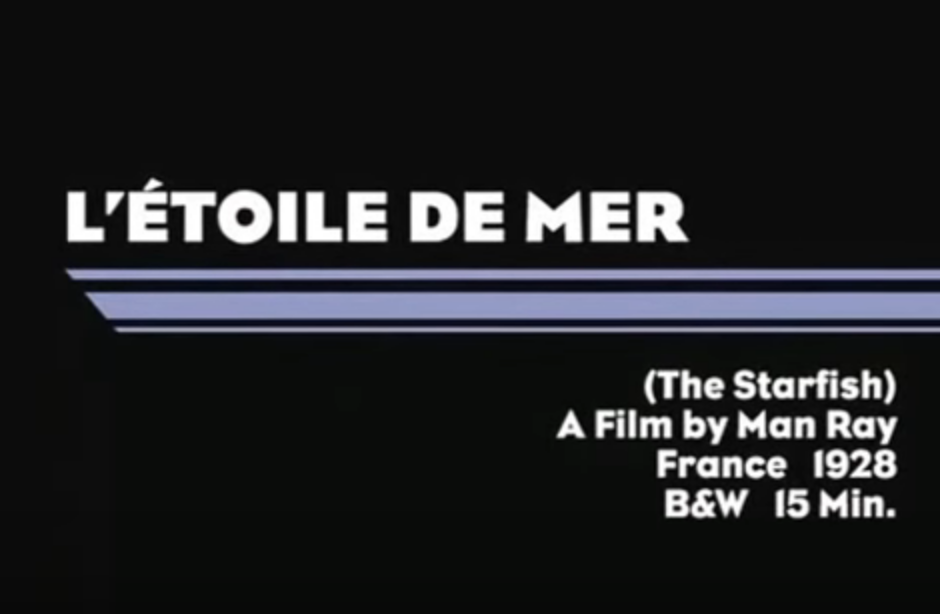

Poetry was the means of this dialectical resolution of opposed states, the first step towards a broader social, political, and economic revolution. With his roots in Dada, Breton did not limit poetic creation to a particular genre, but understood it as a way of knowing, its value located in its capacity to realize a surreality. As Tzara put it, “Life and poetry were henceforth a single indivisible expression of man in quest of a vital imperative” (Motherwell 406). A film or painting could participate in the poetic act of commingling dream and reality as much as an essay or poem, and generic experiment and collaboration were a natural outgrowth of this understanding. Film closely approximated the visual irrationality of dreams and was a favored medium of the surrealists, as in Salvador Dali’s and Luis Bunuel’s 1929 film Un Chien Andalou or Man Ray’s L’Étoile de Mer (1928).

Automatic writing and painting, collaborative games such as the exquisite corpse (created by each participant adding writing or part of an image and folding the paper to hide their contribution), and chance operations were all techniques used by the Surrealists to facilitate unconscious expression. Decentering the romantic notion of the artist as an autonomous originator, the Surrealists instead regarded the poet as a “modest recording instrument” (Manifestoes 28). This was a democratic, even radical understanding of poetry: building on Lautreamont’s statement that poetry should be made by all, Breton said that he wanted “to put [poetry] within reach of everyone” (Manifestoes 37). Breton noted “The freedom [surrealism] possesses is a perfect freedom in the sense that it recognizes no limitations exterior to itself. As it was said on the cover of the first issue of La Révolution Surrealiste, ‘it will be necessary to draw up a new declaration of the Rights of Man’” (This Quarter 22).

The incongruity between the unconscious and conscious states of mind served as the central formal principle of Surrealist work, and was conveyed through the juxtaposition of discordant elements, often meant to shock the reader or viewer. Dadaists had developed the technique of juxtaposition through collage, with Max Ernst a key figure whose collages bridged Dada and Surrealism. Breton explained this principle of juxtaposition through Reverdy’s definition of the image:

“The image is a pure creation of the mind. It cannot be born from a comparison but from a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be – the greater its emotional power and poetic reality…” (Manifestoes 20).

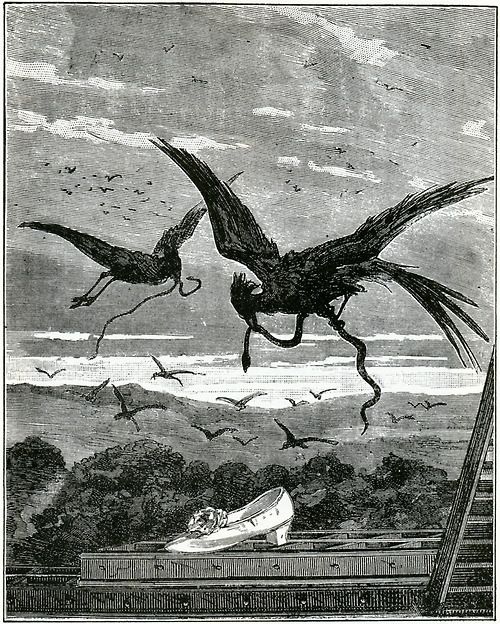

Reverdy and the Surrealists took inspiration from Lautréamont’s celebrated comparison of beauty to “the chance meeting upon a dissecting table of a sewing-machine with an umbrella,” which Max Ernst paraphrased as “the fortuitous encounter upon a non-suitable plane of two mutually distant realities” (This Quarter 8). Ernst’s collage from Une Semaine de Bonté below demonstrates this technique: he has juxtaposed a woman’s shoe with birds holding snakes, against the backdrop of a wooden platform inexplicably set in nature, with a ladder leading to a destination unknown.

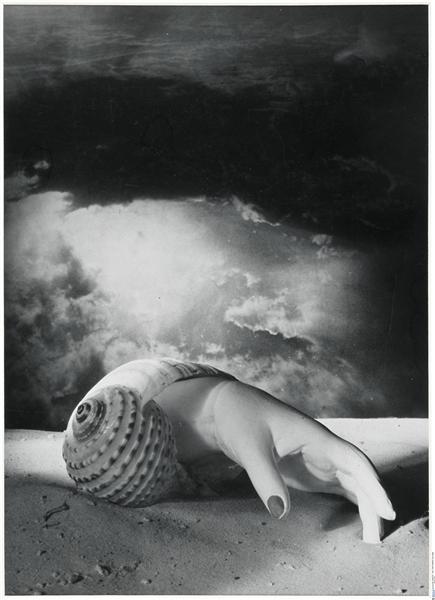

Dora Maar’s 1934 photo of a woman’s hand emerging from a shell in the sand against the backdrop of a cloudy sky is another excellent example of the Surrealist image:

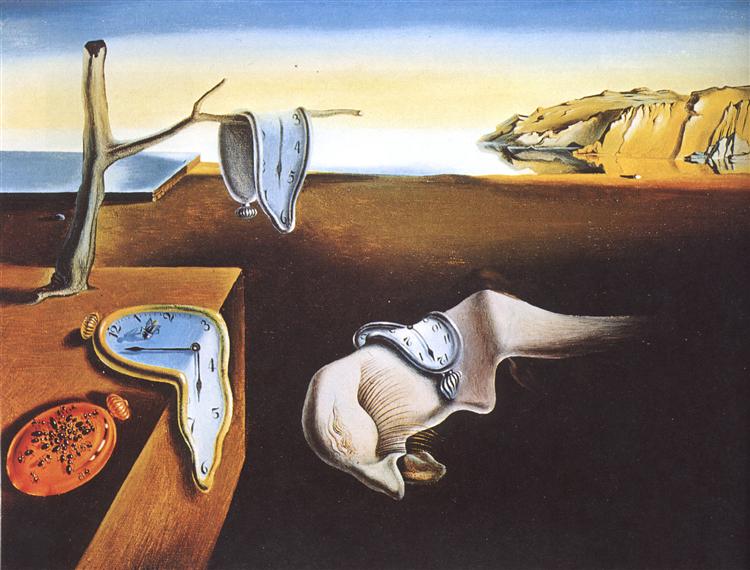

To elicit these unlikely juxtapositions many Surrealists employed techniques culled from the avant-garde, in particular collage, and devised new ones, such as frottage and fumage, while other artists including Richard Oelze and Salvador Dali brought the unconscious to vivid life through realistic modes, including photography, contrasting dreamlike content with precise detail, as in Dali’s “Persistence of Memory” (1931), a painting that hung in Loy’s apartment before shipment to New York.

The Surrealist Movement’s treatment and depictions of Women

Despite Breton’s dedication to a “perfect freedom” (This Quarter 22), the early Surrealist movement like Dada was male-dominated and entrenched in late nineteenth-century patriarchal attitudes towards women, and Breton’s homophobia was well-known.7

Whitney Chadwick points out that although women artists participated in Surrealist exhibitions, they remained on the margins of Surrealism’s official ranks: “Almost without exception, women artists viewed themselves as having functioned independently of Breton’s inner circle and the shaping of Surrealist doctrine.[ …] Their involvement was defined by personal relationships, networks of friends and lovers, not by active participation in an inner circle dominated by Breton’s presence” (11, 55). As was the case with Loy, Chadwick points out that “Their photographs are missing from formal Surrealist group portraits taken as late as 1934, but they appear frequently in informal snapshots of group activities” (Chadwick 9).

Loy’s affiliations with the Futurists in Florence and Dadaists in New York, her status as widow of Arthur Cravan, and her reputation as an artist and growing reputation as a poet, facilitated her entry into Surrealist circles in Paris. Her role as the Paris agent for Julien Levy’s Gallery in New York from 1931 to 1936 would give her a measure of influence over the trans-Atlantic migration of Surrealism. In her own writing and visual art of the Paris era and subsequently in New York, Loy adapts and transforms Surrealist ideas and techniques, cultivating a position of interested yet critical, feminist detachment. Although she played an important role in the Parisian “surreal scene,” Loy is missing from most Surrealist histories and exhibitions, and until recently was omitted from studies of women and Surrealism.8

While women artists like Loy remained on the margins of the movement, woman’s figurative role was central to Surrealism: representations of women, erotic desire, and the female body provided the material for much male Surrealist work. Breton idealized women as muse, as romantic ideal, and as a child-like medium to irrational or unconscious states, and conversely as “sorceress, erotic object, and femme fatale” (12). Chadwick points out that “In each of these roles she exists to complement and complete the male creative cycle” (13).

Breton’s semi-autobiographical novel Nadja (1928) is a case in point. Breton ‘finds’ Nadja in the streets of Paris, due to chance and erotic attraction, and chronicles their subsequent daily interactions. He describes her ‘free genius’ (111) as that of one ‘who enjoyed being nowhere but in the streets, the only region of valid experience for her, in the street, accessible to interrogation from any human being launched upon some great chimera, or (why not admit it) the one who sometimes fell, since, after all, others had felt authorized to speak to her, has been able [sic] to see in her only the most wretched of women, and the least protected?’ (113). Although Breton recalls Nadja telling him about the violence inflicted on her by men in the streets, and acknowledges that her poverty has caused her homelessness (142), when Nadja ultimately ends up institutionalized due to mental illness (136), Breton does nothing to help: what has happened to the woman herself (and the gendered and economic inequality that has contributed to her situation) is not his concern. Rather, Nadja’s importance lies in her role as a muse and embodiment of Surrealist ideals of urban wandering, “free genius”, and madness, enabling Breton to explore the self-directed question, ‘Who am I?’ (11).

The irrational qualities Nadja appears to embody are ultimately contained by Breton’s aesthetic use of them. Amelia Jones astutely observes “the tendency within Surrealism to rationalize in its own fashion — by orienting its explorations toward the ultimate recontainment of femininity, flux, homosexuality, and other kinds of dangerous flows that intrigued the surrealists but which they could not bear to allow to remain unbounded” (Irrational Modernism 252). This “recontainment” was often enacted through violence: as Linda Kinnahan argues, “visual and literary Surrealism centralized the image of the female body as a terrain for violence, borne of desire and anxiety and manifest through myriad images of women’s bodies penetrated, bound, mutilated, gagged, or ominously manipulated” (Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography 89). Bataille’s split from Breton and establishment of the magazine Documents furthered an explicit engagement with violence, masochism/sadomasochism, the gothic and perverse, in pointed contrast to Breton’s romanticism.

As Lucy Flint writes of Alberto Giacometti’s works created between 1930 and 1933, “The aggressiveness with which the human figure is treated in these fantasies of brutal erotic assault graphically conveys the content. The female, seen in horror and longing as both victim and victimizer of male sexuality, is often a crustacean or insectlike form. Woman with Her Throat Cut is a particularly vicious image: the body is splayed open, disemboweled, arched in a paroxysm of sex and death.”

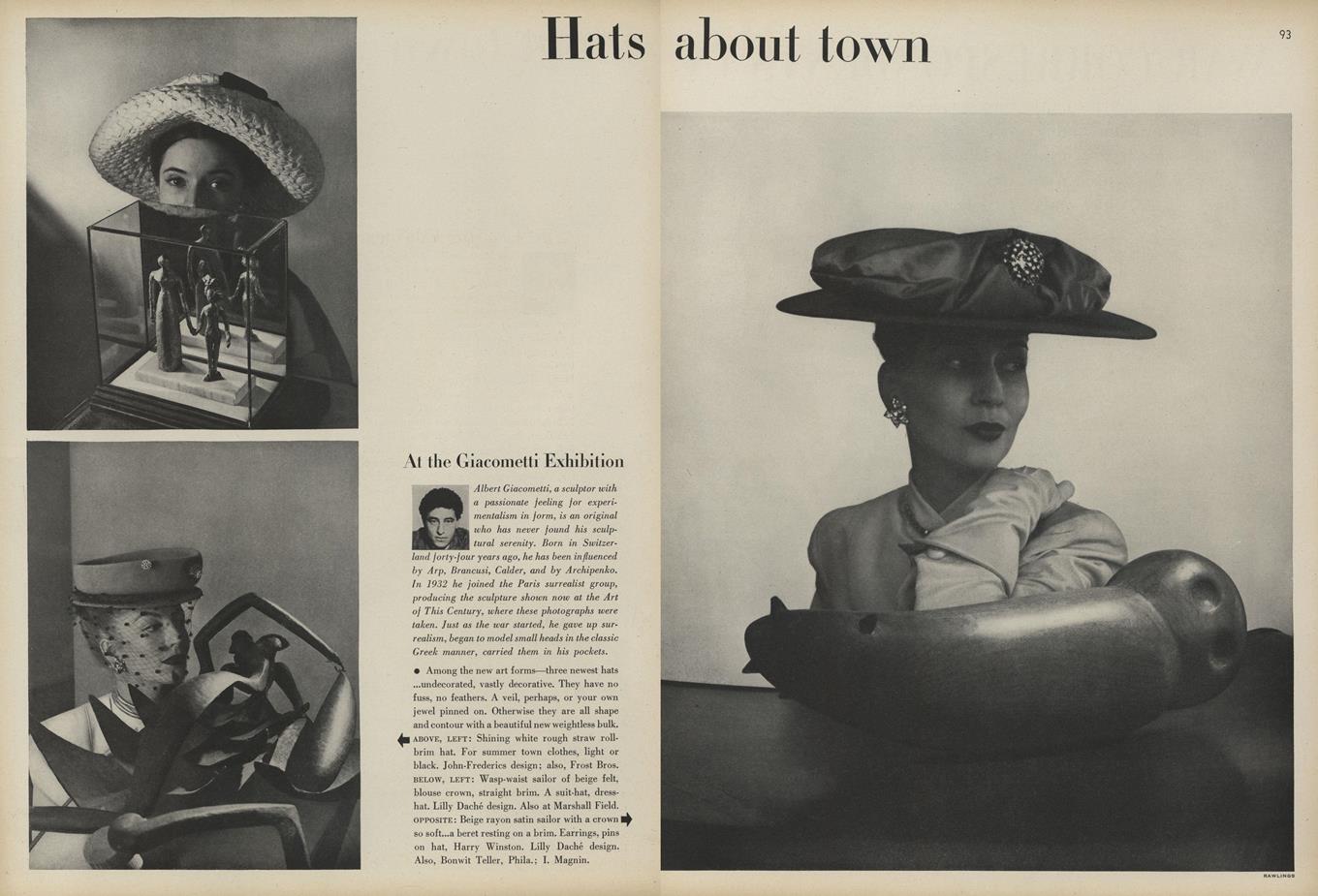

This April 1, 1945 Vogue feature, “Hats About Town, at the Giacometti Exhibition” (p. 92-93) was photographed at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery. The photograph of “Woman With Her Throat Cut” counters Giacometti’s abstract presentation of woman by including a female model, but visually positions the model’s head above a blade-like vertabrae emerging from the sculpture, to suggest a deep cut to the model’s throat. Echoing Giacometti’s violence to the female body to draw attention to the woman’s Lilly Dache hat advertised in the accompanying text, the Vogue photo suggests how fashion could echo and amplify the avant-garde’s objectification of the female body. On the other hand, the female model with her arched right eyebrow can be understood as a spectator staring back at Marinetti’s sculpture with a look of cool, critical detachment, and in their writing, artwork, and fashion designs, women would indeed engage critically with Surrealism as spectators and artists (See “Surrealist Objects, Fashion, Design” and Linda Kinnahan’s StoryMap “Mina Loy’s Fashion Designs”).

Women and the Surrealist Movement

Loy was no fan of André Breton. Julien Levy asked Loy to keep in touch with Breton, who wanted to publish Cravan’s surviving manuscripts (Burke 380); they would appear with Loy’s permission in VVV (no. 1 June 1942; no. 203 March 1943). Loy presents an unflattering portrait of Breton as “Moto” in her novel Insel:

It’s funny how people who get mixed up with black magic do suddenly look like death’s heads — they will grin and there is nothing but a skull peering at you, at once it’s all over — but you remember […] Often they look like goat’s. While Moto has the expression of an outrageous ram, his wife the re-animated mummy of an Egyptian sorceress. In fact, they are very, in their fantastic ways, expressive of their art, which after all takes on such shapes as would seethe from a cauldron overcast by some wizard’s tortuous will (Insel 1991, 21-22 ).

Loy objected to the “black magic” as well as the sexism and misogyny of the Surrealist movement, yet she and many other women were nevertheless inspired by Surrealism (Rosemont xxx, xlviii; Chadwick 7). In a 1931 letter, Loy wrote to her daughter and son-in-law Julien and Joella Levy that Surrealism was the only art movement that “could be wholly satisfactory” (quoted in Fort and Arcq, In Wonderland). Loy engaged Parisian Surrealism during the 1920s and early 30s, but would continue to consider, respond to, and transform Surrealism in New York (1937-1953), particularly as it intersected with fashion, documentary photography, and the art of Joseph Cornell.

So what did Surrealism offer to women artists and writers such as Mina Loy? As Penelope Rosemont argues, although the early Surrealist movement was male-dominated and many male surrealists were not feminists, they were nevertheless “the irreconcilable enemies of feminism’s enemies, and thus in many ways could be considered feminism’s allies. They concentrated their attacks on the apparatus of patriarchal oppression: God, church, state, family, capital, fatherland, and the military” (xliv). In this way, Surrealism offered a “sympathetic milieu” (Chadwick 11) to a “group of women who dared to renounce the conventions of their upbringing, who attempted to find some consonance between their ideas and their lives, and who embarked on the difficult path to artistic maturity at a time when few role models existed for women in the visual arts and there was little encouragement for women to establish professional identities for themselves” (Chadwick 9).

For Loy, the Surrealist interest in psychology, sexuality, and the irrational, unconscious, and spiritual dimensions of experience opened up a means of exploring the gendered forces structuring everyday life and the artistic imagination. More generally, the Surrealist dedication to an absolute freedom was capacious enough that it enabled artists and poets marginalized due to gender, sexual orientation, race, and class to adapt and transform it, and its history over the course of the twentieth century is one of increasing inclusiveness, as it traveled and influenced other, related movements in the U.S., Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Egypt, and Japan. From the outset, both Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and René Crevel defined Surrealism as a revolutionary spirit which they distinguished from its status as a movement controlled by Breton, a distinction which would prove particularly important not only to disaffected French Dadaists and Surrealists, but to marginalized artists including women like Loy who resisted any formal alliance with the movement.

Some women strongly identified as Surrealist, but others like Loy refused to do so, often due to the movement’s treatment of women, and ambivalence about affiliations with male-dominated avant-garde movements more generally (Chadwick 66). If we take a perspective broader than that of Bretonian Surrealism’s official roster and histories, then, from the 1920s forward we can track many women who were “associated with Surrealism” (Chadwick 10): they participated in Surrealist exhibitions, contributed to Surrealist periodicals or began their own, and/or engaged with Surrealist ideas and techniques in their own work (10). In 1920s and 1930s Paris this group variously included Leonor Fini, Valentine Hugo, Jacqueline Lamba, Dora Maar, Lee Miller, Valentine Penrose, Alice Rahon, Remedios Varo, Elsa Schiaparelli, Simone Yoyotte, Suzanne Césaire, Nusch Eluard, Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar, Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning, Germaine Dulac, Ithell Colquhoun, Peggy Guggenheim, Nancy Cunard, Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, Elizabeth Bishop, and Berenice Abbott, among others.

In their hands Surrealism became something new, what Rachel Blau Du Plessis has termed in relation to the Surrealist-inspired poet Barbara Guest a “fair realism” (Blue Studios 9, 180, 183). Loy, too, coined her own terms for her adaptations of the unconscious, Surrealism, and the surreal: she refers to “subconscious archives” (“O Hell”), “subvisual resources / in the uncolor of the unknown” (“Ephemerid”), the “irreal” (Insel), “galleries of the increate” (Insel), and “sub-realism” (“Phenomenon in American Art”). Particularly intriguing is the subtle claim by Loy and other women that their adaptations enabled a truer, freer Surrealism to emerge, that Surrealist ideals were most fully realized by those of the “En Dehors Garde,” positioned outside or on the margins of the Surrealist movement.

Negrophilia, Négritude, Afro-Surrealism

Just as the Parisian Surrealist movement was shaped by late nineteenth-century patriarchal attitudes towards women, it was also shaped by the history of European imperialism and colonialism. The Surrealist movement has a compex relationship to this history, opposing European imperialism and colonialism as part of its revolutionary poetics, and yet relying on stereotypes of non-white races as exotic and primitive others, stereotypes central to the Parisian avant-garde’s primitivism and Negrophilia.

As Petrine Archer-Straw writes, Negrophilia “means a love for black culture. In the 1920s, the term was used positively by the Parisian avant-garde to affirm their defiant love of the negro […] the word was meant to be provocative and challenging to bourgeois values” (9). Archer-Straw chronicles how “black forms were appropriated, adapted and vulgarized by whites” in “Advertisements, painting, sculpture, photography, popular music, dance and theatre, literature, journalism, furniture design, fashion and objets d’art” (9).

In the 1920s Negrophilia “reinforced negative stereotypes of blacks, especially in respect to primitivism,” a representational practice “created to be oppositional to or to complement the Western rational ‘I'” in its emphasis on sexuality, savagery, and deviance (Archer-traw 10-11). Surrealists explored primitivist representations of the racial other as an antidote to the rationalism of Western culture. As Archer-Straw argues, “The reality of the black man and the mystery of the land he represented became fertile psychological landscapes in which the white man could create and satisfy his desires. The line of demarcation between the real and the unreal became increasingly blurred. For Europeans, Africa and the black man were framed in notions of high adventure, savagery, fear, peril and death” (13). For the group centered on the ethnographic journal Documents founded by Georges Bataille after his split from Breton in 1929, “The negrophilia they advocated was far more transgressive than popular sentiment allowed. They went beyond a frivolous aestheticising towards a ‘hard primitivism’ involving an interest in sexual deviance, fetishism, magic, ritual practices and cannibalism as a way of critiquing and transgressing the norms of European society” (Archer-Straw 135).

While many Surrealists reinforced racist stereotypes of the primitive other, at the same time the Surrealist Movement opposed imperialism and colonialism, and Surrealism was unique among the historical avant-gardes in its appeal to and critical transformation by artists and writers marginalized due to race. As Franklin Rosemont and Robin Kelley point out in Black, Brown & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora, although people of color have been excluded from histories of Surrealism, writers and visual artists of color from the Caribbean, the U.S., Mexico, South America, Africa, Egypt, and Japan participated in Surrealist activities and contributed art and writing to Surrealist books and journals, exhibitions, and anthologies. Kelley and Rosemont argue that

“Surrealism’s solid grounding in poetry—in the practice of poetry as a way of life and, indeed, a social force—is directly related to its openly revolutionary position, and that in turn is directly related to the crucial but rarely acknowledged fact that Surrealism is the only major modern cultural movement of European origin in which men and women of African descent have long participated as equals, and in considerable numbers” (6).

Jean-Claude Michel writes that the Surrealists “held the belief that poetry was a kind of magical and primitive weapon capable of changing the world as well as mankind’s way of life” (Black Surrealists 3); as such, poetry became “eminently revolutionary” and for Black Surrealists, helped to generate “the vision of a New World order” (2).

Surrealism’s revolutionary poetics gained specific force through the movement’s anti-colonial, anti-imperialist politics and its complex affiliation with Marxism. Kelley and Rosemont emphasize Surrealism’s anti-colonialist stance, and note the Surrealist support for “the revolt of And el-Krim and the Rif tribespeople of Morocco in the summer of 1925” (9).9 Michael Richardson notes that the Surrealists opposed the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris, creating a counter-exhibition “The Truth about the Colonies,” and they published an anti-colonialist tract “Murderous Humanitarianism” in Nancy Cunard’s 1934 Negro: An Anthology, which was also signed by two writers from Martinique, Jules Monnerot and Pierre Yoyotte (Refusal of the Shadow 4).

Thus alongside the history of the avant-garde’s Negrophilia in the 1920s and early 1930s, it’s important to trace the anti-imperialist stance of the Surrealist movement, as well as the development of the Négritude movement by Francophone Caribbean writers in Paris. As defined by Bertrade Ngo-Ngijol Banoum:

“Négritude is a cultural movement launched in 1930s Paris by French-speaking black graduate students from France’s colonies in Africa and the Caribbean territories. These black intellectuals converged around issues of race identity and black internationalist initiatives to combat French imperialism. They found solidarity in their common ideal of affirming pride in their shared black identity and African heritage, and reclaiming African self-determination, self–reliance, and self–respect. The Négritude movement signaled an awakening of race consciousness for blacks in Africa and the African Diaspora.”

Surrealism was part of the backdrop for the articulation of Négritude, but the extent of its influence is debated. In 1932 a group of Martinician students in Paris published one issue of a journal called Légitime défense, whose title alludes to a book by Breton (Richardson, Refusal 4). Michael Richardson argues that “the Légitime défense group did function as a genuine collective, quite separate from the French Surrealist Group but informed by the environment of surrealism and receiving the encouragement of the surrealists. The focus of Légitime défense was the anti-colonial struggle, set in a surrealist and Marxist framework” (Refusal 5).

However, René Menil in his 1978 Introduction to Légitime défense emphasizes that “the discourse of Légitime défense is not a discourse of Négritude. Where Négritude affirms the priority of the cultural struggle over the political struggle and the priority of ‘black values’ over social contradictions, Légitime défense was, on the contrary, principally alert to the anti-imperialist struggle which roused colonial peoples against both the Western and its own bourgeoisie, situating political action in the Marxist framework of social transformation without conceiving the development of ‘black values’ other than within such political conflict” (“Introduction,” in Richardson, Refusal 38).

The connection between Parisian Surrealism and the development of Négritude is complex; as Brent Edwards argues, these intellectual traditions mark a “complex field of influence and debate, in which surrealism is only one term, and a hotly contested one at that” (Practice of Diaspora 193). 10 What’s clear, however, is that in early 1930s Paris a dialogue between Francophone Caribbean writers and Surrealism was initiated that would shape the development of Surrealism in the coming decades, helping to shift its center away from Europe and contributing to Afro-Surrealism.

Afro-Surrealism

As scholars have explored how non-white artists critically engaged and transformed Surrealism, a key concept has emerged: Afro-Surrealism. Offering a counter-history of Surrealism, Afro-Surrealism demonstrates the kind of critical revision that we also undertake on this platform through the concept of the “En Dehors Garde” as a counter-history and revisioning of the historical avant-garde.

As Jonathan Eburne argues, Afro-Surrealism is an anthologizing, belated neologism, naming a set of practices and mapping a genealogy rather than designating those who joined a group or movement; Afro-Surrealism comprehends rather than follows European Surrealism and encompasses artists variously associated with the Harlem Renaissance, Négritude, Pan-Africanism, Afro-Futurism, the Black Arts Movement, and the Chicago Surrealist group (ISSS). Eburne emphasizes several scholarly works as central to the development of Afro-Surrealism. Amiri Baraka coined the term in his essay “Henry Dumas: Afro-Surreal Expressionist” published in a special Henry Dumas issue of Black American Literature Forum (22.2) (Summer 1988) 164-166, in which Baraka introduced Dumas’ 1974 Ark Of Bones and Other Stories. Also important to the development of the term is the Fall 2013 issue of Black Camera (5.1) on Afro-Surrealist film, and Rosemont and Kelley’s anthology Black, Brown, and Beige, discussed above. In addition, D. Scot Miller published an influential “AfroSurreal Manifesto” in the San Francisco Bay Guardian (May 20, 2009).

The concept of Afro-Surrealism helps make visible a history that was present all along but overlooked or marginalized in histories of the Surrealist movement, and the work of women writers and artists has proven central to this Afro-Surrealist counter-history. For instance scholarship on Jane and Paulette Nardal has demonstrated their central role in the development of Négritude, through their writings, periodicals (Paulette was one of the founders and editors of La Revue du monde noir), and Parisian salon. Brent Edwards argues that “What is especially important and particularly unique about the circle around the Nardal sisters is that it cleared space for a kind of feminist practice that otherwise was not possible in the midst of the vogue nègre in Paris” (Practice of Diaspora 158). Bertrade Ngo-Ngijol Banoum points out that Paulette Nardal served as a “primary cultural intermediary between the Anglophone Harlem Renaissance writers and the Francophone students from Africa and the Caribbean, three of whom would later become the founders of the Négritude movement: Aimé Césaire from Martinique, Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal, and Léon-Gontran Damas from French Guiana.” Simone Yoyotte has received attention as the only woman who contributed to the journal Légitime défense (Rosemont, Surrealist Women 66-67).

Martinician writer Suzanne Roussy Césaire’s essays, which appeared in the journal Tropiques (1941-1945) which she co-founded and edited with her husband Aimé Césaire and René Ménil, are central to the articulation of Négritude and a Martinician Surrealism; Penelope Rosemont calls her “one of surrealism’s most brilliant and daringly original theorists” (126).11

Suzanne Césaire’s 1943 essay “Surrealism and Us” which originally appeared in Tropiques (no. 8-9, 1943) eloquently articulates the promise of Surrealism, clarifying why women from backgrounds different than that of Breton sought to adapt and transform Surrealism to their particular circumstances. Césaire argued that “Surrealism’s activity today extends throughout the entire world, and it remains livelier and bolder than ever. […] Surrealism lives! And it is young, ardent, and revolutionary” (Rosemont, Surrealism and Women 133-134). But she pointed out that as Surrealism migrated from Paris it “has evolved — or, rather, blossomed,” adding that

When Breton created surrealism, the most urgent task was to free the mind from the shackles of absurd logic and of so-called reason. But in 1943, when freedom herself is threatened throughout the world, surrealism, which has never for one instant ceased to remain in the service of the largest and most thoroughgoing human emancipation, can now be summed up completely in one single, magic word: freedom. (Rosemont, Surrealism and Women 134)

Summarizing what Surrealism can offer “Millions of black hands,” she wrote:

Our surrealism will supply this rising people with a punch from its very depths. Our surrealism will enable us to finally transcend the sordid antinomies of the present: whites/Blacks, Europeans/Africans, civilized/savages — at last rediscovering the magic power of the mahoulis, drawn directly from living sources. Colonial idiocy will be purified in the welder’s blue flame. We shall recover our value as metal, our cutting edge of steel, our unprecedented communions.

Surrealism, tightrope of our hope. (Rosemont, Women and Surrealism, 136-7)

(To read more on this topic, explore “Loy, Surrealism, & Race”).

←Back to Surreal Scene: Paris, 1923-36- On what Dickran Tashjian has called “the difficult problem of plotting the subtle and mercurial transformation of Dada into Surrealism” (Skyscraper 14) see his discussion in Skyscraper and Boatload of Madmen; on the reception of this transformation in the U.S. little magazines see Rosenbaum, “Exquisite Corpse.”

- The Baroness was called “the first American Dada” and “mother of Dada” (Gammel, Baroness 4). “Women energetically shaped their own forms of dada” (14), Gammel writes, and the Baroness’s “play with body-centered art” (4) made her “America’s first performance artist” (7).

- Roger Conover points out that Arthur Cravan, who introduced himself in the boxing ring as the “Poet and Boxer Arthur Cravan,” embodied the co-existence of opposing qualities: “In his masculine comportment was a feminine negotiation of opposites, a willing of reluctant inner brides. In the boxing ring, the figure thrusting and receiving was vulnerable and volatile, subtle and brute, respectful and taunting. In his stanzas, masculinity and femininity, anxiety and repose, eloquence and slang, sentiment and sexuality were likewise the diametric poles that generated a voltaic cell of poetic power” (4 Dada Suicides 23). See also Roger Conover’s discussion of Cravan’s importance to the pre-history of Dada and relationship with Loy in “Introduction” LLB82, pp. vlvii-lxi.

- This document can be found in a folder titled “Correspondence, Mina Loy to Joella Bayer and Assorted Others, ca. 1934-1949, 1960.” A note in pencil at the top of the page says “M re AC c. 1936, Colossus?”

- See Roger Conover’s discussion of the publication and reception of Loy’s “Love Songs” (1915) and of the completed sequence “Songs to Joannes” (1917) in LLB96, pp. 188-194.

- Breton controlled the membership of the Surrealist movement, publicly breaking with or expelling those who disagreed with his ideas, including Crevel and Aragon (in Crevel’s case for his homosexuality and in Aragon’s for political differences regarding Surrealism’s communist commitments) (Nadeau; Matthews 154). Ribemont-Dessaignes commented in the Little Review in 1926, “They don’t agree any more about Surrealism than they used to about Dadaism. The same thick swamp subsists. Who is surrealist, who is not? They know it only at the Central Office – where everybody is it” (41).

- On women and Surrealism, see in particular Chadwick; Caws, Kuenzli, and Raaberg; Fort and Arcq; Lusty; Hubert; P. Rosemont.

- An important exception here is Tere Arcq and Ilene Susan Fort’s In Wonderland, which includes a full-page reproduction of Mina Loy’s painting Surreal Scene (1930) as well as a brief biography and treatment of her engagement with Surrealism. In addition, both Sarah Hayden in Curious Disciplines: Mina Loy and Avant-Garde Artisthood, and Linda Kinnahan in Mina Loy, Twentieth-Century Photography, and Contemporary Women Poets, offer in-depth analyses of Loy’s relation to the Surrealist movement and her critical adaptations of Surrealism.

- “In a July 15 statement they declared their solidarity with the Riffians and affirmed “the right of peoples, of all peoples, of whatever race” to self-determination. This statement was followed a few weeks later by the collective tract “Revolution now and Forever!”—the Surrealist Group’s first important political declaration, in which members elaborated not only their attitude toward the war in North Africa, but also their critique of Western civilization and their growing awareness of themselves as traitors to the white race and avowed enemies of Eurocentrism…” (Black, Brown & Beige 9-10).

- Edwards argues that Légitime défense “demands to be read in a complex field of debate among black periodicals of the period, especially in its conjunction with La Revue du monde noir” (195). He takes issue with Michael Richardson’s emphasis on the influence of Bretonian Surrealism over that of the Harlem Renaissance, exemplified by Claude McKay’s “Banjo” published in Légitime défense (196-8).

- See also Jennifer M. Wilks’ chapter, “Surrealist Dreams, Martinician Realities: The Negritude of Suzanne Cesaire” in Race, Gender, and Comparative Black Modernism (LSU Press, 2008).