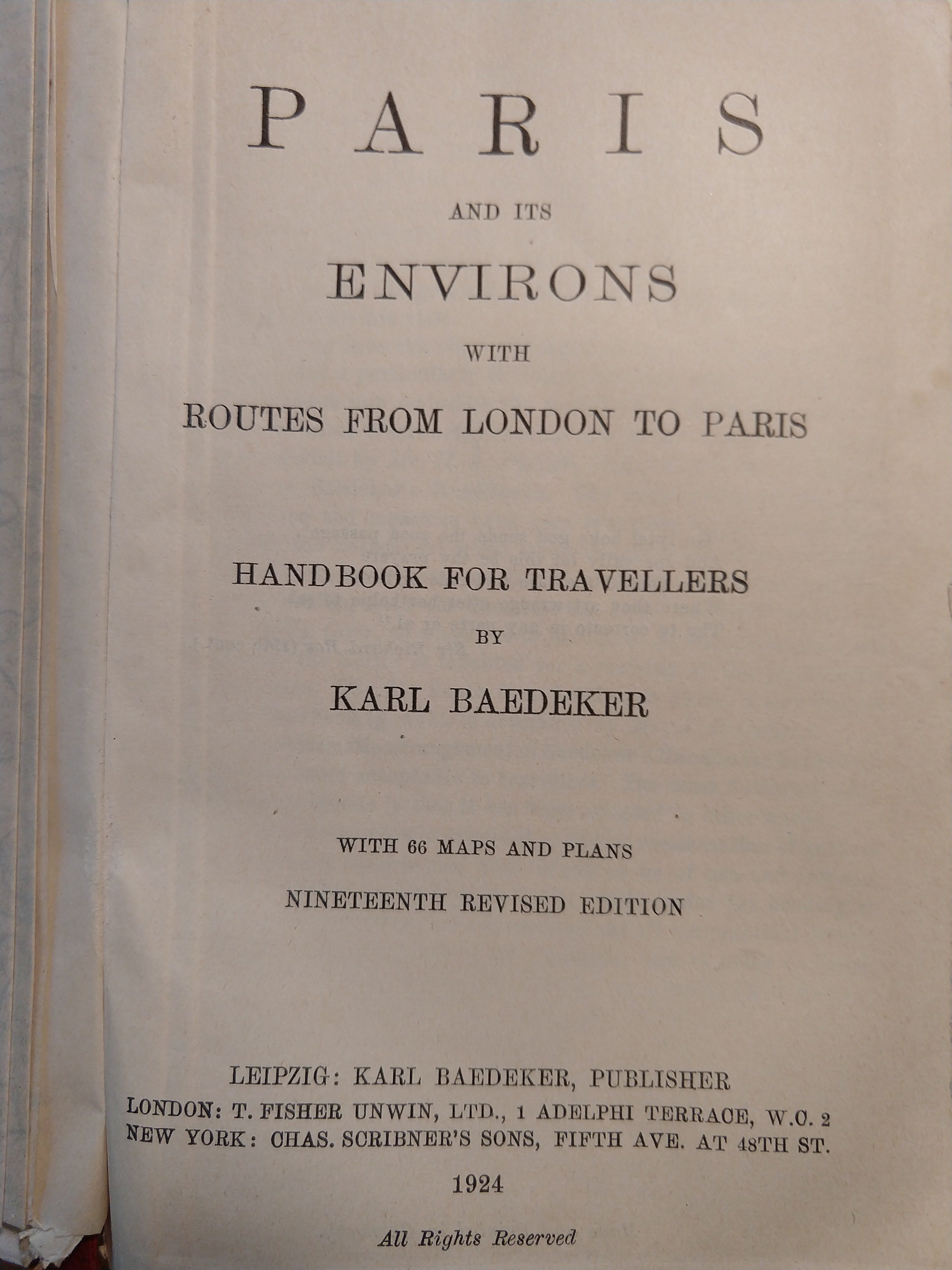

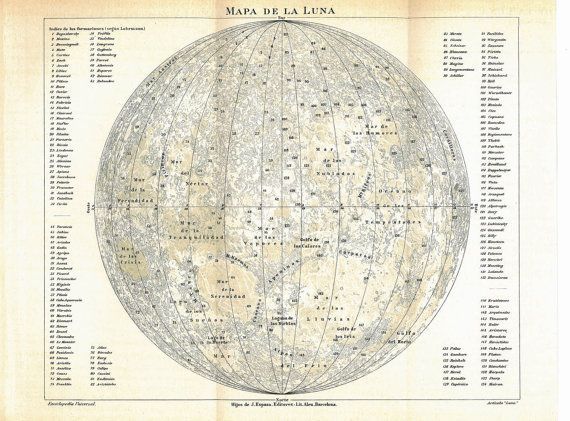

In 1923 Lunar Baedecker (sic), Loy’s first collection of poems, was published by Robert McAlmon’s Contact Publishing Company in Dijon. Divided into two sections, Poems 1921-1922 and Poems 1914-1915, the collection provided an aesthetic and geographical roadmap to the artists, places, and works of modernism that had mattered most to her on her journey. The title poem “Lunar Baedeker” describes an otherwordly city:

A silver Lucifer

serves

cocaine in cornucopiaTo some somnambulists

of adolescent thighs

draped

in satirical draperiesPeris in livery

prepare

Lethe

for posthumous parvenues (LLB96 81)

Inspired by Karl Baedeker’s famous guides, Loy’s poetic map guides the reader through an “irreal” city (LB96 134) — which she variously depicts as a city on the moon, a city of the dead, a city viewed in black and white as if on film — whose urban scenes seem to reflect, distorted and transformed, New York, Florence, Berlin, Paris.

The publication of Lunar Baedecker in 1923 marked for Loy the end of an era of trans-Atlantic travel and the beginning of an era centered chiefly in Paris. After her years in Florence (1906-1916), travel bracketed Loy’s two stays in New York (1916-17, 1920-21): in the years 1918-1920, Loy married Arthur Cravan in Mexico (January 1918), and following Cravan’s disappearance at sea, Loy travelled to Valparaiso, Chile and on to Buenos Aires in Fall 2018. In March 1919 Loy left Argentina for England (Surrey) where she gave birth to Fabienne in early April 1919, then travelled in June 1919 to Geneva to meet Cravan’s family, and on to Florence to see her children Giles and Joella, before returning to New York in March 1920. In the years 1921-1923, Loy followed a similar peripatetic path: she left New York for Florence in summer 1921, visiting Paris that summer and again in November 1921 (Burke 307, 310). In Spring 1922 Loy travelled to Vienna, where she met and drew Freud, and then moved to Berlin, where she lived until the start of 1923. In Spring 1923 Loy settled in Paris, where she would remain until 1936.

This would be Loy’s second extended stay in Paris: her first, from 1903-1906, was defined by her experience as an art student, her marriage to Stephen Haweis, and the birth and death of her daughter Oda. But much had changed for Loy in the interim. During this second stay, Loy would raise her daughters Joella and Fabienne, open her lampshade shop, celebrate Joella’s marriage to Julien Levy, and work as the Paris representative for Levy’s New York gallery. She would create surrealist objects and paintings, write poetry, essays, and autobiographical fiction, and begin a surrealist novel.

Loy signaled that Lunar Baedecker marked the end of an era but also the beginning of a new one through the collection’s reverse chronology. In choosing to begin the book with her most recent poems (1921-1922) written during her travels in New York-Florence-Paris-Vienna-Berlin, followed by the poems she wrote in Florence while associated with Futurist circles (1914-15), Loy presented a genealogy of her poetic career.

The poems of 1921-22 map Loy’s modernist constellation, with many poems occasioned by particular artists or works important to her own aesthetics, including James Joyce’s Ulysses, Brancusi’s sculpture “Bird in Flight,” Wyndham Lewis’s drawing “Starry Sky,” Stein’s experimental prose, and Poe’s essay “Philosophy of Composition.” Her poems draw on her travels in the U.S., England, France, Germany, and Italy. Reading forward in Lunar Baedecker one also reads backwards in Loy’s geographic and aesthetic trajectory, with the second section centered on Loy’s engagement with Italian Futurism and her relationships with Marinetti and Papini. Tellingly, Lunar Baedecker ends with Loy’s poem “Parturition” (1914), shaped by her feminist critique of Futurism, Catholicism, and late Victorian understandings of birth and motherhood (See “Firenze is a Woman”). This poem can be read as a distinctly feminist stance on modernism as the “birth of the new”: ending her first collection with this poem, Loy positioned her poetic career as one inaugurated by a feminist transformation of the modernist avant-garde.

This transformation centered on Loy’s desire to chart her own individual path rather than align with a particular artistic group, movement, or tradition.1 Loy’s Lunar Baedecker not only maps the temporal, geographic, and aesthetic relationships that defined her career, but breaks new aesthetic ground, ground that Loy figures as the landscape of the moon. Loy’s geography of the moon is both fantastical and real, tied to the cities she navigated and to her imaginative vision; this geographical and imaginative dislocation allowed her to critically engage the gendered scenes and tropes of the avant-garde, while illuminating new possibilities, mapping a little-seen space we might connect to that of the en dehors garde. Present at the scenes of avant-garde activity yet often rendered marginal or invisible, en dehors garde artists and writers devised new ways to navigate and represent this liminal position.

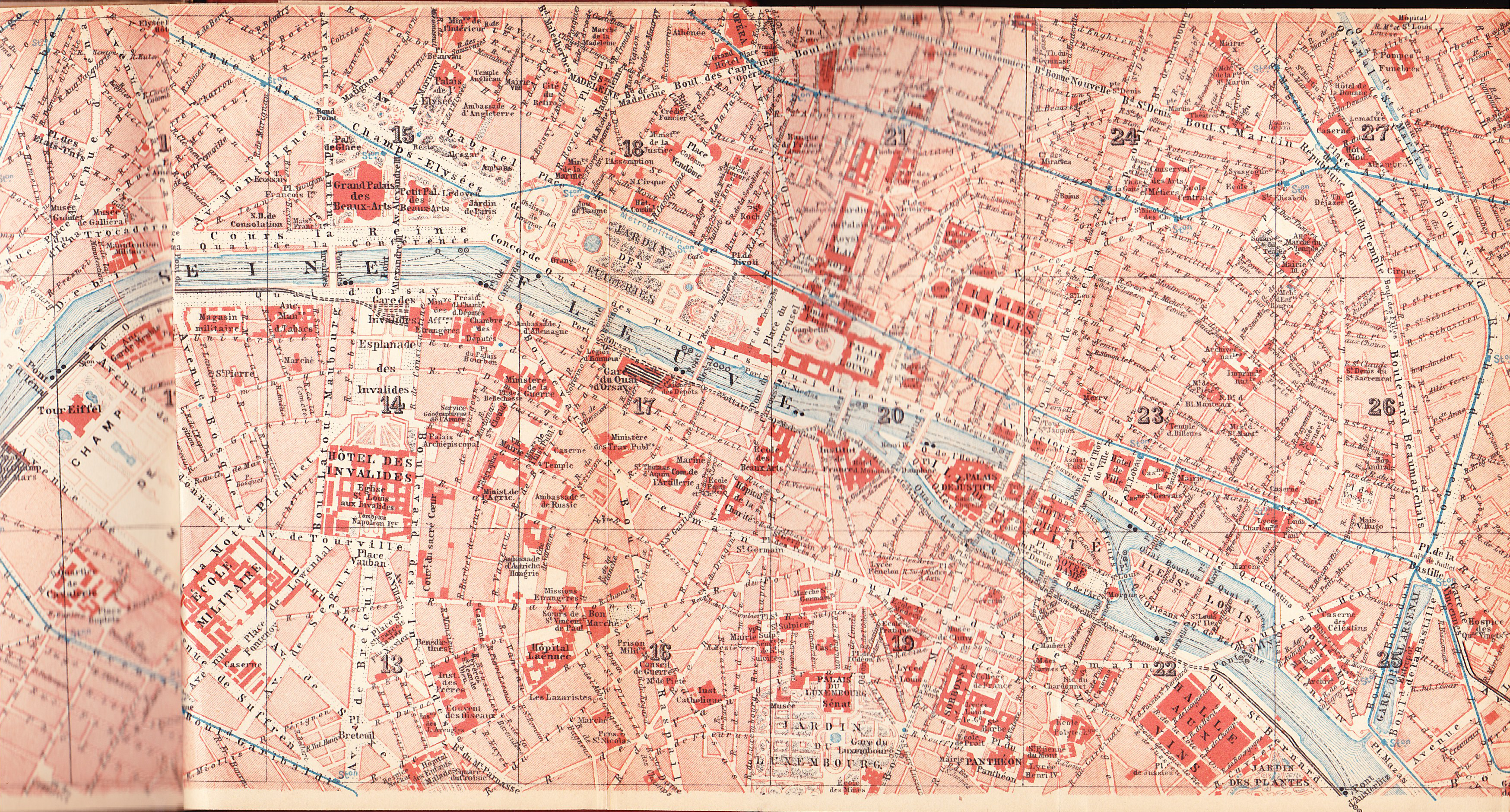

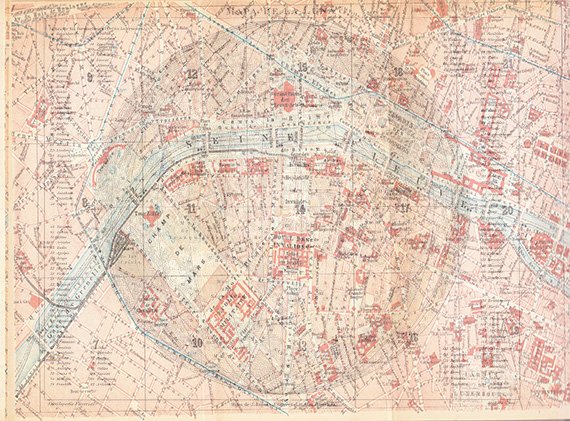

Lunar Baedecker moves fluidly between the experiments of the European avant-garde and those of the Anglo-American modernists, and in Paris Loy moved fluidly between these groups as well. Most writers and artists lived, worked and socialized on the Left Bank, and as the Paris map created by Courtney Mullis and Indy Recker demonstrates, this was largely true for Loy, with the exception of her lampshade shop which was located on the right bank.

The visualization of Loy’s social and artistic network based on the biographies of modernist figures written by students at Davidson College, Duquesne University, and the University of Georgia, illuminates Loy’s centrality to a number of overlapping circles in Paris, described by Loy biographer Carolyn Burke as “a group comprised of British and American writers, their French counterparts, and assorted Dadaists or Surrealists” (328).

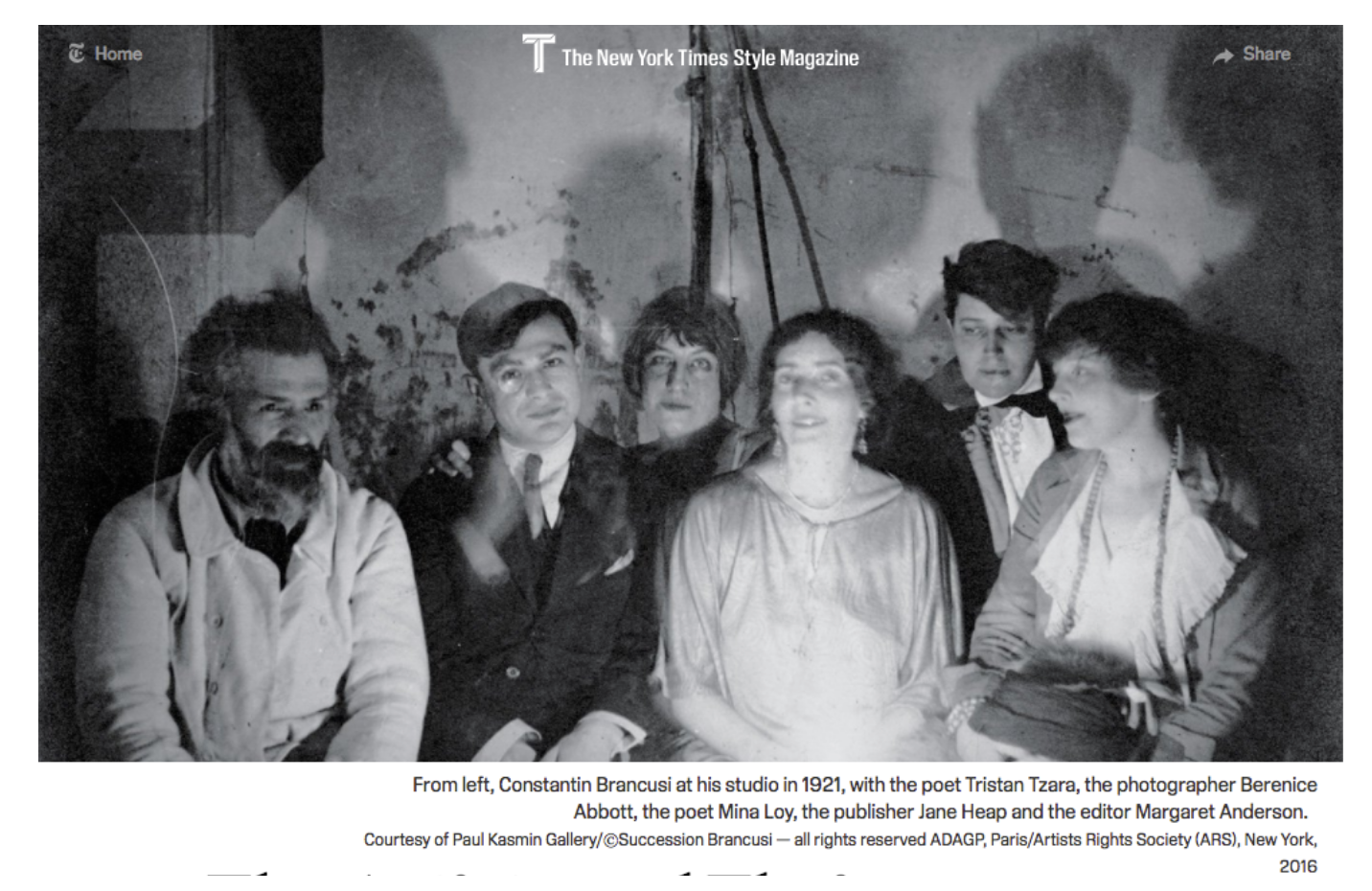

This group was memorably captured in two photos from the time:

Loy is seated at the center of this 1921 photo taken in Brancusi’s studio, literally bridging European (Constantin Brancusi, Tristan Tzara) and American avant-gardes (photographer Berenice Abbott; Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson, editors of the Little Review).

In this 1923 photo Loy is seated at the front of a group outside the Jockey, including the Little Review editors (Jane Heap, Margaret Anderson, Ezra Pound) and figures associated with Paris Dada (Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, Jean Cocteau): kneeling in her fashionable coat and hat, and turning her head to smile at Man Ray who appears to be taking a photo of the photographer, her vibrant, active role is clear.

Loy’s position in these photos suggests that she was adept at navigating and bridging different modernist groups in Paris, a role for which she was well-suited given her extensive travel in Europe and the Americas, and an aesthetic orientation defined by absorbing elements from different artists, groups, and movements, while remaining indebted to none.

Women such as Loy challenged and remade the modernist landscape in 1920s and 1930s Paris. The following sections trace her engagements with Paris Dada, Surrealism, and Anglo-American modernism, and in doing so, consider how Loy transforms the definition and boundaries of the avant-garde, to encompass the related yet less visible landscape of the en dehors garde. In 1920s and early 30s Paris, the “irreal” would burgeon into the fantastical forms explored by the Surrealist movement. If Loy’s poetic tour of the lunar landscape shaded in the unseen territory of the en dehors garde c. 1923, that map would take on new meaning and grow in complexity as Loy navigated the scenes of Parisian Surrealism in the 1920s and early 30s (for further discussion of the poem “Lunar Baedeker” see “Criticism of Freud & Eros Obsolete” and “Return to New York”).

- Although Loy’s critical stance on the avant-garde was informed by feminist insights and beliefs, she never joined the Suffrage movement or any kind of feminist organization, and her “Feminist Manifesto” (1914) begins “The feminist movement as at present instituted is Inadequate” (LB96 153). Like Dora Marsden in her Egoist phase, Loy emphasized the development of the individual woman over her political action or affiliation.