Ilene Susan Fort connects the pink background in Loy’s 1930 painting Surreal Scene to Louis Aragon’s 1924 poem “Une vague de rêves” which states “There is a surrealist light: at the time of day when towns burst into flame it is the light that falls on the salmon pink display of silk stockings […] There is a surrealist light in the eyes of every woman” (In Wonderland 34).

That “surrealist light” would become literal for Loy, who in 1926 applied herself to creating functional yet beautiful objects: lamps. As an artist and poet who needed to make a living, Loy first began making and selling lampshades in New York in 1917 (Burke 224), and also exhibited a painting (now lost) titled, “Making Lampshades,” at the Society of Independent Artists exhibition (Burke 227). Carolyn Burke refers to Loy’s first lampshade business as “moderately successful” (340), and in Paris Loy returned to the lamp and lampshade business but pursued it on a larger scale.

Peggy Guggenheim, who had helped sell Loy’s Jaded Blossoms objects in New York in 1925 (Burke 338-9), initially financed Loy’s lampshade shop.1 The shop was located in a wealthy shopping district at 52 Rue de Colisée, a street connecting the Champs-Elysées and Rue du Faubourg St.-Honoré (Burke 341). Along with her daughter Joella Loy prepared and furnished the shop, rubbing lead dust into the walls to conceal the cracked enamel (Burke 341). The shop opened in September 1926 and was so successful that Loy hired assistants for the shop and for a workshop that she opened in Montparnasse (near Avenue du Maine) (Burke 342-4, 365).

From the outset the financial partnership was fraught, as Guggenheim purchased the shop but required Loy to invest money up front for the costs of preparing the shop and lamps, and was not timely about reimbursement. Guggenheim also exerted her control, initially using the shop to display — in addition to Loy’s lamps — lingerie, slippers, and her husband Laurence Vail’s paintings (341-2). Tristan Tzara wrote the catalog introduction for the exhibition of Vail’s paintings (Burke 342): that the lampshade shop also served as the “Galeries Mina Loy” was in keeping with the overlap between art and commerce in Loy’s career and in her engagement with the “scenes” of Surrealism.

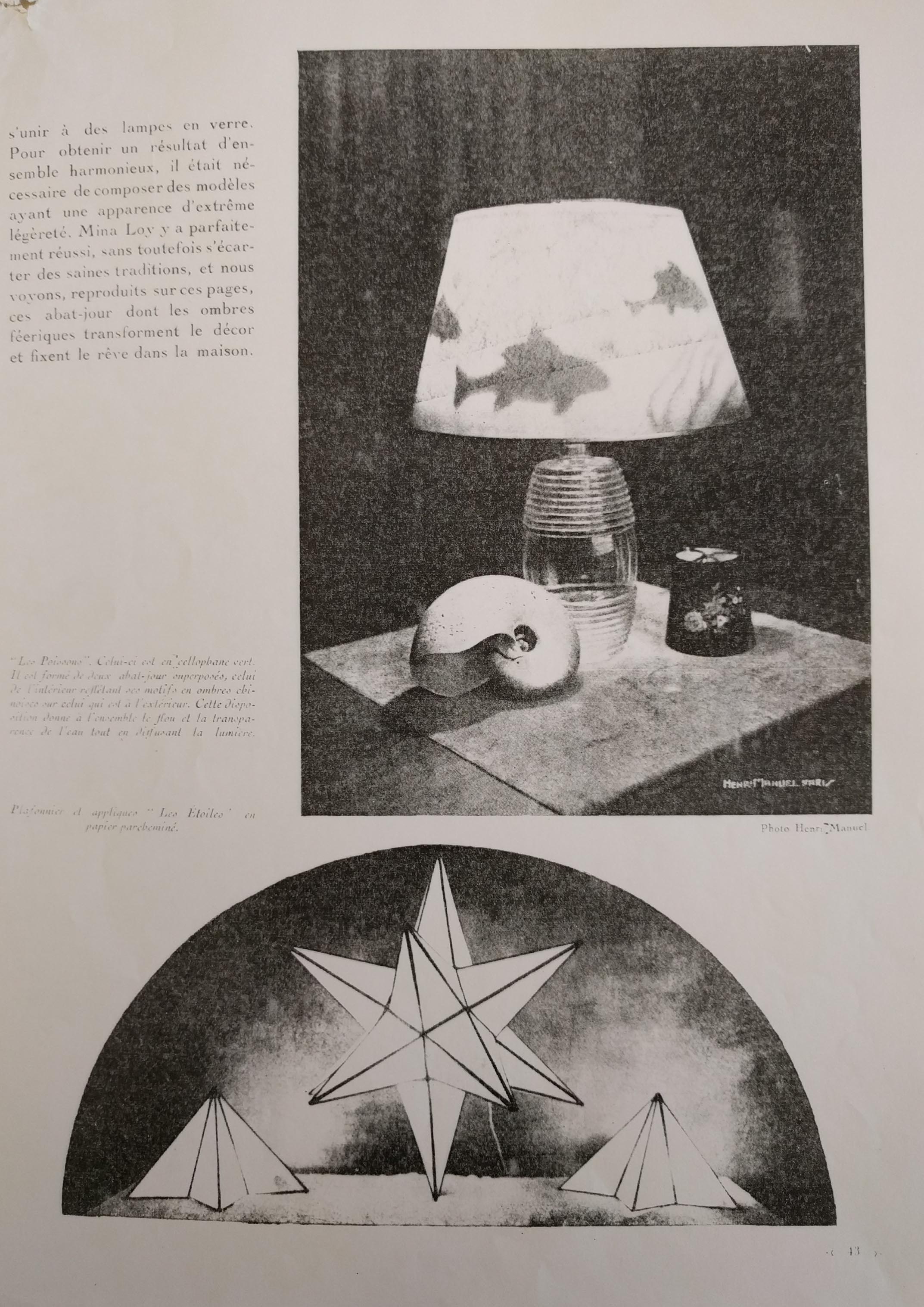

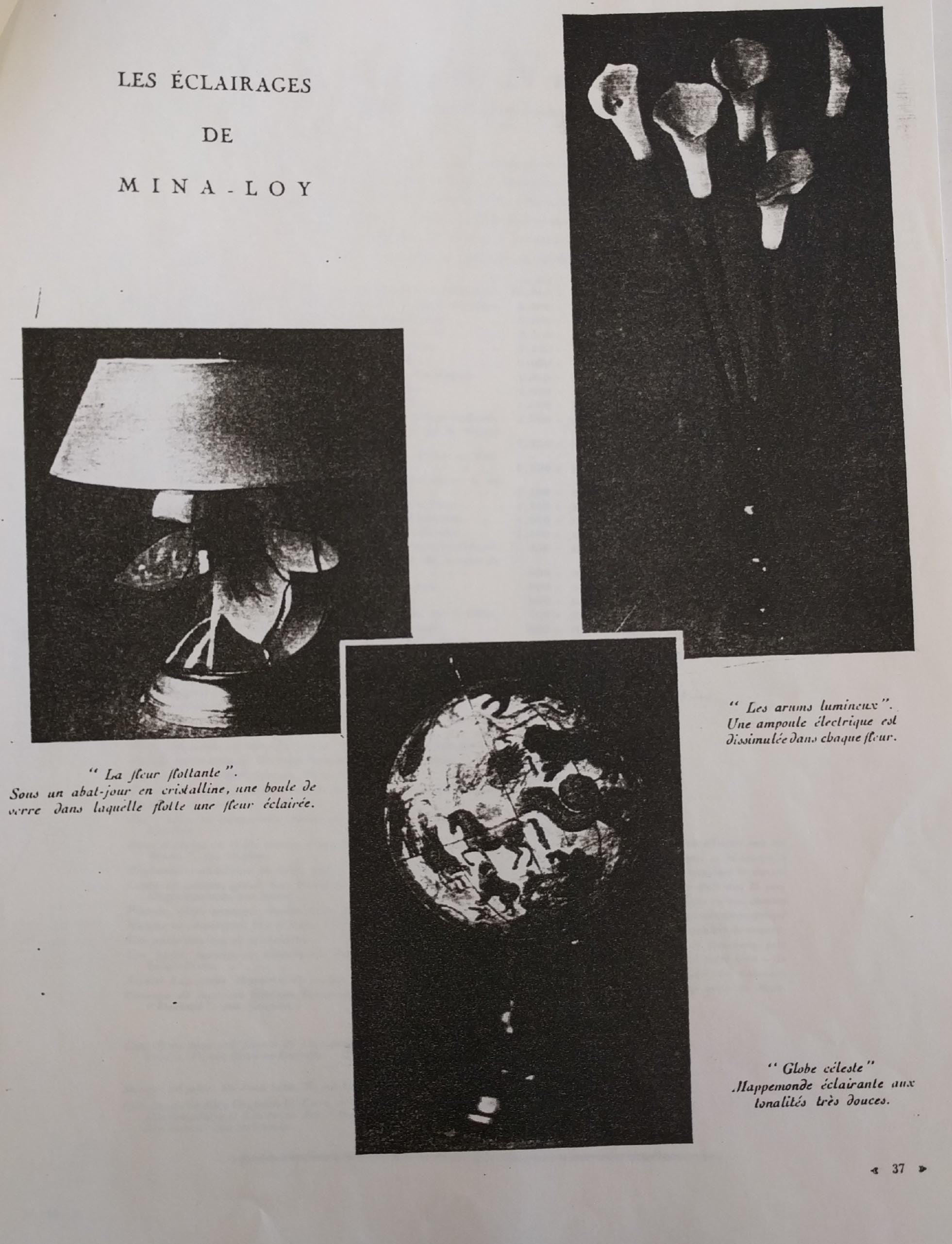

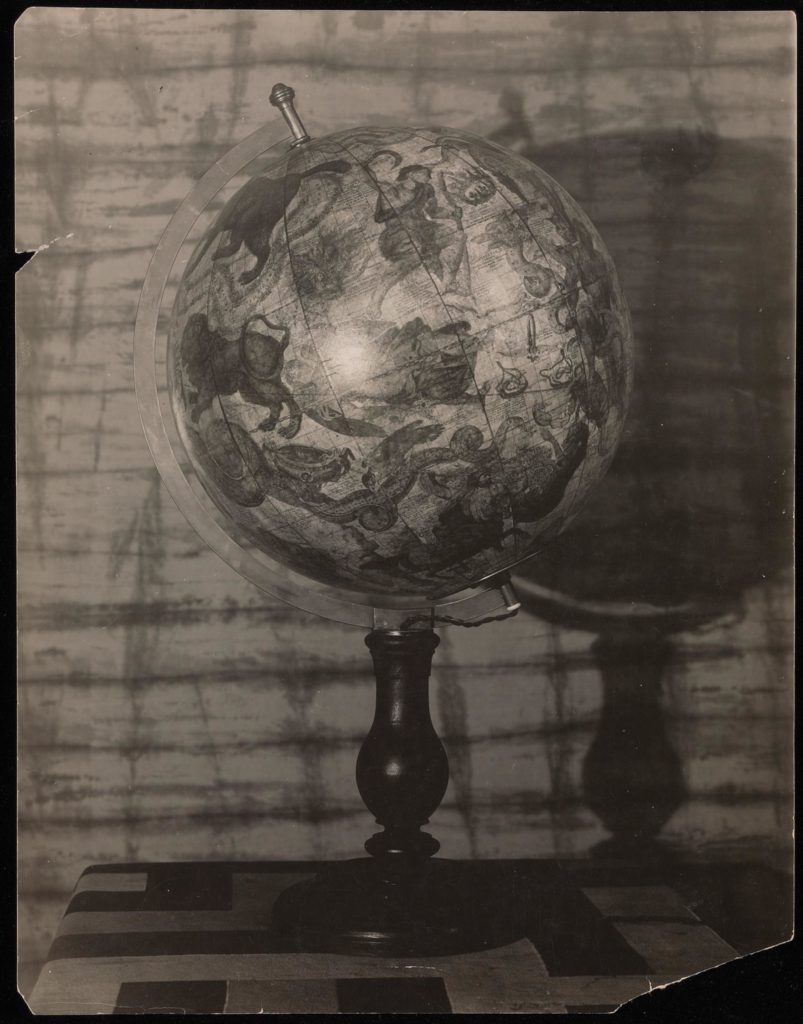

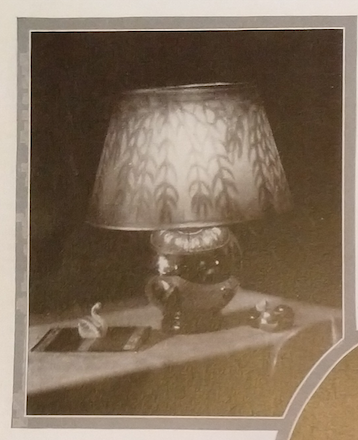

Loy designed the lamps herself, using antique bottles from her bottle collection as the lamp base (many of which she had found in the flea market), and created the lampshades by hand from a variety of opaque and translucent papers including cellophane, and from synthetic materials including rhodoid and Crystal Lux (Burke 340-342). Loy’s lampshade designs were inspired by the oceans, celestial maps, and the natural world: those inspired by the sea included a sailing ship, waves, and a fish, while her illuminated celestial and world globes and star sconces “seemed to have materialized from the pages of Lunar Baedecker” (Burke 343). Loy’s water plant, water lily, calla lilies and swan lamps created a vision of a quiet garden pond.

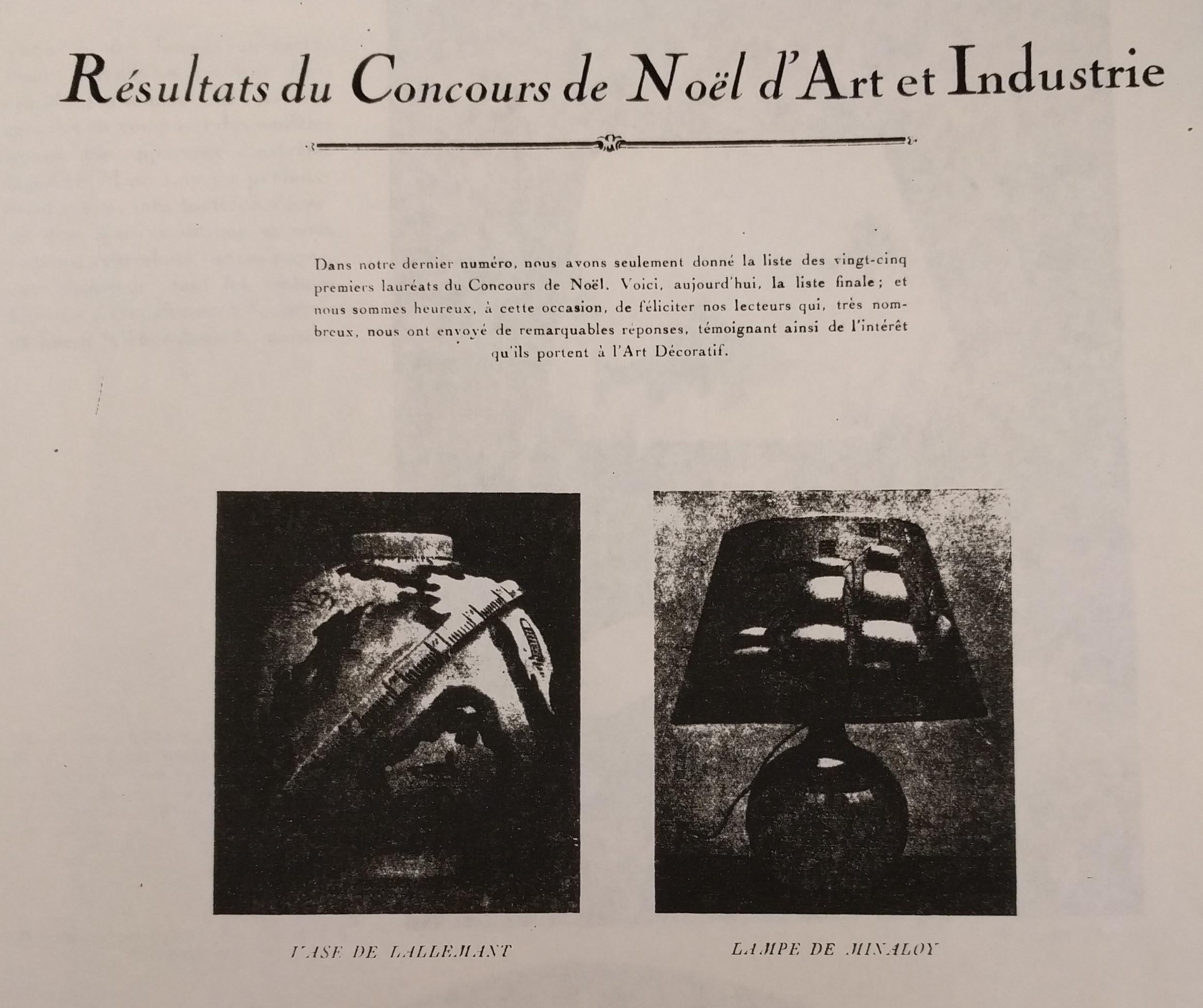

The lamps sold well: Loy advertised them as “L’Ombre féerique” (fairy shadows) in Art et Industrie (Art and Industry) magazine, and they were featured with photographs in both Art et Industrie (1927, 1928) and in Arts and Decoration magazine (1927) (Burke 343). The most popular design, an illuminated globe lamp, sold for 2,000 francs/100 dollars (Burke 365).

Several lamp photos are available through the Beinecke Library’s Digital Archive:

Carolyn Burke describes the lamps as a “streamlined version of Art Nouveau” (365), but Loy may have engaged Surrealist aesthetics in her designs, particularly if we consider the lamps as poetic conduits capable of transforming domestic interiors into aquatic or celestial environments through the generation of shadows and silhouettes.2 One critic admired the “lampshades whose fairylike shadows transform the decor and domesticate dreams” (Burke 343), while Arts and Decoration magazine commented of Loy’s “red fish” lampshade: “The effect of this lamp shade […] is as though the fish were swimming through the water in an aquarium, very clever and exceedingly life-like.”

Loy described the power of light to transform an apartment interior into just such an “aquarium” in her surrealist novel Insel: she wrote,

The world of the Lutetia had materialized. An infiltration of half-light softly bursting the dark, a thin cascade, the ferns dripping into a green gloom. Here, where dawn and noon and midnight were all so dim and Insel lay sensitive to clarity as a creature of the deep sea; the closely shuttered studio with its row of glass doors was a real replica of the irreal ‘aquarium’ (109-110).

Indeed the “ferns dripping into a green gloom” describe well one of Loy’s lampshades featured in Arts and Decoration magazine:

In her lamp designs built from antique bottles and other inexpensive materials Loy purchased at stores or in the flea market, Loy engages the Surrealist found object (See “Surrealist Objects, Fashion, Design”). Loy’s feminist commentary on the Surrealist found object emerges in an episode from Insel, in which Insel comments on a lampshade designed by Mrs. Jones that “It would surely be of the greatest interest to Freud” (166). Mrs. Jones replies:

“The still life that intrigued him was a pattern of a ‘detail’ to be strewn about the surface of clear lamp shades. Through equidistant holes punched in a crystalline square, I had carefully urged in extension, a still celluloid coil of the color that Schiaparelli has since called shocking pink. Made to be worn round pigeon’s ankles for identification, I had picked it up in the Bon Marché.

Out of this harmless even pretty object an ignorant bully had constructed for me, according to his own conceptions, a libido threaded with some viciousness impossible to construe.

I was astounded” (166-7).

In essays written in Paris Loy expressed contempt for Freud’s understanding of the female libido: Mrs. Jones is incensed by Insel who blithely echoes Freud while ignoring the innovative thrift and economic necessity legible in the lampshade design.

Two French companies, Lanvin and France Danube, as well as Macy’s and Wanamaker’s in New York, became interested in Loy’s flower-lamp designs (Burke 365). Loy’s lamp designs were successful enough that many cheaper knock-offs began to appear, and in Spring 1928 Loy filed lawsuits to prevent the use of her designs, to no avail (Burke 366). In 1928 Julien Levy’s father Edgar Levy loaned Mina Loy 10,000 dollars to buy out Peggy Guggenheim (Burke 366). Loy’s frustrations with copies of her designs continued to mount however, prompting her to put the shop up for sale in Autumn 1929; she sold the shop in March 1930 for 75,000 francs (Burke 370).

Jessica Burstein points out that “Anxiety about copying had led her to copyright her lamp designs, and later it would cause her to record the origin of her inventions by a variety of means ranging from the official to the inventive” (191). She sums up Loy’s dilemma, as an artist who prized originality but depended on the sale of her work, thus: “The marketplace, riddled with copies, was both threat and promise for Loy” (196).

Given the fragility of the materials Loy used to make her lamps, Carolyn Burke notes that “few, if any […] have survived” (343). Hopefully a few examples of existing lamps will surface.

Contemporary photos & reviews of the lamps were published in the following magazines.

Art et Industrie:

January 1927 p. 42-43 “Les Abat-Jours de Mina Loy”: p. 42 La Galère, les Vagues; p. 43, Les Poissons et Les Étoiles

March 1927 p. 53, “Résultats du Concours du Noel d’Art et Industrie”

February 1928 p. 37, “Les Eclairages de Mina Loy”: La Fleur Flottante; Globe Céleste; Les Arums Lumineux

May 1928 p. 59 L’Ombre féerique

Arts and Decoration:

July 1927, p. 56 “Prize Lamp Shades from Nina Loy [sic] of Paris”

Explore the Davidson student project “Illuminating Loy: Designs, Inventions, and Commerce” under New Frequencies.

- In addition to Carolyn Burke’s discussion of Loy’s lamp shop, see Jessica Burstein’s discussion in Cold Modernism, p. 187-189.

- In discussing Loy as a designer across media, Jessica Burstein coins the term “domestica” so as “to emphasize the household elements in Loy, crossed as they are with a rigid eroticism that makes strange the recognizable circuits of the everyday” (152).” This insight can be applied to many of Loy’s lamps, which denaturalize “the recognizable circuits of the everyday.”